Straddling a lucrative trade route between empires, the island realm of Ryukyu surrendered its sovereignty to Japan in 1609

Conspicuously dressed in a gold-embroidered blue frock coat with epaulets, the U.S. Navy flag officer carefully wandered through weathered stone ruins on the East China Sea island of Okinawa. Marveling at the craftsmanship of Nakagusuku Castle, he explored the grounds as if on holiday, oblivious to any potential danger from locals who’d gathered to gawk at the new and clearly important arrival. Ignorant of the island’s long history and that of the people who called it home, Commodore Matthew C. Perry could only appreciate the fortifications for their imposing military beauty. The year was 1853. He carried a stern message for the islanders and their Japanese overlords—open for trade, or else.

Many today are doubtless aware of Okinawa’s significance in modern history. The brutal 98-day battle fought there near the end of World War II has assured the island a fearsome place in military lore. Yet the saga of the Kingdom of Ryukyu—as the archipelago was known when Perry visited—is far longer and more complex. The story of how the Japanese seized the once prosperous realm is a fascinating tale, whether viewed through a military, economic or political lens.

The first people to settle in the Ryukyus arrived some 32,000 years ago. The same East Asian migration that contributed to the formation of the Yamato people—known today as the Japanese—helped populate the archipelago’s 100-plus islands, which stretch nearly 400 miles from Kyushu, the southernmost of the Japanese Home Islands, southwest to Taiwan. For centuries mariners from China and Southeast Asia had found themselves shipwrecked on Ryukyu beaches. Forgoing attempts to get home, they built new lives where destiny had stranded them. The mixing of these strains of East Asian DNA meant the people of Ryukyu were exposed to a wider range of influences than surrounding societies. The resulting culture was distinct from those of the Japanese, Chinese and Koreans then taking center stage in the region.

Despite the kingdom’s total land mass of just under 877 square miles, by 1314 it had split into three separate principalities centered on Okinawa—Hokuzan in the north, Chuzan in the center and Nanzan in the south. Each lord ruled from his own castle, at Nakijin, Shuri and Ozato, respectively. Following a century of warfare and the construction of multiple castles, the lord of Chuzan subdued his neighbors by 1429, ushering in more than two centuries of consolidated rule.

Military activity during the period was limited to sporadic disputes with Japanese clans over the Amami Islands, north of Okinawa. Such tiffs were rare, as the peaceful kingdom looked to capitalize on its unique position in the world. Lying along the major trade route from Malay and Siam to both Japan and Korea, the Kingdom of Ryukyu benefited from its reputation as a hospitable stopover for mariners. The stream of foreign goods brought the kingdom great wealth—a fact noticed by both the Ming court in China and feudal lords in Japan.

The Ming consistently wrote of the “civilized” nature of trade envoys from “Lewchew,” who first visited the mainland in 1374. Given the Ming dynasty’s generally poor relationship with Japan, the Chinese repeatedly called on Ryukyuan kings to mediate, though never to any appreciable effect. Those failures aside, Ming China considered Ryukyu a tributary state.

Regardless of the Chinese stance, Japanese rulers of the Kyushu province of Satsuma had long claimed the islands to the south. As early as 1206 one of the official titles of the Japanese ruler in Kagoshima Castle was “Lord of the Twelve Southern Islands,” in reference to the Ryukyus. But as the Satsuma lacked the strength and desire to seize and hold the archipelago, the title was a mere pretense.

Beginning in 1467, the Sengoku (“Warring States”) period of Japanese history focused all the energy of the samurai in a seemingly endless series of internal conflicts. The period culminated in 1587 with Toyotomi Hideyoshi’s campaign to conquer Kyushu. Within a few years he’d defeated the last of his rivals, completing the long-sought unification of Japan. Satsuma suddenly found itself a vassal state. Thus when Hideyoshi launched his ill-fated invasions of Korea in 1592 and ’97, the province provided more than 10,000 troops for the endeavor. As Satsuma’s ostensible tributary, Ryukyu was also ordered to provide support. Hoping to assuage Hideyoshi yet provoke neither the Koreans nor the Chinese, the tiny kingdom supplied only minimal rations for the invasion troops.

The failure of those two invasions and a subsequent succession dispute following Hideyoshi’s 1598 death proved disastrous for the Kingdom of Ryukyu, though it was unforeseeable at the time.

The Shimazu clan, which had ruled Satsuma and surrounding provinces since 1196, was a prosperous and venerable samurai family. Descended from the legendary Minamoto line, the Shimazu were famous for the extreme loyalty of their retainers and troops. The clan had done well during the Sengoku period, but due to its submission to Hideyoshi, the loss of thousands of its warriors in Korea and defeat by feudal forces under Tokugawa Ieyasu at the 1600 Battle of Sekigahara, the Shimazu found themselves in dire straits. Over the following decade they actively pursued all opportunities to turn around the clan’s fortunes.

