In late 1862, while suffering through continuing Union military disasters, handling a contentious cabinet and wrestling with the Emancipation Proclamation, President Abraham Lincoln had to agonize over another matter. He had to decide whether to allow the execution of more than 300 Indians convicted of war crimes in Minnesota’s Great Sioux Uprising. One of the first and bloodiest Indian wars on the western frontier, the Great Sioux Uprising (today called the “Dakota-U.S. Conflict) cost the lives of hundreds of Native Americans, white settlers, and soldiers. After the U.S. Army suppressed the uprising it established a commission that condemned 303 Dakota men in trials that were patently unfair. Federal law, however, required the president’s approval of the death sentences. “Anxious to not act with so much clemency as to encourage another outbreak on the one hand, nor with so much severity as to be real cruelty on the other, Lincoln ignored the howling of a white populace thirsting for revenge and began the arduous task of reviewing the trial records and deciding the fates of hundreds of men.

The Dakota had existed for generations on the land surrounding the confluence of the Mississippi and Minnesota Rivers, site of the present-day cities of Minneapolis and St. Paul. Translated roughly into English, Dakota means “the allies, and they were a group of seven Indian bands that lived mostly in harmony in the region’s bountiful river valleys. Their only enemy was the Chippewa to the north. The first European explorers there had done little to alter the Indians’ way of life, although the French dubbed them the Sioux—a mutation of the Chippewa word for “snake. Real change began after 1819, when federal soldiers built Fort Snelling, a sprawling outpost above the mouth of the Minnesota River. After that the stream of white traders and settlers became a flood; land treaties in 1837 and 1851 and Minnesota statehood in 1858 pushed the Dakota off their native lands westward to a narrow, 100-mile-long reservation on the harsh prairie along the Minnesota River. The exodus also forced the Dakota to change their way of life. Government agents on the reservation favored those Dakota who settled on plots, learned English, cut their hair, and took up farming. Yet the crops failed year after year, and the Dakota grew dependent upon government gold annuities that were promised by the land treaties, and upon the foods and sundries peddled by white traders. The Dakota were often left with little after government agents paid annuity moneys first to the traders who had given credit to the Dakota for goods purchased at highly over-inflated prices. Those Dakota who refused to give up their traditional ways were in an even worse position and spent many winters in near-starving conditions.

The situation reached its flashpoint in the summer of 1862. The financial cost of the Civil War was bleeding the government dry, and rumors flew that there would be no annuity gold for the Dakota. Traders who had liberally given credit in the past now slammed the door. One trader named Andrew Myrick announced that if the Dakota were hungry they could “eat grass. Tensions mounted until four Dakota led by an Indian named Killing Ghost murdered five white settlers on August 17. Some Dakota leaders sensed this was an opportunity to strike back at the U.S. Government, and they pressed Chief Taoyateduta, or Little Crow, to strike at the whites while many soldiers were fighting in the Civil War. Little Crow initially wanted no part of a war with the whites, recognizing the calamity that would surely follow. But when faced with a challenge to his authority, he reluctantly relented. Ironically, the annuity gold shipment had left St. Paul that same day.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our Historynet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Wednesday.

The Dakota raged across the countryside with a fury. Four to eight hundred white settlers were butchered during the first four days of the rampage, while their farms and fields burned. The Dakota hit first and hard at the reservation agency, killing dozens. One of the victims was trader Myrick. His killers stuffed his mouth with grass. The Dakota also struck at the region’s army outpost and towns. They annihilated a detachment of soldiers dispatched from nearby Fort Ridgely before being repulsed in two assaults on the garrison itself. They twice attacked and burned most of the town of New Ulm but failed to capture it from its armed residents.

Panic surged throughout Minnesota. Tens of thousands of terrified settlers fled and virtually depopulated the state’s western regions. Governor Alexander Ramsey dispatched 1,200 men from Fort Snelling under the command of Henry H. Sibley, a former fur trader, politician and friend of the Dakota. Sibley was not regular army, but he heeded Ramsey’s call and accepted a commission as colonel. Unsure of his authority, Sibley failed to declare martial law and moved excruciatingly slowly. He did not engage the Dakota until early September 1862, when Indians surprised and butchered a 150-man reconnaissance detail at Birch Coulee. The debacle slowed Sibley even more, and he did not meet Little Crow in full force until September 22, when he won a decisive victory at Wood Lake. The Dakota scattered over the prairie. Sibley finally managed to capture about 1,200 men, women, and children, but Little Crow was not among them. Sibley intended to prosecute as war criminals those Indians who had participated in the rebellion.

