“I kept on until I arrived at the East Room…before me was a catafalque on which was a form wrapped in funeral vestments. Around it were stationed soldiers…there was a throng of people…weeping pitifully. ‘Who is dead in the White House?’ I demanded… ‘The President…killed by an assassin…’ A loud burst of grief…woke me from my dream.”

–Abraham Lincoln, recounting a dream shortly before his assassination in 1865.

Because of the telegraph, news of President Abraham Lincoln’s shooting on April 14, 1865, and death on the 15th spread quickly, and the country—both in the North and South—was in shock. The nation and government turned to Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, who agreed to run the nation until Vice President Andrew Johnson was sworn in. He met with an assembly from Illinois that pleaded Lincoln be laid to rest in Springfield, his “adopted home” in the first state to recognize his “greatness.” Stanton then appointed a Committee of Arrangements (made up of Illinois citizens) to determine the transportation of President Lincoln’s remains from Washington, D.C., to their final resting place.

Distraught, Mary Todd Lincoln also turned to Stanton and the nation for her husband’s burial. Her only request was that Willie Lincoln, who had died in the White House in 1862, at the age of 12, be disinterred and make the trip home with his father and be buried beside him.

George Harrington, assistant secretary of the Treasury, was in charge of the funeral preparations, commencing with the building of the catafalque—a raised platform on which a deceased person lies in state. In disregard to expense, Commissioner of Public Buildings Benjamin B. French designed the catafalque and erected it in the East Room of the White House.

As foreshadowed in his dream, Lincoln lay in state in the East Room of the presidential mansion until the official funeral ceremony for family and government officials. Among those attending the service were the president’s personal cavalry escort; the leaders of the Northern Army and Navy—Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant and Admiral David Farragut; members of the Cabinet and Supreme Court; President Johnson; and former Vice President Hannibal Hamlin. Mary Lincoln and Secretary of State William Seward, convalescing from an attempted assassination also on April 14, were absent.

At the conclusion of the April 19 funeral, Lincoln left the White House for the final time.

Simultaneously throughout the country, both North and South, 25 million mourners would hear sermons about Lincoln delivered by local ministers.

