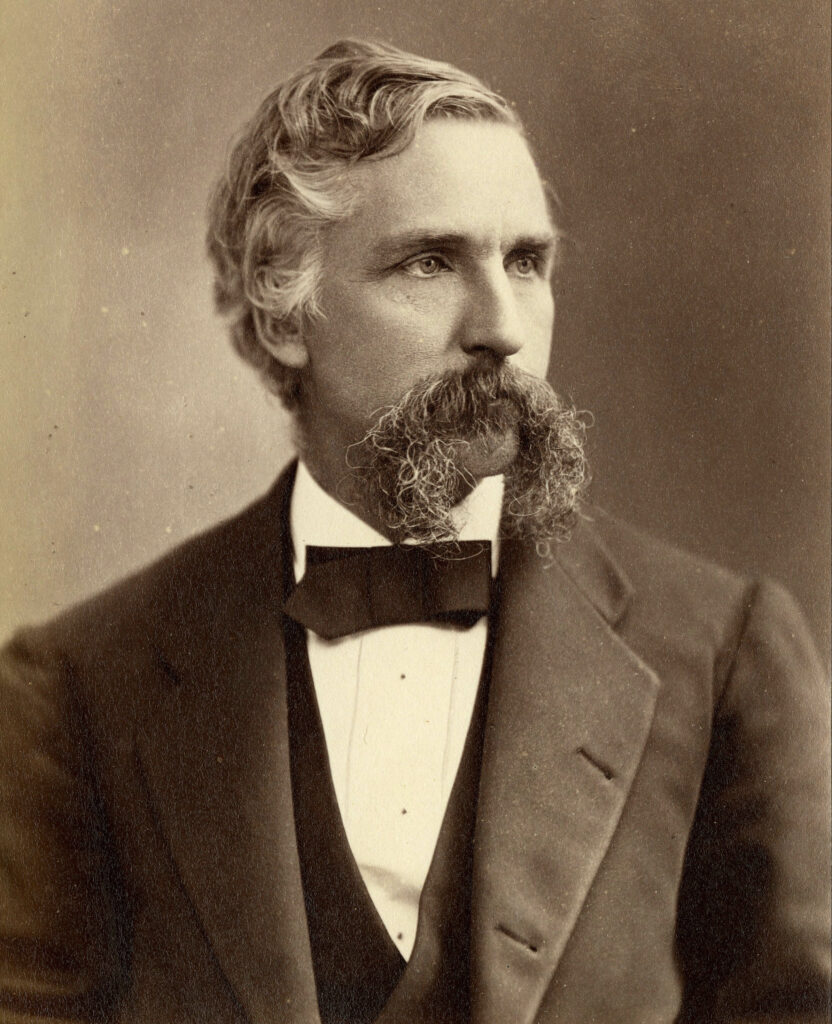

Maine Governor Joshua L. Chamberlain looked at the recommendation for a pardon that his executive council had placed in his hands. As he read the name of the prisoner it concerned, his mind no doubt wandered to a moment from seven years earlier and 500 miles away during the Battle of Gettysburg. That hellish firefight had made his reputation, eventually propelling him to a generalship and later the very gubernatorial seat he now occupied. One image continually returned to Chamberlain’s mind: “Through the mist of the battle could be seen our colors, planted in the ground, and held firmly by our sergeant with musket in his hand. That color-sergeant was Andrew Jackson Tozier, of Plymouth, the man and place well named.” Now that bold and brave flagbearer was imprisoned. What would Governor Chamberlain do?

Born February 11, 1838, Andrew Jackson Tozier was the fifth of seven children of John and Theresa Tozier of Monmouth, Maine. The Toziers’ financial situation was precarious, with just $200 property to their name in 1850. Ten years later, they were designated “paupers.” Older brother Augustus was a sailor, and in 1851 young Andrew followed the same path. Half a century later, Andrew’s wife explained, “He went to sea at the age of thirteen years and followed the life of a sailor continuously [for a decade] accept [sic] short visits to his parents until he enlisted.” Embracing maritime culture, Tozier acquired two tattoos later described as “female on…right arm” and “five pointed star in first interosseous space of right hand.” The second tattoo was likely a nautical star symbolically intended to guide sailors back home.

