Admiral Heihachiro Togo surprising military victories opens the door to the Rising Sun’s catastrophic era of militarism.

On the evening of February 8, 1904, life in the Russian military encampment at Port Arthur was good. The commander of the Russian Far Eastern Fleet, Vice Adm. Oskar Victorovich Stark, was hosting a reception for the senior administrators of Czar Nicholas II’s far-flung Asian dominions. The dignitaries included Stark’s superior, Adm. Evgeny Aleksiev, and Aleksiev’s chief of staff, Vice Adm. Vilgelm Vitgeft. Champagne flowed freely. Although tensions between Russia and Japan were high, Port Arthur seemed secure, protected as it was by no fewer than seven battleships outside the harbor. But even as toasts were exchanged, a Japanese fleet led by British-trained Adm. Heihachiro Togo was about to launch the most successful surprise attack by any modern navy up to that date.

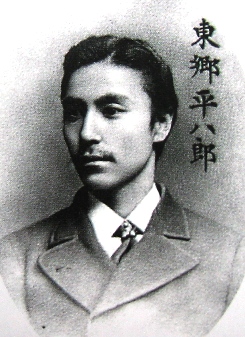

Standing aboard his flagship, the Mikasa, Togo’s slight stature belied his strategic prowess. He stood barely five-foot three-inches tall and weighed about 130 pounds. He had health problems stemming from what was diagnosed as severe rheumatism, which in the 1880s had almost obliged him to retire. His one indulgence was alcohol; he would later observe that “No teetotaler can be a really capable man.”

And he did not hesitate to crash this Russian cocktail party, launching torpedoes and later, artillery shells, to devastating effect. Indeed, his success this night, and a still greater victory over the Russian High Seas Fleet 15 months later, would mark the emergence of Japan as a world power and establish Togo as the “Japanese Nelson”—a comparison to legendary British Vice Adm. Horatio Nelson, who led England to victory during the Napoleonic Wars. Politically, however, this first modern-era defeat of a European power by an Asian nation would mark the emergence of a catastrophic period of Japanese militarism, one that would come to a close only with Japan’s surrender in 1945—and only after the United States annihilated two of Japan’s major cities with atomic bombs.

Heihachiro Togo, who was 56 at the time of the attack on Port Arthur, was born in 1848 on the island of Kyushu. His mother was a noblewoman and his father a samurai and a senior administrator who would serve for a time as a district governor in Satsuma province. Togo’s parents named him Nakagoro at birth, but at age 13, in accordance with samurai tradition, Togo chose the name Heihachiro—“peaceful son”—by which he would be known the rest of his life.

Although Togo’s father was not a military man, the military services were held in such high esteem that the future admiral and his two brothers all chose to serve in the provincial navy. As a young man, Togo served as a gunnery officer on the warship Kasuga in an action off Awaji Island during the 1868 uprising that overthrew the Tokugawa shogunate. The following year, he was absorbed into the new Imperial Navy at a rank equivalent to midshipman, and in 1871 he was one of 12 naval cadets who were sent to Britain for training.

Togo trained at the Thames Nautical Training College, circumnavigated the globe as an ordinary seaman aboard the training ship Hampshire, studied mathematics at Cambridge, and closely monitored the construction of one of three armored cruisers destined for the Japanese navy. At a shipyard on the Thames, a companion recalled, he “persisted in asking questions with a tireless politeness which soon got the better of the rather surly temper of the shipbuilding workers.” In all, Togo would spend more than four years away from his homeland.

The years in England left their mark. For Togo and probably his peers, the Royal Navy became the standard by which all naval matters were judged. Equally important, his training in England had kept Togo away from his homeland in a dangerous and divisive period. His two brothers chose the wrong side in a feudal uprising and were killed. But young Heihachiro returned to Japan in 1878, alive and newly promoted to lieutenant.

The gradual disintegration of the Chinese empire in the latter half of the 19th century held implications for all of northeast Asia. Power abhors a vacuum, and while Russia sought to expand its influence in Manchuria, Japan sought to make Korea—long a vassal of China—a Japanese dependency and economic satellite.

