The admiral stood victorious, his battered vessel rocking gently with the changing of tide that had served him so well. With his sword stained crimson and his face blackened with soot, he observed with elation the seascape of carnage laid out before him. He’d performed a miracle this day, and the exhausted yet heartened crews of his tiny fleet knew it. More importantly, the enemy knew it.

In 1545 Yi Sun-sin (Yee Soon-shin) was born into a family which had served as military officers for generations. Yi passed the military service examination in 1576, though he had to take it twice, having fallen from his horse in a freak accident during his first attempt. Yet this inauspicious beginning launched an incredible career.

Assigned to a succession of low-level positions in both the army and navy, he first gained the court’s attention for actions facing the Jurchen in 1583. Through guile and solid military tactics, Yi proved remarkable amongst his peers. Chief State Councilor Yu Song-nyong, a childhood friend, emerged as a strong advocate near the throne, ensuring future assignments would increasingly recognize Yi’s potential. Their friendship would also save the kingdom.

Assigned as commander of the Left Jeolla Navy, based at Yeosu on the southern coast, Yi arrived in 1591 to find a small fleet of 24 pannokson and 15 hyeupson at anchor in the bay.

Studious and diligent, Yi set to work learning all he could about naval command and warfare. Pouring through the archives he discovered the 1413 A.D. plans for a simple turtle ship and, after consultations with a local shipbuilder, ordered construction to begin.

Both Yi and Councilor Yu were convinced that war with Japan was coming. Yi strengthened his fleet, trained the men, and made logistical arrangements to support wartime operations.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

The Japanese Prepare For War

Japan’s invasions of Korea spanned 1592-1598 A.D. and reflected the ambition and desire of one man, Japan’s Toyotomi Hideyoshi. Unable to claim the title of shogun due to his lowly birth, he nonetheless ruled Japan as first Kampaku (Regent) and then as Taiko (Retired Regent). Regardless of title, his rule was absolute. The conclusion of his campaign in 1590 brought Japan under his control, ending – or at least putting on hold –123 years of civil war.

Yet Hideyoshi had a problem. Japan had been fighting itself for so long that it teemed with an excess of warriors and warlike men. The samurai class was restless in a suddenly peaceful Japan. Local uprisings and internecine feuds plagued the empire. Hideyoshi needed an outlet for this military energy – especially for the troublesome clans from Kyushu, who proved his most combative subjects.

Across the sea to the West lay the Chinese Ming Empire. Haughty in its dealings with Japan, the Ming routinely treated Japanese emissaries with disdain, looking down on a culture that seemed to worship combat to the detriment of more filial pursuits. The long-standing Chinese prerequisite to kowtow before the emperor in order to conduct trade did not sit well with Japan’s martial leaders.

Trade was thus limited and piracy was rampant. Japanese marauders haunted the coasts of China and Korea, sometimes raiding deep inland in search of food and booty.

Between China and Japan lay Joseon Korea, at the time ruled by King Sonjo. A deeply Confucian state, Korea’s ties to Ming China were strong after the two joined forces to end Mongol domination of the region two centuries prior. This cooperation led to the longest period of Sino-Korean peace in their 2,000 years of shared history. The Joseon court had long realized the value of trade and played the part of China’s little brother to secure necessary economic benefits.

In preparation for the assault upon China, Hideyoshi demanded safe passage for his armies through Korea. This was something quite impossible for Sonjo. The king refused and immediately dispatched word to the Ming Emperor at Nanjing. The Japanese were coming.

The Invasion Begins

The division of 18,700 Japanese men that landed at Busan on May 23, 1592, was a veteran force, hardened by a lifetime of incessant warfare and bored by two years of peace. The samurai were deadly in close combat and also armed with Portuguese-derived arquebuses of superior quality to any firearms carried on the Asian Continent. Japan’s initial landing would be followed by 131,000 troops in seven divisions.