The rich trade flowing through Ryukyu offered irresistible temptation for the combative Shimazu. Given the clan’s existing—albeit tenuous—claim to the islands, an expedition to decisively seize the lucrative trade route offered more than just the prospect of material gain. It represented an opportunity to appease the Tokugawa administration in faraway Edo (present-day Tokyo), secure territory in the name of the shogun and facilitate the payment of taxes.

Chafing at Ryukyu’s repeated refusals to formally submit to his authority, the shogun, Tokugawa Hidetada, agreed to and authorized the 1609 invasion. Shimazu Tadatsune, the lord of Satsuma at the time, ordered the assembly of 3,000 samurai and loyal ashigaru. Supporting these horsemen, spearmen, archers and harquebusiers were 2,000 laborers and 3,000 sailors manning a fleet of some 100 ships. Comprising veterans of the Sengoku period, the Korean campaigns and the doomed struggle against the Tokugawa, this army was a brutally efficient and frightful adversary.

The elite corps of samurai were far more effective than might be expected of such a small force. On April 8 Tadatsune ordered his army to set sail under senior commander Kabayama Hisataka.

Sho Nei, sovereign of Ryukyu, had been warned of the impending assault. Convinced the Shimazu thrust would be limited to the Amamis, the king ordered reinforcements north to the islands of Oshima and Tokunoshima. But the speedy Japanese advance would dash all hopes to limit fighting to the kingdom’s northern periphery.

The island of Okinawa itself appeared well prepared to deal with invasion, certainly one by such a miniscule enemy force. A network of stone castles (gusuku in the Ryukyuan language) stretched some 40 miles north to south, from Nakijin to the palace in Shuri. Multiple lesser bastions dotted the island’s many steep hills, with major fortifications at Nakagusuku and Katsuren and the largest of all at Urasoe.

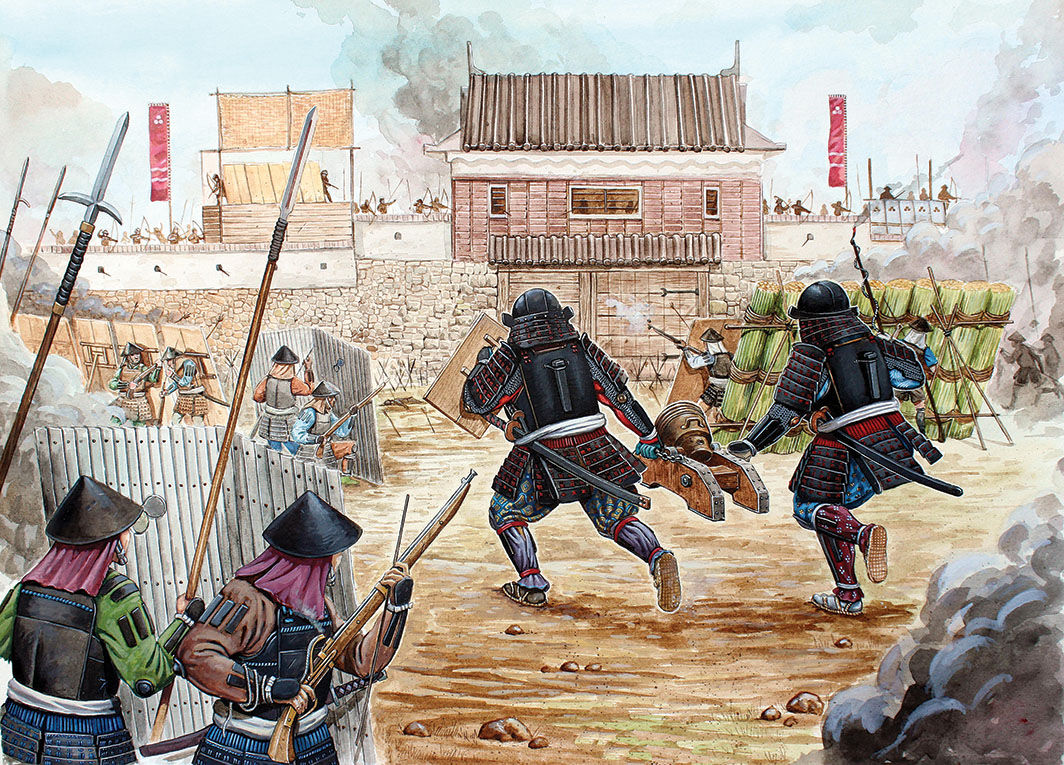

Befitting a people with multicultural origins, the gusuku borrowed from its forbears’ fortifications. Tracing the landscape like the terrain-following walls of China and Korea, the gusuku also featured a series of overlapping baileys topped by wooden structures, as found in Japan. Sited exclusively on high ground, their stone parapets rose to impressive heights, enabling sentries to quickly spot and isolate would-be attackers. That said, gusuku walls lacked crenellations through which to peer or fire, leaving exposed defenders vulnerable to the type of long-range, massed harquebus fire the Japanese had perfected during the Korean campaigns. That design flaw would have dire repercussions in the coming battle.