When a rebellion broke out in southern Korea in 1894, the court at Seoul asked China for help, and Peking sent a few troops. Japan, meanwhile, sent some 10,000 soldiers, who seized the king and dared China to respond. War broke out when Togo, commanding the cruiser Naniwa, challenged a British-flag transport, Kaosheng, that was ferrying Chinese troops to Korea. When the ship’s British officers refused to follow the Naniwa to a Japanese port, Togo opened fire on the Kaosheng and sank it. He rescued the ship’s European officers but fired on Chinese soldiers in boats and in the water. The code of Bushido—“the way of the warrior”—made no provision for the rescue of enemy common soldiers.

The resulting Sino-Japanese War ended in a quick victory for the Japanese and first brought Togo to the attention of the Japanese populace. He also won praise from his superiors for his performance with the Naniwa in Adm. Yuko Ito’s crushing defeat of a Chinese fleet near the Yalu River on September 17, 1894.

As commander of the Naniwa, Togo embodied the characteristics of an emerging military class based on the concept of Bushido. Disciples of Bushido held that the warrior should enjoy the highest status in society. In return, he was expected to be sincere, manly, stoic, and totally devoted to his feudal lord and his comrades. Family and loved ones were subordinated to honor and trust among fellow samurai. As a disciple of Bushido, Togo was proud but never boastful.

Elation in Japan over the easy defeat of China soon gave way to resentment. Under the terms of the Treaty of Shimonoseki, signed on April 17, 1895, Japan initially gained Formosa, the Pescadores Islands, and the Liaotung Peninsula, including the strategic Port Arthur. Japanese control of that city displeased the Russians, who had long sought a warm-water port on the Pacific. Russia intervened, declaring that the fruits of Japan’s victory “constituted a perpetual menace to the peace of the Far East.” Japan, not yet ready for war with a European power, was forced to give up Port Arthur.

Responding to that humiliation, however, Japan began a fateful military buildup. The nucleus of a new battle fleet was to be four battleships under construction in Britain. The vessels were to be compatible in speed and armament with Japan’s two existing battleships, and to embody the latest in naval technology. Although the new navy was dependent on British technology, the Japanese added some wrinkles of their own. Because they expected their fleet to operate close to home, the Japanese were able to substitute extra armor for bunkers that other navies devoted to coal. Japanese munitions incorporated an explosive discovered by the French. It generated more heat than traditional explosives, and would prove highly effective when employed together with armor-piercing shells.

At the Naval Staff College at Sasebo, Togo and his comrades studied naval strategy, including the theories of American naval strategist Alfred Thayer Mahan. They combined Mahan’s emphasis on fighting a decisive battle with the aggressive spirit of Japan’s own Bushido tradition. Central to Japanese doctrine were two assumptions: that a Japanese fleet would be faster and more maneuverable than that of its enemy, and that Japan would strike first.

In late May 1900, the violent Boxer Rebellion in China threatened the diplomatic community in Peking and led foreigners to take refuge in the international quarter. In June, the Japanese government ordered Togo to join the fleet in China that was supporting the international ground force marching to the relief of Peking. Togo studied the ships of other nations, especially Russian vessels, and took close note of the Russian sailors’ lax discipline and poor training.

Japan and Russia appeared to be on a collision course, for construction of the Trans-Siberian Railroad, begun in 1891 and nearing completion, suggested to the Japanese that Czar Nicholas was attempting to bring Korea into Russia’s sphere of influence. In 1902, Japan and Britain signed a treaty that pledged each country to neutrality if the other were to go to war with a third party. The effect of the treaty was to give Japan a free hand in dealing with the Russians.

The prospect of war with Japan did not greatly concern Czar Nicholas and his court. It was inconceivable to them that the Russians might be defeated by the Japanese, whom Admiral Aleksiev, the czar’s supreme commander in Asia, was said to regard as “insignificant vermin who must be destroyed.” Beset with unrest at home, the czar’s reactionary ministers thought “a little victorious war” against Japan might serve to unite their people.