When the Civil War began, Andrew returned home and enlisted in the 2nd Maine on July 15, 1861, about six weeks after the unit’s formal mustering-in. Not surprising given his worldly experience, height of 6 feet, and tattoos, Tozier stood out, and despite being a later addition to the unit, he was promoted to corporal in early 1862.

June 1862 was a watershed month in Tozier’s life as he suffered the trifecta of disease, battle wound, and capture. The 2nd Maine spent much of June building roads and bridges in the swampy eastern approaches to Richmond. It was backbreaking work with severe consequences. William Jones, a member of the 2nd, remembered Tozier “did become disabled by having contracted Disease of heart, brought on by heavy lifting in building bridges and corduroy roads and exposure to miasma in the Chickahominy swamp.” Remembered William Foss of the 2nd Maine: “Being in the mud and water and hard work he was taken with Heart trouble. He did not go away to the Hospital but staid with the Co. He had fainting spells and would have to be helped to the Doctors tent. He staid with the Co. until the Battle of Gaines’s Mill.”

On June 25, 1862, General Robert E. Lee launched his Virginia offensive known as the Seven Days Campaign. At Gaines Mill, on June 27, he sent 58,000 men against the Union lines. Tozier described the day in his pension file: “After Fighting from 10 oclock till after five in the afternoon on June the 27th 1862 at the Battle of Gaines Mill I was wounded through the left Hand & just after was shot on the inside of my left ankle & was taken prisoner the Ball did not go through but lodged & was taken out by a Southern Doctor the next day.”

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

His mobility limited by the lower leg wound, Tozier was one of 50 men from his unit captured that day. The hand wound was more severe, however—his middle finger requiring amputation at the first joint and those on either side badly damaged. In later years, Tozier’s left arm would measure three-quarters of an inch smaller than his right.

Tozier was confined at Richmond’s Libby Prison on July 13 and then moved to the prison on Belle Isle in the James River. While on Belle Isle, Tozier came across his first cousin, Winfield Norcross of the 7th Maine, who had been wounded at Savage Station on June 29. Despite suffering from chills, fainting spells, and heart problems, Tozier dressed Norcross’ wounds and brought him water. Fortunately, Tozier was exchanged on August 3 and was sent to a hospital in Chester, Pa., to recover, remaining there until late October.

Tozier was promoted to sergeant in late 1862 and then to first sergeant on January 1, 1863. The 2nd Maine had been mustered into state service on May 2, 1861, having signed two-year enlistment contracts as directed by the governor. The Regular Army officer who accepted them for Federal service on May 28, 1861, insisted the men re-sign three-year contracts, though only about 20 percent did so. Later recruits who joined the unit after May 1861, like Andrew Tozier, signed three-year enlistment papers, but many were promised they would be allowed to go home when the 2nd Maine was mustered out in May 1863 at the end of its two years of service.

As spring approached, the men who had signed three-year contracts were anxious about how their situation would play out. The Union Army decided that any “original” members mustered into Federal service on May 28, 1861, regardless of what enlistment period document they had signed, would be allowed to go home. The 120 men who had enlisted after that date, however, would be held to the full three years.

In Andrew Tozier’s case, enlisting six weeks later meant he owed an extra year of service. He and the other men required to stay were sent to the 20th Maine to fulfill their obligation. When the men in that lot were told of their situation on May 23, many mutinied and refused to go peacefully, necessitating their transfer at bayonet point three days later. Forty men continued to protest even after transferring to the 20th Maine, but the rest—Tozier included—fell into line and appeared at drill on May 27. Tozier immediately caught the eye of the 20th’s relatively new colonel, Joshua Chamberlain, who had taken command of the regiment on May 20. Chamberlain was impressed with Tozier’s “behavior + his soldier bearing + personal efficiency…an example of all that was excellent as a soldier.”

The 20th Maine had been engaged at the December 1862 Battle of Fredericksburg, but the regiment was on guard duty in the rear during the Battle of Chancellorsville because of a smallpox outbreak. In early June, a few weeks after its Chancellorsville victory, the Army of Northern Virginia was on the march, hoping to bring the war north of the Potomac River—pursued by the 20th Maine and the Army of the Potomac.

