In 1905 a Japanese admiral who fancied himself the reincarnation of Horatio Nelson waged a battle for the ages against a Russian fleet at Tsushima Strait

On the night of May 26–27, 1905, two battle fleets—one Russian, the other Japanese—sailed toward the Tsushima Strait, the eastern channel of the Korea Strait between that nation and Japan. The Russian commander, Vice Adm. Zinovy Rozhestvensky, desperately wanted to avoid contact and take his ships safely into Vladivostok, his nation’s primary naval port in the Pacific. His Japanese counterpart, Adm. Heihachiro Togo, was determined to locate, engage and destroy the Russian fleet and thus effectively end the Russo-Japanese War in his country’s favor.

Rozhestvensky’s hopes to evade a fight were soon shattered. The ensuing clash—the first between fleets of modern steel battleships—was to be as much of a defining moment in naval, political and diplomatic history in the 20th century as the Battle of Trafalgar had been a century earlier. By the time the smoke cleared, imperial Russia had involuntarily ceded both its naval dominance and considerable political influence in the Far East to a newly resurgent and expansionist imperial Japan.

The February 1904 to September 1905 Russo-Japanese War centered on rival expansionist ambitions, erupting over which nation would dominate Manchuria and Korea. Russia was desperate to acquire a warm-water port of its own in the Pacific, while Japan wanted to expand its sphere of influence north of its home islands.

Negotiations between the two nations—which proposed Russian control of Manchuria and Japanese hegemony over Korea—ultimately collapsed, sparking the first major war of the 20th century. Hostilities commenced when the Japanese made a surprise attack on, sought to blockade and then laid siege to the Russian base at Port Arthur, on the Liaodong Peninsula. Subsequent naval clashes—all won by Japan—culminated in the Aug. 10, 1904, Battle of the Yellow Sea, a strategic victory for Japan, albeit tactically inconclusive.

Russia’s Pacific Fleet was much diminished by that battle and the ongoing siege of Port Arthur. Were it to remain in the war, it would need reinforcement. Czar Nicholas II and his advisers resolved to send much of the Baltic Fleet (subsequently designated the Second Pacific Squadron) to the Far East. Rozhestvensky, the man tapped to command the flotilla, was a highly regarded veteran of the 1877–78 Russo-Turkish War and former chief of the imperial Russian naval staff. He was also known for a fiery temper that terrified subordinates.

Unfortunately, the chaotic, seven-month-long voyage to the Far East only served to spotlight Russian inefficiency. While transiting the North Sea’s Dogger Bank one foggy night that October the squadron passed among British fishing vessels, which spotters mistakenly identified as Japanese torpedo boats. The Russians opened fire, sinking one trawler, damaging four others, killing two fishermen, wounding a half dozen others and in the process almost sparking war with Britain. Further confusion followed when the warships fired on one another, inflicting further casualties and damage.

By the time the squadron reached the Far East the following spring, it was in a pitiable state and certainly not battle ready. The majority of its 11 battleships, eight cruisers, support ships and auxiliaries had steamed 18,000 nautical miles via the Cape of Good Hope and Cam Ranh Bay in French Indochina (present-day Vietnam) and needed extensive refitting. The voyage had also proved hard on crewmen, leaving them weary and demoralized. More important, only four of the Russian battleships were of the latest Borodino-class type, based on a successful French design. And even those vessels—Borodino, Knyaz Suvarov, Oryol and Imperator Aleksandr III—were not ready to fight at full capability, as they were manned by new, ill-trained crews. The remaining seven battleships were older and less technically advanced.

Unfortunately for the Russians, their opponents would bring to the fight both better vessels and a far more competent commander.

On emerging from its self-imposed isolation in the mid-19th century, Japan had embarked on a rapid modernization of its military forces. Part of that effort was the development of a modern battle fleet based on the doctrines of American historian, naval officer and strategist Alfred Thayer Mahan. The sole object of Mahan’s tenets was starkly simple—command of the sea through the neutralization or destruction of the enemy fleet.

Japan set about building a modern blue-water fleet from the ground up, basing it on mostly up-to-date vessels built either in British yards or locally to British specs. The new-build ships were fitted with technologically advanced guns, ammunition, range finders, radios and other equipment. Their mostly British-trained crews were disciplined, competent and highly motivated. By the time the Russian squadron arrived in the Pacific, the Combined Fleet of the Imperial Japanese Navy boasted five modern battleships, 27 cruisers, 21 destroyers and a few dozen torpedo boats.

