In 1615 Japanese warlord Tokugawa Ieyasu surveyed his last battlefield, the blood-soaked ground of Tennoji near Osaka. He’d seen much conflict across the width and breadth of the empire, but at age 72 his work was done. All

of Japan had been brought under consolidated military rule—his rule, a fact made clear to all when the emperor named him shogun, meaning roughly “barbarian-quelling generalissimo.”

Yet Ieyasu hadn’t reached this peak by himself. The foundation for a unified Japan had been laid by his peers Oda Nobunaga and Toyotomi Hideyoshi. That Ieyasu not only knew but also fought both against and alongside his predecessors makes the story of Japan’s bloody unification unique in the annals of military history.

Recommended for you

Nobunaga The Conqueror

Nobunaga was a minor daimyo (feudal lord) when he embarked on his own path to greatness. Born within the precincts of Nagoya in 1534, he wrested leadership of the Oda clan when his father died in 1551. Through a series of campaigns concluding in 1559 he established control of Owari Province, the heavily fortified, rice-rich base of operations for all that followed.

Gauging the Oda clan weakened by the effort, the neighboring Imagawa clan struck, capturing castles at Washizu and Marune on the periphery of Nobunaga’s territory. With the visionary goal of seizing the imperial seat of power at Kyoto and declaring himself shogun, Imagawa Yoshimoto marched at the head of 25,000 men. While the Imagawa army rested in a distant gorge, Nobunaga force marched 3,000 Oda warriors into position and ambushed the far larger enemy force in a legendary victory that boosted his and his clan’s prestige.

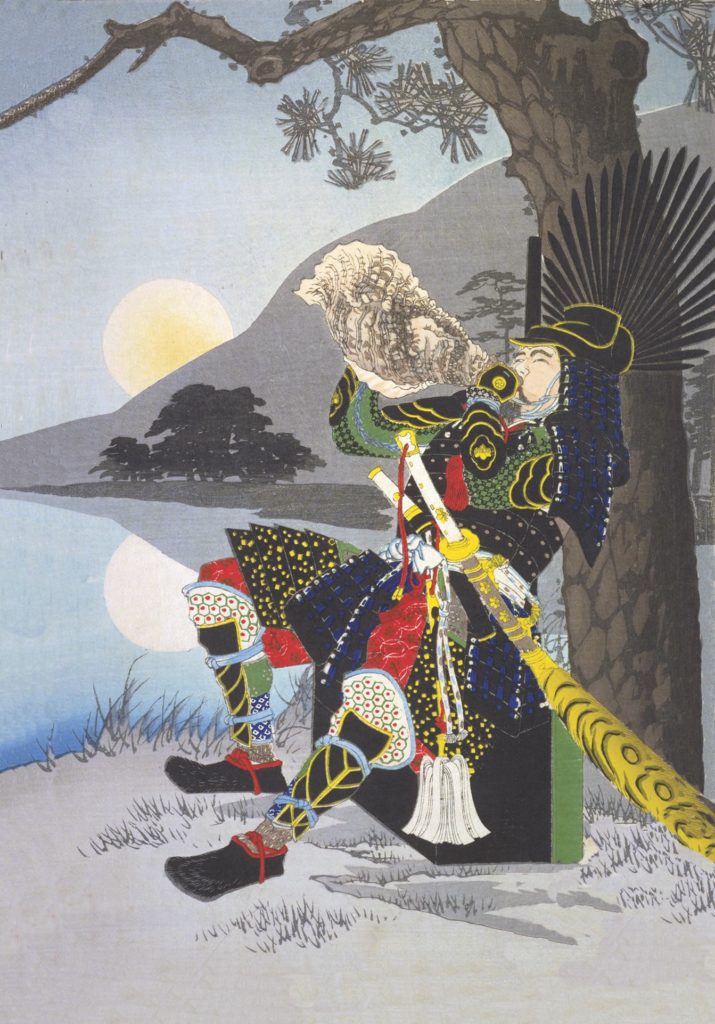

Samurai (Japan’s hereditary military nobility) flocked to his banner. Among them was an ambitious peasant named Kinoshita Tokichiro, who was destined for things far greater than his humble birth suggested. Generations of Japanese would come to know him as Toyotomi Hideyoshi.

Nobunaga’s victory at the 1560 Battle of Okehazama sent the Imagawa into steep decline, weakening the clan’s hold over lesser daimyo and allowing them to be poached by Nobunaga. Among the spoils were Matsudaira Moto-

yasu, his lands and his small but capable army. Motoyasu would become known to history as Tokugawa Ieyasu. Thus by 1561 all three warlords who would forge a unified Japan had surfaced in the historical record.

