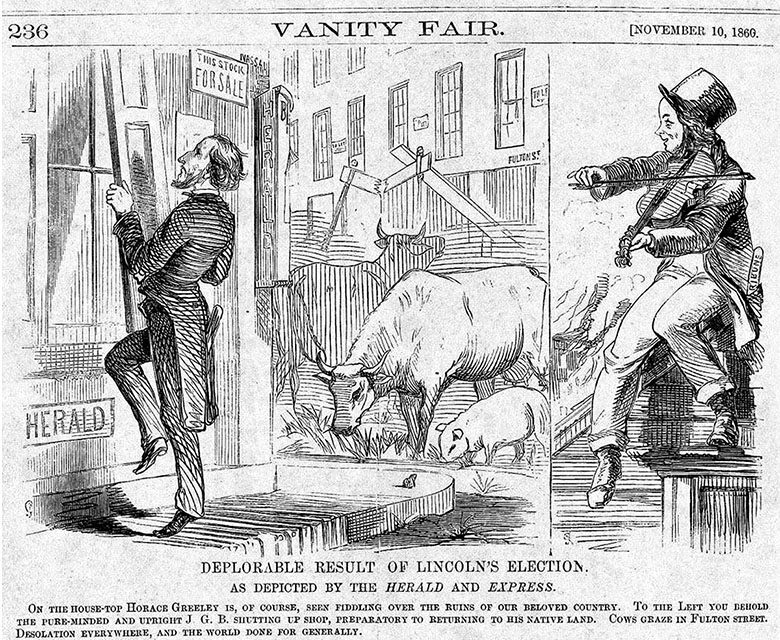

The New York Tribune’s Horace Greeley privately thought Lincoln timid in the run-up to First Bull Run. But if Lincoln’s so-called timidity ever existed, it vanished quite soon after that battle—at least toward a new foe he judged nearly as dangerous as armed Rebels: Antiwar, anti-administration, anti-recruitment newspaper editors. Against these foes, the Union government commenced an additional war, which Greeley eventually came to support almost as ardently as the fight to restore the Union.

Months earlier, Lincoln had assured delegates to a Washington peace conference that even in the wake of secession, he still believed a free press “necessary to a free government.” Outright rebellion altered his thinking on the subject, especially after the July battle that was supposed to end the war in an afternoon. For his part, Greeley may have believed that, following the Bull Run defeat, Lincoln “still clung to the delusion that forbearance, and patience, and moderation, and soft words would yet obviate all necessity for deadly strife.”

But the record suggests otherwise. Following Bull Run, the administration turned its attention not only to forging weaponry and raising more troops, but also to quelling home-front newspaper criticism that the president, his Cabinet and many Northern newspaper editors believed was morphing from tolerable dissent into nation-threatening treason.

In the wake of this tightened oversight, some Democratic war opponents tried arguing that constitutional guarantees of free speech and free press must remain absolute no matter what the danger of an armed revolt. Even Lincoln’s friend Edward Baker, in one of his final speeches in the U.S. Senate before accepting his fateful military commission, insisted that neither the eradication of slavery nor the preservation of the Union justified threats to “the liberty of the press.” Critics pointed out that the First Amendment unequivocally guaranteed: “Congress shall make no law…abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press.” And Congress never did. This did not inhibit the administration from determining that in an unprecedented case of rebellion, and under the powers the president had claimed in order to crush it, military necessity superseded constitutional protection, and contingency trumped the organic assurances of freedom of expression within the Bill of Rights.

Based on this argument, the administration began conducting—or, when it occurred spontaneously, tolerating—repressive actions against opposition newspapers. At their most unobjectionable level, the safeguards were initially meant to keep secret military information off the telegraph wires and out of the press. But in other early cases censors also prevented the publication of prosecession sentiments that might encourage border states out of the Union. In an anonymous dispatch for the New York Examiner, presidential clerk William Stoddard probably spoke for the White House in complaining that, cut off from their usual sources, “the legion of daily newspaper reporters” roamed “the streets and camps…pouncing, with hawk-like avidity, upon every poor little stray item which, in their palmier days, they would have scorned to notice.” And some of those “items,” the administration believed, should remain secret.