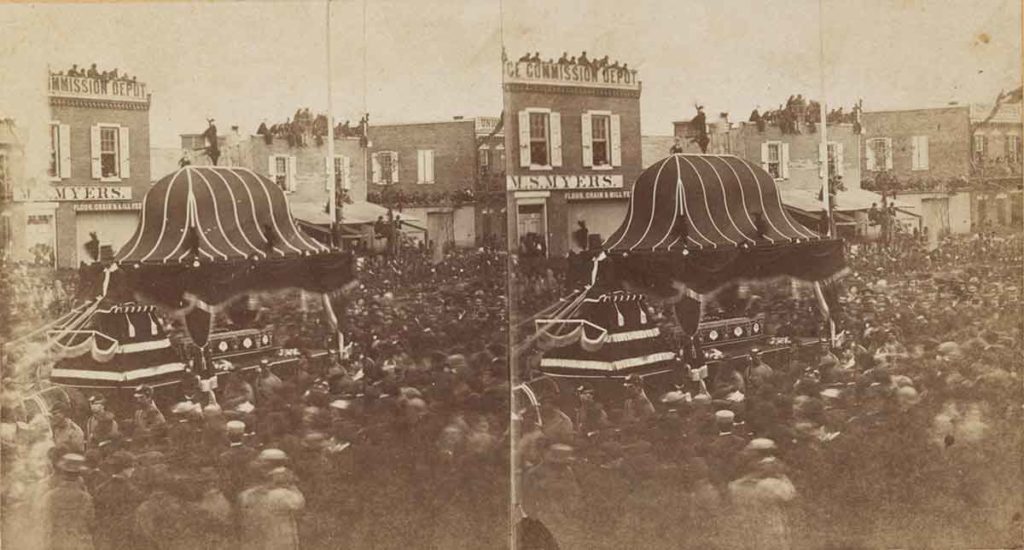

The Veteran Reserve Corps, composed of men who were no longer physically able to serve in front line positions, served as the official pallbearers for Lincoln’s coffin until it reached its final resting place. The soldiers lifted the flag-draped casket and placed it on a horse-drawn caisson. Arranged by Lincoln’s confidant Ward Hill Lamon, the slain president’s last procession was led by white horses and a detachment of United States Colored Troops. It proceeded up Pennsylvania Avenue to the Capitol “amidst the tolling bells and the firing of minute guns.” A riderless horse followed the casket with boots reversed in the stirrups. This was the first presidential funeral to feature such a horse, and it came to symbolize a warrior who would never ride again. The coffin was carried up the steps of the Capitol, beneath the very spot where six weeks earlier Lincoln had delivered his notable and inspiring Second Inaugural Address. Upon arrival at the Capitol, a brief service was given. Then Lincoln belonged to the people. He was the first president to lie in state at the Rotunda.

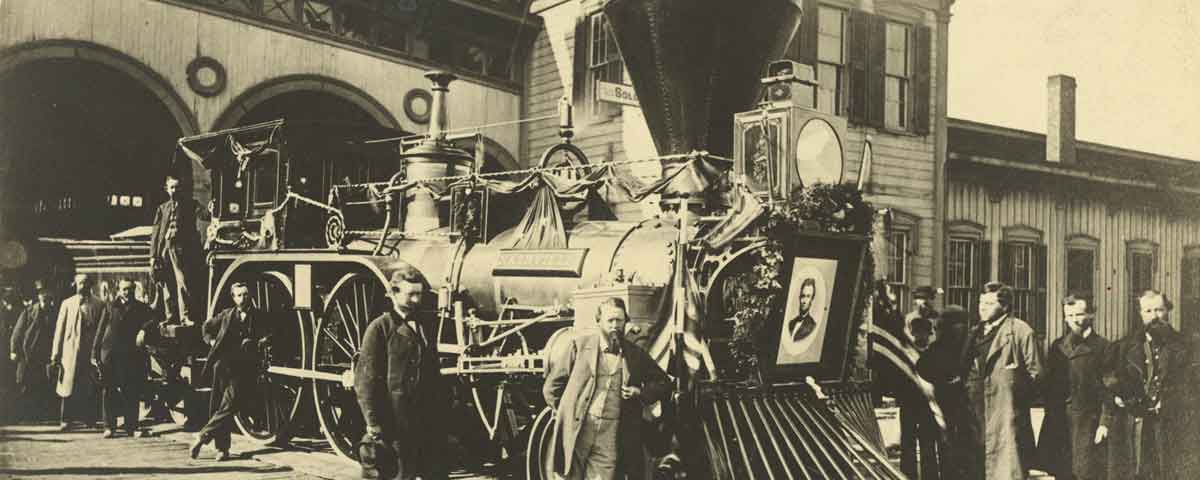

On April 21, at 7 a.m., an honor guard escorted Lincoln’s and Willie’s coffins to the train station. At approximately 12:30 p.m., the nine-car train pulled out, never traveling above 20 miles per hour to lend dignity to the mournful journey to Springfield.

Washington

On Friday, April 21, 1865, the Lincoln Special—as the train was known—draped in black garland and accompanied by an honor guard, left the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad depot in Washington, D.C., bound for Baltimore, 38 miles away. It was preceded by a pilot engine, to ensure the track was clear and to announce the arrival of Lincoln’s train. Both engines had portraits of Lincoln attached to their cowcatchers.

Baltimore

At Baltimore, a steady rain fell as approximately 10,000 people paid their respects to Lincoln’s body at the Merchant Exchange Building during a three-hour public viewing.

Harrisburg

A violent thunderstorm canceled the funeral procession in the Pennsylvania capital on April 21, and Lincoln was carried to the state house for an evening viewing. A viewing also took place the next morning. About 25,000 people saw the coffin in Harrisburg, and a crowd of 40,000 watched the hearse carried back to the depot.

Philadelphia

More than 30,000 mourners viewed the president’s body in the east wing of Independence Hall, where the Declaration of Independence had been signed. The first night’s viewing was by invitation only, and as the special guests departed, mourners were already gathering for the public viewing. For some, the wait lasted up to five hours.

