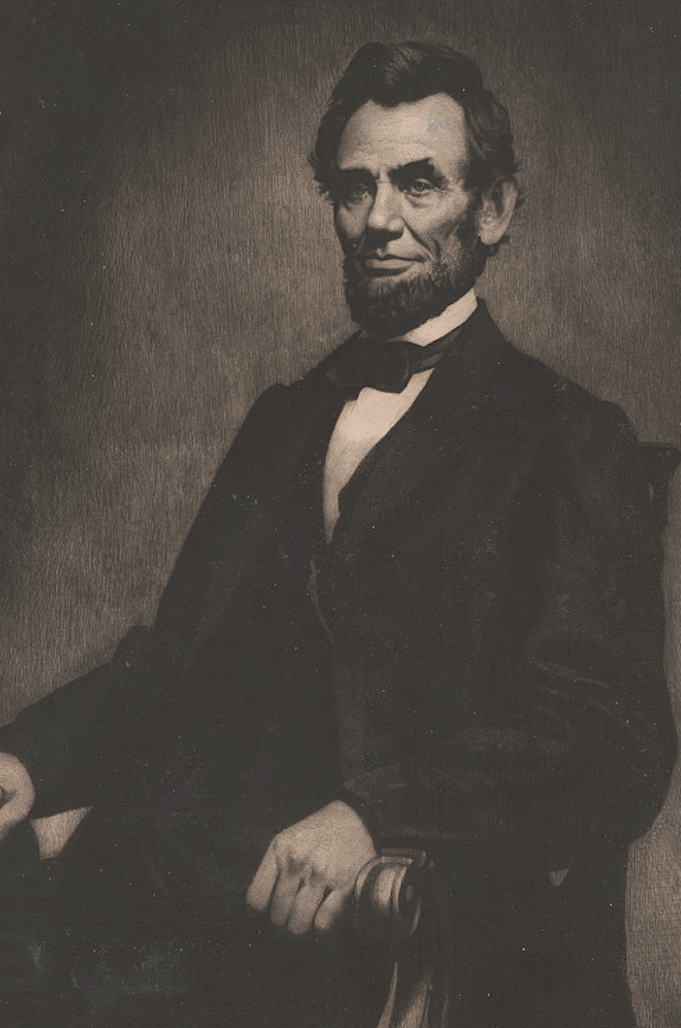

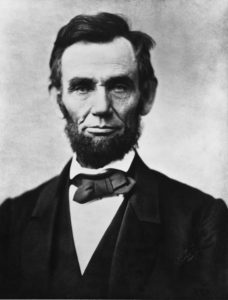

Abraham Lincoln was the 16th president of the United States of America, who successfully oversaw the Civil War to preserve the nation. He played a key role in passage of the Thirteenth Amendment, which officially ended slavery in America. Murdered by John Wilkes Booth, Lincoln became the first U.S. president to be assassinated. Prior to his election as president in 1860, he had successful careers as a lawyer and politician in Illinois, serving several terms in the state legislature and one in the U.S. House of Representatives.

Facts

Lincoln also holds the distinction of being the only U.S. president to receive a patent; in 1849, he designed a system for lifting riverboats off sandbars.

Born

February 12, 1809, in Hodgenville, Kentucky

Died

April 15, 1865, at Petersen House, Washington, D.C.

Presidential Term

March 4, 1861–April 15, 1865

Spouse

Major Accomplishments

- 16th President of the United States

- Led the United States through the Civil War

- Issued the Emancipation Proclamation

- Wrote the Gettysburg Address

More STories About Abraham Lincoln

Quotes from abraham lincoln

Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this continent, a new nation, conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.

The Gettysburg Address, November 19, 1863

“A house divided against itself cannot stand.” I believe this government cannot endure, permanently half slave and half free. I do not expect the Union to be dissolved — I do not expect the house to fall — but I do expect it will cease to be divided. It will become all one thing or all the other.

June 16, 1858, Springfield, Illinois

Biography

Abraham Lincoln’s Youth

Abraham Lincoln was born on Sinking Springs Farm near Hodgenville, Kentucky, on February 12, 1809, to Thomas and Nancy Hanks Lincoln. He was named for his paternal grandfather. His birthplace is believed to have been a 16-foot by 18-foot log cabin, which no longer exists. Lincoln had a sister, Sarah, who was two years and two days older than he was, and a younger brother, Thomas, who died in infancy.

