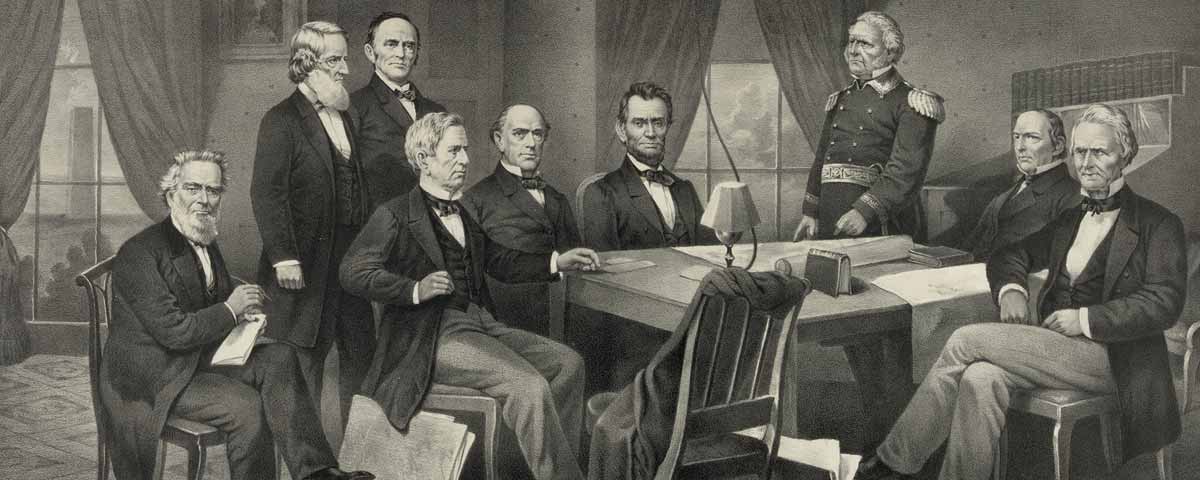

[dropcap]W[/dropcap]ith war clouds looming over Charleston Harbor as he assumed the presidency in March 1861, Abraham Lincoln had little time to determine whether conciliation with the South or a show of military force would be the appropriate response if fighting broke out. As expected, Lincoln received advice on several fronts, but the rookie president would ultimately be swayed by the counsel of one of his closest associates—Postmaster General Montgomery Blair.

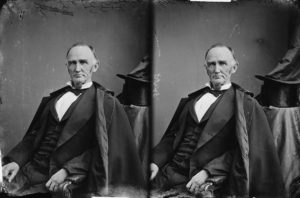

Blair was the only graduate of the U.S. Military Academy in Lincoln’s Cabinet, so his opinions on military matters carried great weight. More important, however, was that he belonged to one of the foremost political families in America. In 1861, it was Blair who would drive events not just in South Carolina, but also in Virginia and Missouri, in ways that profoundly shaped the course of the Civil War. He would be guided greatly by the similar threat of civil war the nation had faced during the Nullification Crisis nearly three decades earlier.

Lincoln was an outsider to Washington, but by 1861 the Blair family had been a major presence in the political life of the nation’s capital seemingly forever. The family patriarch, Francis P. Blair Sr., had become one of the most important players there during Andrew Jackson’s presidency. As a member of Jackson’s “kitchen cabinet” and, as an editor, one of the administration’s most zealous defenders in the press, Blair played a critical role in the organization of the Democratic Party to support Jackson’s political fortunes and mobilize support for his policies. The home he acquired across the street from the Executive Mansion during Jackson’s presidency—the “Blair House,” which he passed on to his son Montgomery in 1854—became a central gathering place for leading officials in the government. (In recognition of its prominent place in the nation’s history, in 1939 Blair House became the first building to receive recognition as a National Historic Landmark and shortly thereafter was acquired by the U.S. government to provide lodging for distinguished visitors to the capital.) But Blair’s loyalty to the Democratic Party was shattered in the 1840s and 1850s by the Southern minority’s efforts to control the government and dictate policy to the rest of the country—violating what he believed one of the bedrock principles of Jacksonian Democracy: the principle of majority rule.