New York City

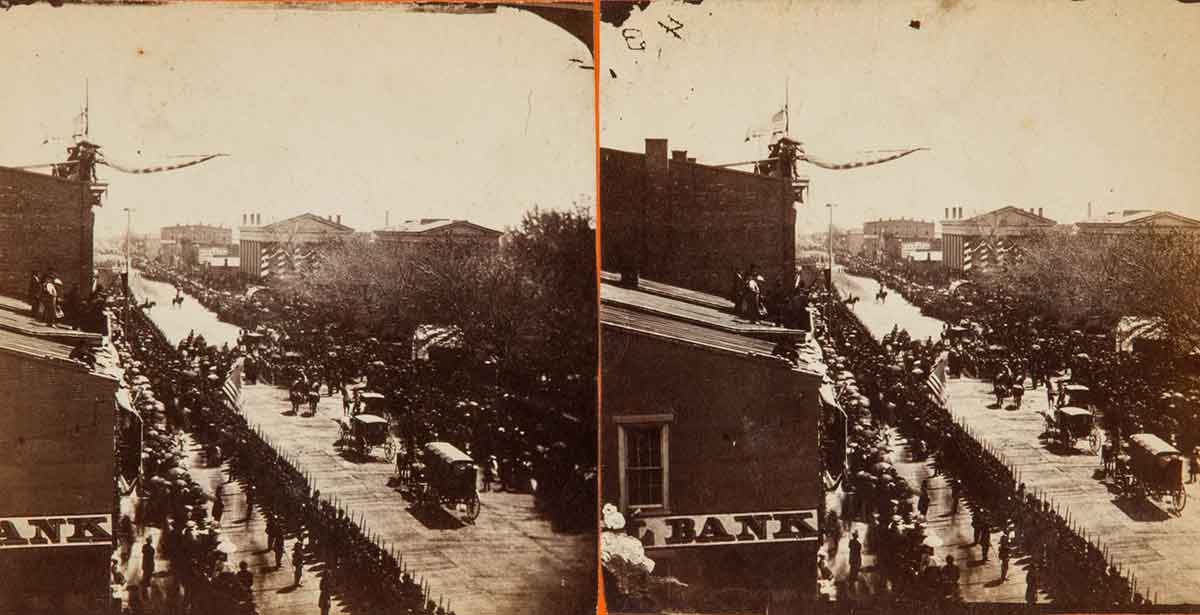

The clock at the train station in Jersey City, N.J., had been stopped at 7:20 a.m.—the approximate time of Lincoln’s death—but the train arrived on schedule at 10 a.m. Monday, April 24. The coffin was transported by ferry across the Hudson River to New York City and brought to City Hall. Viewing began at 1 p.m., and more than 50,000 people lined up to catch a glimpse of Lincoln’s remains. For four hours the next afternoon, 16 horses pulled a majestic 14-foot-long car carrying the coffin through the streets, as 75,000 citizens marched solemnly behind. Windows along the route were rented for viewing at up to $100 a person, and 6-year-old Theodore Roosevelt watched with his grandfather from one of those windows near Union Square.

Albany

As the train made its way up the Hudson River Valley to Albany, 141 miles from New York City, torches and lanterns lighted the train tracks. Entire populations of small towns gathered, no matter what the hour, to say goodbye and sing to their beloved president as his train rolled past. After arriving in Albany, the coffin was moved to the state house for public viewing, where locals offered their last respects. The next morning, newspapers brought word that assassin John Wilkes Booth had been tracked down and killed on April 26.

Buffalo

In Buffalo, the coffin was transported to St. James Hall on a catafalque drawn by six white horses in black harnesses. Former President Millard Fillmore and future President Grover Cleveland were among 100,000 mourners to file past the coffin. Unlike the previous stops, no formal procession took place since the city had already conducted a mock funeral and procession on April 19, not then knowing Buffalo was to be a scheduled stop.