Eventually, the military and the government began punishing editorial opposition to the war itself. Authorities banned pro-peace newspapers from the U.S. mails, shut down newspaper offices and confiscated printing materials. They intimidated, and sometimes imprisoned, reporters, editors and publishers who sympathized with the South or objected to an armed struggle to restore the Union. For the first year of the war, Lincoln left no trail of documents attesting to any personal conviction that dissenting newspapers ought to be muzzled. But neither did he say anything to control or contradict such efforts when they were undertaken, however haphazardly, by his Cabinet officers or military commanders. Lincoln did not initiate press suppression and remained ambivalent about its execution, but seldom intervened to prevent it.

Did press dissent really pose an existential threat to national security? Probably not, certainly not in the free, loyal Northern states. But a frightened Northern public and most pro-Republican editors not only failed to object to the more paranoid view, they encouraged it, even when it triggered outright violence against newspapers. Perhaps, for these supportive editors, the additional appeal of reducing the Democratic competition seemed irresistible.

The Union military laid the foundation for press censorship well before Bull Run. Unable to read, much less censor, every newspaper published in the country, it acted promptly to control both the source and distribution points for news. Soon after the April attack on Fort Sumter, it cut the telegraph wires between Washington and Richmond. Then the administration banned the use of the postal service and other exchange routes in and out of the rebellious states. National papers with large circulations in the South—particularly the New York Herald—suffered considerably as their Southern readership dwindled. Soon all of Washington’s telegraph wires, the standard medium for transmitting news from city to city, fell under military control—as The New York Times founder Henry Raymond had learned to his consternation after Bull Run. In the aftermath of the stinging Federal defeat there, a season of official crackdowns on individual newspapers commenced. The hostility toward pro-peace, pro-slavery journals made the angry crowd that menaced the Herald offices after Sumter seem like a band of carolers by comparison.

Suppression fever flared up first in an area of northern Virginia that fell quickly under Union control. It was a “desecrated” flag that stimulated the eruption. On May 24, a young Lincoln protégé, the dashing Zouave Colonel Elmer Ephraim Ellsworth, marched his colorfully attired men into Alexandria determined to tear down an offending Confederate flag from atop one of the town’s seedier hotels. Ellsworth captured the banner, but paid with his life when the innkeeper blew open his chest with a shotgun as the colonel descended the hotel staircase. As the first Union officer killed in the Civil War, Ellsworth became an instant martyr—his “memory…revered, his name respected,” mourned The New York Times.

With the rallying cry “Avenge Ellsworth” on their lips, Federal troops soon occupied the entire Washington suburb. Union Colonel Orlando Willcox then ordered the Alexandria Gazette to publish a proclamation declaring martial law. Rather than comply, editor Edgar Snowden shut down the paper, whereupon Union soldiers seized the office, smashed property and allegedly stole valuables. A pre cedent had been established. Snowden lay low until October, when he launched a new journal called the Alexandria Local News, vowing the venture would focus on “the truth, as far as that can be reached.” Union forces kept their eye on Snowden, and his comeback proved fleeting. When later that year Union troops seized the rector of an Alexandria church merely for omitting the customary prayer for the president, Snowden denounced the arrest as an “outrage.” Soldiers responded by setting fire to the headquarters of the Local News. The beleaguered editor suspended operations yet again, only to reopen the old Gazette in 1862. Two years later he himself would be arrested.

Situations like these became commonplace in most of the volatile border states, where Union commanders struggled to prevent pro-slavery interests from mounting secession efforts. In Maryland, for example, Lincoln authorized each military commander “to arrest, and detain, without resort to the ordinary processes and forms of law, such individuals as he might deem dangerous to the public safety.” The broad order by no means exempted journalists. When that summer the pro-secession Baltimore Exchange editorialized that “the war of the South is a war of the people, supported by the people,” while the “war of the North” was “the war of a party…carried out by political schemers,” military authorities shut down the paper, arrested editors W.W. Glenn and Francis Key Howard—the latter, a grandson of the author of the National Anthem—and shipped them off to prison without trial. Howard’s surviving personal papers suggest that authorities may have acted prudently in his case: The records included secret resolutions in which Baltimore leaders pledged violent support for the Confederacy. He remained in detention, his case unresolved, for months, and for a time he was confined at Fort McHenry in Baltimore Harbor, the very installation whose bombardment half a century earlier had inspired his grandfather to write “The Star-Spangled Banner.” Howard also spent time at that most notorious of press dungeons, New York’s Fort Lafayette, and later wrote an unrepentant memoir about his lengthy confinement titled Fourteen Months in American Bastilles.