Despite being a slave owner, Blair transferred his loyalties to the new Republican Party. He dedicated his family’s considerable talents and energy into making the Republican Party an effective vehicle for ensuring majority rule would prevail in the country. The most important of these in 1861 would be his sons Francis P. Blair Jr. (Missouri’s lone Republican in Congress) and elder brother Montgomery; daughter Elizabeth Blair Lee, a leading member of Washington society; and her husband, Union Admiral Francis Phillips Lee, Robert E. Lee’s cousin.

[quote style=”boxed” float=”left”]Despite being a slave owner, Blair transferred his loyalties to the new Republican Party.[/quote]

Lincoln was eager for advice from those with such a long record of service when he arrived in Washington in February 1861, facing “a task before me greater than that which rested upon Washington.” Seven slave states had seceded and eight others awaited events to determine their course. The central question was how to strike a balance between firmness and generosity in forging a policy to regain the Southern people’s consent to be governed by Washington.

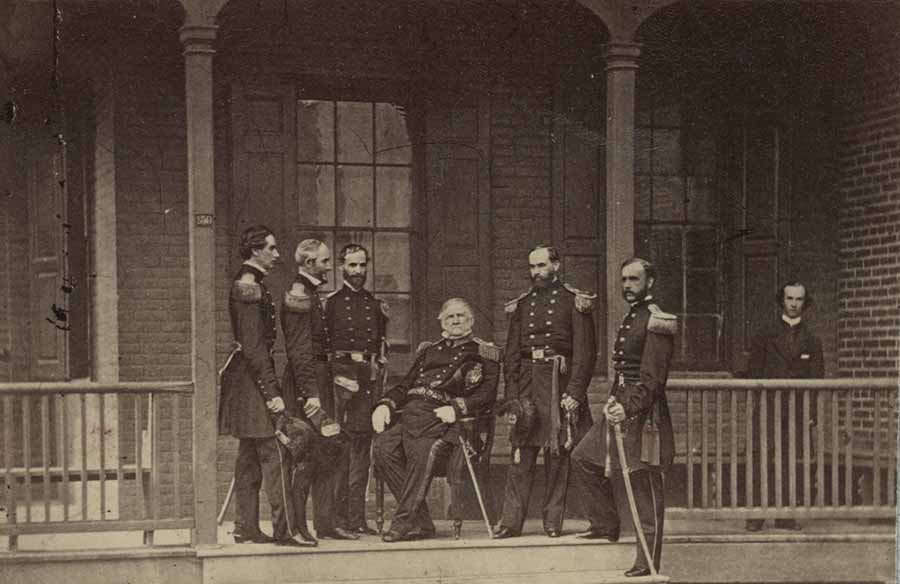

One man who no doubt had a clear view of the situation and how to address it was Bvt. Lt. Gen. Winfield Scott. His approach differed significantly from Montgomery Blair’s. Like the Blairs, Scott was a man of long experience in Washington’s ways, having been U.S. Army commanding general since 1841. Scott, however, never shared the Blairs’ enthusiasm for Andrew Jackson, personally and politically. Scott and the Blairs immediately were at odds over how to deal with the South as they attempted to influence the new president.

Scott believed the incoming administration should adopt a conservative, conciliatory course. To shape Lincoln’s thinking, Scott wrote to long-time political ally and kindred spirit, William H. Seward, whom Lincoln had just selected secretary of state. Scott’s March 3, 1861, letter argued a war to conquer the South would be neither cheap nor easy. He believed military victory over the Confederacy might be accomplished but was convinced it would take two or three years at the cost of more than 100,000 lives and “frightful” destruction. The end result would not be a “happy and glorious union” but, “Fifteen devastated provinces!…to be held for generations, with heavy garrisons, at an expense quadruple the net duties or taxes which it would be possible to extort from them, followed by a protector or an empire.” To avoid such a conflict, Scott urged Lincoln to “conciliatory measures.” If this was done, “we shall have not a new case of secession; but, on the contrary, an early return of many, if not all of the states which have already broken off.”

