George B. McClellan, Robert E. Lee, and a watershed campaign.

Readers might assume from the title that this article will explore the Battle of Antietam. After all, Antietam, together with Gettysburg and Vicksburg, often appears on lists of the war’s crucial turning points. The arguments for all three are well known. Antietam brought emancipation to center stage via Abraham Lincoln’s preliminary proclamation five days after the battle, Gettysburg marked the “High Water Mark” of the rebellion and sent Confederate fortunes tumbling toward Appomattox, and Vicksburg dealt a fatal blow to the Rebels by closing the Mississippi River. But this article addresses a turning point more important, though far less often acknowledged, than any of those three—the Seven Days Campaign of June-July 1862. In the broader sweep of the conflict, George B. McClellan’s failure and Robert E. Lee’s successful effort marked a decisive moment in the Eastern Theater that in turn profoundly shaped the larger direction of the conflict.

A brief narrative of the campaign will set up an assessment of its consequences. Between March and the end of May 1862, McClellan led the Army of the Potomac, approximately 100,000 strong, up the Virginia Peninsula to the outskirts of Richmond. On June 1, Robert E. Lee replaced Joseph E. Johnston, who had been wounded the previous day at Seven Pines, in command of the Confederate army defending Richmond. The next four weeks provided a striking contrast between the two commanders. No general exhibited more aggressiveness than Lee, who believed the Confederacy could counter the Union’s superior numbers only by seizing the initiative. When “Stonewall” Jackson’s troops arrived from the Shenandoah Valley and other reinforcements arrived, Lee’s army, at more than 90,000 strong, would be the largest ever fielded by the Confederacy. By the last week of June, the Army of the Potomac lay astride the Chickahominy River, two-thirds of its strength south of the river and one-third north of it. Lee hoped to crush the portion north of the river and then turn against the rest.