Just as important for Japan was the man who would command the fleet in action against the Russians. Fifty-six years old at the outbreak of the Russo-Japanese War, Adm. Heihachiro Togo had spent many of his formative professional years with the British Royal Navy. That time included academic work, time at sea aboard various warships and work as an inspector during the construction of one of three battleships being built for Japan in British yards. As a result of his seven years in Britain, Togo acquired much of the culture and professionalism of the Royal Navy and eventually saw himself following in the wake of his naval hero, Adm. Horatio Nelson. Togo commanded the cruiser Naniwa at the Battle of the Yalu River amid the 1894–95 First Sino-Japanese War. He later served as commandant of the Naval War College in Tokyo and in 1903 was named commander in chief of the Combined Fleet. The following year Togo led the fleet into battle against the Russians at Port Arthur and the Yellow Sea, in each of which he demonstrated an innate grasp of modern naval warfare.

It was a talent he would soon reveal to his Russian counterpart.

As he approached Tsushima, Rozhestvensky hoped to take advantage of the thick fog the Russian vessels encountered to evade the Japanese and slip into the harbor at Vladivostok undetected. It proved a vain hope, however. The patrolling Japanese auxiliary cruiser Shinano Maru caught sight of the navigation lights of the hospital ship Oryol, at the rear of the Russian line, and subsequently identified the profiles of the Russian warships through the gloom. The cruiser’s captain radioed the enemy’s position to Togo, who sailed to intercept the Russians. It marked the first time wireless signals were used operationally by underway warships.

“When the enemy’s fleet first appeared in the south seas, our squadrons, in obedience to imperial command, adopted the strategy of awaiting him and striking him in our home waters,” Togo later wrote. “We therefore concentrated our strength at the Korean straits.” Continuous radio reports from Shinano Maru guided the larger Japanese fleet toward the Russians, and at daylight the fog dispersed, allowing 5 miles of visibility. By early afternoon on the 27th both fleets could see each other.