Sibley ordered a commission of five military officers to try the prisoners summarily and “pass judgment upon them, if found guilty of murders or other outrages upon the Whites, during the present State of hostilities of the Indians. Major General John Pope, recently banished to Minnesota by President Lincoln after Pope’s humiliating defeat at the Civil War’s Battle of Second Bull Run, saw an opportunity to redeem himself at the Dakota’s expense. He immediately approved Sibley’s plans. “The horrible massacres of women and children and the outrageous abuse of female prisoners, still alive, call for punishment far beyond human power to inflict, Pope wrote. “It is my purpose utterly to exterminate the Sioux if I have the power to do so… They are to be treated as maniacs and wild beasts.

The commission began the hearings on the reservation on September 28 and tried 16 men that day alone. This breakneck pace continued, and by November 3—a mere five weeks later—the commission had conducted 392 trials, including an astonishing 40 in one day. Observer Reverend J.P. Williamson noted that the trials took less time than the state courts required to try a single murder defendant. The accused were hauled before the commission, sometimes manacled together in groups, and were arraigned through an interpreter. The charges ranged from rape to murder to theft, although most Dakota were accused of merely participating in battles. The defendants entered a plea, and those who pleaded not guilty had an opportunity to speak. The commission then called and examined its own witnesses, but it did not permit the Dakota to have counsel for their defense. As one man who assisted in gathering evidence against the Indians noted, “[T]he plan was adopted to subject all the grown men, with a few exceptions to an investigation of the commission, trusting that the innocent would make their innocence appear.

The commission received testimony from eyewitnesses to some of the murders. Most of the evidence turned out to be hearsay, with witnesses declaring what they heard others say about particular killings. Some witnesses said they merely saw a defendant “whooping around or bragging about killings. The commission relied heavily on six witnesses, each of whom offered evidence in dozens of trials. The most damning of these was Joseph Godfrey, a mulatto who had lived among the Dakota and taken a Dakota wife. He was one of the first tried and convicted of engaging extensively in “massacres, but the commission, impressed with Godfrey’s courtroom presence, recommended imprisonment instead of hanging because he was willing to testify against other defendants. The court reporter noted that Godfrey’s “observation and memory were remarkable. Not the least thing had escaped his eye or ear. Such an Indian had a double-barreled gun, another a single-barreled, another a long one, another a lance, and another one nothing at all… Godfrey testified in more than 50 trials. In a remarkable irregularity the commission even allowed him to question particular witnesses. The Dakota quickly dubbed him Otakle, or “One Who Kills Many. Most defendants admitted to participating in some sort of warfare, whether in battles, attacks on armed settlements, or skirmishes with settlers. After news of the first few death sentences spread among the prisoners, however, many defendants then claimed they did not shoot at settlers or soldiers, or they did not hit them because of poor aim, or their weapons did not fire. Some testified they merely watched others fight or commit atrocities. Others offered evidence that they had saved the lives of whites, but the commission largely ignored it, even when the accounts were corroborated.

Recommended for you

Sibley and Pope desperately wanted to begin the executions immediately, but the sentences required presidential review. On November 7 Pope telegraphed the names of the condemned to Lincoln, at a cost of $400. The editors of the New York Times berated Pope for his profligacy and suggested the amount be deducted from his salary.

Lincoln responded three days later, asking Pope to send “the full and complete record of these convictions” and to identify “the more guilty and influential of the culprits.” Lincoln pointedly added, “Send all by mail.” Pope grudgingly complied but said, “The only distinction between the culprits is as to which of them murdered most people or violated most young girls. All of them are guilty of these things in more or less degree.

Pope’s opinions were only the tip of the iceberg. As Lincoln began his deliberations, people on both sides of the issue bombarded him with letters and telegrams. Politicians, army officers, and clergy called on the president at the White House, each adding his take on the situation and offering advice. Lincoln dutifully and patiently listened. One of his own secretaries, John Nicolay, had been in Minnesota at the time of the conflict, and he told Lincoln that from “the days of King Philip to the time of Black Hawk, there has hardly been an outbreak so treacherous, so sudden, so bitter, and so bloody, as that which filled the State of Minnesota with sorrow and lamentation . . . .” Nicolay’s words must have struck a chord with Lincoln, for the president had been a militia volunteer during the 1832 Black Hawk War in Illinois and Wisconsin.