That same year, with the death of a key rival, Nobunaga moved on Mino Province, due north of his base in Owari. Capping off that campaign in 1567, he seized Inabayama Castle, an imposing fortification more than 1,000 feet above the valley floor with clear lines of sight in all directions. Renaming it Gifu Castle, Nobunaga made it his headquarters, while a network of lower castles barracked his growing army. As his power grew, Nobunaga adorned the fortified complex with increasingly luxurious palace grounds at the foot of the mountain. It remained his primary residence until the completion of Azuchi Castle in 1579.

With Mino secured and his forces ensconced around Gifu, Nobunaga marched on Omi Province, the gateway to Kyoto. His ostensible intentions were to install Ashikaga Yoshiaki as shogun to resolve a succession dispute within the latter’s failing shogunate.

This was Nobunaga’s moment, and he clearly recognized it as such. His troops effortlessly rolled across Omi and entered Kyoto in 1568, bringing him instant fame for the rapidity and decisiveness with which he’d struck.

Securing the support of the new shogun—who, after all, owed his succession to the Oda clan—Nobunaga headed north into Echizen Province in 1570 to take on the allied Asakura and Azai clans. Though he faced an initial setback from a growing anti-Oda alliance, by 1573 he had crushed both the Asakura and Azai, seizing their respective Ichijodani and Odani castles and forcing their leaders to commit seppuku (ritual suicide).

Nobunaga then turned his wrath on the Ikko-ikki, a militant Buddhist sect that had joined the doomed opposition forces and fought him in the past. Pitting an army of religious zealots against Nobunaga’s seasoned samurai warriors, the resulting campaign featured prolonged sieges of Nagashima Castle and the fortified temple complexes of Mount Hiei and Ishiyama Hongan-ji, the main Ikko-ikki stronghold at Osaka. While the sect survived the onslaught, it lost all momentum and was eradicated as an effective armed force.

By 1573 the shogun, Yoshiaki, had tired of being a puppet and threw his support behind Nobunaga’s enemies. In response the mighty warlord deposed the thankless Yoshiaki. Having made himself the most powerful daimyo in all Japan, Nobunaga inevitably clashed with contemporary rivals. He proved equal to the task. Conflict with the potent Takeda clan, for example, all but ended after the Takeda rashly besieged Tokugawa-aligned Nagashino Castle in 1575, prompting a forced march by Oda and Tokugawa warriors to relieve its defenders. In the resulting battle Nobunaga’s and Ieyasu’s allied forces decimated Takeda’s vaunted cavalry corps with what was arguably history’s first recorded use of volley fire by massed firearms.

With these victories Nobunaga, with clear designs on further conquest, secured control of central Honshu. He had refused several official titles offered by the deposed shogun, leaving no doubt who was really in charge. But treachery waited in the wings.

In 1582 one of Nobunaga’s subordinate generals, Akechi Mitsuhide, directed his army to surround Honno-ji Temple, where the daimyo was enjoying a tea ceremony with only his bodyguard and servants in attendance. The subsequent skirmish was fierce, but Nobunaga was trapped and committed seppuku rather than suffer the shame of capture.

To keep his head from falling into the traitor’s hands, he ordered his page to set the temple ablaze around them.

Thus ended the life of Japan’s most auspicious military leader to date. It remains unclear what motivated Mitsuhide to rebel against his liege. What is clear is that the general sought to turn the murder into a coup, sending out letters entreating the Mori clan to join him.

Hideyoshi, out east pressing the Mori on Nobunaga’s behalf, promptly terminated his campaign and returned to Kyoto like an avenging angel. Defeating Mitsuhide days later at the Battle of Yamazaki, Hideyoshi then stepped into the shoes of his late patron as leader of the consolidated forces.

hideyoshi the Former Peasant

Born in Nakamura to peasants in 1536, Hideyoshi blazed the most remarkable path to success recorded in the Sengoku period. His father had served among the ashigaru—peasant foot soldiers who constituted the rank and file of the samurai armies. While many legends obscure Hideyoshi’s upbringing, he is thought to have been initially subordinate to the Imagawa before absconding with funds entrusted to him by that clan. By 1558, however, Hideyoshi was firmly in the employ of Nobunaga.

Nobunaga must have divined something special in the lowborn ashigaru, as he entrusted Hideyoshi with ever increasing responsibility, such as repairing fortifications and negotiating on his master’s behalf. The relatively easy 1561 seizure of Inabayama Castle is thought to have reflected Hideyoshi’s efforts, and by 1568 he was one of Nobunaga’s favorite generals. In 1573, following several successes, including a successful rearguard action that shielded his lord’s withdrawal from Echizen Province, Hideyoshi was made a daimyo in his own right, and the Oda clan granted him three districts in Omi.

His steady ascension of the ranks put Hideyoshi in precisely the right place after Nobunaga’s 1582 assassination. Having avenged his benefactor’s death, he assumed command of the largest Japanese army ever assembled. Perhaps more important, Hideyoshi shared Nobunaga’s vision for a unified Japan.

