One of the rare things upon which the country’s liberal and conservative factions can agree in these roiling times is the vision of Abraham Lincoln as America’s ideal president. Republicans claim him as their scion—although, granted, the Republican Party is a much different animal today than it was in the 1860s—while the Democrats claim kinship over his more liberal precepts and actions. It is highly unlikely that we would hold our 16th president in such general and unquestioned reverence were it not for the lifelong efforts of two young men who knew Lincoln intimately, and attended to him daily.

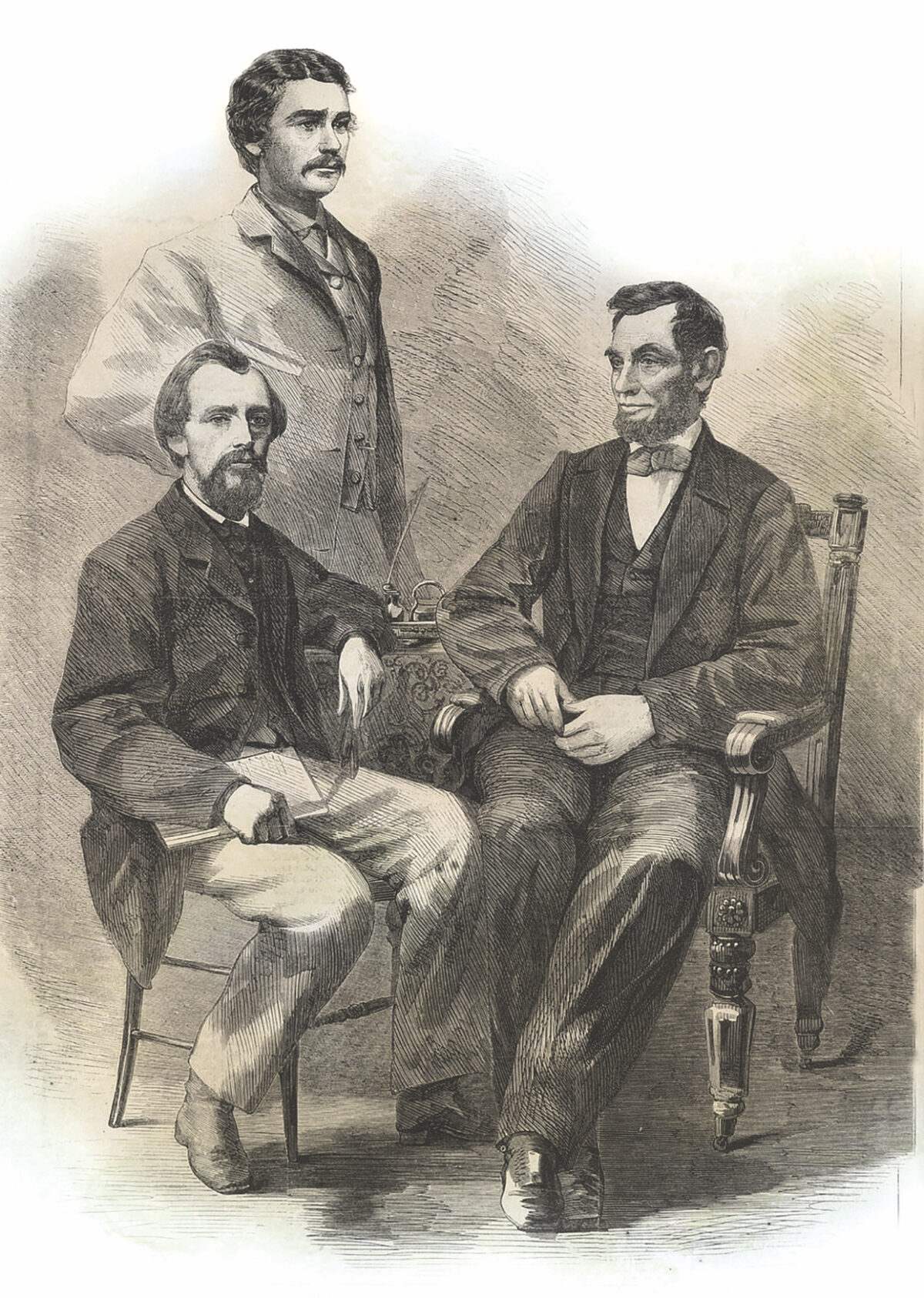

John Nicolay and John Hay served throughout Lincoln’s tragically curtailed presidency as his personal secretaries. Both men were highly intelligent and remarkably capable, fiercely devoted to and protective of their boss. Living in the White House with the Lincoln family, they were, as Joshua Zeitz writes in his 2014 book Lincoln’s Boys: John Hay, John Nicolay and the War for Lincoln’s Image, “both literally and figuratively, closer to the President than anyone outside his immediate family…performing the roles and functions of a modern-day chief of staff, press secretary, political director, and presidential body man.”