Governor Ramsey telegrammed Lincoln, “It would be wrong upon principle and policy” to refuse the executions. “Private revenge would on all this border take the place of official judgment of these Indians.” Two congressmen and a senator from Minnesota warned Lincoln that, should he grant clemency, “the outraged people of Minnesota will dispose of these wretches without law. These two peoples cannot live together.” A “resolution” from St. Paul residents declared, “The blood of hundreds of our murdered fellow citizens cries from the ground for vengeance . . . . The Indian’s nature can no more be trusted than the wolf’s.” Pope chimed in again as well, warning Lincoln that the “indiscriminate massacre” of all Dakota would occur if the president was too lenient. One man stood almost alone with a voice of moderation.

Bishop Henry Whipple, head of the Minnesota Episcopal Church, spoke often of the hypocrisy of federal Indian policies. In a newspaper editorial he wrote, “[I]f . . . vengeance is to be more than a savage thirst for blood, we must examine the causes which have brought this bloodshed . . . . Who is guilty of the causes which desolated our border? At whose door is the blood of these innocent victims? I believe that God will hold the Nation guilty.” Whipple was a cousin to Henry Halleck, Lincoln’s general-in-chief, so the bishop gained an audience with the president in November and urged clemency. Lincoln was impressed. “He came here the other day,” Lincoln said later, “and talked with me about the rascality of this Indian business, until I felt it down to my boots.