While Shuri Castle sheltered Sho Nei and served as the seat of royal authority, the port of Naha, a few miles west, represented the vital artery through which trade and diplomacy were carried out. Realizing the growing importance of Naha, the court in 1546 had ordered the construction of harbor fortifications and a road to link Shuri with the port. Intended to defeat periodic attacks by pirates, the defenses at the time of the invasion comprised Yarazamori and Mie, sister stone fortresses that jutted into the sea on either side of the anchorage. Suspended between them was a giant iron net that defenders could lower to permit entry or raise to seal off the entrance.

As strong as the fortifications were, the army defending Ryukyu was vastly inferior to the veteran samurai force headed their way. Ryukyuans had not fought a major campaign on their home turf in more than two centuries. Infrequent skirmishes on faraway islands couldn’t possibly have prepared them for the coming storm. The king’s troops were armed with a hodgepodge of traditional Japanese and Chinese arms, including spears, bows, short swords and archaic, tri-barreled Chinese-style firearms eclipsed in both range and accuracy by the Portuguese-derived harquebuses of the Shimazu.

The Japanese landed at Oshima on April 11, touching off the campaign. Easily brushing aside the weak resistance of local Ryukyuan forces, the invaders swept south across the island, securing it by the 20th. For the first time in two centuries Oshima was under direct Shimazu control—an auspicious beginning to the endeavor.

The invasion force then sailed south, landing at Tokunoshima on the 24th. There the Shimazu met their first significant resistance, some 200 to 300 troops under a son-in-law of Jana Teido, a member of Sho Nei’s Sanshikan (“Council of Three”), the king’s closest advisers. Though poorly armed, the defenders fought fiercely before withdrawing under withering gunfire. Japanese attempts to pillage local dwellings met with further resistance as the peasantry, wielding hatchets, defended their homes with savage intensity.

On April 28 the invaders boarded their vessels and continued south to Okinoerabujima, which promptly surrendered without a fight. As it marked the last major island north of Okinawa proper, the troops were grateful for the chance to recuperate and prepare for the final phase of the operation.

The next morning the fleet dropped anchor in Unten harbor on the northeast side of Okinawa’s Motobu Peninsula. A large, sheltered anchorage, Unten was dominated by Nakijin Castle, an expansive fortification and the seat of Ryukyu rule in northern Okinawa. Yet its garrison made no attempt to stop the Japanese from landing. Instead, garrison commander Sho Kokushi, the warden of the north and Sho Nei’s son and heir, sent word to Shuri reporting the situation and pleading for reinforcements.

Unsure just where along the nearly 300-mile-long coastline the invaders might land, the main Ryukyuan army had gathered in a central location, ready to march in any direction on short notice. A thousand troops immediately headed north to secure Nakijin against the impending attack.

Kabayama stormed the fortress on April 30. The fighting was brief and intense, resulting in the death of Sho Kokushi and fully half of the force dispatched to hold the citadel. It is unclear whether the reinforcements made it in time to defend the castle or engaged the Japanese after its fall. Regardless, the stronghold and a significant portion of Sho Nei’s army were lost.

Having secured the fortress, the samurai boarded their ships and headed down the west coast, making landfall May 3 at Yomitan, near Zakimi Castle. To the east and south, respectively, stood Katsuren and Nakagusuku castles. Though the trio of garrisons represented the fortified heart of the kingdom, none was willing to leave its fortifications and risk meeting the Shimazu in the open.

To strike terror in peoples’ hearts, Kabayama burned the village at Yomitan in full view of Zakimi’s ramparts. He then split his army into sea and land forces, the former embarking south for Naha, the latter heading inland toward Shuri Castle and the defiant king ensconced within.

Marching rapidly overland, the Japanese took massive Urasoe Castle in stride, looting and then torching adjacent Ryufuku-ji Temple. Resuming their march toward Shuri, they ransacked and burned structures along the way, further spreading panic among Sho Nei’s fleeing subjects.

In a final, ill-fated attempt to prevent the invaders from reaching the capital, General Goeku Ueekata sought to hold the Taihei Bridge, a narrow stone span at Tairabashi, with a mere 100 men. The Japanese decimated the holding force with gunfire, then beheaded one of its wounded officers, scattering defenders who had never witnessed volley harquebus fire, not to mention such naked brutality. The road to Shuri lay open.