In addition to handling the tremendous amount of clerical work their positions generated, Nicolay and Hay also acted as Lincoln’s personal doormen, screening all visitors to the White House. They called Lincoln “the Tycoon,” although never to his face; for his part, Lincoln looked upon the two as surrogate sons, referring to them as “the boys.” Although both shared Lincoln’s confidence and friendship, Nicolay was the closer to the president. When 11-year-old Willie Lincoln died in 1862, it was to Nicolay whom Lincoln first turned for solace.

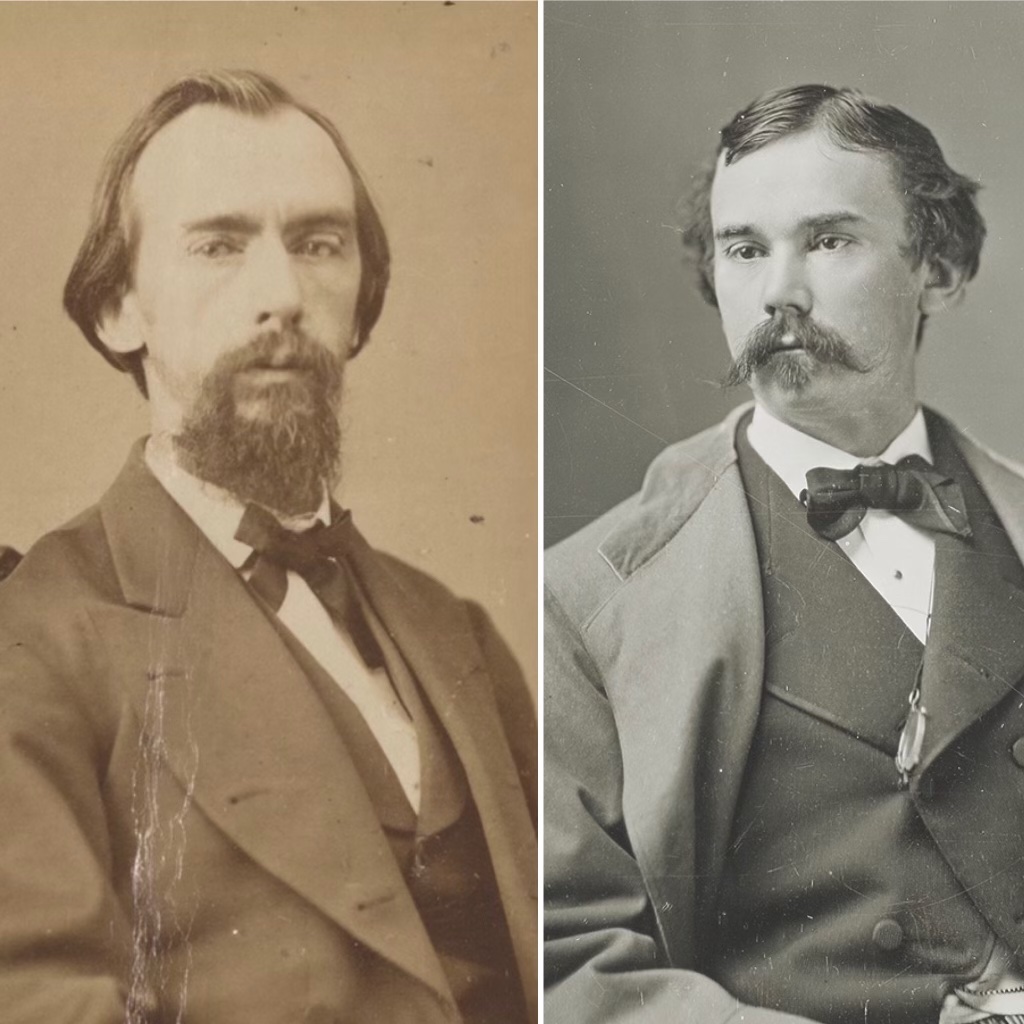

Born in Bavaria in 1832, John George Nicolay came to Illinois with his family, still a child. While in his early twenties, he worked at, and soon became owner of, the Pittsfield (Ill.) Free Press. It was while working at the paper that he met Hay, who was attending a private academy in Pittsfield. Though Nicolay was six years older, the two immediately became fast friends.