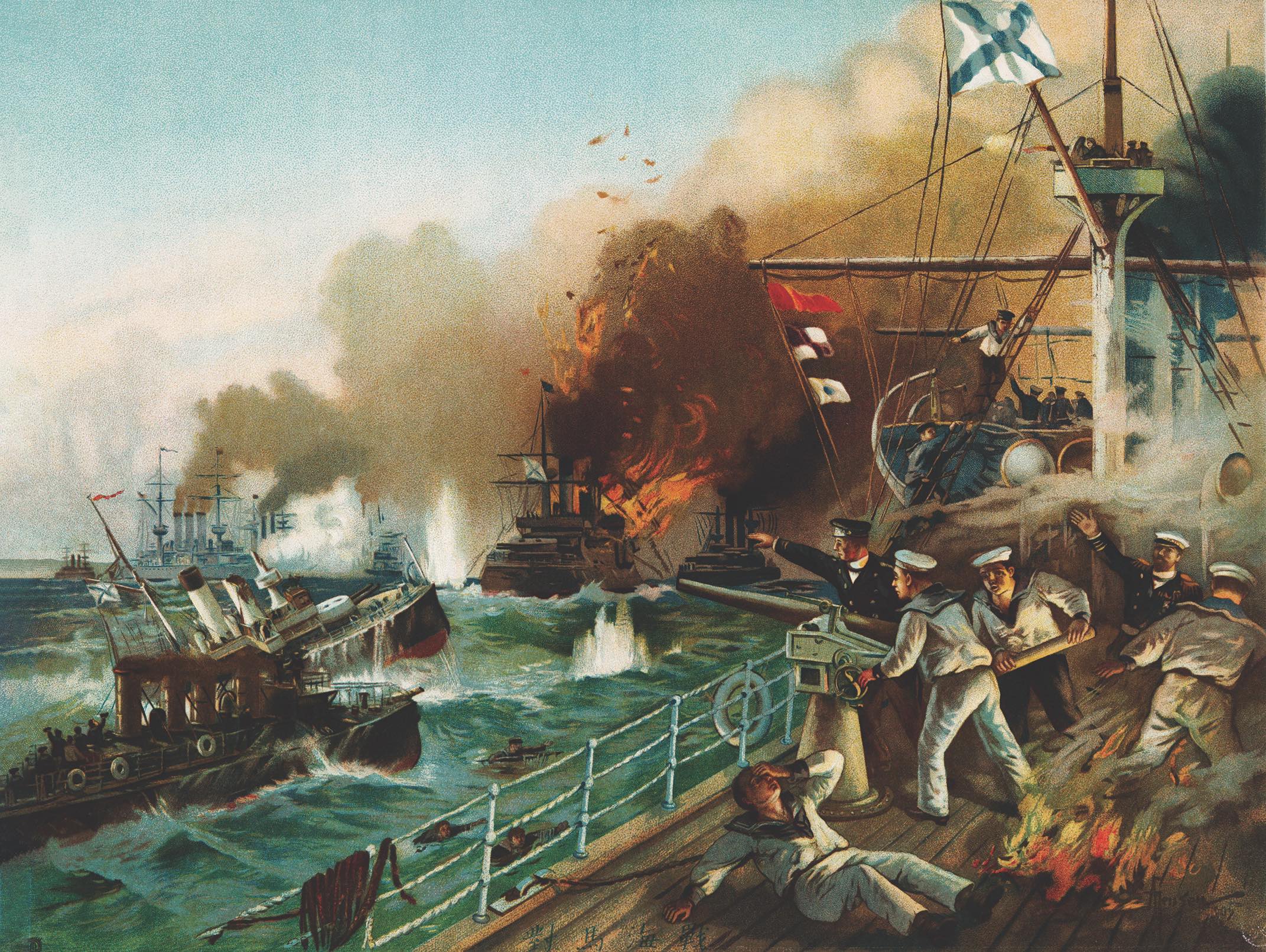

On closing with the enemy, Togo carried out the classic naval maneuver known as “crossing the T,” taking his ships in line astern across the front of the Russian formation at a range of 7,500 yards. This allowed the main armament of each Japanese ship to bear on the van of the Russian line, while Rozhestvensky’s vessels were only able to deploy their forward guns. The Japanese tactic, combined with their better gunnery knowledge and technique, gave Togo’s gunners the ability to hit their targets more accurately and at longer ranges than could their adversaries. As firing was about to begin, Togo sent a signal reminiscent of Nelson at Trafalgar: “The fate of the empire depends on the result of this battle—let every man do his utmost.”

At an initial disadvantage because of his flotilla’s line-astern formation and the need to protect his slow and cumbersome supply ships, Rozhestvensky was eventually able to turn his squadron into a line of battle parallel to the Japanese, allowing most of his ships’ guns to fire at the enemy. By then the Japanese were focusing their fire on Knyaz Suvorov, the Russian flagship, which was hit repeatedly and sank after attempting to withdraw. The battleship Oslyabya suffered the same fate. Rozhestvensky, injured by shrapnel aboard Knyaz Suvorov, transferred to the destroyer Buinyi and handed over command of the squadron to Rear Adm. Nikolai Nebogatov, aboard the battleship Imperator Nikolai I.

The change of leadership did little to alter the course of the battle. The Japanese ships were equipped with the latest British-made Barr & Stroud gunnery range finders, which had a greater range and enabled a higher rate of fire and far better accuracy than the Russians’ sighting equipment, which mostly dated from the 1880s. As the battle raged on, the Russian battleships Borodino and Imperator Aleksandr III were repeatedly struck and severely damaged, causing them to fall out of the line of battle and eventually sink.

“It seemed impossible even to count the number of projectiles striking us,” recalled Capt. Vladimir Semenoff of Knyaz Suvarov. “I had not only never witnessed such a fire before, but I had never imagined anything like it. Shells seemed to be pouring upon us incessantly, one after another.…The steel plates and superstructure on the upper decks were torn to pieces, and the splinters caused many casualties. Iron ladders were crumpled up into rings, and guns were literally hurled from their mountings.…In addition to this, there was the unusual high temperature and liquid flame of the explosion, which seemed to spread over everything. I actually watched a steel plate catch fire from a burst.”

