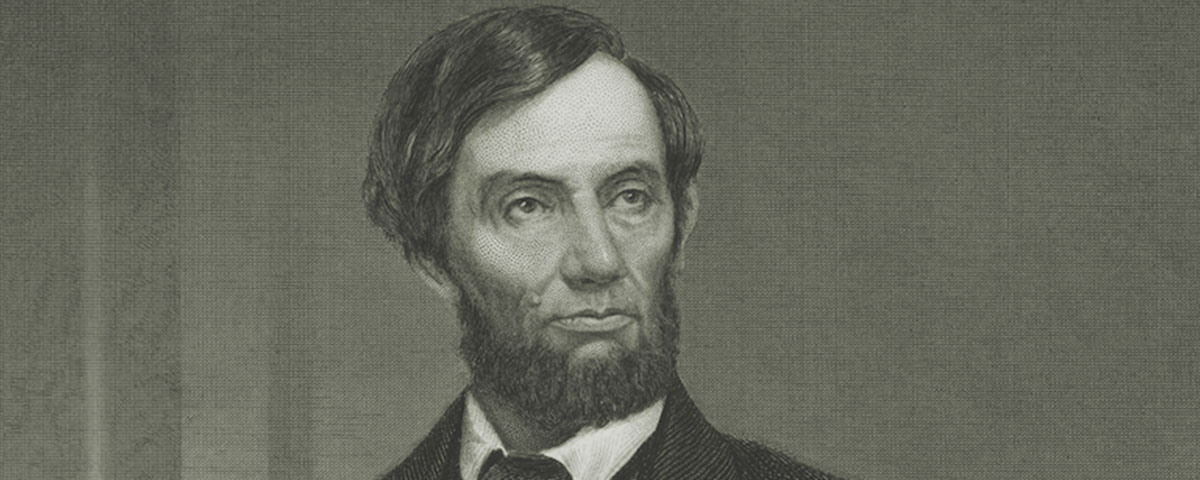

Author Ronald C. White explores an overlooked side of the 16th president

Abraham Lincoln is, justifiably, considered the greatest orator among all American presidents. But while his speeches are well-known, Lincoln’s lifelong habit of scribbling notes for his eyes only is less celebrated. Although many of these private notes were believed lost, several were found after Lincoln’s death by his secretaries John Nicolay and John Hay, who included them in their 10-volume Abraham Lincoln: A History. In Lincoln in Private: What His Most Personal Reflections Tell Us About Our Greatest President (Penguin Random House, 2021), Ronald C. White Jr. examines these surviving notes and invites readers to draw their own conclusions on how Lincoln felt about the great issues of his day and how he found the courage to ask his fellow countrymen to accept a new America.

ACW: Nicolay and Hay sometimes categorized Lincoln’s notes as fragments. Why?

RCW: Because many appear to begin or end in the middle of a sentence. Some end with a comma, indicating perhaps that Lincoln was called away to some other responsibility and never went back to that particular note. Notes written while he was in the White House are dated and are more formal, but they were still written only for his eyes.

ACW: Among the surviving note fragments is one written in 1848, during Lincoln’s single term in Congress, about a visit to Niagara Falls. Talk about how this panegyric to America’s first tourist attraction illuminates Lincoln’s private character and thought processes.

RCW: One of the book’s purposes is to show the wider range of Lincoln’s thinking and writing. We think of him as very logical and rational, which he was, but his visit to Niagara Falls prompted him to write about it in terms that I would call lyrical or poetic. It almost sounds like Henry David Thoreau. Lincoln scholars know about this passage because of a comment made by Lincoln’s longtime law partner in Springfield, Ill., William Herndon, who claimed, “I know Lincoln better than anyone.” Lincoln’s commentary about the Falls left Herndon unmoved. “He had no eye for the magnificence and grandeur of the scene—for the rapids, the mist, the angry waters and the roar of the whirlpool.” According to Herndon, Lincoln was “heedless of beauty or awe.” Obviously, Herndon didn’t know him so well, because the whole point of the fragment is to show Lincoln’s understanding of beauty and awe. That’s why I argue that there was a private Lincoln behind the public Lincoln we meet in the traditional biographies.

ACW: Another fragment that you chose to highlight offers practical advice for new lawyers. It does not address politics of the day but offers a window on Lincoln’s ambitions. You differ with biographers about when it was written. What was his intention?