The Russians greatly underestimated their enemy. By 1904 the Japanese possessed 12 capital ships, none more than five years old. These constituted a fleet quite capable of taking on the Russian Far East Squadron based at Port Arthur, as long as it did so before the Russians sent reinforcements from the Baltic.

Yet Japan did not initially seek war. In an attempt to postpone a conflict, the Japanese offered Russia a free hand in Manchuria in return for a disclaimer of any Russian interest in Korea. In view of Russia’s unpreparedness for war, St. Petersburg would have done well to negotiate with Tokyo. Instead, it responded to the Japanese proposal with delay, followed by rejection.

Now determined on war, the Japanese intended to invade Manchuria by landing an army in Korea and driving north across the Yalu River. Additional troops would be taken to the Liaotung Peninsula to move on Port Arthur by land, but supplying and reinforcing these troops required that Japan gain control of the sea.

As war loomed, Togo was promoted to vice admiral and placed in command of the Combined Fleet, a post subordinate only to the chief of the navy staff. He was a popular choice, for the admiral was by then widely known for his bravery, judgment, and professionalism. On the evening of February 5, 1904, Togo called his senior commanders to meet on his flagship at Sasebo. There he told them that they would move immediately to attack the Russian fleet outside Port Arthur. Togo’s torpedo boats, employing British Whitehead torpedoes, would spearhead the attack.

As Togo’s commanders returned to their ships, a sense of excitement spread through the fleet. Anchor chains clanked and signal flags cracked in the cold air. Cries of “Banzai!” broke out as the emperor’s sailors realized that they were off to war.

Togo had prepared meticulously. His crews were well trained and motivated, and spies had informed him of the location of every enemy ship. Just before midnight on February 8, 1904, a volley of torpedoes from 10 Japanese torpedo boats badly damaged three Russian warships. Two picket ships had spotted the incoming enemy flotilla but, lacking wireless telegraphy, had been unable to warn Port Arthur. The Russians were taken completely unawares.

After the destroyers had withdrawn, Togo prepared to renew the attack in daylight. His flagship, the 15,400-ton Mikasa, was one of six modern battleships purchased from Britain in 1893 and 1894, and the 12-inch guns of the Japanese fleet were as powerful as those of any warship afloat.

As dawn broke on February 9, residents of Port Arthur were astonished to see three Russian warships beached in shallow water outside the harbor entrance. The cruiser Pallada had settled near the western side of the harbor. The battleships Retvizan and Tsarevich had grounded in the harbor entrance, partially blocking it. Around noon the next day, Togo followed up the torpedo attack, leading his line of battleships from west to east to bombard the port. Accurate Japanese gunnery damaged several vessels, but Russian shore batteries eventually got the range, and three of Togo’s ships suffered damage as well.

At the same time that its navy was attacking Port Arthur, Japan was landing ground forces in Korea and northern China. Tokyo’s naval strategy was aimed at neutralizing Port Arthur and gaining command of the Yellow Sea to protect transports ferrying Japanese troops to Korea. Although Russia’s Far Eastern Fleet had not been destroyed, it had been effectively bottled up, and the Japanese army’s amphibious operations proceeded without incident.

Japan and Russia both declared war on February 10, by which time the first phase of their naval conflict was over, but the war would continue for 18 months.

With his surprise attacks on February 8 and 9, Togo had not achieved the decisive battle he sought, but he had done as well as could reasonably have been expected. He had sunk or damaged half of Russia’s Port Arthur fleet and bottled up the remainder, dealing a blow to enemy morale from which it would never recover.

Having gained control of the sea, Japan was free to operate as it chose on land. An army of 20,000 landed at Inchon, Korea, and marched north. A second army marched south and laid siege to Port Arthur. Russia was bringing additional troops east along the unfinished Trans-Siberian Railroad, and time was not on the side of the Japanese. Nothing was left to chance, writes historian Richard Connaughton: “Blankets and mounds of rice appeared as if by magic. Herds of cattle, observed and noted by Japanese agents living among the Koreans, were bought, collected and driven toward [a] depot.…When the tired troops arrived…quarters had been prepared for them, fires were lit in the streets, and field kitchens provided hot food.”