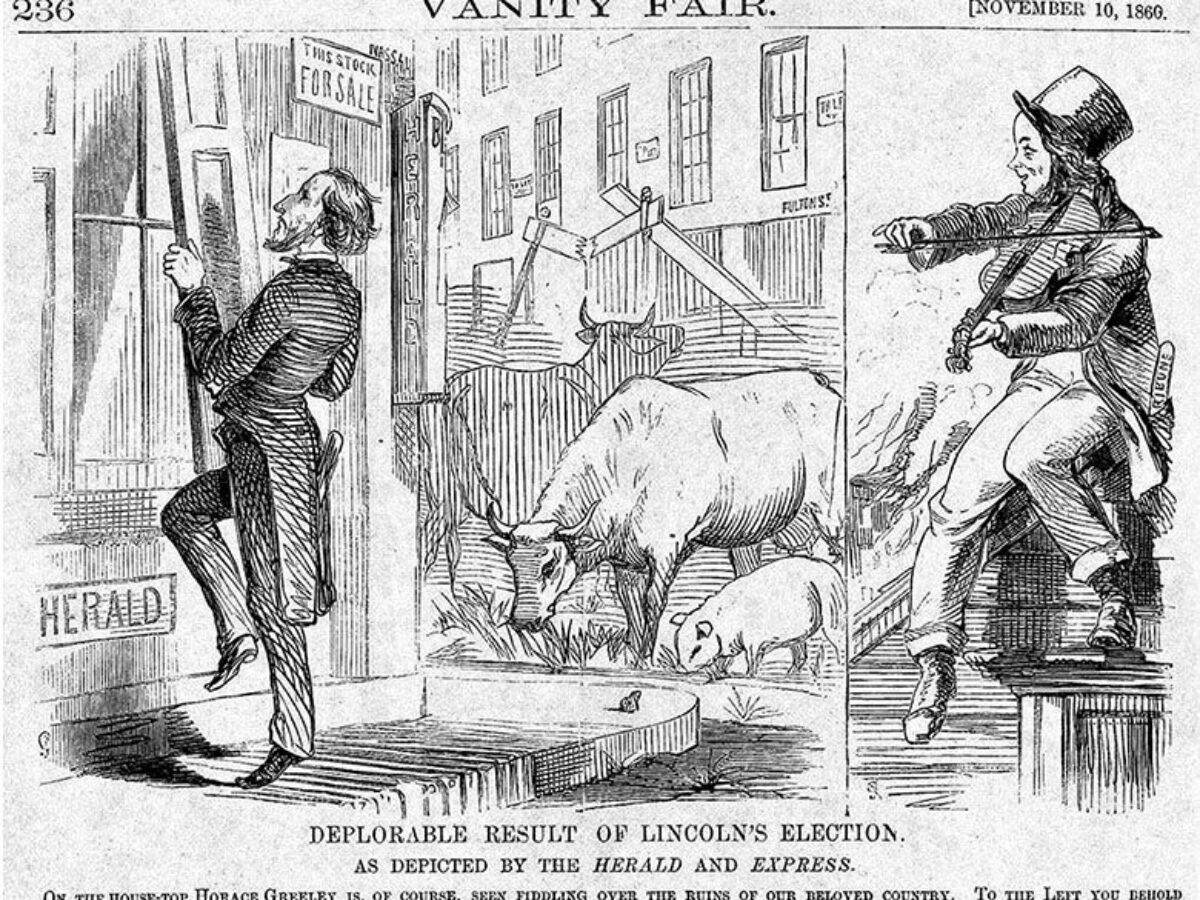

The timing of the Dakota crisis could not have been worse for the president. On a personal level, he and his wife, Mary, still grieved over the death, nine months earlier, of their 11-year-old son, Willie. On a political level, the administration faced one crisis after another. The war effort was in tatters. Major General George McClellan’s Army of the Potomac lay no closer to Richmond after the ill-conceived Peninsula Campaign and the bloody draw at Antietam. McClellan tolerated precious little advice from the president and sometimes even refused to meet with him. Finally the exasperated president dismissed the insolent general and replaced him with Ambrose Burnside, soon to be responsible for the Union disaster at Fredericksburg. As the blunders mounted, Lincoln also faced a challenge to his leadership from disgruntled cabinet members. Treasury Secretary Salmon Chase, perpetually jealous of Lincoln and furious that the president did not turn to him for military advice, sulked and plotted behind the president’s back. Lincoln knew of these designs and only tolerated them because Chase was a supremely able leader of his department.

Slavery issues preoccupied Lincoln as well. Somewhere between the bad tidings and bouts of depression the president managed to work on the final drafts of the Emancipation Proclamation, an executive order that would free the slaves in most of the South, even as he was being called upon to suppress the Dakota. The Minnesota business weighed heavily on Lincoln’s mind.

“Three hundred Indians have been sentenced to death in Minnesota by a Military Commission, and execution only awaits my action,” he wrote to Judge Advocate General Joseph Holt. “I wish your legal opinion whether if I should conclude to execute only a part of them, I must myself designate which, or could I leave the designation to some officer on the ground?” Holt answered, “I am quite sure the power cannot be delegated.” So Lincoln began reviewing the trials. The president first reviewed them as the expert lawyer he truly was. His political fortunes had often risen and fallen, but Lincoln’s brilliant legal career had remained a constant. Largely self-taught, he gained a formidable reputation as both a defense lawyer and court-appointed prosecutor known for his piercing cross-examinations and folksy, countrified manner. He continually asserted he was “not an accomplished lawyer,” but Lincoln appeared before the Illinois Supreme Court more than 200 times and made a small fortune as one of the principal lawyers for the Illinois Central Railroad. The president often utilized his legal skills when called upon to review the hundreds of Civil War military court verdicts appealed to him. By law and practice, there were basically two types of military courts at the time: courts martial and military commissions. Courts martial were comprised of a dozen officers and were generally held to try officers and enlisted men for dereliction of duty—sleeping while on sentry duty, cowardice, desertion, conduct unbecoming an officer—and for crimes such as rape and murder. Military commissions usually consisted of less than a dozen officers and were convened in areas where martial law had been declared, to try civilians accused of military crimes—spying, smuggling, conducting guerrilla actions against Union troops, and recruiting for the Confederacy.

The law allowed the convicted to appeal to Lincoln in most cases, and in capital cases it was a matter of right. In the midst of the havoc wrought by the war, Lincoln spent many hours of many days reviewing transcripts and receiving visits from the pleading family members of convicted men. Lincoln could easily see the defects of the Dakota trials.

Most importantly, the Dakota defendants had not been allowed representation by counsel. Defense lawyers would have raised objections to the jurisdiction of the commission in an area where martial law had not been ordered, as required by law. They would have questioned the impartiality of the five officers on the commission, all of whom fought against the Dakota and undoubtedly harbored ill will toward them. Defense lawyers would have cross-examined the commission’s witnesses, pointing out inconsistencies in their testimony and exposing their biases, particularly those—such as Godfrey—who “turned government’s evidence” and likely testified falsely in attempts to curry favor with the commission and save their necks. Without counsel, the defendants— already trapped behind a language and cultural barrier—did not have anyone to help them understand the proceedings, offer credible mitigating evidence, or develop and practice their own testimonies.