When Abraham was two, the family moved to nearby Knob Creek Farm. Five years later, the family moved again, to the wilderness on Little Pigeon Creek in Indiana. On October 5, 1818, his mother died, reportedly of “milk sickness,” caused by drinking milk from cows that have eaten a poisonous, blossoming plant called snakeroot. Thomas Lincoln remarried a year later, to Sarah Bush Johnston, a woman of Elizabethtown, Kentucky, whom he had known for many years. She had three children by a previous marriage, Elizabeth, Matilda, and John. Although Abraham and his father were never close, Sarah and nine-year-old Abraham formed a loving relationship that continued throughout their lives. She encouraged him in his attempts to educate himself, which he did by borrowing and studying books.

Lincoln Moves To Illinois

In 1830, when Abraham was 21, the family moved to Illinois. He performed odd jobs and took a flatboat of goods to New Orleans. At New Salem, he was a partner in a store at that failed and would be many years paying off the last of the store’s creditors, an obligation he referred to as “the National Debt.” Elected captain of a militia unit during the 1832 Black Hawk War—an election he later would say pleased him more than any other—he saw no combat, but he met the man who would change his life in many ways: John Todd Stuart.

Lincoln Becomes A Lawyer

Stuart and Lincoln both ran for the Illinois General Assembly that year; Stuart won, Lincoln didn’t. Two years later, however, both men won election. The more experienced Stuart, known as “Jerry Sly” for his skills at management and intrigue, showed Lincoln the ropes and loaned him law books, that he might study to become an attorney. In 1836, Lincoln received a license to practice law. He would go on to establish a respectable record as an attorney and was often hired by the Illinois Central Railroad.

Lincoln won reelection to the General Assembly in 1836, 1838, and 1840; among his accomplishments was a major role in getting the state capital moved to Springfield. He did not actively seek the post again after 1840, but won the popular vote in 1854; however, he resigned so he would be eligible for election to the U.S. Senate.

Lincoln Goes To Congress

In 1846, he was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives, where he gave the infamous “Spot” speech about the war that had begun with Mexico. He demanded President James K. Polk reveal the exact spot on which American blood had been shed, starting the war, and whether that spot was on American or Mexican soil.

The speech may have been a reflection of words his “beau ideal” statesman, Speaker of the House Henry Clay, had uttered in a speech Lincoln heard while visiting Lexington, Kentucky, on the way to Washington. Or it may have been a partisan maneuver—Lincoln was a Whig, Polk a Democrat—to ingratiate himself with the older Whigs in Washington. Popular opinion in most of the country supported the war, and newspapers around the country ridiculed him as “Spotty Lincoln.” He did not run for reelection to Congress in 1848, but for the first time in its history, his home district elected a Democrat instead of a Whig. He spent the next several years focusing on his law practice to support his growing family.

In the Illinois legislature, he’d served with Ninian Wirt Edwards of Springfield, the son of a former governor of Illinois. Edwards’ wife was the former Elizabeth Todd of Lexington, Kentucky. When her younger sister, Mary, came from Lexington Lincoln became smitten; as Ninian observed, “Mary could make a bishop forget his prayers.” Although facts are unclear, an understanding apparently developed between Lincoln and Mary, but they parted ways in December of 1840 or January of 1841. Over a year later, a friend brought them back together, and they wed November 4, 1842.

There have long been stories—begun by Lincoln’s long-time law partner, William Herndon—that Lincoln had previously been engaged to Ann Rutledge in New Salem and had nearly lost his mind when she died. However, she was betrothed to another and there is no verifiable evidence of any romantic relationship or understanding between her and Lincoln. Neighbors’ stories indicate Lincoln did take her death hard. He was always prone to fits of “melancholia”—depression—and one state legislator claimed Lincoln told him he wouldn’t carry a pocket knife for fear he’d use it to harm himself.