From the beginning, the war was an unequal contest. Although Russia’s army was five times the size of Japan’s, its forces were scattered across a vast country and the best troops were not in the Far East. The Japanese managed to place 150,000 men on the Asian mainland where they faced only 80,000 regulars and 23,000 garrison troops. Logistical problems for the Japanese were minor compared with those of the Russians, dependent as the latter were on a single-track railroad. With luck, a train might cover the 5,000 miles from Moscow to Vladivostok in 15 days, but it was not unusual for such a trip to take 40 days.

On May 1, the Japanese decisively defeated a Russian force on the southern end of the Yalu River, and the Russians suffered a succession of setbacks over the next few months. The energy and efficiency of the Japanese army, led by Gen. Maresuke Nogi, contrasted starkly with the chaos and confusion among the Russians. By mid-June, four Japanese divisions were moving closer to Port Arthur. Through the summer and fall of 1904, Japanese infantry would storm one Russian bastion after another. Japanese casualties were heavy, but Port Arthur’s fate was sealed.

In St. Petersburg, Czar Nicholas watched with dismay as disaster followed disaster. He thought of leading his troops in person, but was dissuaded by his courtiers and settled for changing commanders. On March 8, Vice Adm. Stepan Osipovitch Makarov arrived in Port Arthur in place of the luckless Stark, and four days later the czar appointed his former minister of war, Gen. Aleksei N. Kuropatkin, as land commander. Neither man underestimated the Japanese threat.

In a memorandum written in April, Kuropatkin wrote, “In the Japanese we shall…have very serious opponents, who must be reckoned with according to European standards.”

Makarov, whom Togo regarded as the ablest Russian admiral, took steps to restore a sense of mission in Port Arthur. The two shattered battleships, Retvizan and Tsarevich, already under repair, were restored to active service. The Russians began making aggressive patrols outside the harbor and planted new minefields.

Both sides made extensive use of mines during the naval campaign for Port Arthur. Mines had been in use as far back as the American Civil War, but by the turn of the 20th century, their reliability had been greatly improved.

Undetected, the Japanese laid a minefield just outside the harbor and Togo sent cruisers to lure Makarov out on April 12. The Russian took the bait and passed through the minefield without harm but as he returned to port, Admiral Makarov’s flagship, the Petro – pavlovsk, struck a mine that set off its magazines, and another mine heavily damaged the battleship Pobieda. More than 600 Russians died, including Makarov. When word reached Togo of his enemy’s death, Togo, ever the samurai, ordered his men to remove their caps to honor the fallen enemy. Drowning Chinese soldiers could be ignored, but honor must be paid a brave enemy.

The Japanese were also victims of mines. On May 15, two of Togo’s battleships, the Hatsuse and Yashima, were sunk by Russian mines, reducing his battleship force by one-third and mandating a degree of caution on his part. A day earlier, the cruiser Yoshino had been lost to a mine.

For his continuing operations against Port Arthur, Togo operated out of Eliot Island, some 65 miles northeast of the port. Aboard the Mikasa, he received visitors in a spacious but austere cabin. His only comforts were his pipe and a prized set of Zeiss binoculars. The table in front of his desk was covered with maps and charts, but the admiral’s imperturbability was such that some visitors had to remind themselves that Japan was at war.

As the Japanese net around Port Arthur tightened, the czar ordered Admiral Vitgeft, commanding at Port Arthur, to take the remainder of his fleet 1,000 miles north to Vladivostok. He commanded six battleships, three cruisers, and eight destroyers—a fleet that appeared to be at least the equal of Togo’s fleet, diminished as it was by two battleships.