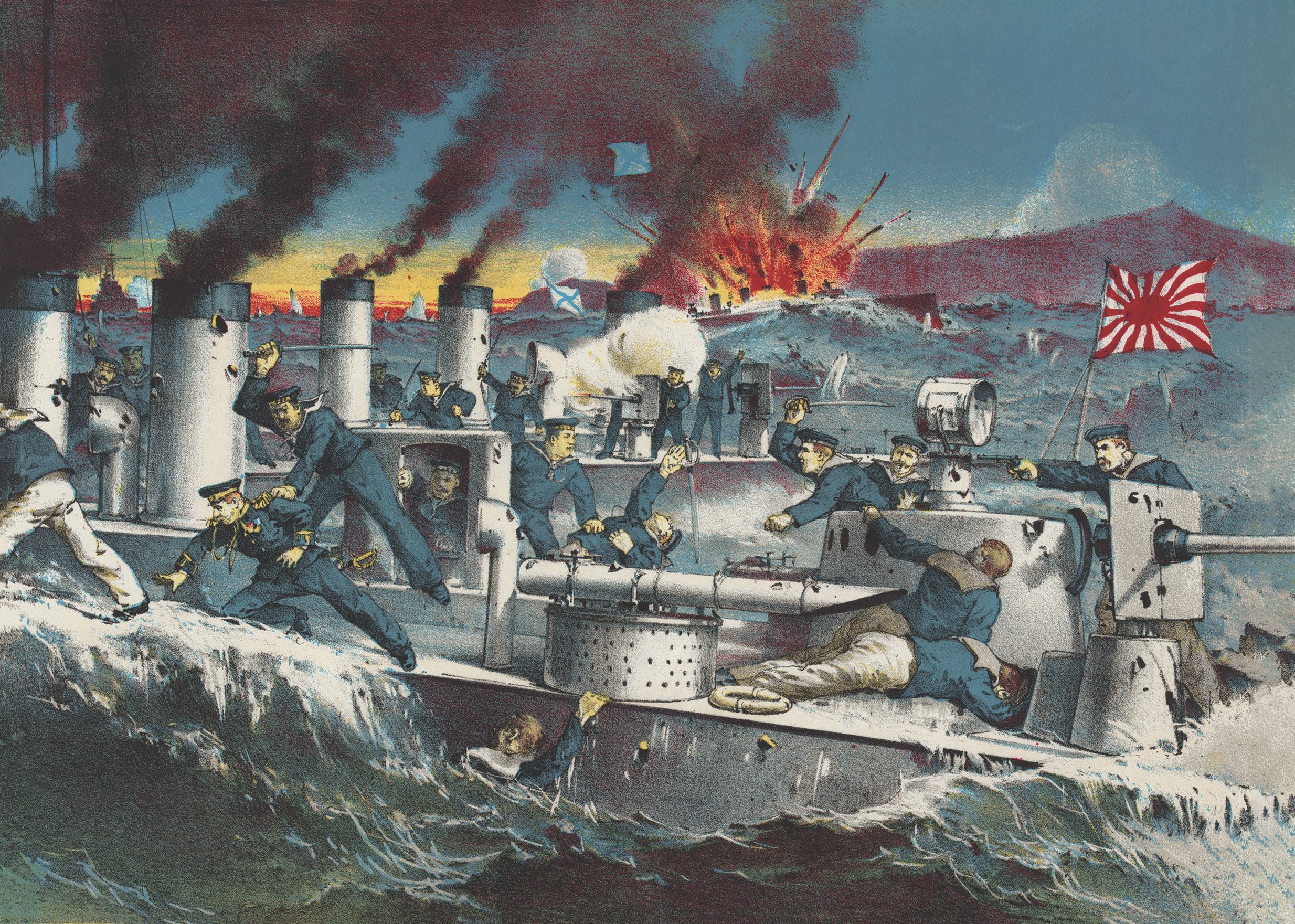

The main engagement between the Russian and Japanese fleets was largely over by sunset, the former losing four battleships sunk and others badly damaged. The Japanese suffered no serious losses. With the coming of darkness, most of the surviving Russian warships desperately steamed toward Vladivostok. But Togo was not done with them yet—he ordered his numerous destroyers and torpedo boats to continue the attack.

In those days before radar there was inevitably little cohesion or coordination in either fleet, and the night attacks quickly became a chaotic series of ship-on-ship skirmishes. Several Japanese vessels collided with each other, and some Russian ships added to their own misery by switching on searchlights to spot their attackers. This only served to reveal their own positions, making them easy targets for Japanese torpedo attacks. By morning the Russians had lost two more battleships and two armored cruisers against the loss of just three Japanese torpedo boats. Russian losses included the battleship Navarin. Left dead in the water by a mine strike, it was hit by four torpedoes, capsized and sank. Only three of its nearly 700-man crew lived to tell the tale.

The battleship Sissoi Veliky, already ablaze from the gunnery exchange between the battle fleets, sustained a torpedo hit that damaged its screws and rudder. An attempt to beach the foundering vessel near Tsushima Island was foiled by the arrival of two Japanese cruisers, prompting the Russian captain to surrender his ship, which promptly sank. The armored cruiser Vladimir Monomakh likewise fell victim to Japanese torpedoes, while a Japanese destroyer collided with the armored cruiser Admiral Kakhimov. The captains of both crippled warships ordered them scuttled after dawn.

Meanwhile, Nebogatov continued north toward Vladivostok with six of the remaining ships, but Togo caught them off the east coast of Korea near Takeshima Island. Realizing further fighting was futile in the face of the now overwhelming Japanese force, Nebogatov surrendered. Refusing the order, the captain of the cruiser Izumrud fled with his ship, though the vessel later ran aground off the Siberian coast, and the captain ordered it scuttled.