During his northward march to destiny on a rocky hill, Chamberlain was presented with a perfect opportunity to complete the integration of the former 2nd Maine men into their new unit. Elisha Coan of the 20th’s Color Guard later wrote: “A stronger enemy than rebels got the better of Color Sergeant [Charles] Proctor, as brave a soldier as we had in the 20th by the way—the day we marched through Frederick City Md. on our way to Gettysburg, King Alcohol, and thereby the Colors of the 20th were ‘trailed in the dust’ for the first and only time that day.” Proctor’s indiscretion cost him his rank and the position of honor as a color bearer.

Chamberlain selected Tozier as the new national flag bearer, partially in recognition of the man’s record, partially due to his belief that Tozier would perform the duty well, and partially a continuation of his efforts to fully integrate the 2nd Maine men into their new unit. No matter the motivation, it was an inspired decision. And then came Gettysburg.

Glory at Gettysburg

On July 2, the 20th Maine was placed on the extreme left of Colonel Strong Vincent’s 3rd Brigade, which also included the 16th Michigan, 44th New York, and 83rd Pennsylvania. The brigade occupied a position in the saddle between Little and Big Round Top. That meant the 20th was also on the extreme left of the Army of the Potomac. The story is well-known.

During a 90-minute firefight, the Maine regiment repelled six attacks from the numerically superior 15th Alabama. Partway through the fight, Colonel Chamberlain re-fused (bent back) his line to protect the flank, forming his companies into a “V” shape. Holding the colors aloft, Tozier was at the point of that “V”—a position of extreme exposure, so dangerous that one of the color guard assigned to protect him, Melville Day, fell dead with five bullets in him, and another, Charles Reed, would be wounded as well.

Later, Reed recounted that after he was wounded, “Sergt. Tozier said ‘Reed you take the colors and let me shoot’ and we exchanged.” Eventually, the severity of Reed’s wounds dictated that he seek aid, so Tozier took back the flag but continued to load and fire Reed’s musket simultaneously. This scene became one of the iconic images of the fight. Years later, Captain Ellis Spear wrote: “What I most distinctly remember there…was the Color Sergeant Tozier, who had picked up a musket dropped by one of the killed or wounded, and with his left arm about the colors, stood loading and firing, and chewing a bit of cartridge paper.”

The 20th Maine expended all of its cartridges. Ordering the unit to fix bayonets and charge, Chamberlain took his place next to Tozier. The surprise maneuver worked, and the Mainers captured 308 prisoners from five Confederate regiments, securing their position and helping keep the critical height of Little Round Top out of Confederate hands.

Tozier had played a significant role in the unit’s performance. “Immediately after the Battle of Gettysburg,” Chamberlain wrote, “[I] offered him a commission for the special gallantry he showed in that battle. He modestly chose to remain color sergeant.”

Mustering Out

In the spring of 1864, many former 2nd Maine men reenlisted for another three years, earning bounties up to $1,000. Tozier, however, did not. Perhaps his physical condition had deteriorated—his assignment to the army’s ambulance corps in late 1863 suggests that possibility. At some point previously he may also have learned of the death of his younger brother, Ezra, in a Confederate prison camp. Between the debacle with the extra year of service, Ezra’s treatment and death, and his own deteriorating condition, Tozier may have desired to get out of the Army.

Before he could return home, however, Tozier would be wounded yet again. On May 26, 1864, at the North Anna River, Tozier “recd a wound from a ball which struck the left side of head 7 inches behind & above the left eye, & part of the ball escaped & part remained in the wound.” This wound, along with the heart troubles, would become his biggest health concern.

Tozier mustered out on July 15, 1864, receiving $100 in bounty money plus $30.43 from his unused clothing allowance. He likely returned home via train, arriving in Maine in late July. In May 1863, the original members of the 2nd Maine had returned home to a parade in Bangor, and in June 1865, the 20th Maine received the same treatment in Portland. But Tozier returned home without such closure and with little idea of what to do next. He had made his living through physical labor before the war; now he had a crippled hand and ankle, heart trouble, and a bullet fragment lodged in his skull.

There was some promise. On February 28, 1865, Andrew married 18-year-old Lizzie Bolden, his third cousin. Sometime during that winter, Tozier had the lead fragment removed from his head, but the surgery brought on occasional headaches. On May 24, 1865, he applied for a pension, claiming total disability resulting from his heart troubles, crippled hand and ankle, and head wound. The fact that he could not support himself in his current condition surely was a blow.