Family Life With Mary Todd Lincoln

Abraham and Mary Lincoln would produce four children: Robert Todd, named for Mary’s father; Edward (Eddie) Baker, named for a close friend; William (Willie) Wallace, named for Dr. William Wallace, who had married Francis, another Todd sister, and had become close friends with Lincoln; and Thomas (Tad), named for Lincoln’s father who had died two years earlier. Eddie died in 1850, Willie in 1862, and Tad in 1871. Only Robert lived to adulthood; the last of his descendants would die in 1985, ending the Abraham Lincoln family line. (Learn more about Mary Todd Lincoln)

Although Lincoln did not seek office himself during these years, he remained active in the Whig Party, counseling candidates who sought his advice and occasionally responding to speaking requests. In 1854, he essentially was campaign manager for Richard Yates, who was running for the General Assembly. Lincoln did not want to be elected to that body again himself because he knew the legislature would be electing a new U.S. Senator during its coming term, to fill the position of James Shields, who had moved to the Minnesota Territory. (At that time, nearly 60 years before the Seventeenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution provided for direct election of senators by the voters, they were chosen by each state’s legislature.) By Illinois law, sitting state legislators could not be elected to the U.S. Congress—and Lincoln desperately wanted to become the new senator, a position he said he would prefer over being president. Regardless, eventually he reluctantly agreed to run . He won more votes than any other candidate but resigned in order to keep his senatorial chances open.

His hopes were dashed again when the vote for senator was taken in 1857. Despite a strong start, he saw that a Democrat would be elected unless the Whigs united, so he threw his supporters’ votes to another candidate.

Since the early 1830s, abolitionists—those who adamantly favored abolishing slavery everywhere in the United States—had become increasingly strident. Even many people like Lincoln who did not approve of slavery also did not approve of the sectional divisiveness engendered by the abolitionists. Slaveholding states—virtually all of which were in the South—in responding to abolitionists’ attacks defended the “peculiar institution” of slavery more vociferously, and sectional tensions grew.

A Nation Dividing

In 1854, a passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act allowed residents of any new states admitted to the Union to decide for themselves whether or not the state would be free or slaveholding. In the 1857 Dred Scott decision the Supreme Court ruled that neither the Declaration of Independence nor the rights guaranteed by the Constitution applied to Negroes and never had. As a result of these events, many who had disassociated themselves with abolitionists’ agitation began drifting into their camp, and the abolitionists movement intensified.

Like his father, Lincoln opposed slavery; however, he also deplored abolitionists’ activities because they threatened to cause a schism in the nation. In regard to “slavery agitation” he said, “In my opinion, it will not cease, until a crisis shall have been reached, and passed. ‘A house divided against itself cannot stand'”

Notes for a speech he delivered in Ohio clearly articulate his opinions on the slavery issue in the 1850s:

“We must not disturb slavery in the states where it exists, because the Constitution, and the peace of the country both forbid us – We must not withhold an efficient fugitive slave law, for the constitution demands it – But we must, by a national policy, prevent the spread of slavery into new territories, or free states, because the constitution does not forbid us, and the general welfare does demand such prevention.” (Abraham Lincoln, (September 16–17, 1859), Notes for Speech in Kansas and Ohio)

The Whig Party to which he had always been dedicated was dying. By 1854, a new party, the Republicans, was taking its place. Comprised of old Whigs, disaffected Democrats and members of the Native American Party (“Know-Nothings”), its unifying theme was opposition to the institution of slavery. In 1856, Lincoln joined the new party.

The Lincoln Douglas Debates

In 1858, he engaged in a legendary series of debates across Illinois with the author of the Kansas-Nebraska Act, Sen. Stephen Douglas. The five-foot, four-inch Douglas—”the Little Giant”—and the lanky, six-foot-four Lincoln faced off over the issue of expanding slavery beyond the states where it currently existed. Lincoln carefully made a distinction between slavery where it existed and its expansion into new territories and states. The debates drew national attention, and Lincoln was invited to speak in other states.

The national attention he received resulted in the Republican Party making him its presidential candidate in the 1860 election. On the divisive matter of slavery, the Republican platform supported prohibiting slavery in the territories but opposed interfering with it in the states where it already existed.

The Democratic Party split, producing two candidates, Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois and John C. Breckinridge of Kentucky. An independent Constitutional Union Party ran John Bell of Tennessee as its candidate. Two other independent parties formed but failed to carry a single state in the fall elections. Breckinridge carried the Deep South and two slave-holding East Coast states, Maryland and Delaware; Bell won Kentucky, Tennessee and Virginia; Douglas only carried Missouri. Lincoln won every Northern state, California and Oregon; although he failed to win a majority of the popular vote in this drawn-and-quartered election, he won enough electoral votes—180 compared to 123 for all his opponents combined—to become the 16th president.