In his approach, Scott was influenced by his experiences as soldier and diplomat. His most significant experience came during the 1832-33 Nullification Crisis, when South Carolina hotheads challenged the federal government’s authority over the tariff issue. Scott, commanding the U.S. garrison at Charleston during that crisis, believed the conflict had been resolved because it never reached the point where shots were actually fired. Scott had encouraged interaction between his men and Charleston’s population to foster mutual good will and impress upon them the federal government’s benevolence, which he believed mitigated President Jackson’s belligerent tone and was critical to the administration’s ability to reach a crisis-resolving compromise.

Scott found Lincoln inclined to adopt a “watchful waiting” policy and was gratified with Lincoln’s extending an olive branch to the South in his inaugural address. Lincoln’s commitment to a policy of conciliation and restraint toward the South, however, rested on his expectation that his resolve would not be tested. The crisis over the Federal garrison at Fort Sumter wrecked that assumption. It also gave the Blairs an opening to steer the president’s thinking to a point more in line with their own.

[quote style=”boxed” float=”left”]Scott believed the incoming administration should adopt a conservative, conciliatory course.[/quote]

Blair believed the Nullification Crisis had been successfully resolved not by compromise and conciliation but because Jackson made it crystal clear to the South Carolinians that they faced serious consequences if they persisted in their course. The Nullifiers had acted as they did because they refused to believe the federal government possessed the will and determination to stand up to them. Jackson’s demand from Congress for a Force Bill enabling him to march an army into South Carolina and his unabashed glee at the prospect of hanging their leaders—which Blair enthusiastically endorsed and encouraged in the party newspaper—made clear this was a serious mistake.

It was a message that resonated with many Republicans, not least Lincoln, who understood that he led a coalition of former Democrats, Whigs, and Know-Nothings who disagreed on many points. What led them to form the Republican Party and held them together was a belief that for far too long the Northern majority had let itself be bullied and blackmailed into making concessions to the minority South.

[dropcap]L[/dropcap]incoln did not want war and believed the Union could be restored peacefully without compromising Republican principles. The key factor in Lincoln’s thinking was the “silent” Unionist majorities he believed had been cowed by secessionist minorities. As he saw it, the first step toward a peaceful reconstruction was keeping the eight states of the upper South in the Union. Once this was done, it would be only a matter of time before Unionists in the cotton states, alarmed about their isolation from their Upper South brethren, would rise up, overthrow the secessionists, and return their states voluntarily to the Union.

Yet to keep the Upper South in the Union it seemed paramount that the new administration refrain from actions that suggested using force to coerce the Lower South back into the Union. The situation at Fort Sumter destroyed Lincoln’s hopes to avoid having his resolution tested. He naturally turned to Scott and to his dismay was advised to surrender the fort. To do so, Scott argued, would facilitate voluntary reconstruction by cooling Southern passions and reassuring Southern masses of the good will of the Federal government. Moreover, Scott saw “no [practical] alternative but a surrender….[W]e cannot send the third of the men in several months…necessary to give them relief.”

The Blairs saw the matter differently. They were convinced secessionists believed Northerners weak and spineless, which the policy of restraint reinforced. Even before Lincoln took office, Montgomery Blair had bluntly advised him, “The real cause of the trouble arises from the notion generally entertained in the South that the men of the North are inferiors….They swell just like the grandiloquent Mexicans. And I really fear that nothing short of the lesson we had to give Mexico…will ever satisfy the Southern Gascons.”

As Lincoln pondered what to do about Fort Sumter on March 11, Francis P. Blair Sr. made his appearance at the Executive Mansion. He told Lincoln that “the surrender of Fort Sumter was virtually a surrender of the Union unless under irresistible force” and used such strong language that he asked his son to personally apologize to Lincoln if he felt he had been disrespectful. After hearing from the Blairs and Scott, Lincoln asked the members of the Cabinet to submit their opinions in writing.