RCW: Remember that Lincoln spent 24 years as a lawyer, only 12 as a politician. He returned from Congress in 1849 and was a fulltime lawyer for the next five years, spending much of his time traveling in Illinois’ 8th Judicial Circuit—an area twice the size of Connecticut. Many aspiring lawyers wanted to study with Lincoln, but as he was out on the circuit 175 or 185 days a year, I think he concluded he didn’t have time to tutor law students. This fragment tells us how Lincoln defines himself. It begins: “I am not an accomplished lawyer. I find quite as much material for a lecture in those points where I have failed as in those where I have been moderately successful.” This tells us a great deal about Lincoln’s character. He was an accomplished lawyer. Can you imagine a present-day leader, a CEO, a college president, saying, “I find quite as much material in points where I have failed?” He’s willing to say, “I learned from my own failures.” This is why Lincoln, although fully a 19th-century person, still speaks to us today.

ACW: In 1854, the passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act, which allowed settlers of those vast territories to vote on whether to allow slavery, jumpstarted Lincoln’s political career. How did Lincoln formulate his argument against Senator Stephen Douglas’ contention that “popular sovereignty” made the extension of slavery into new states constitutional?

RCW: We need to understand that Lincoln was on a journey toward an understanding of slavery. It started when he is 19 and traveled to New Orleans, where he was aghast at seeing how slaves lived. Fragments written between 1854 and 1860 allow us to chart his course, first as he began to understand the evil of slavery and what it does to African Americans and later on as he began to understand what a slave society does to white masters. While not very much of the language from the notes about Kansas-Nebraska made it into his speeches during the 1858 debates with Senator Douglas, they helped him think through how he was going to argue that slavery—and particularly allowing it in states joining the union—was wrong. A particularly famous fragment, tentatively dated July 1, 1854, Lincoln wrote: “If A can prove, however conclusively, that he may, of right, enslave B, why may not B snatch the same argument, and prove equally, that he may enslave A? You say A is white and B is black. Is it color, then; the lighter having the right to enslave the darker? Take care. By that rule, you are to be slave to the first man you meet with a fairer skin than yourself [your own].” In a very sly way, Lincoln turns the argument back upon itself.

ACW: Lincoln rarely let his emotions show in public, but the notes occasionally reveal his true feelings.

RCW: In the middle of the debates with Senator Stephen Douglas, Lincoln purchases a best-selling book by a Presbyterian minister from Alabama, the Rev. Frederick Augustus Ross, titled “Slavery Ordained of God,” which compiles all the biblical arguments being used to justify slavery. Lincoln never mentions this book in any of the debates with Douglas, but in a note to himself about Ross’ book, you can feel his anger rising. “As a good thing slavery is peculiar. It is the only good thing which no man seeks the good of for himself. Nonsense! Wolves devouring lambs not because it is good for their own greedy maws but because it is good for the lambs!!!”

ACW: Did Lincoln achieve what he wanted to in the debates?

RCW: The fragments do not include any comments about whether Lincoln believed he had been successful in the debates. However, we know that Lincoln made sure that 50,000 copies of the debate transcripts were published. In one sense, early on, Lincoln realized that it was a misfortune for him to be living and running for office in the same state as Douglas, after a while he realized what a benefit it was to be Douglas’ primary political opponent because the debates gave him fame that he had never had before. Douglas and the debates helped make Lincoln a national political figure.

ACW: Why is the 1858 fragment about the concept of democracy so important to the understanding of the evolution of Lincoln’s views on slavery and his decision to join the new Republican Party?

RCW: The story of this fragment is interesting in and of itself. Nicolay and Hay did not find it in their search of Lincoln’s papers. Rather, Mary Lincoln kept it and in 1875 gave it to Myra Bradwell, the first female lawyer in Illinois, after Bradwell helped Mary gain her release from the insane asylum to which her eldest son, Robert Todd Lincoln, had had her committed. “As I would not be a slave, so I would not be a master. This expresses my idea of democracy. Whatever differs from this, to the extent of the differences, is no democracy.” Assuming that the dating of this fragment is correct and that it was written in midst of the debates with Douglas, Lincoln had come to understand that the problem is not simply what slavery is doing to the slave, but what slavery is doing to the master.

ACW: After getting elected, Lincoln continued his practice of writing down his thoughts. One fragment that survives from the period between November 1860 and his inauguration in March 1861 refers to correspondence with future Confederate Vice President Alexander Stephens. Lincoln hoped to convince Stephens to oppose secession. How?

RCW: Lincoln and Stephens were colleagues and friends in the 30th Congress. Learning Stephens had spoken against secession, he thought, ‘Well, here is a moderate Southerner he could persuade to join his Cabinet.’ So he writes Stephens: “Do the people of the South really entertain fears that a Republican administration would directly, or indirectly, interfere with their slaves, or with them, about their slaves? If they do, I wish to assure you, as once a friend, and still, I hope, not an enemy, that there is no cause for such fears….You think slavery is right and ought to be extended; while we think it is wrong and ought to be restricted. That I suppose is the rub. It certainly is the only substantial difference between us.”