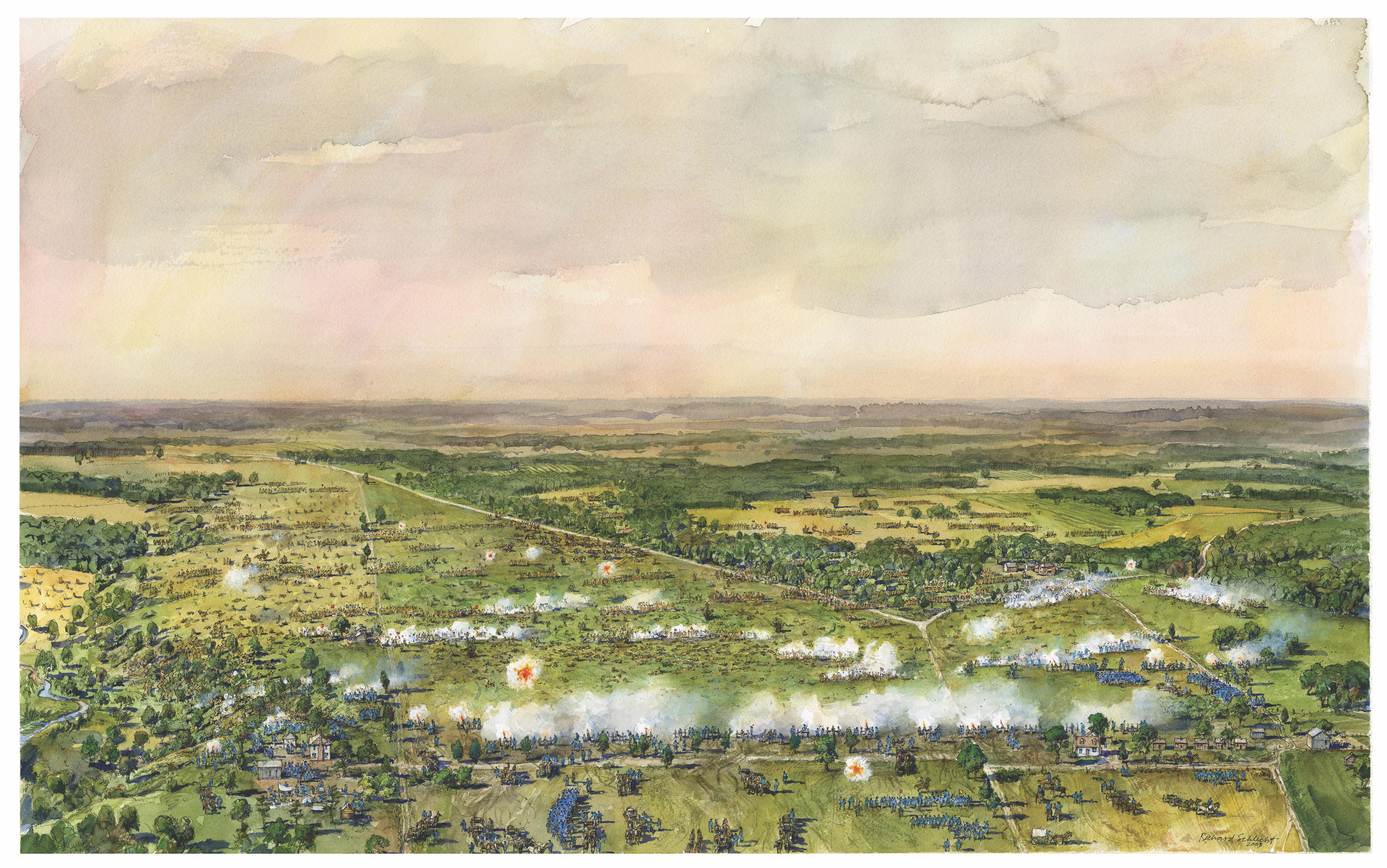

Heavy fighting began on June 26 at the battle of Mechanicsville and continued for the next five days. At Mechanicsville, Lee expected Jackson to hit Union Maj. Gen. Fitz John Porter’s right flank. The hero of the Valley failed to appear in time, however, and A.P. Hill’s Confederate division launched a futile assault about mid-afternoon. Porter retreated to Gaines’ Mill, where Lee struck again on the 27th. Once again Jackson stumbled, as more than 50,000 Confederates attacked along a wide front. Late in the day, Porter’s lines gave way, and he withdrew across the Chickahominy to join the rest of McClellan’s army. By this point, both Lee and McClellan had made their most important decisions: Lee to press the offensive relentlessly; McClellan to abandon all momentum and think only of retreat.

In the wake of Gaines’ Mill, McClellan changed his base from the Pamunkey River to the James River, where U.S. naval power could support the Army of the Potomac. Lee followed the retreating Federals, seeking to inflict a killing blow as they withdrew southward across the Peninsula. The Confederates mounted ineffectual attacks on the 29th at Savage’s Station and far heavier ones at Glendale (also known as Frayser’s Farm) on the 30th. Time and again they failed to act in concert. By July 1, McClellan stood at Malvern Hill, a splendid defensive position overlooking the James. Lee resorted to unimaginative frontal assaults that afternoon, leaving more than 5,000 Confederate casualties littering the slopes of Malvern Hill. Although some of McClellan’s officers urged a counterattack against the obviously battered enemy, “Little Mac” retreated down the James to Harrison’s Landing, where he hunkered down, awaited Lee’s next move, and issued endless requests for more men and supplies.

Confederate losses at the Seven Days exceeded 20,000 killed, wounded, and missing, while the Union’s surpassed 16,000—only Gettysburg produced more casualties in a single battle. The campaign’s importance, however, extended far beyond setting a new standard of carnage in the war. Lee had seized the initiative, dramatically altering the strategic picture by dictating the action to a compliant McClellan.

Four questions provide a helpful framework to gauge the importance of the Seven Days. The first involves military context: How did the campaign shaped by choices McClellan and Lee made in June and July figure in the entire tapestry of war during 1862? The first months of the year proved decidedly favorable to United States forces. Along the Mississippi River, they made excellent progress toward the strategic goal of taking control of the great waterway and dividing the Confederacy into eastern and western parts. Well before the first shots at Mechanicsville on June 26, Federal land and naval operations had seized Confederate strongpoints on the upper and lower Mississippi from Columbus, Kentucky, to New Orleans. The stretch of river between Baton Rouge and Vicksburg remained in Rebel hands, but as a conduit for transporting goods and as an outlet to the Gulf of Mexico for exports, the Mississippi had ceased to be a Confederate river.