Lizzie became pregnant sometime around July 4. The couple might have known this by August 18 when the Pension Bureau declared that the thrice-wounded Tozier was “very slightly” disabled and deserved only one-third of a pension amounting to $2.67 a month. This appears to have been the final straw in pushing him toward crime.

Crime and Punishment

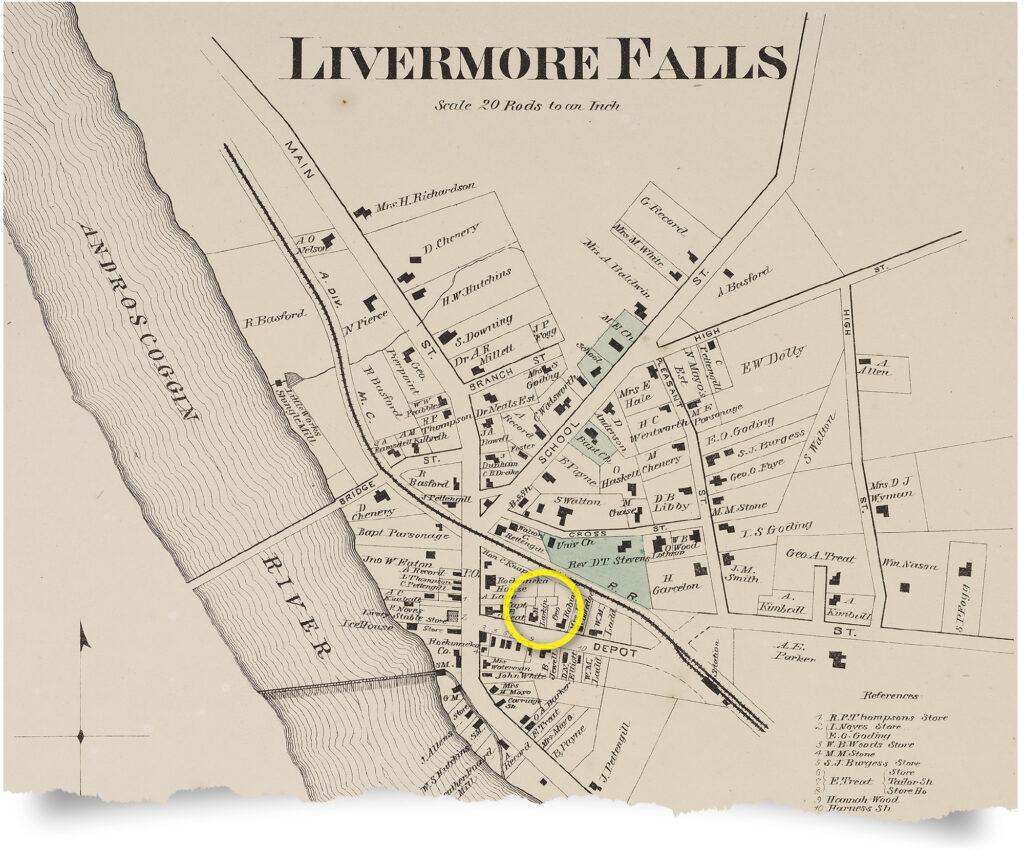

The Portland Daily Press of September 1 reported, “HEAVY ROBBERY OF CLOTHING. – The store of Mr. Larkin, at Livermore Falls, was broken into Tuesday night, and clothing of the value of $2000 was stolen. A reward of $200 is offered for the recovery of it.” On the night of August 29, two men broke into Michael Larkin’s store in Livermore Falls and used a stolen cart to carry away 154 coats valued at $1,920. In mid-September, a man named Jerry Riggs was accused of the crime, but the grand jury chose not to bring a bill of indictment for lack of evidence, which proved correct. Four years later, it was determined the robbery was committed by Andrew Tozier and his half-brother, Lewis Cushman.

Immediately after the robbery, Tozier must have realized he would have difficulty turning the coats into cash without arousing suspicion, so he hid them at his brother-in-law’s in East Dixmont. Ironically, on December 15, 1865, Joshua Chamberlain gave his first public address on the fight on Little Round Top. Reprinted five days later in the Eastern Argus, Chamberlain’s address brought the name of Andrew Tozier before readers across the state just as the man was desperate to keep a low profile.