Joseon’s Army, in steady decline since the defeat of the Mongols, was almost the polar opposite of its opponent. Officers gained position by passing national examinations. Their soldiers were conscripts, raised only when needed and with a modicum of training and experience. What few professional warriors Korea maintained were mostly cavalry and deployed in the northeast facing the troublesome Jurchen.

An undercurrent of factionalism at odds with any rational attempt to accomplish military objectives undercut both sides in the conflict. On the Korean side, the court was split into “Easterners” and “Westerners” struggling for favor and position throughout the course of the war, sometimes with deleterious effects upon the actual fighting. For the Japanese, long-standing rivalries between many senior commanders complicated battlefield coordination. High-ranking samurai almost came to physical blows at least once.

Strengths and Weaknesses

It was only 694 kilometers from Busan to the Chinese border. Yet the problem with invading Korea was the peninsula’s difficult terrain. Steep mountains and fast-moving rivers constituted a defender’s paradise, defeating invaders even without help from a population stubbornly unwilling to live under foreign control.

Any invasion of Korea thus demanded more of the logistician than the tactician. Any incursion into China, presumably launched from a secure base in Korea, required supplies to be transported north across endless mountains or by sea around the southern and western coasts.

Realizing the difficulty in maintaining long lines of land communication, Hideyoshi favored the sea, and assembled 700 transports and 300 warships to make it work.

All was now in place for Asia’s first real naval war. Yet for all the apparent advantages the Japanese armies had over their Korean foes, the exact opposite was true when it came to their respective navies.

Hideyoshi had no full-time navy and the ships he ordered into service were owned by subordinates with fiefs on the coast, many of whom had been pirates.

In contrast, Korea, in response to constant piracy along its coasts, had long maintained a professional navy. Ships were designed from the keel up to operate in the shallow, rocky littorals which gird the Korean peninsula.

Japanese sea-going warships at this time were light and v-hulled, built for speed. Japan’s preferred tactic was to board enemy vessels and fight hand-to-hand. Narrow abeam, and top-heavy, the largest of their ships could only mount three to four cannons facing forward. Most of the samurai fleet, however, consisted of unarmed transports relying upon massed arquebus fire as the primary means of ranged weaponry.

Korea’s pannokson were flat-bottomed with a wide beam and expansive fighting deck. Each battleship mounted 20 or more cannons capable of delivering devastating, large caliber broadsides out to a thousand paces.

The centerpiece of every Korean fleet, pannokson were the capital ships of the navy, supported by smaller vessels called hyeupson, and fishing boats pressed into use as scouts.