President Abraham Lincoln

On December 20, nearly three months before Lincoln would take office (presidential inaugurations occurred in March at that time), South Carolina officially seceded from the Union. It was soon joined by all states of the Deep South. They feared the rise of this new, sectional party that opposed expansion of slavery. If the peculiar institution was not allowed to spread, slaveholding states would be outnumbered, and they feared losing the political power that protected slavery.

For weeks, president-elect Lincoln said nothing as state after state renounced its compact with the United States, though it is questionable whether anything he said would have halted the secession movement. Previous presidents under whom secession was threatened—Andrew Jackson and Zachary Taylor—had both said they would send troops to force states to remain in the Union but never had to take that action. Lincoln, faced with the reality of losing a section of the country, felt he did have to after Confederate guns fired during the Battle of Fort Sumter, South Carolina, on April 12, 1861.

The Civil War Begins

He called for 75,000 troops to suppress the Southern rebellion. Virginia, Arkansas and Tennessee then seceded, refusing to fight their fellow Southerners and claiming Lincoln had overreached his authority because Congress was not in session and therefore could not authorize a war.

The new president knew little of military affairs, but just as he had educated himself as a youth, he began a self-education in the art of war, checking books of military history out of the Library of Congress. From this reading, and perhaps from an innate sense of what needed to be done, he at times seemed to understand better than some of his generals that destroying the enemy’s armies was more important than capturing the Confederate capital.

He endured outright insubordination from one commander, Major General George B. McClellan, in charge of the largest Union army. Lincoln said he’d hold McClellan’s horse if it would help to win the war, but once he determined “Little Mac” was too cautious to win much of anything, he removed him. Not until March of 1864, when he placed Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant in charge of all Union armies, did Lincoln find a general in whom he had trust. Grant had previously won major victories at the Siege of Fort Donelson, Battle of Vicksburg, and Battle of Chattanooga.

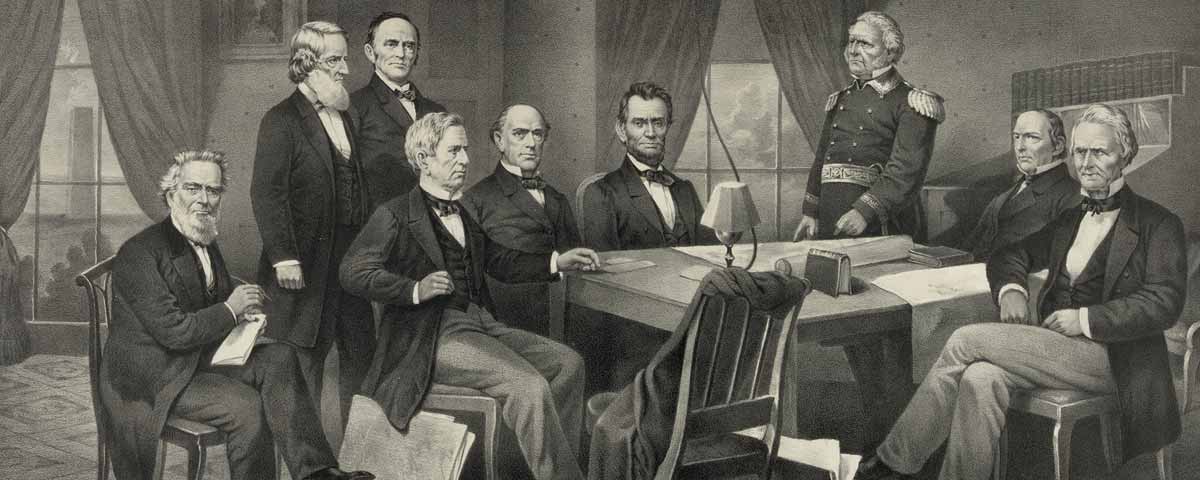

Lincoln, in choosing his cabinet, had selected those men he felt most capable of handling the duties of the posts he asked them to fill. Some of them had hoped during the last election that they would be filling the chair of the presidency. Historian Doris Kearns Goodwin called the Lincoln Cabinet “A Team of Rivals.” His willingness to work with men, some of whom he knew had a low opinion of him—at least initially—says much about Lincoln’s character and his determination to do whatever it took to preserve the Union.