Cleveland

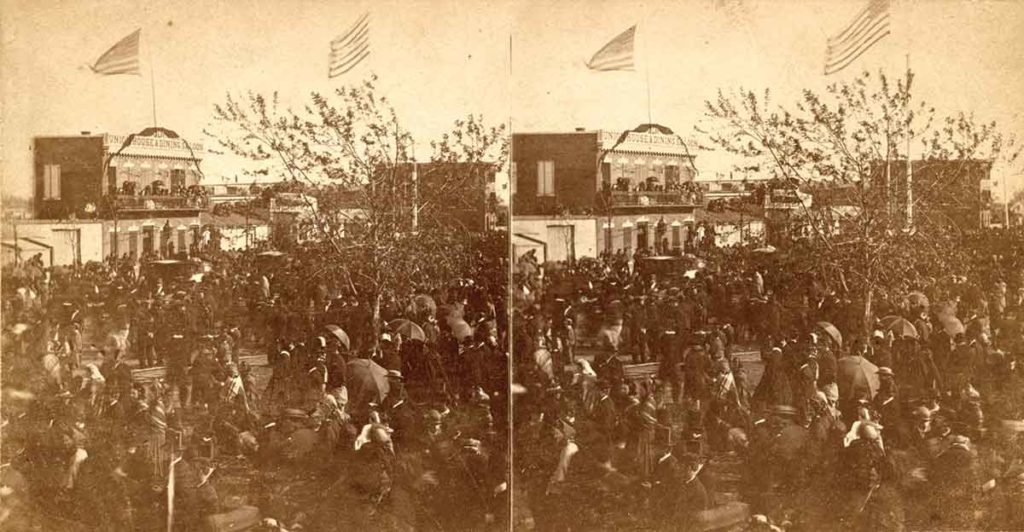

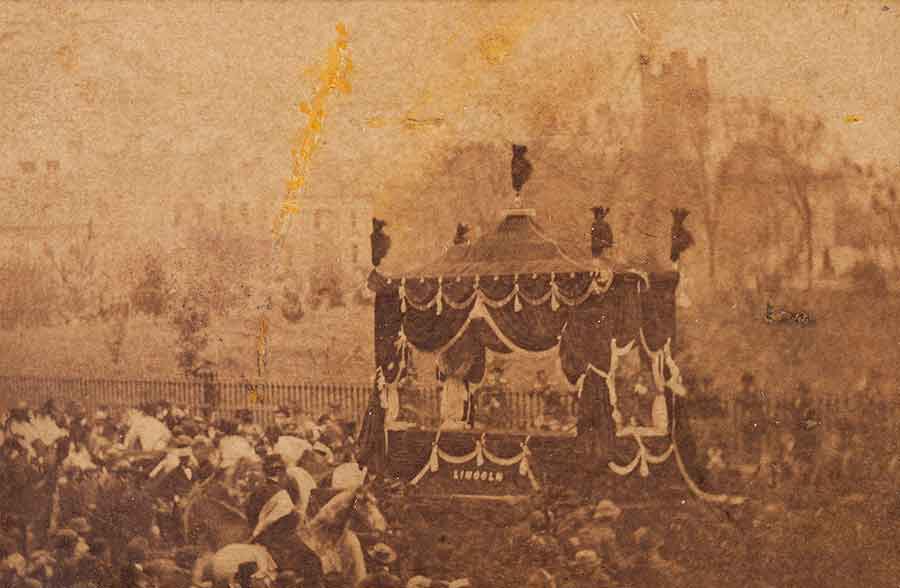

When Lincoln’s coffin arrived in Cleveland on April 28, it had been a full week since the Lincoln Special had bid farewell to Washington. It was carried from the Euclid Street Station to Public Square, and the outdoor venue allowed Cleveland’s leaders to erect a viewing pavilion. Despite torrents of rain, 180 mourners per minute filed past President Lincoln’s body. A visitor who had attended every funeral thus far claimed that the one in Cleveland was “by far the most magnificent.” Much like the small towns on the way to Albany, those across Ohio also presented heartfelt and poignant scenes. Recalled one newspaper account: “The flow of bonfires, torches and lanterns was common…people turned out en masse…heads uncovered and with saddened faces, gazing with awe upon the train…most of the coach and sleeping car lamps were extinguished, but the funeral car was fully lit…piercing the night as it passed by.”