Nicolay sold the paper in 1856 to take a position as clerk for the Illinois secretary of state in Springfield. Lincoln often visited the office on political business, and the two became acquainted. Impressed with the young man’s intelligence and ability, Lincoln hired Nicolay as his personal secretary when he ran for the presidency. Nicolay then convinced the candidate to take Hay aboard as assistant secretary.

John Milton Hay grew up in Warsaw, Ill. After graduating from Brown University, he returned to Illinois, entering his uncle’s law practice. As it turned out, Lincoln’s office was next door—the two became acquainted even before Nicolay recommended the young law clerk to the future president.

Hay and Nicolay could not have had more disparate personalities. Hay was clever and outgoing, and enjoyed Washington society and the companionship of others. He was boyish in appearance and manner, and a journalist at Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address referred to him as “handsome as a peach.” Nicolay, on the other hand, was gaunt, dour, and abrupt, and—in the words of William Stoddard, who joined the White House staff as an assistant secretary in 1861—“decidedly German in his manner of telling men what he thought of them.” Still, Nicolay and Hay always found common ground. That was key in their ability to bond in shaping, burnishing and preserving their former chief’s memory after his April 1865 assassination.

In the years following the Civil War, recording their experiences with the late president for posterity proved a daunting task. While his death inspired many Americans to canonize him, there were those who tended to see Lincoln in a darker light. Some, especially those in government, viewed him as a poor leader. Massachusetts Governor John Andrew referred to him as “essentially lacking in the quality of leadership,” while Charles Francis Adams, diplomat, editor, and son and grandson of presidents, eloquently commented, “I must affirm without hesitation that in the history of our government, down to this hour, no experiment so rash has ever been made as that of elevating to the head of affairs a man with so little previous preparation for the task as Mr. Lincoln.”

Horace Greeley, a newspaper editor and 1872 presidential candidate, agreed, stating that Lincoln failed to take advantage of several opportunities to end the war. Lincoln’s former law partner, William Herndon, was frequently off the mark in his characterization of his late friend. He was merciless in pillorying Mary Todd Lincoln; and when relating “facts” about Lincoln’s life, he often erred, in one instance falsely claiming that Lincoln’s mother was a “bastard.”

Many Northerners felt as Greeley did, blaming Lincoln for the four years of turmoil that killed some three-quarters of a million Americans. In the defeated South, which had begun busily fabricating the seductive myth of the “Lost Cause” soon after the surrender, the late president’s image suffered immeasurably worse. Not surprisingly, to the bitter Southerners, Lincoln was the devil incarnate, a tyrant cruel beyond measure.

Family aside, Lincoln’s staunchest defenders were his former personal secretaries. Hay, in fact, considered the late president “the greatest character since Christ,” and he and Nicolay set out to ensure that Lincoln’s legacy would shine for coming generations.

They were fortunate to have had immediate access to Lincoln on a daily basis, as well as to the documents that crossed his desk. Indeed, there were several occasions on which the boys penned the overworked Lincoln’s missives for him, submitting them for his signature.

Better still, they had developed a strong relationship with Lincoln’s eldest son. Robert Todd Lincoln found would-be biographers’ negative characterizations of his father irksome at best and slanderous at worst. At one point, he wrote in frustration to Lincoln’s executor, Supreme Court Justice David Davis, “Mr. William H. Herndon is making an ass of himself.” Robert commissioned Hay and Nicolay to write an accurate biography of his late father and made Lincoln’s personal papers available to the two. No one else would have access to these papers until 1947. As it turned out, the confidence Robert placed in them was more than amply rewarded.

Both Nicolay and Hay were, in the words of one chronicler, “witty and prolific letter writers, observant and incisive diarists,” and their efforts culminated in a massive but highly readable 10-volume biography of their late boss. It took them decades. Simply titled Abraham Lincoln: A History, the biography first appeared in serial form in the Century magazine in 1886, and was not published as a complete set until 1890.

By then, Americans were anxious to put the Civil War behind them. Revisionist histories were voguish at the time, promoting national reconciliation, rather than the representation of historical facts. This trend caused Nicolay and Hay great consternation; they had no intention of sugar-coating the recent schism. Their biography pulled no punches in placing the causes of, and responsibility for, the war exactly where the authors saw it. They presented their martyred subject against the backdrop of a war that was fought primarily over slavery, and not, as the South would have it, states’ rights only.

It is a truism that there is no such thing as an objective history. The Lincoln whom Hay and Nicolay chronicled and offered to the public represented the man as they saw and knew him. “Theirs,” Zeitz wrote, “was a deliberate project of historic creation.” Abraham Lincoln is arguably the single most written-about personage in American history; yet the Lincoln whom we know—or, believe we know—today, and with whom future generations will become acquainted is a direct result of the efforts of “Lincoln’s boys.”