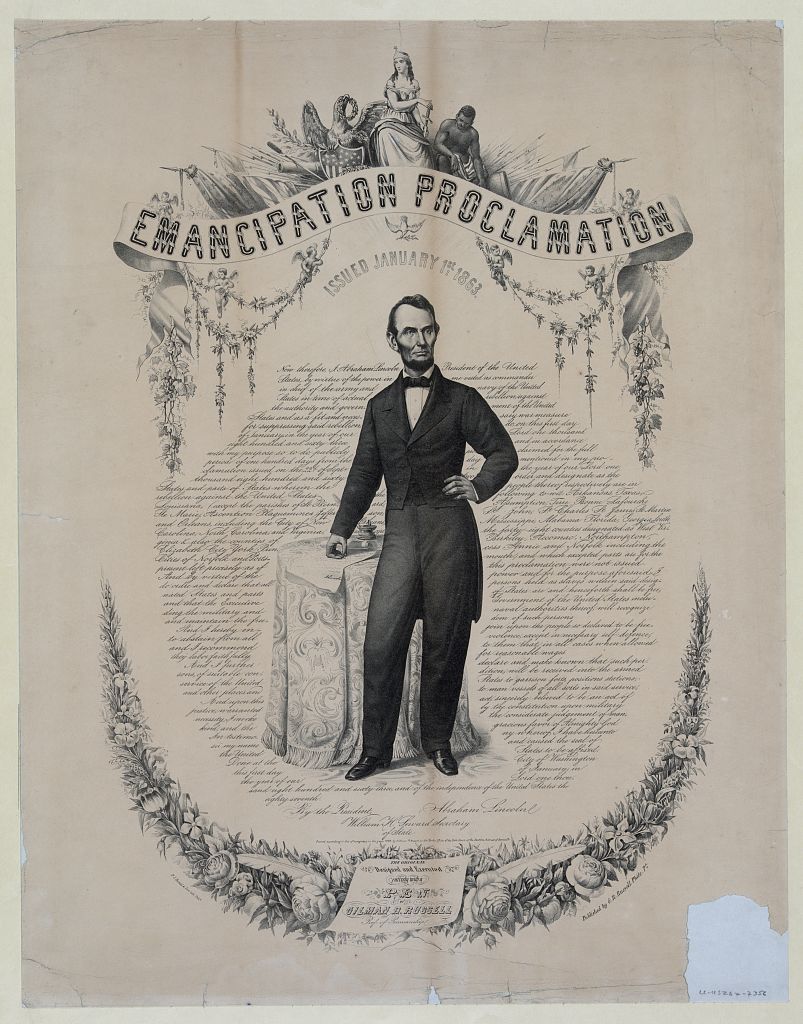

The Emancipation Proclamation

Following the Battle of Antietam, on January 1, 1963, Abraham Lincoln announced his Emancipation Proclamation. It granted freedom to slaves—but only to those in the areas still in rebellion, which didn’t recognize his authority. It was a war measure, meant to prevent European recognition of the slaveholding Confederacy, and it shifted the war from one to preserve the Union to one that would both preserve the Union and end slavery.

Other controversial war measures taken by Lincoln and his administration included infringing on some Constitutional rights, including suspending habeas corpus and shutting down newspapers that opposed the war. He signed the bill admitting West Virginia as a state of the Union, although it had been formed from Virginia without the permission of the state’s government at Richmond, which many, including half of his cabinet members, believed was a violation of Article IV, Section 3 of the Constitution. Nevada was admitted at least in part to provide another pro-Union state.

Lincoln Reelected In 1864

In presidential elections of 1864, Lincoln believed he would not be reelected. The war had dragged on for over three years, draining the treasury. Major battles, like the Battle of Shiloh, the Battle of Antietam, the Battle of Fredericksburg, the Battle of Chancellorsville, the Battle Gettysburg, and the Battle of Chickamauga, had each produced over 10,000 casualties, far beyond anything the nation had experienced in previous wars. Grant’s current campaign in Virginia had already suffered nearly 50,000 losses. Radical abolitionists in the North were upset with him for not pressing harder on the slavery issue.