Columbus

In Columbus, the train pulled in promptly at 7:30 a.m. on Saturday, April 29. As was now customary, the coffin was taken off the train for a procession and public viewing. The viewing in Columbus was at the rotunda inside the state capitol. The catafalque differed from all the others on the journey in that it lacked both columns and a canopy. Instead of lying in black velvet, it sank into a bed of flowers and low moss. In addition, carpet covered the floor to deaden the “shuffling and clicking of leather shoes.” By evening, the train had departed Ohio, headed for Indianapolis.

Indianapolis

Torrential rain doused the Lincoln Special upon its arrival in Indianapolis, forcing government officials to cancel a scheduled procession and devote the entire day of April 30 to a viewing at the Indiana State House. Late in the evening the train left for Chicago.

Chicago

On May 18, 1860, Lincoln was in Chicago when he won the nomination for president. When his body returned nearly five years later, Chicago’s farewell was comparable in size, length, and grandeur to New York City’s. The procession along packed streets wove around Chicago’s most prominent buildings, arriving at the courthouse four hours later. At 6 p.m. the doors were opened to the public for viewing throughout the night and the following day. Approximately 7,000 people passed by the coffin per hour. At 8 p.m., by the light of 3,000 torches, eight black horses drew the hearse back to the depot.

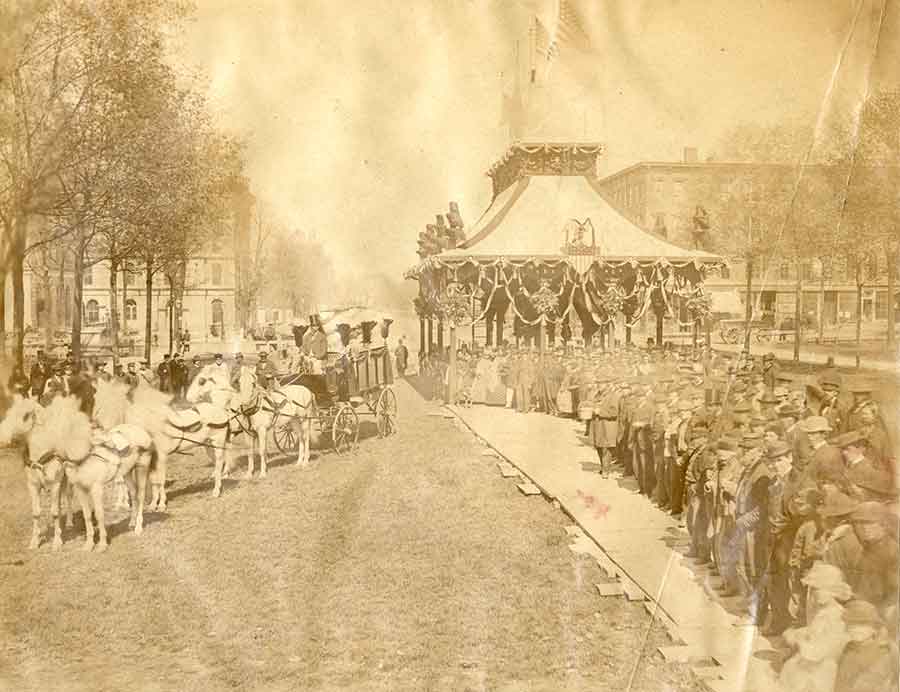

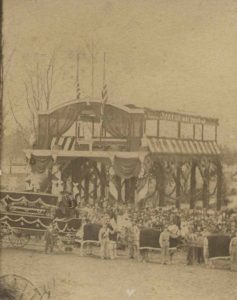

Springfield

On May 4, the nation’s 16th president would finally be laid to rest in his beloved hometown. The previous day, he had lain in state in the same state house room where he had recited his immortal “House Divided” speech in June 1858. Shortly before 10 a.m., the doors were opened for public viewing. Others gathered at the president’s home, where his horse, Old Bob, and his dog, Fido, had been brought from Washington.