In short order, acting under instructions from Secretary of War Simon Cameron, federal marshals suppressed four more of Baltimore’s anti-Union journals and imprisoned a number of their proprietors. “The secession organs in Richmond were not more unscrupulous or desperate in their attempts to undermine and overthrow the Government at Washington than these same in Baltimore,” The New York Times cheered. Henry Raymond’s only complaint was that it cost the federal government millions of dollars “to repair the mischief of the un-muzzled organs of treason in Baltimore.” That there was some truth to the suspicions of treason among local newspapermen was confirmed when onetime reporter J.B. Jones, making his way through the city en route to Richmond, reassuringly found Baltimore Sun editor Arunah Abell to be “an ardent secessionist.” In September, emboldened federal authorities arrested yet another Maryland editor, Daniel Deckart, for publishing a “disloyal sheet” in Hagerstown. Deckart ended up confined for more than a month at Washington’s dank Thirteenth Street prison.

Inevitably suppression fever, like the war itself, spread west, particularly to Missouri and Kentucky, two border states where Union loyalty may have been a minority sentiment. During the post–Bull Run summer, as strategically crucial Missouri teetered on the brink of secession—in the end it never left the Union but remained a fierce battleground—commanding General John C. Frémont moved under martial law to consolidate control over the press. Early on, the army suppressed the pro-Confederate St. Louis State Journal and arrested editor Joseph W. Tucker. Back in New York, the Times again showed no sympathy for such brethren. Raymond pointed out that “the chief Western organ of the Southern conspirators” had “given itself up to stimulating the mob of St. Louis to sedition and bloodshed, and inaugurating the reign of anarchy in the city and state.” Federal troops also sacked the Cape Girardeau Eagle, closed down the Hannibal Evening News and padlocked newspapers in Missouri outposts like Warrensburg, Platte City, Osceola, Oregon and Washington.

A politician destined to be embroiled in later free speech controversies—Democratic congressman Clement L. Vallandigham of Dayton, Ohio—responded to these shutdowns with a vow to introduce federal legislation “to secure the freedom of speech and of the press.” The initiative received little support. Raymond continued to mock the theory that “organs of treason” could be protected to publish at will. “The United States is now at war with Secessionism,” he editorialized. “…Whatever ministers to it must be destroyed; whatever stands in the pathway of our triumph must be overthrown.” The Times adamantly rejected the “vague notion afloat that freedom of speech carries with it some special and peculiar sanctity.”

Less than a week after that comment appeared in print, one of the newly minted generals under Frémont’s command acted to suppress a newspaper in yet another Missouri district. His name was Ulysses S. Grant. On August 26, Grant moved not only against grocers supplying food to secessionists, he also ordered the shutdown of the Booneville Patriot, published some 40 miles from his Jefferson City headquarters. “Bring all the printing material, type &c with you,” he directed his troops. “Arrest J.L. Stevens and bring him with you, and some copies of the paper he edits.” Stevens was no more entitled to civil rights, Grant maintained, than the other “obnoxious” Confederate sympathizers. “Give secessionists to understand what to expect if it becomes necessary to visit them again.” Just a week later, Grant reported that “some of the despatches [sic]” earmarked for telegraphing “by one of the newspaper correspondents” accompanying his army were “so detrimental to the good of the service that I felt it my duty to suppress them,” too. For a time, the assault on the pro-slavery, pro-Confederate press in Missouri continued unchecked—and at both Washington and New York editorial desks, unchallenged. That same month, the military closed down two more St. Louis papers, the War Bulletin and the Missourian, charging that both were “shamelessly devoted to the publication of transparently false statements regarding military movements in Missouri.” When the St. Louis Christian Advocate came to the papers’ defense, the provost marshal warned its editors to adhere to its identity as “a religious paper” or face “the discipline of the department,” too. Military censorship tightened further when the army “seized and destroyed” the St. Louis Daily Evening News, and briefly detained editor Charles G. Ramsay for criticizing Frémont’s failure to rescue a Federal garrison at Lexington, Mo. “We are under a reign of terror,” an anonymous correspondent protested to Postmaster General Montgomery Blair after Ramsay’s arrest. “…Will our President countenance such tyranny?” Blair dutifully forwarded the warning to Lincoln, but the president offered neither comment nor relief.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

By September, suppression fever had reached the Bluegrass State. On the 9th, an angry Union loyalist from Indiana, Charles Fishback, inflamed matters by sending Secretary of State William Seward a batch of recent editorials from the Louisville Courier, a paper that Horace Greeley had earlier branded “a Secession Press.” Was it not “about time,” Fishback implored Seward, that “the editor were an occupant of Fort Lafayette or some other suitable place for traitors? The people are getting tired of sending their sons to fight rebels while such as this editor, more mischievous by far than if armed with muskets, are allowed to furnish aid and comfort to the enemy unmolested.” On the 18th, three days after a Cabinet meeting at which the matter may well have come up for discussion, the Post Office obliged by banning the Courier from the U.S. mails. The following day, federal authorities raided the newspaper’s offices and took several employees into custody, including assistant editor Reuben T. Durrett, whom they charged with publishing “editorials of the most treasonable character.”

It was not a banner day for free speech in Kentucky. Also seized as a traitor on September 19 was the state’s former governor, Charles S. Morehead, along with one Martin W. Barr, who, it was alleged, “used his position as telegraph agent for the Associated Press to advance the insurrectionary cause.” The case of the ex-governor of course dominated the news, relegating the Durrett arrest to the background. In fact, because Durrett was linked to the detention of so important a politician, it became one of the first press arrest cases in which Lincoln involved himself directly, though not, as it turned out, sympathetically.

The Courier’s racist but pro-Union owner George D. Prentice acted to absolve himself from his employee’s views, but also tried to exert influence to liberate him. Prentice had previously called on Kentucky to remain neutral, and expected the president to bestow patronage influence on him in return. Now he wrote Lincoln to urge leniency for Durrett. Perhaps he was “a secessionist,” Prentice conceded, “but he has never done any harm in our community….I would rather give a portion of the brief remnant of my life than have his confinement protracted.” Lincoln remained unmoved. He coolly scribbled on the back of Prentice’s plea: “sent to Fort Lafayette by the military authorities of Kentucky and it would be improper for me to intervene without further knowledge of the facts than I now possess.”

The “further knowledge” soon arrived—of a decidedly condemnatory nature—courtesy of pro-Union Kentucky Democrat Joseph Holt, secretary of war under James Buchanan, but now working tirelessly to keep his home state from seceding. Holt informed Lincoln that Durrett had indeed “done everything to incite the people of Kentucky to take up arms against the General Government,” adding, “His arrest has rejoiced the hearts of the Union men, and his discharge…would in my judgment be a fatal mistake.” Holt enclosed a cache of Durrett “paragraphs,” in one of which the journalist asserted that Kentucky was “under no obligation to remain in the Union, but under many to leave it.” Durrett remained in confinement, and Lincoln rewarded Holt’s loyalty by naming him judge advocate general of the Union armies.

Undaunted, Durrett’s sympathizers pressed on for his release through other channels. To no avail, they wrote to Secretary of the Treasury Salmon P. Chase on October 10, arguing that Durrett was a “harmless man” who “hardly knew which side he was on,” and again petitioned Lincoln for mercy by pointing out that his confinement had left the journalist’s family “financially ruined.” Only in October did Lincoln finally tell Seward: “I am willing if you are that any of the parties may be released”— that is, if the president’s reliable Kentucky allies James Guthrie and James Speed agreed that “they should be.” Yet not until Durrett himself wrote Seward in December to protest his innocence and complain bitterly about conditions in prison was his case finally reopened. Seward finally relented, ordering the journalist’s release providing he agree to do nothing “hostile to the United States.”

Durrett swore to a standard oath of allegiance on December 9 and at last became a free man—after 10 weeks inside a series of federal prisons without trial—and only after Prentice again reminded Lincoln of “the importance of the Journal as an agency in this struggle.” For good measure, Prentice added that he could sustain the paper only if Lincoln awarded him contracts to supply the army with weapons, animals and food. Few 1861 suppression episodes better illustrated the dangers facing border state editors who opposed the Union, or the rewards expected by those who supported it. At least Lincoln could console himself in the belief that “I understand the Kentucky arrests were not made by special direction from here.” This was small consolation to Durrett, who was still languishing in prison when his employer began securing lucrative government contracts.

Similarly chilling incidents took place in Northern states that had voted strongly for Lincoln in 1860, and posed no danger of abandoning the Union. Though unsanctioned by the government, these attacks, most of them spontaneous, were seldom restrained by local authorities, and rarely punished in court. Nearly all the aggression reflected shame and fury over the humiliation at Bull Run. In much the same way official Washington attempted to place undeserved blame for that fiasco on the London Times, residents of Northern towns and villages long accustomed to tolerating both Republican and Democratic newspapers now unleashed their pent-up rage on Democratic papers that questioned military recruitment or mocked the soldiers’ performance on the battlefield.