Federal gains in the Western Theater rivaled those along the Mississippi. Ulysses S. Grant’s forces captured Fort Henry on February 6 and Fort Donelson 10 days later, opening the Tennessee and Cumberland rivers respectively, and stopped a Confederate counteroffensive at Shiloh on April 6-7. Don Carlos Buell’s army occupied Nashville, with its crucial manufacturing, transportation, and distribution facilities, on February 25; just more than three months later, Henry W. Halleck led 100,000 Federals into the railroad center of Corinth, Miss. In less than four months, the United States had seized control of a vast swath of the Confederate heartland between Kentucky and Mississippi, a region rich in iron, industry, agricultural products, livestock, and other vital resources.

No part of the strategic puzzle loomed larger than Virginia, and Confederates could find little there to counter depressing news from west of the Appalachians. Joe Johnston’s army abandoned its lines near Manassas Junction early in March and retreated from a second position along the Rappahannock River a month later. The action shifted to the Peninsula, where McClellan’s Army of the Potomac landed at Fort Monroe and moved slowly toward Richmond. Confederates gave up Yorktown on the 3rd of May, Williamsburg on the 5th, and Norfolk on the 9th. By the last week of the month, McClellan had reached the environs of Richmond, more than 30,000 troops under Irvin McDowell stood at Fredericksburg, and thousands more lay in the Shenandoah Valley and western Virginia. The Battle of Seven Pines (Fair Oaks) closed the month with yet another Confederate failure, as Johnston’s ill-executed assaults produced several thousand casualties but left intact the strategic status quo. Stonewall Jackson’s small victories in the Shenandoah Valley between May 8 and June 9 cheered Confederates hungry for good news from the battlefield but in no way offset the larger reality that McClellan’s army was closing in on Richmond. Had Richmond fallen in June or July, the Valley Campaign would be no more than an insignificant footnote in Civil War history.

One last point about the military situation in the first half of 1862 bears mention. Operations in the Eastern Theater probably carried more weight than those elsewhere. This is not to say everyone looked to the East as the theater of decision—that surely was not the case. But a majority of civilians in the United States and the Confederacy, members of the U.S. Congress, and foreign observers almost certainly formed their primary impressions about how the war was going by reading accounts of Eastern operations. Several factors explain this phenomenon. The centers of population clustered in the East, as did newspapers with the highest circulations. The largest and most prominent armies commanded by the most celebrated generals fought in the East, and they campaigned in the shadow of the respective national capitals. Some observers at the time, including Abraham Lincoln, lamented what they considered an undue focus on the East, as have a number of modern historians. Yet the fact remains that what happened during the Seven Days would exert all the more influence because of where it occurred.

The second framing question concerns civilian expectations as the armies prepared for their collision at Richmond. People in the United States envisioned success from the Army of the Potomac. This expectation derived from the triumphs on Western battlefields that had prompted newspapers to indulge in lavishly optimistic projections about McClellan’s prospects for a decisive victory. Many editors across the loyal states claimed that Confederate morale had plummeted, as when a New York Times headline in late April described “A PANIC THROUGHOUT THE SOUTH.” A few weeks earlier, Benjamin Brown French, the commissioner of public buildings in Washington, recorded that “news of victory after victory over the rebels has come and over them we have all rejoiced, and appearances indicate that the game of secession is nearly played out.” Senator Charles Sumner of Massachusetts, a Radical Republican who did not wish the war to end without emancipation, similarly predicted an early termination of fighting. “It seems pretty certain that the military power of the rebellion will be soon broken,” he wrote to the Duchess of Argyll on June 9. “What then? That is the great question. [Secretary of State William H.] Seward assured me yesterday that it would ‘all be over in 90 days.’ ”

Sentiment in the Confederacy contrasted sharply with that in the United States. Every Union military success promoted war-weariness among the Rebels. Shortages of food, territory lost to U.S. invaders, and stringent governmental actions, most notably the Conscription Act of April 16, 1862, added to a gloomy situation. In mid-May, a bureaucrat in Richmond aptly described deteriorating morale: “Our army has fallen back to within four miles of Richmond… Is there no turning point in this long lane of downward progress? Truly it may be said, our affairs at this moment are in a critical condition.”