In a bold move Hideyoshi ordered the construction of a massive new fortress at Osaka. Built atop the very ashes of Hongan-ji Temple, in which Nobunaga had perished, the fortress represented an unambiguous statement of intent. Osaka Castle would remain the headquarters of the Toyotomi clan until its destruction in 1615. Having made all necessary logistical arrangements to see the project through, Hideyoshi put his army in order and drafted plans for continued conquest—though he first had to tie up a few loose ends.

Not everyone was happy a former peasant had assumed control of Oda’s armies. Among the disgruntled were Nobunaga’s surviving second son, Nobukatsu, who convinced the powerful Ieyasu of the legitimacy of his hereditary claim. The succession crisis precipitated inconclusive battles at Komaki and Nagakute. While the remarkable military leaders never directly faced one another in combat, Hideyoshi worked behind the scenes to inhibit Ieyasu’s allies, ultimately forcing the latter’s Tokugawa clan to come to terms. Ieyasu remained Hideyoshi’s ally, albeit a reluctant one, for the rest of the latter’s extraordinary life.

Ineligible to receive the title shogun due to his lowly birth, Hideyoshi arranged to have himself named kampaku, imperial regent, providing him necessary legitimacy. Under the auspices of that political mantle Hideyoshi then devoted his attentions to achieving Nobunaga’s goal. In 1585 he seized Kii Province, crushing the warrior monks of Negoro-ji (onetime allies of the extinct Ikko-ikki), burning neighboring Ota Castle to the ground and slaughtering anyone who escaped the conflagration.

Using Kii as a base, Hideyoshi sent a 113,000-man invasion force to Shikoku, the smallest of Japan’s main islands, where he crushed the ruling Chosokabe clan following a 26-day siege of Ichinomiya Castle. Expanding in multiple directions at once, he simultaneously attacked Etchu Province to the north with 100,000 men.

Having completed these conquests by 1586, Hideyoshi dispatched his half-brother to invade Kyushu, Japan’s third largest island. Meanwhile, Hideyoshi himself, with some 200,000 men, conquered all of western Honshu in a drive to link up with his brother. By year’s end the siblings met in Satsuma Province, at the southern tip of Kyushu, where they forced 30,000 warriors of the Shimazu clan to surrender.

That left only one major opposition clan: the Hojo of Honshu’s Kanto Region, centered on the fortified village of Edo (present-day Tokyo). Repositioning his forces, Hideyoshi launched the inevitable assault on the Hojo in 1590. In the final showdown at Odawara Castle his 220,000 troops faced some 82,000 Hojo defenders. By then Hideyoshi’s power was undisputed, and the end was never in doubt.

After a three-month siege Hideyoshi compelled the Hojo to surrender by means of an ingenious ruse. While investing Odawara, he ordered the construction of a new fortress, Ishigakiyama Ichiya, beyond a distant tree line. When its walls were complete—a feat accomplished in a mere 80 days—Hideyoshi had his men fell the intervening trees. Beholding what appeared to be an enemy fortress built overnight, the starving defenders lost their will to fight and surrendered. With that, all of Japan was under Hideyoshi’s dominion.

Yet unification created a new set of problems. The empire had been at war with itself for 123 years. Conflict was all Japan’s warrior class had known, thus the sudden arrival of peace generated tension.

Absent combat, how was an ambitious young samurai to achieve greatness? With internal warfare outlawed, how could one increase the lands of family and clan?

The samurai grew restless, nowhere more so than on Kyushu, where most warriors had surrendered rather than confront the massive invasion force. Just as threatening to Hideyoshi, who was a staunch Zen Buddhist, was the thoroughly foreign Christian religion practiced by large numbers of the Kyushu samurai.

The cunning kampaku soon devised a plan to rid himself of the most troublesome samurai while consolidating his rule back home. Hideyoshi fomented a foreign war, ostensibly affording an opportunity for the quarrelsome warriors to secure both lands and honor. In 1592, with the stated goal of conquering China and India, he launched back-to-back invasions of Joseon Korea.

Though the operations were poorly planned, Hideyoshi’s armies boasted significant tactical advantages over the Korean forces they encountered and thus pushed rapidly north, brushing aside all resistance. Ultimately, however, inadequate logistics, an ineffectual navy and intervention by the Ming Chinese undid the exertions of his soldiers. By the time Hideyoshi died in 1598, the Japanese had withdrawn to a string of fortifications along Korea’s southern coast, where they hunkered down, waiting for a chance to return home. Hideyoshi’s death, while a boon to the troops enduring privation on the continent, bred problems of its own. The kampaku left behind a single male heir, 5-year-old Hideyori. On realizing his life was ebbing, Hideyoshi had sought to ensure his toddler son’s rise to power by drawing chief allies and daimyos into a balanced regency of Hideyori.