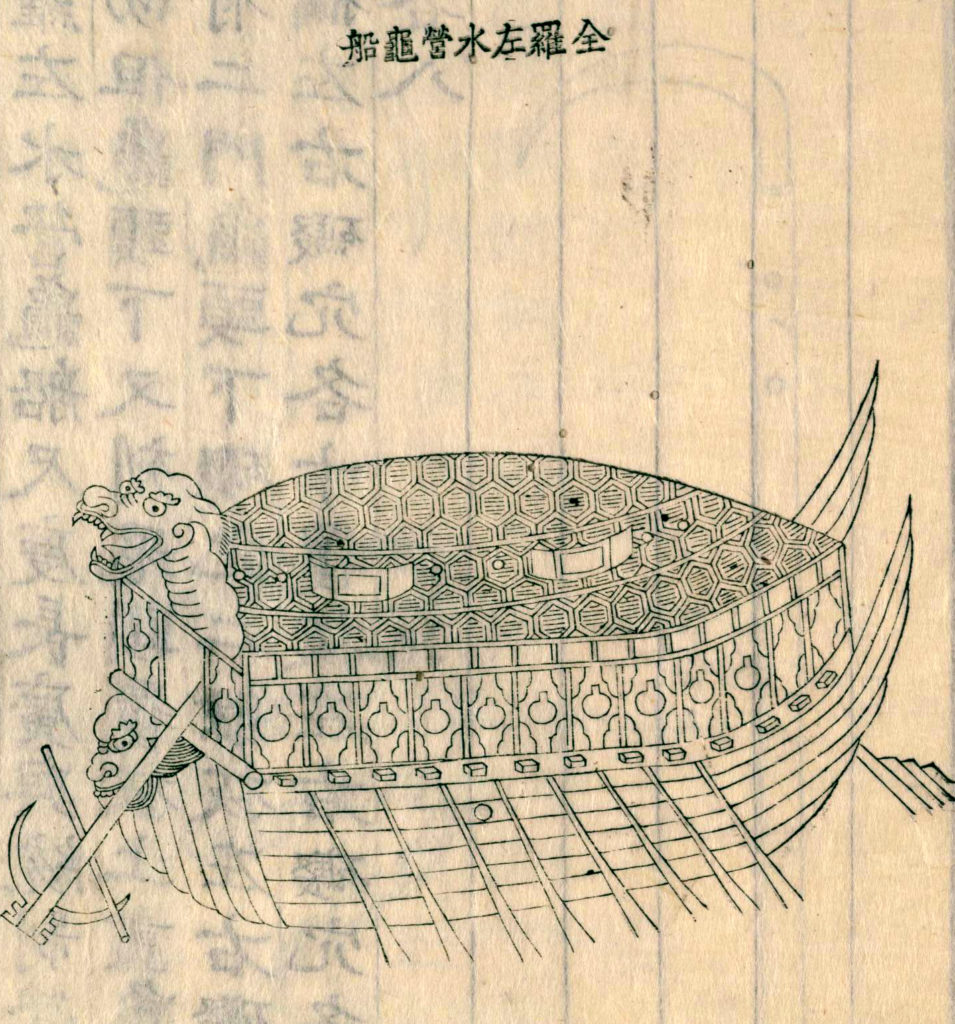

Admiral Yi also commissioned the construction of kobukson, the famous “Turtle Ships” that stunned his foes. Riding low in the water, the covered fighting deck of a “turtle ship” was sealed from inside and studded with iron spikes to discourage boarding.

Designed to ram the more fragile Japanese ships, these ships also carried an impressive complement of cannon. Yi’s first turtle ship was completed just in time for the war — a stroke of luck for the soon-to-be famous commander.

Yi Takes Action

Reports of the Japanese landing at Busan, and the fall of Dongnae Fortress to the north, reached the admiral within a few days. More disturbing news included the scuttling of both Left and Right fleets of the nearby Kyongsang Navy.

This represented an incredible lost opportunity as the vanguard Japanese commander, Konishi Yukinaga, tired of waiting for his warship escort, had rashly sailed to Busan with only unarmed transports. This Japanese force could easily have been slaughtered by the Kyongsang Navy’s combined 150 pannokson. Instead the two Korean admirals, Pak Hong, and Won Kyun, fearful of the enormous fleet filling the horizon, burned their vessels and deserted their posts. Won Kyun seemingly had a change of heart mid-way through the act and four of his pannokson escaped destruction.

In the rapidly evolving situation, Yi acted deliberately. He gathered maps, intelligence, and supplies, and received the court’s permission to sail beyond his assigned area of operations off Jeolla Province.

Coordinating with the commander of the Right Jeolla Navy, his intent was to combine their fleets, link up with Won, and commence combat operations against the invaders.

Won’s hysterical pleas to the court for assistance — hypocritically accusing Yi of cowardice in the face of the enemy — forced Yi’s hand. He was ordered to set sail before the Jeolla Navy was able to consolidate. After linking up with Won’s skulking remnant near Koje Island, Yi learned of a Japanese naval force raiding a local village.

When he sailed into Okp’o Harbor on June 16, 1592, Yi Sun-sin stepped into the spotlight of military history.