The Democratic Party, banking on war weariness, was running George McClellan, the former general, as their candidate, under the slogan, “The Union as it was, and the Constitution as it is,” and pledging a truce with the Confederacy. Indeed, Lincoln might have lost his bid for re-election, and with it the war, had Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman not captured Atlanta in early September, giving the Union a major victory. Other contributing factors included Lincoln allowing soldiers in the armies to vote in their camps, something that had never been done before. The Democrats themselves made several missteps that hurt their chances. Lincoln won reelection and in his second inaugural address called for, “malice toward none, with charity for all,” attempting to set the stage for a reconciliation with the South.

He had personally experienced the “divided house” he’d once warned of. All but one of his wife’s half-siblings fought for the Confederacy or married men who did, and one of her full brothers became a Confederate surgeon. Only three of her sisters in Illinois and their husbands remained firmly with the Union.

The End Of The Civil War

On April 9, 1865, General Robert E. Lee surrendered the largest Confederate army to Grant following the Appomattox Campaign and the Appomattox Courthouse, virtually ending the war. Lincoln, asked what should be done with the citizens of the Confederate capital at Richmond, Virginia, responded, “I’d let ’em up easy, let ’em up easy.”

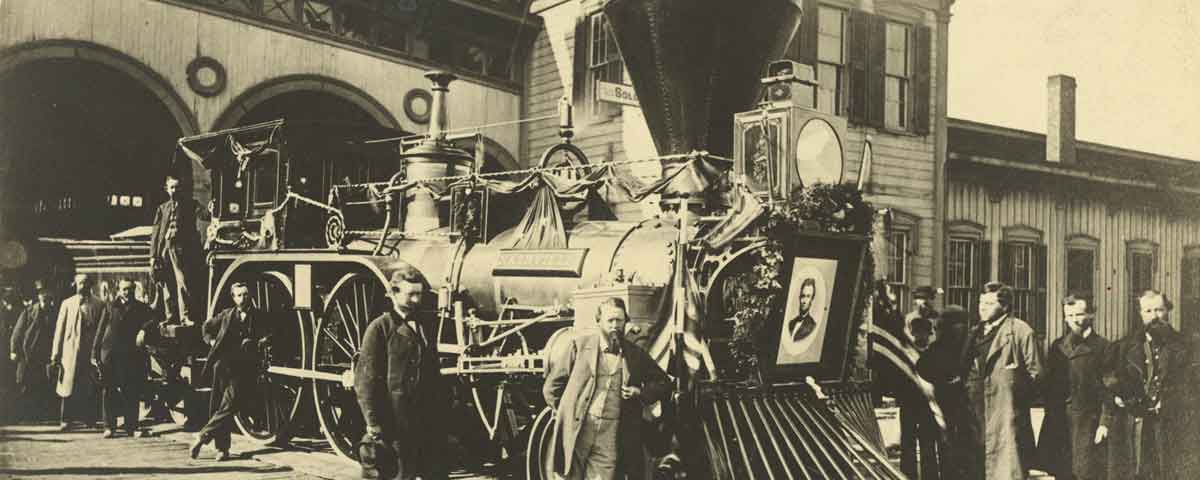

Abraham Lincoln Assassinated

With the light of victory clearly breaking over the horizon, Lincoln and Mary went to Ford’s Theater on the night of April 14 to see the comedy, “Our American Cousin.” During the performance, an actor and staunch Confederate sympathizer named John Wilkes Booth slipped into the presidential box and shot Lincoln in the head. The president died the following morning. Within 24 hours, not a shred of black crepe was to be had in the nation’s capitol as homes, stores and government buildings were draped in mourning. Even some Southern newspapers condemned the assassination.

Lincoln was laid to rest in Springfield, Illinois. In 1876, a counterfeiting gang attempted to steal his body, to exchange it for their master engraver, who had been imprisoned. The plan was thwarted, and when the president’s body was placed in a new tomb in 1901, some 4,000 pounds of cement were poured on top of his coffin to prevent any future attempts.

The popular image of Lincoln has changed many times. He is beloved as the Great Emancipator and the Savior of the Union, but many people, particularly in the South, regard him as a tyrant and a dictator. He has been accused of being racist, though his views were in keeping with those of most Americans of his times. During his presidency, association with black leaders such as Frederick Douglass seem to have made his racial views more enlightened than those of most mid-19th-century Americans.