The absence of an army commander around whom the Confederate people could rally deepened the crisis. Four officers had stood out during the first stage of the war: P. G. T. Beauregard, the “Hero of Sumter” and co-victor at First Manassas; Joseph E. Johnston, co-commander at First Manassas and then head of the primary army in Virginia; Albert Sidney Johnston, who directed affairs in the sprawling Western Theater; and Robert E. Lee, who brought to his Confederate service a reputation as Winfield Scott’s favorite soldier. By the time of the Seven Days, A. S. Johnston lay dead of wounds at Shiloh, and Beauregard had fallen out of favor with Jefferson Davis and gone into temporary exile after the loss of Corinth. In Virginia, Joe Johnston had retreated so often that many had come to question his abilities before Seven Pines. Lee stepped into Johnston’s position with his public image tarnished because many Confederates thought he had performed timidly in western Virginia during the autumn of 1861 and while in Charleston during the winter of 1861-62. Upon Lee’s assignment to replace Johnston, one Confederate staff officer recalled, “some of the newspapers…pitched into him with extraordinary virulence, evidently trying to break him down with the troops & to force the president to remove him.”

This brief review of events and opinion indicates how much was at stake as the armies prepared for a climactic contest outside Richmond—and raises the third question; namely, how did the Seven Days influence morale in the armies and on the home fronts? The Army of the Potomac is a good place to begin. McClellan’s reputation suffered among those who believed he had retreated unnecessarily, given up favorable ground after repelling Lee’s attacks at Malvern Hill, and fumbled a brilliant opportunity to capture the enemy’s capital. Months of hard work had come to nothing because the powerful Union host withdrew to Harrison’s Landing. Mixing sarcasm with disgust, a junior officer in the engineers noted how some of McClellan’s admirers “deify a General whose greatest feat has been a masterly retreat.”

Yet Little Mac remained immensely popular among the majority of his men. Speaking for this element of the army, a private in the 15th Massachusetts credited Rebel generals with movements that compelled McClellan to retreat from the Chickahominy to the James, adding, in the type of language mocked by the junior engineer, that the withdrawal “was one of the most brilliant achievements of the War.” Frederick Law Olmsted, general director of the U.S. Sanitary Commission, conversed with officers and enlisted men at Harrison’s Landing immediately after the Seven Days. He concluded that the soldiers “believe that by the sacrifice of their lives they have secured an opportunity to their country” and with reinforcements would be eager to go after the Rebels again.

The Seven Days exacerbated the already poisonous distrust between Democratic generals in the Army of the Potomac and Republicans in Washington. Radical Republican Senator Zachariah Chandler of Michigan, a member of the Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War, attacked McClellan unsparingly in the committee and on the floor of the Senate. Privately, Chandler called McClellan “an imbecile if not a traitor” who had “virtually lost the Army of the Potomac.”