Notwithstanding the regency or his oath to the dying kampaku, Ieyasu—the former vassal to Nobunaga and reluctant ally to Hideyoshi—wasn’t about to stand by and allow a child to rule Japan.

Ieyasu The Rebellious Vassal

Ieyasu was born in 1542 at Okazaki Castle, southeast of Nagoya. In 1548, amid the violent interclan politics of the time, the Oda abducted 6-year-old Ieyasu and held him hostage. Nobunaga’s father, Nobuhide, threatened to kill Ieyasu if the Tokugawa refused to sever all ties with the Imagawa. Though Ieyasu’s father refused, Nobuhide didn’t carry through with his threat. Had he done so, Japan’s history might have turned out very differently.

Ieyasu’s captivity, by first the Oda and then the Imagawa, lasted until he was 14, though as a potential future ally he was reportedly treated well. Once released to assume leadership of his clan, Ieyasu remained subordinate to the Imagawa and even led forces against the Oda for a time, by all accounts commanding well. The final defeat of the Imagawa in 1560 enabled him to assert a measure of independence, which he did by forming a lifelong alliance with Nobunaga.

Ieyasu was far more earnest in service to the Oda than to Hideyoshi, though why remains unclear. Perhaps he was disdainful of the latter’s humble origins, or maybe he foresaw he would have to contend with Hideyoshi for dominance.

Following Hideyoshi’s rise to power and the inconclusive power struggles that followed, Ieyasu negotiated an alliance with the former in 1585. Their combined victory at Odawara in 1590 left the whole of Hojo territory to be distributed as the kampaku saw fit.

Wisely uncomfortable with having Ieyasu so close to his base at Osaka, Hideyoshi offered him the eight provinces of the Kanto Region in exchange for lands near Nagoya. Ieyasu agreed, taking ownership of the rich plains east of Mt. Fuji. That in turn provided Ieyasu with the physical distance he would need to formulate his own plans for domination.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

In the wake of Hideyoshi’s 1598 death Ieyasu led an army west to Fushimi Castle, near Kyoto, within a day’s march of Osaka Castle, where the appointed heir, Hideyori, was being raised. This alarmed the other regents, who formed an alliance to oppose the potential usurper. The aggressive moves prompted a nationwide split into a western faction, supporting young Hideyori’s regency, and an eastern faction, allied with the Tokugawa clan.

In 1600 Ieyasu marched his forces north in a preemptive strike on the Uesugi clan, steadfast allies of Hideyori. Before he could land the blow, however, he received word a western army was fast approaching and turned to meet the greater threat. In the subsequent Battle of Sekigahara his 89,000-man eastern army met the 82,000-man western army in a fog-shrouded, confused engagement.

Amid the fighting Ieyasu’s preeminence as a strategist became evident, and a sizeable portion of his opponent’s force defected, leading to a decisive defeat of the westerners.

Over the next few days the victors hunted down and killed all surviving opposition leaders, leaving Ieyasu the master of all Japan.

Showdown at Osaka Castle

Though Ieyasu was declared shogun in 1603, a final act remained in the saga of Tokugawa hegemony. In 1614 young Hideyori, still alive despite so much death on his behalf, rallied dispossessed ronin (masterless samurai) and his late father’s onetime supporters into a force with which he intended to recover his birthright. Refusing Ieyasu’s order to abandon Osaka Castle, Hideyori instead prepared for war. Emerging from official retirement, Ieyasu led a 164,000-man army against the 120,000 westerners holding out inside the vast bastion, surrounding the fortress in January 1615.

The resulting siege of Osaka Castle is noteworthy for the presence of artillery on both sides—a rare sight on medieval Japanese battlefields. The shogunate fielded more than 300 pieces, including light Japanese cannons and larger, long-range European guns. Having failed to breach the outer walls by direct assault over the course of six weeks, Ieyasu resorted to a continuous, heavy bombardment and within three days negotiated a cease-fire. Yet Hideyori continued his saber-rattling.

The impasse stretched into summer when Ieyasu returned and, in a signal victory south of Osaka at Tennoji, solidified his reign and that of his descendants. It was Ieyasu’s final battle, and with it he cemented the unified Japan we recognize today.

Contemporary Japanese acknowledge with reverence the work of their three great unifiers. Oda Nobunaga, Toyotomi Hideyoshi and Tokugawa Ieyasu took a continually warring mass of feudal domains and mercilessly hammered them into a nation.

In present-day Japan, the only country in the world with a pacifist constitution, there is no pining for a return to those bellicose times, when wars never ceased, and samurai held the power of life and death over everyone. Yet there remains a very real sense Japan would not be the nation it is today had it not passed through such a fiery crucible. Thus its people maintain tremendous pride in the accomplishments of these three men, uttering their names with all the respect and admiration they earned by conquest at the edge of the sword. MH

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.