Off the coast a few miles to the west, Kabayama’s fleet was far less successful in its attempt to secure Naha, the ultimate prize. On May 4 cannons from the Ryukyuans’ flanking fortresses pummeled Shimazu vessels, preventing Kabayama’s flagship from even nearing the imposing works. Manning the ramparts at Yarazamori, Jana Teido and 3,000 men repulsed the attack with cannon and small-arms fire. The invading ships quickly fell back out of range amid the exultant cheers of the defenders. Yet the shrewd invaders may have achieved exactly what they’d intended.

In deploying so many of Ryukyu’s limited forces to protect Naha, Sho Nei had left Shuri Castle vulnerable to the battle-hardened contingent of samurai marching down on it from Tairabashi. Kabayama’s abortive attack on the port froze the bulk of the Ryukyuan army in place when it should have been inland defending Shuri. The king would live to regret his mistake, but by the time his advisers realized what was afoot, it was too late.

On May 4 the Shimazu advanced uphill toward the red palace walls of Shuri, pausing only to rain fire on the ramparts. While Japanese harquebusiers effectively kept the defenders’ heads down, the ashigaru brought up scaling ladders. Samurai soon poured over the ramparts, taking Shuri’s lower baileys one after another.

The assault came so fast that courtiers scarcely had time to flee. The only potential obstacle to Kabayama’s plan was an unconventional ploy by the desperate defenders. According to local lore, days in advance of the approaching threat islanders had scoured the jungle for as many of the indigenous—and highly venomous—habu snakes as they could find, then deposited the vipers along the route of attack. Even if true, clusters of venomous reptiles could not undo what was in motion.

Still at his command post when Shimazu troops burst into the palace courtyard, Sho Nei promptly surrendered to avoid further bloodshed. Leaving a small detachment to guard the king, the Japanese turned their attention on the defenses guarding Naha, which were virtually unprotected from a landward approach. In short order the fleet was able to safely enter the port, and the victorious invading army was once again reunited.

In the aftermath of the invasion the Japanese transported Sho Nei and his senior advisers to Satsuma as hostages. Finally, in 1611 Shimazu Tadatsune sent the captive king and his advisers to Sunpu to meet with the retired Tokugawa Ieyasu, then on to Edo to appear before Ieyasu’s son, Hidetada, the current shogun. Before permitting Sho Nei and the others to return home, Hidetada compelled them to swear a humiliating oath of loyalty, acknowledging fealty to the lord of Satsuma.

In a gruesome coda to the drama, Sho Nei’s Sanshikan adviser Jana Teido, the brave defender of Naha, refused the Tokugawa terms and was beheaded on the spot.

Having won their prize, the Shimazu had also earned the regard of Japan’s new shogun. But their work was far from done. First, Kabayama dispatched the surviving members of the Ryukyuan Sanshikan southwest by ship to Miyako and Kumejima islands to secure their surrender. That achieved, the Shimazu packed up and went home, leaving behind a handful of samurai as a makeshift occupation force. A small footprint would be necessary if the victors were to truly capitalize on the endeavor.

The Ming court was fully aware of the change in sovereignty of their lucrative trading partner. While direct trade between Japan and China was illegal—the Japanese having consistently refused to accept the tributary relationship required by the Ming—Tadatsune gambled on China’s willingness to look the other way if not confronted directly with a contradiction to that policy. His assumption was correct.

Over the next three decades, whenever Chinese ships arrived in port, the Shimazu overseers discreetly withdrew into the jungle until the visitors left. This charade continued until 1644 when the Manchus toppled the Ming, ending the long-standing tributary relationship with Ryukyu. In 1655, with the blessing of the Tokugawa shogun, the archipelago re-established tributary relations with the Qing dynasty. By then, however, all trade profits went directly to the Shimazu, and Ryukyu started its long slide into servility.

Commodore Perry knew none of this when he visited Shuri Castle. Yet his appearance in Ryukyu alarmed the Japanese, sparking an imperial resurgence known as the Meiji Restoration. The forces he unleashed would alter the trajectory of the history of Japan and all but destroy the idyllic island kingdom to its south.

Japan allowed Ryukyu the trappings of sovereignty until 1879, when it annexed the kingdom as the Okinawa Prefecture. From that time, in accordance with Meiji-era policy, the language and culture of ancient Ryukyu were all but erased. That process was ongoing when Okinawa became the last great battlefield of World War II. The archipelago remained under U.S. military control until 1972, when the Americans returned the once prosperous and independent Ryukyus to Japanese control. MH

U.S. Army veteran M.G. Haynes is an author of military and historical fiction with a degree in Asian studies. For further reading he recommends Okinawa: The History of an Island People, by George H. Kerr, and The Samurai Capture a King: Okinawa 1609, by Stephen Turnbull.

This article appeared in the July 2021 issue of Military History magazine. For more stories, subscribe here and visit us on Facebook: