“No one not here can conceive the panic in the state,” exclaimed Minnesota Governor Alexander Ramsey in a telegram to President Abraham Lincoln. At the time Ramsey wired the White House, on August 26, 1862, thousands of his constituents were fleeing from their homes across 23 counties. Terror, fed by grim evidence and wild rumors, had engulfed Minnesota in the form of an American Indian uprising.

The fearful events had been ignited in a flash after years of smoldering portents. Organized as a territory in 1849, Minnesota had been inundated throughout the next decade with settlers in search of cheap, fertile farmland. The influx of white homesteaders onto ancestral Indian lands fueled resistance, particularly from the Dakota Sioux.

In 1851, in two separate treaties, the Dakota ceded land to the federal government in return for annual payments in foodstuffs and gold, and a reservation. Nine years later, as Minnesota obtained statehood, a third treaty eliminated Dakota claims to land north of the Minnesota River, further reducing the size of their reservation.

Victimized by late payments of annuities and the practices of unscrupulous traders, the Dakotas festered with anger. Two years of crop failures and a bitter winter had resulted in widespread hunger by the summer of 1862. When a reservation agent refused to release food to the Indians until the annual payment arrived, tribal leaders protested. At the meeting a trader, Andrew Myrick, reportedly said, “So far as I am concerned, if they are hungry, let them eat grass.”

On August 17, four Dakota warriors killed five settlers, including two women, near Litchfield while foraging for food. A tribal council decided that night to drive the whites from the river valley. Led by Chief Little Crow, the Dakotas attacked the Redwood Agency, killing more than 40 civilians and soldiers. Among the dead was Myrick, whose body had grass stuffed into the mouth.

During the next two weeks, bands of Sioux swept through the countryside, burning farmsteads, slaying men and seizing scores of women and children. An estimated 650 Dakotas attacked the village of New Ulm, where the defenders fought from behind street barricades. Although most of the town’s buildings were destroyed, the warriors were repulsed. By month’s end, much of the white population of southern Minnesota had abandoned the region.

When the Dakotas struck, Governor Ramsey appointed Colonel Henry Hastings Sibley (not to be confused with his distant cousin, Confederate General Henry Hopkins Sibley) to raise a volunteer force and lead it against them. Sibley’s ill-armed and ill-equipped 1,400- man army advanced up the Minnesota River valley, finally meeting Little Crow’s warriors at Wood Lake on September 23. The engagement amounted to a standoff, but it ended the uprising. While Little Crow and other Dakotas fled west, the soldiers herded about 2,000 Dakotas into custody. Sibley, who was promoted to brigadier general on September 29, established a military commission to “try summarily” individual Sioux for “murder and other outrages.” A diarist recorded that there was a “thirst for revenge” in the white community.

A week before the Battle of Wood Lake, Maj. Gen. John Pope arrived in Minnesota. Exiled by the Lincoln administration to the Department of the Northwest after his defeat at Second Bull Run, Pope directed the final efforts against the Dakotas. In the ensuing weeks, Pope initiated plans for future campaigns against the tribe in Dakota Territory. The military commission, meanwhile, conducted the semblance of trials against 393 accused warriors, convicting 321 of them and sentencing 307 to death.

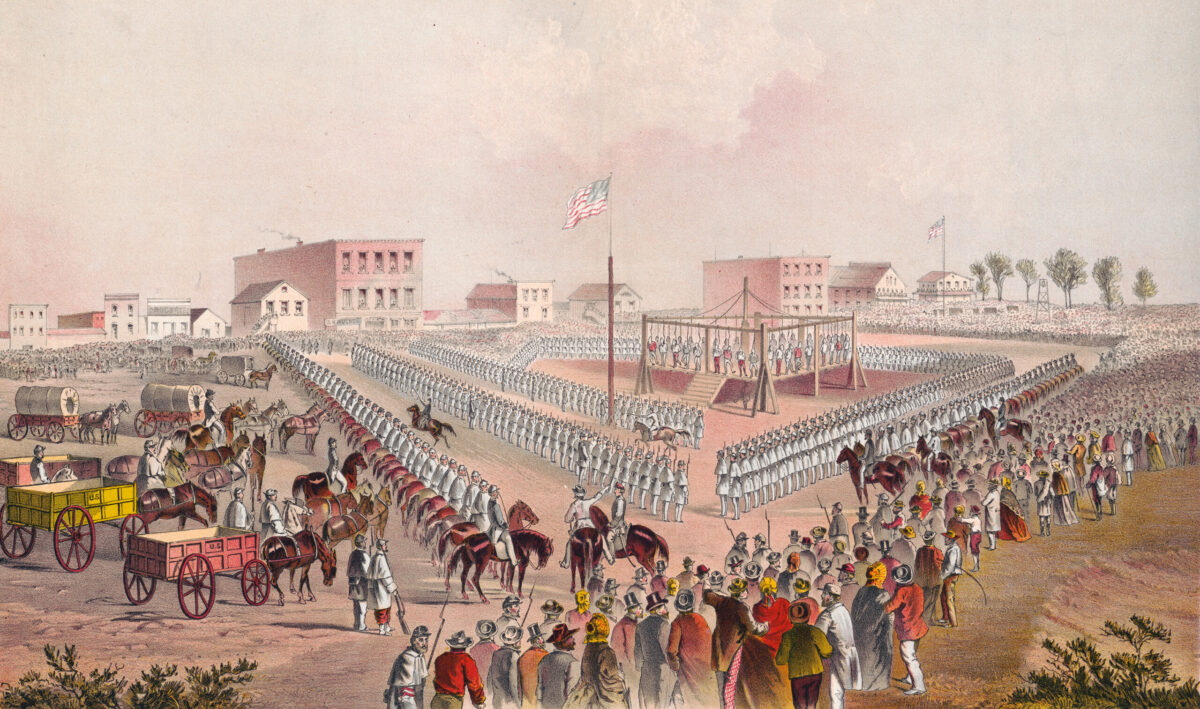

Lincoln directed, however, that the records of the proceedings be forwarded to him before any sentences were carried out. He listened to pleas of clemency and knew of the clamor for revenge. In the end, Lincoln approved the executions of 38 Dakotas who had been convicted of either rape or murder. New evidence later spared one of the condemned men. On December 26, in Mankato, Minn., 2,000 onlookers watched the hanging of the 38 Dakota men, the largest mass execution in American history.

Although casualty figures conflict, it appears that 71 Indians (including those executed), 77 soldiers and over 800 civilians lost their lives as a result of the Dakota uprising in the summer of 1862. For the Sioux, however, the defeat held greater consequences. The federal government nullified the treaties, ordered their banishment from Minnesota and increased the bounty on their scalps. The military conducted campaigns against the tribe in Dakota Territory during the next three years.

A white survivor of the uprising, writing in a journal years later, stated: “For had the Indians been treated as agreed, honest and upright, this bloody day in Minnesota’s history would have been avoided. But as it was, the Indians never had a square deal.” In the midst of a national civil war, in a place far removed from its terrible battlefields, a turning point had been reached in the relations between a powerful Indian tribe and a more powerful foe. More bloody days lay ahead.

Originally published in the June 2006 issue of Civil War Times.