The president could also see how the trials’ rapidity prevented a full and fair analysis of the facts. The weight and impact of evidence simply could not be properly processed in a few minutes, especially in capital cases with their ultimate stakes. Undoubtedly the brevity of the trials resulted from the absence of defense counsel. The president could also see how the commission convicted many men with insufficient evidence. Lincoln, a master politician, also reviewed trials with a political perspective. On December 1 he gave the requisite nod to those who had pressured him against clemency by telling Congress, “The State of Minnesota has suffered great injury from this Indian war.” While he did not tip his hand about his imminent decision, it was a signal he would offer some satisfaction there. Yet he also knew how the rest of the world, especially Britain—still considering whether to recognize the Confederacy as an independent nation—would perceive the mass execution of some 300 men. As Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles noted in his diary: “When the intelligent Representatives of a State can deliberately besiege the Government to take the lives of these ignorant barbarians by wholesale… , it would seem the sentiments of the Representatives were but slightly removed from the barbarians they would execute.”

Nevertheless, Lincoln’s compassion played the largest role in the predicament. In their lengthy debates over Civil War military court verdicts, Judge Advocate Holt often urged execution. Lincoln usually demurred, saying, “I don’t think I can do it,” or “I am trying to evade the butchering business lately.” Holt said Lincoln’s “constant desire was to save life.” John Hay, the other of Lincoln’s personal secretaries, wrote in his diary, “I was amused at the eagerness with which the President caught at any fact which would justify him in saving the life of a condemned soldier.” Statistics confirm these observations. In his review of death sentences for desertion, Lincoln disagreed with the trial courts at a rate of 75 percent initially, increasing to 95 percent by the middle of the war. He rarely approved execution for cowards because “it would frighten the poor devils too terribly,” and he never allowed execution for those who slept on sentry duty. In reviewing the death sentences of civilians handed down by military commissions, Lincoln disagreed with 60 percent of the trial courts. He was only merciless in cases involving cruelty or sex offenses.

Any death sentence for rape or murder, whether from courts martial or commission, stood a 50- to-80 percent chance of being upheld upon presidential review. Lincoln issued his decision in the Dakota cases on December 6, 1862. He later explained his rationale to the Senate: “Anxious to not act with so much clemency as to encourage another outbreak on the one hand, nor with so much severity as to be real cruelty on the other, I caused a careful examination of the records of trials to be made, in view of first ordering the execution of such as had been proved guilty of violating females. Contrary to my expectations, only two of this class were found. I then directed a further examination, and a classification of all who were proven to have participated in massacres, as distinguished from participation in battles.” Lincoln’s order to Sibley—in his own handwriting—allowed the execution of only 39 of the 303 condemned Dakota.

Of these, 29 had been convicted of murder, three for having “shot” someone, two for participating in “massacres,” and one for mutilation. As Lincoln told the Senate, only two had been convicted of rape. Curiously, the president allowed the executions of two men who were convicted merely for participating in battles. Lincoln spared Godfrey, as the military commission requested, and two weeks later spared another man due to newly discovered exculpatory evidence. “The other condemned prisoners,” Lincoln ordered Sibley, “you will hold subject to further orders, taking care that they neither escape, nor are subject to any unlawful violence.” With his “massacres” versus “battles” standard, Lincoln offered clemency to 265 of the condemned Dakota, or 87 percent of them. Some analysts have argued that jurisdictional defects in the proceedings—namely, that the commission lacked authority because martial law had not been declared, and that the Dakota were not tried for military-type violations, but the common-law crimes of rape and murder—nullify Lincoln’s well-intentioned efforts. While these arguments are probably true in theory, the reality of the situation was different.