Vitgeft made his move on August 10. Departing at dawn, he set his course south and evaded Togo’s scattered blockaders. But the Russians could steam only at the speed of their slowest ships, and by midday the Japanese had caught up with their foe. The result was a running battle in which, for a time, the decrepit and outgunned Russian ships held their own against the Japanese. The Mikasa absorbed no fewer than 18 hits, three of them from 12-inch shells. Then, abruptly, the battle turned. Several Japanese shells struck the Russian flagship, Tsarevich, killing Vitgeft and most of his staff. The ship’s steering jammed, causing it to go out of control and careen back through the Russian line. The result was chaos, but most of the Russian warships eventually made their way back to Port Arthur.

One of the few criticisms that would be levied against Togo in this instance was that he permitted his enemy to retire in relatively good order. Certainly the Japanese pursuit was uncharacteristically lax. Togo may have been influenced by the need to preserve his remaining battleships, and by the fact that the Russian fleet would be no threat once Port Arthur fell to General Nogi’s infantry. After the Japanese captured 203 Meter Hill, their guns could shell the Russian ships in the harbor. On January 2, 1905, the city trembled from the sound of explosions as the Russians blew up their remaining ships and surrendered. The 11-month campaign had ended in victory for the Japanese.

In St. Petersburg, the court had assumed that the war with Japan would be over in a few weeks. Instead, Japanese troops had laid siege to Port Arthur and had marched into Korea with astonishing speed; by April 1904, they were along the banks of the Yalu. Yet it was not until June, four months after Togo’s surprise attack on Port Arthur, that the czar’s advisers decided to send naval reinforcements to the Far East.

On June 20, the czar presided over a meeting of the Higher Naval Board, staffed in the best Russian tradition by geriatric aristocrats. The lone exception was 53-year-old Vice Adm. Zinovy Petrovich Rozhestvensky, whose organizational skills made him a standout in the czar’s navy. His determination was legendary; he was prepared to carry on his broad shoulders any new burden laid on by his czar, who wanted him to take the Baltic Fleet and relieve Port Arthur.

A tough disciplinarian, Rozhestvensky had been known to fire live ammunition across the bow of even Russian ships that had ignored his signals. In the words of historian Noel F. Busch, “Burly in stature, extravagant in speech, and given to fits of despondency, rage, and sudden euphoria, Rozhestvensky was the mirror opposite of his tiny, taciturn, and phlegmatic adversary.”

Russia’s Baltic Fleet may have appeared to be the equal of anything it was likely to encounter in the Far East, but those appearances were deceptive. The Russian battleships were so top-heavy they were in danger of capsizing in a rough sea, and their secondary armament was all but submerged in heavy weather. And Russian shortcomings went far beyond equipment. The few skilled officers available were spread so thin as to be of little use. And the crews of the Russian fleet consisted largely of peasants, conscripts, and reservists with little training. Not until the fleet was underway was it discovered that crews also included revolutionaries—sailors whom one officer called “slackers and dangerous elements.”

Preparations for the fleet’s departure had taken nearly four months. Because Russia had no bases along Rozhestvensky’s proposed route (which would take his force halfway around the world), the Russians engaged a German firm to station colliers along the way. This arrangement proved one of the few logistical successes of the voyage.

On October 11, 1904, the motley Russian fleet, a total of 42 vessels, steamed slowly out of the Baltic port of Libau on a sevenmonth voyage to disaster. The simplest maneuvers proved a challenge; one battleship ran aground briefly, and another collided with a destroyer. At night Russian searchlights darted over the sea, for there were rumors that the Japanese had torpedo boats in the area. These rumors contributed to Rozhestvensky’s first misfortune. One night off Dogger Bank in the North Sea, Russian lookouts saw vessels. Believing them to be Japanese torpedo boats, the Russians opened fire, sinking a British fishing boat, leaving two dead, and injuring six fishermen, precipitating an international incident. In the chaos, Russians even fired on their own armored cruiser, the Aurora.

An immediate result of the Dogger Bank affair was that the Royal Navy tracked the Russian fleet and sought to harass it in any way it could. The British kept immaculate formation, as if to offer a deliberate contrast with the straggling Russian line. The sight once caused the badly stressed Rozhestvensky to break down. “Those are real seamen,” he sobbed. “If only we…” He broke off, and strode quickly across the bridge.