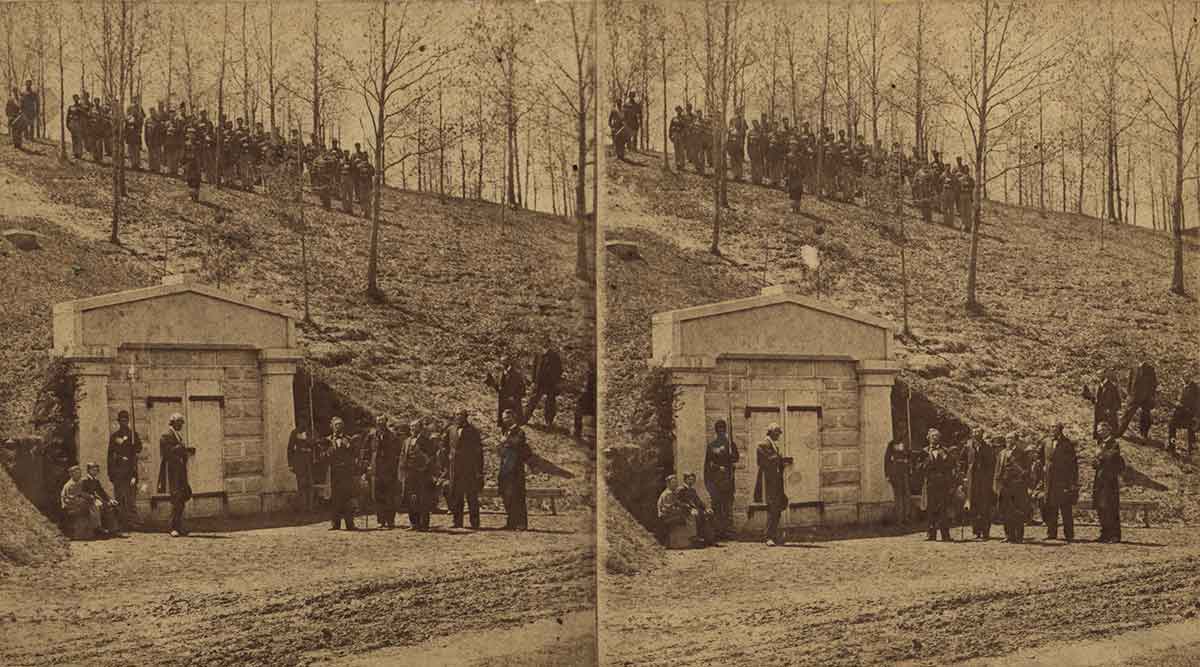

For the funeral, the city of St. Louis lent Springfield the exquisite hearse (above), finished in gold, silver, and crystal. Major General Joseph Hooker led the final procession to Oak Ridge Cemetery, where Lincoln’s coffin would be placed on a marble slab inside the tomb, along with that of his deceased son Willie.

Lincoln’s eldest son, Robert, and his cousin John Hanks represented the president’s family. (Mary, back in Washington, D.C., was still too distraught to attend.) Bishop Simpson delivered an eloquent funeral address and the Rev. Dr. P.D. Gurley read the benediction. At the end of the service, the tomb’s iron gates and heavy wooden doors were locked, with Robert given the keys.

“I am leaving you on an errand of national importance, attended, as you are aware, with considerable difficulties,” President-elect Abraham Lincoln told a zealous crowd on February 12, 1861, as he prepared to leave his adopted home state of Illinois by train, en route to his first inauguration in Washington, D.C. “Let us believe, as some poet expressed it, ‘Behind the cloud the sun is shining still.’ I bid you an affectionate farewell.” For the next four years, Lincoln did all he could do to keep a fractured nation together, tormented that nearly 700,000 soldiers on both sides of the Mason-Dixon Line would die in the process. Lincoln would never return alive to Illinois or his hometown of Springfield, slain by an assassin’s bullet on April 15, 1865. Throughout the 11-day funeral procession by train back to Springfield, where Lincoln was to be buried, clouds and rain were a constant reminder of the occasion’s solemnity for hordes of mourners along the way. But behind those clouds and rain, the sun did shine. There was hope at least that the United States, once on the verge of being torn in two, could begin to heal.