The First Korean Victory

Catching the enemy in the act of pillage, the Korean fleet formed a line of battle as the Japanese rushed to their ships or fled into the hills beyond the burning village.

Yi rallied his inexperienced crews and set to work destroying as many enemy vessels as possible with cannon fire. He reported to the court the destruction of 26 ships — the first Korean victory of the war and news that lifted the spirits of King Sonjo.

Over the next 24 hours, Yi attacked two more isolated Japanese forces and sunk an additional 20 vessels. The Koreans had thus far lost no ships and suffered only three casualties.

As the fleet rested from three battles in two days, terrible news arrived that Seoul had fallen to advancing Japanese armies. The king had escaped to the north.

Both admirals wept at the news. They agreed to withdraw to their bases, file official reports, and plan their next engagement. Another reason for Yi’s decision to return to Yeosu became clear when he launched sorties three weeks later. His turtle ship was ready for action.

Rampage Through the Japanese Fleet

Yi’s rampage through the Japanese fleet—including a daring raid on Busan itself, destroying 128 enemy vessels—continued through 1594 when a ceasefire was arranged by Korea’s Ming ally. Armies of samurai had reached Pyongyang and Korea’s northeastern border, but were forced to retreat south through attrition and the allied Ming-Joseon army.

By the time of the truce, Japan controlled only a string of fortifications along Korea’s southern coast. Most of these fortresses were isolated. Admiral Yi controlled the sea lanes and guerrillas roaming the hills, rendering logistical sustainability difficult.

Yi refused to stand idly by, however, while the invaders remained on Korean soil. In defiance of Ming envoys and Joseon officials, he maintained pressure on the “robbers” right up until large-scale military operations resumed in 1597.

However, when the samurai were again let off the leash, Yi was no longer at the head of the triumphant Korean navy – a stunning development with serious consequences.

The Admiral Is Betrayed

By 1597 Yi had been responsible for the destruction of over 352 Japanese ships. Japanese leadership realized something had to be done if success were to be achieved in a second invasion attempt.

Yukinaga set a trap. He passed word that Kato Kiyomasu, whom he hated, would soon return from Japan, and urged Yi to intercept the force as it transited. Yi, however, saw through the false report and refused to take the bait.

Scheming Korean court members seeking to undermine the Easterner Faction cited Yi’s “failure” to act and accused him of “disloyalty and disobedience.” These charges were presented them to King Sonjo who, incredibly, issued a warrant to arrest Korea’s savior.

Yi obediently left the combined fleet — by this time over 200 vessels including at least three turtle ships — in the incompetent hands of Won Kyun.

The hero was led in chains back to Seoul. There he was tried, found guilty, tortured, and demoted to the rank of private soldier. Sentenced to serve in General Kwon Yul’s army, Yi’s new commander felt sorry for all that had befallen the man. Kwon allowed him to fulfill his duties at home in Ansan, where he mourned the recent passing of his mother.

Disaster struck in Yi’s absence. Won led the fleet into another Japanese trap at Chilcheollyang. Everything about this battle indicates that Won had learned nothing while serving at the right hand of Yi. Despite his clear advantage in firepower, Won impetuously rushed to engage the enemy in “glorious” close combat. As a result, the Korean fleet was shattered. Only 12 pannokson and 120 soldiers escaped the slaughter.

Yi was still living in disgrace when a royal messenger arrived. The kingdom needed his help. Yi was officially reinstated him as commander of the combined fleet.

Victor of 18 battles during the first invasion, Yi took command of a demoralized force and less than half the ships that had been at his disposal than when the war began.

With his customary energy, he went to work, already receiving reports that the enemy intended to capitalize upon the presumed destruction of the Joseon Navy. All odds were in favor of the samurai, and it must have appeared to the Japanese that Hideyoshi’s plan would succeed.

Using Nature as an ally

The stage was now set for the most impressive of Yi’s battles, which transformed him from a hero into an unparalleled legend in the pantheon of Korean historical figures.