On December 15, at his last coaling stop in Africa, Rozhestvensky learned that the fall of Port Arthur was imminent. In effect, the fleet that he was being sent to reinforce would soon be captured, and his own voyage was pointless. Alas, the admiral received no new orders from St. Petersburg, and was himself not inclined to turn back. After a year of heavy duty, he ruminated, Togo’s ships must be badly in need of refitting. If the Russians could reach Japanese waters before the enemy fleet was fully restored, they might have a chance.

By Christmas, the Russians reached Madagascar, where Rozhestvensky learned he would be receiving reinforcements. Belatedly reminded that their admiral would have no fleet to greet him at Port Arthur, St. Petersburg was sending him reinforcements: an obsolete battleship, an armored cruiser constructed in 1882, and three 10-year-old coast defense ships of uncertain worth. Rozhestvensky protested in vain that ships so old would prove a liability against the Japanese.

Meanwhile, morale collapsed. The news of Port Arthur’s fall spread quickly through the fleet, and depression combined with a sense of outrage. Russian newspapers told of “Bloody Sunday” in St. Petersburg, when Russian soldiers had killed scores of hungry peasants outside the czar’s palace. Weeks that should have been spent in maneuvers and gunnery training were consumed in basic maintenance and in staving off mutiny. Rozhestvensky attempted to resign and when his offer was refused, took to his cabin with what may have been a nervous breakdown. He cabled St. Petersburg: “I have not the slightest prospect of recovering command of the sea with the force under my orders. The only possible course is to use all force to break through to Vladivostok and from this base to threaten the enemy’s communications.”

As the Russian fleet passed through the Strait of Malacca, Japanese spies in Singapore were unimpressed. The Russian ships were not good at keeping station, the battleships were so heavily laden that their decks were sometimes awash, and the hulls were encrusted with seaweed and barnacles.

Togo’s own fleet, in contrast, was in fighting trim as it waited in the Korean harbor of Masan. A gunnery specialist, Togo regularly exercised his crews at the guns, sometimes attaching a rifle to the 12-inch guns so crews could observe the fall of shot without wasting ammunition. Morale on the Japanese ships was so high as to approach fanaticism.

On May 18, Togo received word that the enemy fleet had left Vietnam on a northerly course. But what would be its route to Vladivostok? While the Strait of Tsushima was the most direct course, Rozhestvensky might choose to steer to the east of the Japanese islands before making for Vladivostok through any of several channels. But then came word that the Russians had diverted all their auxiliaries—storeships, service vessels, and colliers—to Shanghai. That intelligence confirmed that the Russians would take the most direct route, for they could not reach Vladivostok on the eastern course without coaling.

As battle loomed, Togo had four modern battleships; Rozhestvensky had five. But Togo had eight heavy cruisers against his enemy’s three, and an overwhelming superiority in light cruisers and torpedo boats. More important, the Japanese sailors were splendidly trained. Togo had drilled into his men that in battle they should never believe that the Japanese were losing. Damage to one’s own ship was clearly visible, he instructed them, while damage inflicted on the enemy was often out of sight.

A Japanese cruiser first spotted the Russian hospital ship south of Tsushima Island early on the morning of May 27. At Masan, Togo heard with relief that his assumption that the Russians would opt for the Tsushima Strait had been borne out. While his fleet raised steam, additional Japanese cruisers began to shadow the Russian armada, which approached in two parallel lines.

Togo had initially planned to open the battle with his torpedo boats, but the seas proved too heavy. Instead, he led his capital ships out of Masan to a point northeast of Tsushima Island, where he caught his first glimpse of the Russians. The first shots were exchanged at about 11 o’clock in the morning. Togo noted with satisfaction that his enemy was engaged in a clumsy attempt to reform his two columns into a single line. In the best Nelsonian tradition, he ran signal flags up the Mikasa’s mast bearing the message, “The country’s fate depends upon this battle. Let every man do his duty with all his might.”