Scott’s ally, Seward, echoed the general’s view. Secession, he argued, could “be banished…only in one way, and that by giving time for it to wear out.” If the fort could not be held without risking a fight, then Seward believed it must be evacuated. “Deny to the Disunionists any new provocation,” he urged, “Enable the Unionists in the Slave States to maintain, with truth and with effect, that the claims and apprehensions of the Disunionists are groundless.”

Montgomery Blair completely disagreed. He laid out what the Blairs believed was the lesson of 1833, telling the president that evacuating the fort would “convince the rebels that the administration lacks firmness and will…so far therefore from tending to prevent collision will ensure it.” “Every hour of acquiescence in this condition of things,” Blair contended, strengthened the rebels “and their claim to recognition as an independent people. . . The action of the President in 1833 inspired respect, whilst in 1860 the rebels were encouraged by the contempt they felt for the incumbent of the Presidency.”

Ultimately Lincoln decided to risk a “collision” and approved a plan—conceived by Francis Phillips Lee—to resupply Sumter. Before it could arrive, the Rebel batteries ringing Charleston Harbor opened fire April 12. Fort Sumter surrendered two days later.

Lincoln responded to Sumter’s fall by calling for 75,000 volunteers to overcome “combinations too powerful to be suppressed by the ordinary course of judicial proceedings.” As men rushed to the colors, the question of what to do with them again brought the Blairs into conflict with General Scott.

Scott remained convinced a war to conquer the South would neither be short nor easy. Even if the North triumphed, Scott believed it could do so only through a massive military effort inflicting such horrific destruction that the worst passions of both sections would be unleashed. “Invade the South at any point,” he warned Lincoln, “I will guarantee that at the end of the year you will be further from a settlement than you are now.”

[quote style=”boxed” float=”left”]Fort Sumter gave the Blairs an opening to steer the president’s thinking to a point more in line with their own.[/quote]

Instead, Scott intended to impose “a complete blockade of the Atlantic and Gulf ports” combined with “a powerful movement down the Mississippi to the ocean, with a cordon of posts at proper points…to envelop the insurgent States.” The movement on the Mississippi would take place after “four months and a half of instruction in camps.” Scott’s objective was to employ economic pressure to convince Southerners of secession’s folly, sparing the nation the destruction and polarization of a full-scale invasion. “Cut off from the luxuries to which the people are accustomed; and…not having been exasperated by attacks made on them,” Scott predicted, “The Union spirit will assert itself; those who are on the fence will descend on the Union side, and I will guarantee that in one year from this time all difficulties will be settled.”

The Blairs believed in a quicker, easier way. They shared Scott’s desire to avoid a long, bloody war and that Unionists were in the majority in the South. But they believed Scott was fundamentally wrong-headed to believe that time worked for the Union by cooling passions in the South. “General Scott’s system,” Montgomery Blair argued in a May 16 letter to Lincoln, “arises from the constitution of his mind & is but a continuation of the compromise policy….He does not comprehend the true theory of this contest and for that reason cannot adopt wise measures.”

Time, Montgomery and his family were convinced, actually worked against the Union. Putting off a confrontation with secessionist leadership would confirm the impression of Northern weakness that decades of compromising and making concessions to the slave state minority had impressed on the minds of the Southern people. Moreover, it would enable them to strengthen their hold over the South and suppress Unionist sentiments that the Blairs were certain a majority held. Indeed, Montgomery went so far as to assure Lincoln that prompt action by Union military forces “will now be hailed with joy by the people of the south everywhere and it can be given with a very inconsiderable part of the force at our command by a forward movement.”

For Lincoln, this was an appealing argument—not only did he possess the impatience for results characteristic of politicians, the analysis also had the benefit of being rooted in assumptions central to the Republican Party’s worldview, which Lincoln had played a critical role in articulating. Thus, Lincoln decided, weeks before the “On to Richmond” banner began to appear in the New York Tribune and over the protests of Scott and other military men, to promote Irvin McDowell brigadier general and appoint him commander of a newly organized Department of Northeastern Virginia, whose only purpose was to produce a field army for operations against the Rebels at Manassas Junction, Va. (One thing Scott and the Blairs did agree on in early 1861 was the desirability of having Robert E. Lee at the head of any army the United States government might place in the field. To the dismay of both luminaries, the interview between Francis P. Blair Sr. and Lee that took place at Blair House failed to persuade Lee to accept the honor.) Though dubious about the prospects of throwing an effective army together in such a short period, McDowell understood his appointment meant Lincoln wanted action before the April volunteers’ 90-day enlistments expired and went to work preparing operations against Confederate forces gathering around Manassas Junction.