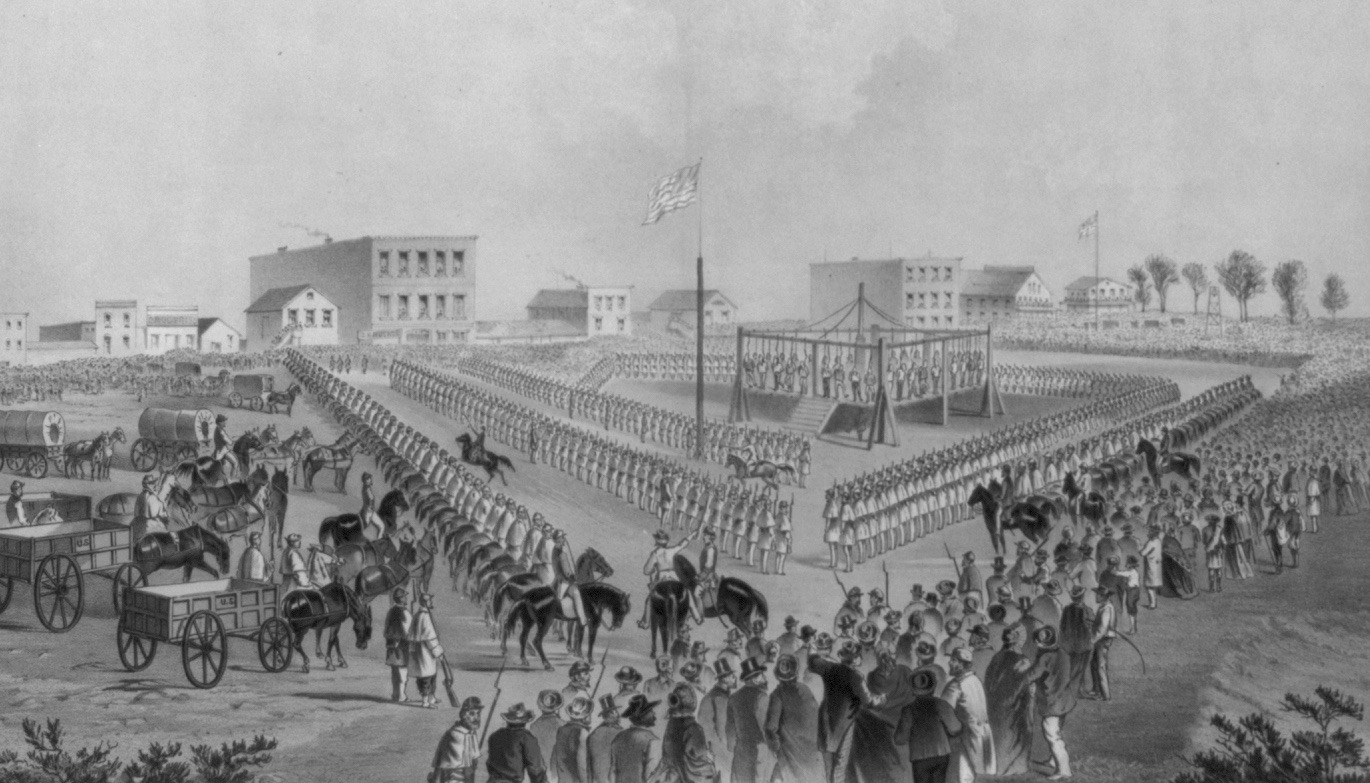

This was wartime; Lincoln could not have reversed the convictions wholesale, either ordering new trials or disapproving the proceedings entirely. The former would have caused great delay and the latter great outrage, either of which could have led to mob violence in Minnesota. Such actions would not necessarily have prevented the Dakota from being tried in state courts, where they would have received little sympathy from citizen juries. Lincoln had to make a final decision on the matter, and he did: his “massacres” versus “battles” standard recognized all legal and political issues and encompassed all reasonable solutions. His standard presented a plausible, practical effort to correct the verdicts and assign more appropriate standards of responsibility. On December 27 President Lincoln received a telegram from Sibley: “I have the honor to inform you that the thirty-eight Indians and half-breeds, ordered by you for execution, were hung yesterday at Mankato, at 10 a.m.

Everything went off quietly, and the other prisoners are well secured.” The politicians and citizens of Minnesota had taken the president’s order with a smoldering reserve, and there were no acts of vigilantism or mob law. The Dakota plunged simultaneously to their deaths on one giant gallows before thousands of spectators. It remains the largest mass execution in American history. In the next year Sibley led a punitive expedition against those Dakota who had escaped after the conflict.

A settler killed Little Crow after the Indian had sneaked back into Minnesota. After spending a freezing, disease-ridden winter at Fort Snelling, the remaining Dakota were banished to an inhospitable reservation in South Dakota. All, that is, except one man named Chaska. In an example personifying the trial defects, Chaska—who had saved the lives of captive white women—was errantly hanged instead of one Chaskaydon, convicted of shooting and mutilating a pregnant woman.

The marshal of the prison had gone to release Chaska: “[B]ut when I asked for him, the answer was ‘You hung him yesterday.’ I could not bring back the redskin.

this article first appeared in American history magazine

Facebook @AmericanHistoryMag | Twitter @AmericanHistMag