From a position northeast of the Russian van, Togo led his battle fleet west and then southwest, so that for a time the two fleets were sailing in opposite directions in almost parallel columns. As the Japanese had earlier lain between the enemy and his goal of Vladivostok, the purpose of these maneuvers is unclear. Togo may have been attempting to get to windward of the Russians in order to make more effective use of his optical rangefinders.

To effectively engage, Togo was obliged to make the boldest move in the battle. At 1:40 P.M., he ordered both divisions of his fleet to turn to port, toward the enemy line. Rather than turn simultaneously, each ship was to execute a 180-degree turn in sequence, at the same position, following the Mikasa. The Russians realized that they were being presented with a fixed target, and damaged several of the Japanese warships as they executed their turns. The Mikasa, a gold imperial chrysanthemum adorning its prow, was especially hard hit. A simultaneous turn would have been less risky, but would have placed Togo’s flagship at the rear of his column rather than in the van— hardly the place for a samurai.

Now the Japanese gunners demonstrated their superiority. As the two columns steamed north east, separated by some 4,000 yards, the Russians suffered heavy casualties. An officer aboard the Kniaz Suvorov, Rozhestvensky’s flagship, described the carnage:

Abreast of the foremost funnel arose a gigantic pillar of smoke, water and flame…. The next shell struck the side by the center six-inch turret…. Smoke and fire leapt out of the officers’ gangway; a shell, having fallen into the captain’s cabin, and having penetrated the deck, had burst in the officers’ quarters, setting them on fire.

Rozhestvensky was seriously wounded in the exchange and lost consciousness for a time. As his flagship staggered out of line, the admiral was transferred to a Russian destroyer. His last signal to his second in command, Rear Adm. Nikolai Nebogatoff, was to press on to Vladivostok.

The leading Russian battleships, Suvorov, Aleksandr III, and Borodino, were wrapped in smoke, their crews unable to make out a target, their decks littered with bodies and debris. A fourth vessel, the Osliabia, sank at 3:10 P.M., the first battleship ever sunk by gunfire. The action paused for a time as several Russian ships circled the crippled Suvorov before resuming their course north. Twice Togo was able to cross their line of advance, inflicting heavy advantage in the ultimate naval tactic of “crossing the T.”

In the late afternoon, the Aleksandr III led a straggling line of warships in the direction of Vladivostok, some 400 miles away. Damage to the Japanese had been minimal; only the Mikasa and Asama had been badly battered. For the Russians, the day had been an unrelieved disaster. To cap it, the Aleksandr III capsized at about seven o’clock that evening, and soon after, the Borodino exploded.

With the Japanese penchant for night actions, Togo now unleashed the destroyers and torpedo boats that he had withheld from the battle thus far. Although the Japanese scored relatively few hits, the effect of the night attack was to further disperse the enemy ships and to dishearten the Russian captains.

At daylight on May 28, Togo resumed the attack with his capital ships. He was by then some 150 miles from where the battle had begun. Near the island of Takeshima, Nebogatoff in the Nikolai I found himself under heavy fire and running short of ammunition. After meeting with his officers, Nebogatoff ran up a white tablecloth as a symbol of surrender. According to his staff, Togo was “astonished and somewhat disappointed” that the Russians had not gone down fighting.

Tsushima was the greatest naval battle since Trafalgar, and was even more one-sided. The Japanese had sunk six of 11 Russian battleships and captured four. One was scuttled, and they sank, captured, or drove into port 25 other vessels. Only one Russian cruiser and two destroyers reached Vladivostok. The Japanese lost only three torpedo boats.

In St. Petersburg, a shaken Czar Nicholas realized that the war was lost. He sent his ablest diplomat, Count Sergius Witte, to the United States to discuss President Theodore Roosevelt’s earlier offer to negotiate peace with Japan. Under the terms of the Portsmouth Treaty, signed on September 5, 1905, Japan was awarded the Liaotung Peninsula, including Port Arthur, and the southern half of Sakhalin Island. Russia promised to honor an earlier commitment to evacuate Manchuria, while recognizing Japan’s special interest in Korea.