Yi laid a trap of his own at the volatile Myongyang Strait. He hoped that by using local knowledge of the environment and a personal display of courage that he could rebuild the confidence of the battered remnants of his once-strong navy.

A Japanese force of over 300 vessels, including at least 130 warships, sailed west toward the Jeolla coast. This armada would, by necessity, pass through Myongyang — a narrow strait where the tidal surge reaches 10 to 12 knots and, remarkably, changes direction every three hours. Yi possessed this information. Clearly his enemy did not. Buoyed by their recent victory, the Japanese rushed headlong to attack on sight.

Becoming trapped in the narrows, the invaders were unable to bring overwhelming force to bear against the small Korean force.

Understanding the timing of Myongyang’s tidal currents allowed Yi to control and pace the battle. He took advantage of the natural phenomenon to magnify cannon and ramming attacks upon his astonished foes.

By the end of a hard day’s fight, Yi had sunk 31 enemy vessels, once again without losing a single ship. The remainder of the Japanese force fled all the way to Busan, never again to challenge Yi’s control of Jeolla’s coastline.

Yi’s incredible victory at Myongyang single-handedly derailed the second invasion, forcing the immediate abandonment of the Japanese thrust toward Seoul and a return to their isolated coastal fortifications.

Yi’s Death in Combat

A large Chinese fleet reinforced Yi in July 1598 and the reinvigorated Korean Navy prowled the littoral, hunting any vessel bold enough to make the perilous run to the fortresses at Suncheon and Sacheon.

Yi would continue to harass Japanese supply lines, even participating in a coordinated sea-land attack on Suncheon Castle on October 19. Later the same month, however, word arrived that Toyotomi Hideyoshi had died. The war was over, and the invaders hastily negotiated a ceasefire to facilitate their withdrawal.

Unwilling to allow his enemy to depart unscathed, Yi instituted a naval blockade of Suncheon, preventing Yukinaga’s 15,000 men from making their escape. With Ming and Joseon forces controlling all land and sea approaches, the samurai were in a bind, yet rolled the dice once more, testing their luck against Yi’s tactical brilliance for the last time.

The Battle of Noryang on December 16, 1598, culminated in the sinking of over 200 Japanese vessels. However, it created enough of a diversion for Yukinaga and his men to escape. More importantly for Koreans, it also resulted in the death of Admiral Yi.

Yi fell in combat, while securing a tremendous military victory, quite literally chasing the enemy from his beloved homeland. The admiral’s death in his final battle kept him far from the postwar factional politics of the kind that had nearly ruined him — and the country — just one year prior.

An Enduring Legacy

Throughout his six-year naval command, Yi fought and won 23 battles, destroying over 780 Japanese ships without losing a single vessel of his own, an incredible military record by any account. His actions during the first invasion prevented Japanese seaborne supply, forcing an impossible overland route, and causing the vanguard samurai armies to wither on the vine. This frustrated not only the attempt to pacify the Korean countryside but left the invaders logistically incapable of invading China.

His timely passing neatly protected Yi Sun-sin’s legendary status — one he maintains to this day in memorials etched onto statues around modern Korea including one at Gwanghamun Plaza in Seoul, and another overlooking Busan Harbor.

Yi’s reputation for diligence, self-discipline, and unwavering devotion to duty — despite his government’s unjust persecution of him — have placed him above all others in the litany of Korean historical figures worthy of emulation.

For Yi, perhaps the greatest honor of all would be the reverence he instilled in the descendants of his enemies. When Adm. Togo was celebrated for his incredible victory over the Russians at Tsushima in 1905, an admirer compared him to admirals Horatio Nelson and Yi.

A naval hero himself, and descendant of Kyushu samurai, Togo responded, “It may be proper to compare me with Nelson, but not with Korea’s Yi Sun-sin, for he has no equal.”

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.