In January 1866, Tozier underwent another pension examination, and the examiner noted in the application, “Gen. Chamberlain recommends him highly.” The Toziers welcomed a baby boy named Andrew Jr. on April 4, 1866, and three months later saw a slight pension increase that brought the monthly amount to $4. Tozier struggled during this period, for his doctor observed, “There is evidently considerable cerebral disability,” while another noted that during a recent examination, Tozier was “so bewildered” that he had to sit down abruptly. By February 1867, the pension was increased to $6 a month, a tiny sum to support a family of three.

Desperate, Tozier again turned to crime. With Cushman and another man named Charles Shorey, he stole six oxen valued at $850 on October 9, 1868. The men drove the cattle 100 miles to be slaughtered in Augusta, but Tozier stopped short of the capital and while the other two men were seeing to the animals’ disposition, they were caught and arrested. The ensuing trial took place in Kennebec County. Both Shorey and Cushman pled guilty and implicated Tozier in the crime. Since Tozier did not enter Kennebec County while engaged in the crime, however, he was dismissed for lack of jurisdiction. This was but a small victory, as he was immediately arrested by authorities from Washington County, the locale from which the cattle had been purloined.

The April 1869 trial in Washington County drew wide attention. Tozier pled not guilty, and accomplice Shorey served as the principal witness for the prosecution—an act for which the State paid him $33.90 for his time and distance traveled. A dozen other witnesses who had seen the three men with the cattle verified Shorey’s testimony. Tozier’s attorney, George Brown, hoped to create reasonable doubt through misidentification, so he placed Andrew’s older brother and near-doppelganger George in the courtroom’s front row, closer to the witness stand than Andrew, and asked one of the younger witnesses to identify the cattle thief.

The trick backfired when the youngster passed over George and pointed to Andrew. Frustrated and perhaps embarrassed, Brown spewed that he “did not care if Tozier was found guilty—Gov. Chamberlain would pardon him.” Indeed, most of Brown’s “defense” of Tozier was a recounting of Andrew’s war record rather than a rebuttal to the evidence of a crime.

More on the 20th Maine

Brown had calculated well, for despite clear evidence the jury found Tozier not guilty. Three of the 12 jurors had served in the Civil War, and Foreman Luther Hanscom had a son who served in the 1st Maine Cavalry. Tozier, though, had mere seconds to celebrate his victory before he was arrested by officials from Androscoggin County and charged with robbing Larkin’s store four years earlier. During his imprisonment and guilty plea, Lewis Cushman admitted to the theft at Larkin’s and identified Tozier as his partner. On May 14, 1869, Tozier was arraigned in Livermore Falls and released on a $1,000 bond to await trial at the next session in September.

The Maine Statutes determined that larceny—a crime committed without the use of violence and without danger to people—exceeding $100 would be punished by at least one but no more than five years in the state prison. Tozier’s sentence was “punishment by confinement to hard labor,” which was both the standard of the day and a ridiculous irony given that Tozier’s inability to labor led to his crime in the first place.

Tozier was incarcerated at the state prison on February 17, 1870, one of 53 men sent to that facility in 1870. Lewis Cushman was already serving a four-year sentence—likely reduced due to his testimony against Tozier. While incarcerated, Tozier worked manufacturing carriages, boots, or shoes, with the sale of those items making the prison economically self-sustaining.

Tozier had served just three months and six days when the executive council recommended the governor pardon his former color sergeant. Throughout his four years as governor, Chamberlain pardoned 59 men, a rate in line with his predecessor and successor. In 1870, Chamberlain pardoned 11 inmates, and Andrew Jackson Tozier would be one of those men.

A Fresh Start

Chamberlain did far more than pardon Andrew Tozier. Perhaps worried that a pardon offered only a temporary reprieve, he offered Tozier a job and a place to live. By the time the census taker appeared on August 1, 1870, the Toziers were living in Chamberlain’s Brunswick house, with both Andrew and Lizzie identified as “domestic servants.” Pension forms that Tozier filed carried a “Brunswick” heading until 1875, the period of Tozier’s rehabilitation.