At a naval hospital at Sasebo, Admiral Rozhestvensky received the best care available. Doctors removed a steel splinter from his skull, and the Russian began a slow recovery. One of his first visitors was Togo, who assured him that no warrior incurred shame from an honorable defeat. In sharp contrast to Japan’s cruel treatment of prisoners in World War II, Russian sailors captured at Tsushima were treated humanely and eventually repatriated.

Once in St. Petersburg, Rozhestvensky was dismissed from the service for “failure to perform his duty,” but this was considered a relatively light sentence. Nebogatoff, his deputy, was shot. Rozhestvensky lived on in obscurity until his death in 1909.

Togo and his army counterpart, Gen. Maresuke Nogi, were national heroes. When Togo took a train from Yokohama to Tokyo to make his personal report to the emperor, cheering crowds lined the track, waving flags. On December 20, Togo was made chief of the Imperial Navy General Staff, in effect the supreme commander of his country’s naval forces. His farewell speech to his fleet included a line that tells much of his success: “The gods award the crown to those who, by their training in peacetime, are victorious even before they go into battle.”

Togo’s victories were noted in Europe, especially in Great Britain. The evaluation of how important battleship speed and training in gunnery had been in the one-sided victory contributed to the decision by British officials to begin developing the Dreadnought-class of big-gun warships. Togo’s husbanding his strength until presented with the opportunity to crush his enemy at Tsushima reminded all navy men of the virtues of tactical caution.

Togo became a roving ambassador for the new Japan. In 1911, he and General Nogi represented their country at the coronation of King George V of Great Britain. On his way home, Togo called on President William H. Taft and former president Theodore Roosevelt, who had helped bring the Russo-Japanese War to a close.

Although virtually retired, Togo was named fleet admiral in 1913. A year later, he became mentor to the 11-year-old crown prince, who would later become Emperor Hirohito. Among the prince’s advisers, Togo is known to have favored the concept of imperial absolutism against those who sought to limit the emperor’s power. He undoubtedly transmitted to the crown prince his own concepts of honor and duty. We can infer also that Togo passed on to his protégé the lesson of the war with Russia: the importance of committing a large, well-prepared fleet, without worrying unduly about such diplomatic niceties as a declaration of war.

Although Togo had employed neither aircraft nor submarines at Tsushima, he also later became a strong advocate of submarines and of creating a naval air force.

In the 1920s, Togo became politically allied with the ultranationalist right. Along with other senior officers, he opposed the Five-Power Naval Limitation Treaty of 1922, which restricted the size of the Japanese navy relative to those of the United States and European powers. He took no part in the political upheavals of the early 1930s, but did nothing to discourage Japan’s growing xenophobia.

In the spring of 1934, Togo was found to be suffering from cancer. On May 28, the anniversary of Tsushima, the emperor awarded him the rank of marquis. Because he was too weak to attend a ceremony at the palace, Togo had his full dress uniform laid out across his bed. He died two days later.

In fighting Russia, Japan gambled that a surprise attack, before Russia was prepared, would allow Japan to seize control of the sea while the army moved on its land objectives. Togo and Nogi played their roles to perfection.

In 1941, Japan’s strategy would be similar: Destroy the U.S. fleet at Pearl Harbor, then control the Pacific long enough to acquire the natural resources, especially oil, that would allow it to win a war of attrition. Fittingly, the lead carrier Akagi in the attack on Pearl Harbor flew the battle flag that Togo had flown on the Mikasa in his surprise attack on Port Arthur. Confronting the United States, however, would prove very different from dealing with Czar Nicholas II’s decrepit navy.

After World War II, Togo’s reputation went into eclipse, a victim of Japan’s revulsion against all things military. Schoolbooks no longer exalted his name, and the anniversaries of his birth and death went unmarked. At the end of the 1980s, however, Togo’s reputation was rehabilitated, and a statue of him was raised near his birthplace in Satsuma.

Togo was without question a brave and skillful sailor. The path on which he led his country, however, would eventually lead to crushing military defeat, and repudiation of the Bushido code by which he had lived.

Originally published in the Winter 2009 issue of Military History Quarterly. To subscribe, click here.