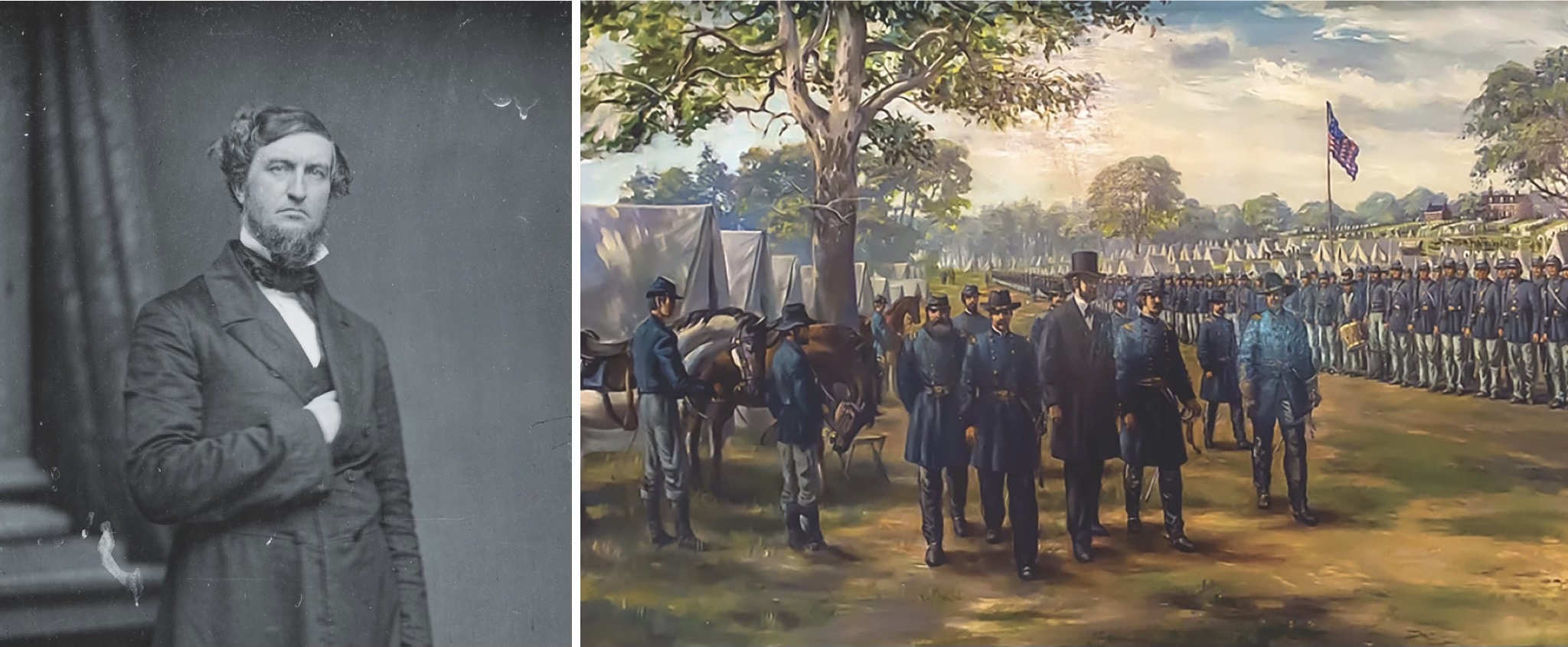

Abraham Lincoln journeyed to army headquarters at Harrison’s Landing on July 8-9, where he learned that McClellan had prepared what later became known as the “Harrison’s Landing Letter.” Little Mac called for a restrained form of warfare against the Confederacy. “Neither confiscation of property…,” he insisted, “or forcible abolition of slavery should be contemplated for a moment.” Lincoln did not need a lesson in politics from McClellan, and the general’s failure to capture Richmond in fact pushed the president toward the kind of conflict his general sought to avoid. The Seven Days had halted the surging momentum of Union military operations and seemed to foreclose the possibility of suppressing the rebellion through a restrained type of warfare.

Deeply affected by the outcome of the Seven Days, Lincoln moved closer to abolitionists and Radical Republicans who demanded seizure of slaves and other Rebel property. On July 22, he informed his Cabinet that he intended to issue a proclamation of emancipation. The Seven Days, therefore, not Antietam, is the key battle in terms of Lincoln’s decision to take this extraordinary step. Congress, meanwhile, had put the finishing touches on the Second Confiscation Act, passed on July 17 and designed to free all enslaved people held by Rebels. Senator Sumner explicitly tied this act’s passage—five days before Lincoln spoke to his Cabinet about emancipation—to Union military failure in the Seven Days. “[T]he Bill of Confiscation & Liberation, which was at last passed, under pressure from our reverses at Richmond,” wrote Sumner in early August 1862, “is a practical act of Emancipation.” Had McClellan been the victor in July 1862, he certainly could have pressed his case for a softer policy. The war could have ended in the summer of 1862 with slavery largely intact—the institution scarcely had been touched in any significant way at that point in the war, and most of the White loyal citizenry surely would not have demanded emancipation in addition to restoration of the Union as a condition for victory.