Stephens warns Lincoln that using military force to hold the Union together would be “nothing short of a consolidated despotism.” He implores the president-elect to “do what you want to save our common country.” Stephens quotes Proverbs: “A word fitly spoken by you would be like ‘apples of gold in pictures of silver.’” Lincoln does not reply, but in a fragment about preserving the Union, he writes about Stephens’ use of the metaphor. Lincoln muses that the reference could be used in an analogy about the Republic’s founding principles. Considered the more valuable metal, gold refers to the Declaration of Independence, which declares that all men are equal. Lincoln sees the reference to silver, secondary in value, as related to the Constitution. He concludes that the central principle of the American system is the Declaration’s demand for “liberty for all.” This he saw as a rebuke to slavery and led him to a final split with Stephens.

ACW: Although the date of when it was written is debated, one of the most notable fragments from Lincoln’s presidency appears to have been composed at a time of great crisis, possibly early September 1862. Can you explain the significance of the note, which has come to be known as the “Meditation on the Divine Will”?

RCW: In every aspect of Lincoln’s life, he’s on a journey. Scholars, however, have not delved deeply into his journey toward faith. In his youth, he rejected the evangelical fervor of the Baptist Church his parents attended. But his attitude toward religion changed as a result of life experiences, including his grief over the 1850 death of his second son, Eddie, who was 3½, and the 1862 death in the White House of his third son, Willie, who was 11.

He was also deeply affected by the crucible of the Civil War. Lincoln began to ask himself about the meaning of God in the midst of this horrible bloodshed. He begins more frequently to walk through Lafayette Park to New York Avenue Presbyterian Church for worship services. The minister, Phineas Densmore Gurley, I think is the missing person in the Lincoln story in Washington. After the Union defeat at the Second Battle of Bull Run on August 28-30, 1862, Lincoln convenes an emergency Cabinet meeting. Three of those present kept diaries, and one of them, Attorney General Edward Bates, wrote that Lincoln told the gathering that “he was struck with so much anguish he felt almost like hanging himself.” I think the president took the afternoon of September 2, 1862, and sat down to write this remarkable document.

One lingering question about Lincoln concerns his religion. In his Second Inaugural Address, he mentions God 14 times, quotes the Bible four times, and invokes prayer three times in 701 words. Some scholars have argued that this was not really Lincoln but a shrewd politician using the language of an audience he knew was religiously oriented. So how do we answer that question? I think the answer is contained in what Hay called the “Meditation on the Divine Will.” At the outset of this fragment, we hear the logical Lincoln: “In great contests each party claims to act in accordance with the will of God. Both may be, and one must be wrong. God cannot be for and against the same thing at the same time. In the present Civil War it is quite possible that God’s purpose is something different from the purposes of either party….I am almost ready to say that this is probably true—that God wills this contest, and wills that it shall not end yet.”

At the end of the fragment, Lincoln writes these remarkable words: “He could have either saved or destroyed the Union without a human contest…and having begun, He could give the final victory to either side on any day.” Do we understand why he never made this public? Lincoln is suggesting that God could give the final victory as easily to the Confederates as to the Union. I think this fragment is a remarkable signpost on Lincoln’s faith journey.

On March 4, 1865, the date of his Second Inaugural, no one is aware this document exists. In my Chapter 10, I compare side by side the major arguments of the Meditation and those of the Second Inaugural Address. A reader will see how absolutely parallel they are to each other. I think it’s one of the most significant fragments in helping us understand the private Lincoln behind the public Lincoln.

ACW: One of the most famous of Lincoln’s private writings is the document Lincoln wrote in August 1864, sealed, and had each Cabinet member sign. In it he acknowledged that it was unlikely he would be reelected and that it would be up to him and the Cabinet to work with the incoming administration to win the war before the new president was inaugurated. He quite dispassionately states that the new president will have campaigned and won on a platform that would result in Confederate independence. Was that in the fragments?

RCW: In the index of this book, all 111 surviving fragments are published in their entirety. One of them is the document Lincoln wrote in August 1864 after he received word from the Republican National Committee meeting in New York that he would lose the 1864 election. I’ve been privileged to see that document at the Library of Congress.

ACW: How has your study of Lincoln’s private writings affected you?

RCW: Very specifically, it influenced me to write notes for myself, sometimes at 3 a.m. on a pad I keep at my bedside. I’m very concerned that you and I are being so distracted by our addictions to our phones and computer screens and everything going on in our lives. What so amazes me about Lincoln is that in his busy life he took the time to write these notes. Do we take that kind of time? Or do our thoughts escape us? Lincoln did not want his thoughts to escape him. I have taken up the practice myself hoping my thoughts will not escape.

Nancy Tappan is America’s Civil War senior editor.