[dropcap]I[/dropcap]n addition to Fort Sumter and the question of taking the offensive in Virginia, the Blair family prevailed over Scott on other issues. Few states were more precariously balanced in early 1861 than the critical Border State, Missouri. Its residents were mostly loyal to the Union, but the state legislature was dominated by Breckinridge Democrats and Missouri Governor Claiborne Fox Jackson believed his state must “stand by her sister slave-holding States, in whose wrongs she participates and with whose institutions and people she sympathizes.” In the aftermath of Lincoln’s election, Colonel William S. Harney, commander of the Department of the West headquartered at St. Louis, followed Scott’s lead by adopting a conciliatory policy toward state authorities. His efforts seemed to validate the assumptions that shaped Scott’s approach, as both he and the commanding general were gratified by the overwhelming election of Unionists to Missouri’s state secession convention, which adjourned March 22, 1861, without even bringing secession to a vote.

[quote style=”boxed” float=”left”]The Blairs were convinced secessionists believed Northerners weak and spineless.[/quote]

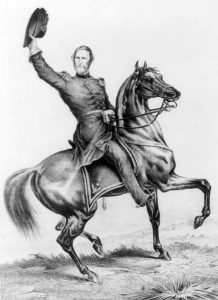

Less happy were Republican Rep. Francis P. Blair Jr. of St. Louis, and Nathaniel Lyon, an Army captain with no sympathy for aggrieved slave-owners’ complaints. Blair pulled strings to get Lyon in command of the St. Louis Arsenal. Lyon was just the kind of military man the Blair family wanted. Like their beloved General Andrew Jackson, Lyon had unbending Unionist convictions and little patience for the secessionist desires of Southern slaveowners. More important, Lyon agreed with Blair that secessionists believed the federal government lacked the nerve to firmly assert its authority. He believed this idea must be crushed.

The only way to do this, Lyon and Blair believed, was to act with uncompromising firmness toward the Missouri government, backing that up with a “whiff of grapeshot.” Despite the action—or lack of action—of Missouri’s convention, Blair and Lyon were intensely dissatisfied with Harney’s conciliatory approach that fostered an image of Northern timidity. Unsurprisingly, Blair and Lyon felt vindicated in their view by Governor Jackson’s refusal to obey Lincoln’s call for troops after Fort Sumter, which the governor decried as “illegal, unconstitutional…in its objects inhuman and diabolical.”

When Jackson took control of the St. Louis police and mobilized the pro-Southern state militia, Lyon and Blair responded by distributing arms to St. Louis Unionists (principally filling their ranks from the city’s German population especially antagonized pro-Southern Missourians), and sending out armed patrols. To his and Blair’s dismay, when Harney found out about this, he stepped in and brought a halt to Lyon’s machinations. Blair responded by successfully petitioning Washington for Harney’s removal from command on April 21. Upon reaching Washington, however, Harney made the case for a conciliatory policy in a meeting with Scott, who promptly restored him to command in Missouri.

While Harney was gone, all hell broke loose. Blair attempted to convince William T. Sherman, who was in St. Louis after resigning as superintendent of the Louisiana State Military Academy, to take Harney’s place, but Sherman declined. Privately, Sherman declared, “I would starve and see my family want, rather than ask Frank Blair or any of the Blairs whom I know to be a selfish and unscrupulous set.”