By 1875, the Toziers were stable and ready to strike out on their own, and Andrew purchased a 10-acre farm on Great Chebeague Island in Casco Bay, where the family would spend the next 15 years. In 1876, Maine’s Civil War veterans held a grand reunion in Portland with 1,500 men in attendance. There, the 20th Maine formed a regimental association. The association’s minutes noted, “The ‘boys’ spent a short time recalling some of the incidents of the war, after which an invitation was accepted for an hour’s sail in Gen. Chamberlain’s yacht, which was found in charge of Color Sergeant Andrew J. Tozier.”

Tozier continued to fight for an increase to a full pension, and Chamberlain was a constant supporter of his efforts, writing in 1878 and 1879 of both his wartime heroism and his postwar struggles: “I know that he has since suffered much from these wounds, especially from that in his head, so much so as to be entirely incapacitated from labor at frequent intervals.” The examining surgeon concurred, reporting a pulse of 100 and noting, “He is evidently suffering from serious nervous disturbance. The countenance is anxious and expressive of suffering. The eyes are suffused and his memory somewhat defective.” Finally, in late 1878, his rate was increased to $8, the maximum then allowed.

Happiness came to the Tozier family on October 8, 1879, with the birth of a daughter. They named her Grace after Chamberlain’s daughter, further testament to Tozier’s gratitude toward his old commander. The close relationship between the old war heroes is perhaps best illustrated in a letter from Tozier to Chamberlain in late 1880 asking his former colonel to lecture on the Battle of Gettysburg at a church benefit. After the request, Tozier moved on to personal matters:

My family are all well + I am rite smart. I go a winter fishing I have ben out two trips hoping you are all well I remain your Humble Servt

A.J. Tozier

P.S. did you get the yacht up all right?

“This Soldier Stood Alone”

In 1890, the Toziers moved to Litchfield, where they would be near many family members. Andrew worked at the nearby Plimpton’s Hoe and Fork Factory at light work when his health allowed from 1890 until 1902.

The highlight of Tozier’s postwar life came in 1898 when he received the Congressional Medal of Honor for his actions at Gettysburg. Again, his former commander was behind the recognition. In 1898, Chamberlain served on the commission that published Maine at Gettysburg. Chamberlain wrote the 20th Maine’s entry and said of Tozier: “At one moment, it looked as if the colors of the Twentieth Maine must be lost. Buried from sight in smoke, when the black cloud lifted for a moment the colors were seen almost alone. All the Color-Guard and the flanks of the companies on its right and left were cut away; but the Color-Sergeant, Andrew J. Tozier, was standing his ground, the staff planted on the earth, and supported within his left arm, while he had picked up a musket and was defending his colors with bullet, bayonet, and butt, alone!”

Believing Tozier’s actions were worthy of higher recognition, Chamberlain recommended him for the Medal of Honor in 1898. When the medal was issued that August, its citation forever enshrined those moments on Little Round Top: “At the crisis of the engagement this soldier, a color bearer, stood alone in an advanced position, the regiment having been borne back, and defended his colors with musket and ammunition picked up at his feet.”

Over the ensuing decade, Tozier’s health declined, and he was often housebound and even bedridden for months at a time. After his house burned down in 1899, Andrew Jr. moved next door to his father, and soon there were three grandsons for Andrew and Lizzie to admire. In Andrew’s later years, Dr. Winfield Norcross, the cousin whom he had nursed through their captivity in Richmond, offered him all the care he could. Finally, the heart trouble Tozier contracted in 1862 caught up with him, and he passed away on March 28, 1910.

Andrew Tozier had grown up in challenging circumstances before leaving for the sea at age 13. Shot up and worn down with sickness during the Civil War, he nevertheless answered the call when his new regimental commander asked him to take on the unit’s deadliest position, color bearer. Tozier came through for Chamberlain, both with his quiet example helping to quell the mutiny among the 2nd Maine men and on Little Round Top where he, the old sailor, set an anchor on the rocks at the center of the 20th Maine’s line and helped break wave after wave of Rebel soldiers that rolled toward him. In the postwar years, it was Chamberlain who came through for Tozier, looking past the crimes he had committed to see a warrior in need and then ensuring that his old comrade was on firm footing before he cast off on his own once again. The two Medal of Honor recipients lived divergent lives, but yet were inextricably linked.

Jared Peatman’s Four Score Consulting uses history to examine current leadership and performance challenges. His first book was The Long Shadow of Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address, and he is nearing completion of a book on the 20th Maine.