McClellan’s retreat hit civilians in the United States especially hard because hopes had been so high. They understood that the campaign had failed, though few of them believed it presaged Confederate independence. Overall, they confronted the unpleasant fact that escalating sacrifice and loss likely lay ahead. New Yorker George Templeton Strong, a staunch Republican, noted in his diary on July 11: “We have been and are in a depressed, dismal, asthenic state of anxiety and irritability. The cause of the country does not seem to be thriving much.” Democrats tended to blame the Lincoln administration and Congress rather than McClellan, stressing that the army should have been reinforced before the final battles around Richmond.

In the realm of foreign affairs, the Seven Days carried far more clout with French and British observers than any of the Union successes west of the Appalachians. On August 4, Lincoln answered a French diplomat who suggested the Confederacy might be winning the war. “You are quite right,” the president conceded about the Seven Days, “as to the importance to us, for its bearing upon Europe, that we should achieve military successes; and the same is true for us at home as well as abroad.” But Lincoln bridled at the importance given events in Virginia compared to those farther west: “[I]t seems unreasonable that a series of successes, extending through half-a-year, and clearing more than a hundred thousand square miles of country, should help us so little, while a single half-defeat should hurt us so much.”

The Union’s “half-defeat” at Richmond profoundly affected the Confederacy’s war for nationhood. The Seven Days thrust Lee into the limelight, and his leadership in June and July 1862 began an 11-month process by which he created a finely tuned military instrument that won notable victories. The Army of Northern Virginia rapidly became the most important national institution in the Confederacy and helped sustain morale in the face of mounting odds and hardships on the home front. Fellow citizens began to compare Lee to George Washington, which made sense because he and his army came to function much as Washington and the Continental Army had during the American Revolution. Beginning with the Seven Days, Lee shouldered an increasing share of the burden of sustaining morale among the Rebel citizenry. Long before Appomattox, most Confederates considered him and his army the fullest expression of their national project—and thus his surrender marked the effective end of the conflict.

The Seven Days also began the phenomenon of Confederates focusing progressively more on the Eastern Theater to determine prospects for independence. Lee had given them their first major victory in nearly a year, helping to erase some of the sting from losses in the Mississippi Valley and Middle Tennessee. Over the next ten months, Second Bull Run, Fredericksburg, and Chancellorsville spread the impression that all good news emanated from the theater where Lee and his army operated. For the rest of the war, with the single exception of Chickamauga, Confederate field armies won no major victories anywhere west of the Appalachians. Under these circumstances, and with the additional importance of Richmond as a psychological, industrial, and governmental colossus, it should come as little surprise that Confederates fixed their gaze, as well as their hopes, on Virginia.

This brings us to the fourth and most important question: Did the Seven Days significantly alter the trajectory of the war? The foregoing discussion surely suggests that the answer is an emphatic yes. In terms of broad-scale impact, the Seven Days stands as one of the great turning points of the conflict. Counterfactual speculation about what might have happened under different circumstances is usually pointless, but Lee’s rise to command offers a clear exception. It is easy to imagine the war taking a very different path if Joe Johnston had escaped his wound at Seven Pines. He almost certainly would have retreated into Richmond, there to be besieged and eventually conquered by McClellan. The avalanche of bad news from other theaters already had threatened to smother Rebel hopes for victory; the loss of the capital might well have destroyed the Confederacy. Lee’s successful defense of the city reversed a downward trend and virtually guaranteed a much longer and increasingly revolutionary struggle. Had McClellan captured the city, the war likely would have ended in the summer of 1862—with slavery largely intact and relatively little destruction across the South.

Much of the campaign’s impact already was apparent by the end of July 1862. Observers on both sides could see the imprint of McClellan’s and Lee’s decisions on political connections to military affairs, on debates over war aims and policy (including emancipation), on civilian morale and attitudes, and on the diplomatic front. During that second summer of the war, people could only guess at some of the longer-term effects that stand out in retrospect. Students of the war should use that retrospective advantage to appreciate the full context within which the campaign was waged and the astonishing range of its immediate and far-reaching influence.

Gary W. Gallagher taught for more than 30 years at Penn State University and the University of Virginia. His most recent book is The Enduring Civil War: Reflections on the Great American Crisis. (LSU Press, 2020).