Shortly thereafter, the Missouri militia established a camp on high ground overlooking the arsenal and named it Camp Jackson—after the current governor, not the former president. Lyon surrounded and captured Camp Jackson on May 10 and provoked a riot in St. Louis when he marched his prisoners through the city’s streets. The Missouri General Assembly in Jefferson City responded by pushing through a military bill strengthening the governor’s hand as a newspaper commented, “The name of Colonel F.P. Blair seems to strike terror to all—the Governor, the officers, and the Assembly.”

[quote style=”boxed” float=”left”]The Blairs believed Scott was fundamentally wrong-headed to believe that time worked for the Union by cooling passions in the South.[/quote]

Upon his return to St. Louis on May 12, Harney immediately moved to leash Lyon and promised Jackson that he would disband the Home Guard units that Blair had raised, or confine them to Jefferson Barracks, 10 miles south of St. Louis. Blair then confronted Harney with an order from Lincoln that gave him authority to raise units and impose martial law if he so chose. Harney also managed to reach an agreement with the commander of the state militia, Sterling Price, that Missouri would remain in the Union, but assume a position of neutrality in the coming military contest between the Union and the Confederacy. Blair and Lyon were furious. The former had already petitioned Washington for authority to remove Harney from command and got it. On May 30, he used it. Harney was relieved, this time for good. Lyon received promotion to brigadier general.

Although unable to save Harney, Scott still wanted to salvage his conciliation policy in Missouri and decided to give command of the region to Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan by extending his Department of the Ohio to include Missouri. By then, McClellan had clearly established he was a man who shared Scott’s belief in conciliation and had already proved himself capable of handling affairs in a far-flung department. More important, McClellan had an aura of success from victories his command won in western Virginia that would hopefully give him the ability to rein in Lyon.

But McClellan was too far away, with too much else on his plate, to rescue the cause of conciliation in Missouri. By the time McClellan learned of his command’s extension to Missouri on June 18, Blair and Lyon had already crossed the Rubicon in their dealings with Governor Jackson and his pro-Southern administration. A conference between Blair, Lyon, Price, and Jackson in St. Louis, convened in a last-ditch effort to salvage peace, collapsed on June 11 when Lyon made clear he would make no concessions to Jackson’s government and was prepared to use force to back up his position. In words that effectively encapsulated the sentiments of his Blair family allies, Lyon closed the meeting by declaring: “rather than to concede to the State of Missouri for one single instant the right to dictate to my Government in any matter however unimportant, I would see you, and you, and you, and you, and you, and every man, woman, and child in the State dead and buried. This means war.”

Lyon followed up the conference by leading Union forces he had raised in St. Louis 180 miles up the Missouri River to the state capital at Jefferson City. After seizing possession of the town and expelling Jackson’s government, Lyon chased the Missouri State Guard 50 miles northwest to Boonville, where it made a feeble stand before being routed on June 18. Jackson and his government fled to southwestern Missouri. Whatever prospect Missouri had for joining the rebellion was effectively killed. Lyon’s actions undoubtedly proved great comfort to the Blairs, as they seemed to validate their own assumptions about dealing with secessionists firmly. The bitter, bloody, and prolonged guerrilla war that subsequently engulfed Missouri, however, led many to wonder later if Harney’s had been the proper approach.

[quote style=”boxed” float=”left”]While Harney was gone, all hell broke loose.[/quote]

What happened a month later, however, was less happy. In northern Virginia, McDowell’s green army tested the Blairs’ belief that a quick demonstration of military might lead to the collapse of the rebellion. Unfortunately, the merits of the Lincoln–Blair strategy were not revealed. After a day-long battle at Bull Run on July 21, McDowell’s army was sent reeling back to Washington, hopes for a quick and easy end to the rebellion collapsed, and even the New York Tribune found its enthusiasm for what it called “the headlong ‘forward to Richmond’ school” significantly diminished.

The Blairs had advocated action and successfully—and relentlessly—pushed for it believing it would provide a quick resolution of secession. They would be proved mistaken: 1860 was not 1833. The bitter war that began in 1861 would take on a character that they neither anticipated nor wanted. In this, they were by no means alone.

Ethan S. Rafuse is professor of military history at the U.S. Army Command and General Staff College in Fort Leavenworth, Kan.