Of the other scattered Russian vessels that had no part in the surrender, most were caught and sunk by the Japanese. However, three warships did manage to reach Vladivostok, and a few others—including the cruiser Aurora—were interned in neutral ports.

The crushing Russian defeat at Tsushima prompted the government of Czar Nicholas II—justifiably fearful of revolution amid the unpopularity of the war and increasing unrest on the home front—to sue for peace. Their economy gravely strained by the conflict, the Japanese were themselves ready to end hostilities. Accordingly, Tokyo requested the help of U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt, who was asked to arrange a peace conference. The event was held at the Portsmouth Naval Shipyard in Kittery, Maine, and resulted in the September 1905 Treaty of Portsmouth, ending the war. The international community recognized Roosevelt’s role in bringing about a negotiated peace, and he was awarded a Nobel Peace Prize in 1906.

Togo had a quite different take on the battle, afterward writing in his diary, “I am firmly convinced that I am the reincarnation of Horatio Nelson.”

As noted in the British Admiralty’s confidential staff history of the Russo-Japanese War, written in 1915 by prominent British naval historian and strategist Sir Julian Corbett, the Battle of Tsushima established Japan as both a major naval power and the foremost nation in the Far East. It also helped foster Tokyo’s expansionist aspirations. “So was consummated perhaps the most decisive and complete naval victory in history,” Corbett wrote. “No major Japanese unit had been seriously damaged, and only three torpedo boats sunk. One hundred seventeen Japanese officers and men had been killed, and 583 wounded. On the Russian side 12 major units, four destroyers and three auxiliaries had been sunk or scuttled after being disabled, and four major units and a destroyer captured. Of all Rozhestvensky’s motley but imposing array, only one armed yacht and two destroyers got through to Vladivostok. The toll in casualties was terrible, in the worst Russian tradition: 4,830 killed, 5,907 prisoners, 1,862 interned.…Not in [Britain’s] most successful war had we obtained a command of the sea so nearly absolute as that which Japan now enjoys.”

The Battle of Tsushima had lasting ramifications. Expressed through its naval prowess, Japan saw itself as one of the world’s front-rank nations and the leading nation in East Asia. Tokyo gained international recognition as having the world’s sixth most powerful navy. That navy’s successes in the Russo-Japanese War, coupled with the successes of Japan’s army ashore, fostered a widespread belief among the Japanese in their country’s superiority. That perception likely contributed to Japan’s unrestrained and violent behavior in China in the 1930s and ultimately to the 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor.

The negative impact of the battle on imperial Russia was equally significant. Having forfeited its naval strength in the Far East, it suffered a huge loss of face in both Asia and Europe. Among its potential enemies, Austria-Hungary and Germany were particularly emboldened. Moreover, the defeat helped foster unrest within the Russian navy, which resulted in mutinies at Sevastopol, Vladivostok and Kronstadt and the 1905 Potemkin uprising. These, in turn, were background factors to the 1917 revolutions and subsequent civil war in Russia.

As Israeli historian Rotem Kowner points out in his 2006 book The Impact of the Russo-Japanese War, Tsushima substantiated Mahan’s arguments about the decisive importance of the battleship. It validated the supremacy of firepower and speed, influencing warship design and providing the impetus for British First Sea Lord Adm. John “Jacky” Fisher’s HMS Dreadnought. On its commissioning in 1906, that first all-big-gun battleship immediately rendered existing warships obsolete.

An extraordinary footnote to Tsushima is that two of the ships that squared off in battle nearly 125 years ago have been preserved and are open to the public. Both Togo’s flagship, the battleship Mikasa, in Yokosuka, and the Russian cruiser Aurora, in St. Petersburg, are museum ships. Aurora has a further and more symbolic claim to fame—or perhaps notoriety—as the ship that in 1917 fired its forecastle gun within hearing of the Winter Palace in St. Petersburg, signaling the start of the October Revolution. MH

Alan George is a British journalist, historian and former U.K. Ministry of Defence press officer who sailed with the task force that recaptured the Falkland Islands from Argentina in 1982. For further reading he recommends Big Fleet Actions, by Eric Grove; The Battle of Tsushima, by Capt. Vladimir Semenoff; and Maritime Operations in the Russo-Japanese War, 1904–1905, by Julian S. Corbett.

This article appeared in the January 2022 issue of Military History magazine. For more stories, subscribe and visit us on Facebook.