In 1902, seven years before his death at age 66, Union veteran Ezra H. Ripple penned a memoir of his prison life for his “wife and children with no expectation of using it beyond the walls of our home,” as he stated in the introduction. Fortunately, however, that memoir found its way to publication in 1996 as Dancing Along the Deadline: The Andersonville Memoir of a Prisoner of the Confederacy, edited by Mark A. Snell. In the memoir, Ripple chronicled his life as a soldier in the 52nd Pennsylvania Infantry. His regiment was involved in the siege to capture Charleston, S.C., and on July 3, 1864, the 52nd participated in an attack on Fort Johnson, an earthwork stronghold on the northern edge of James Island that guarded the approaches to the Ashley River and Charleston Harbor. Although the Keystone troops broke into the fort, a Confederate counterattack drove them out and captured 135 men of the 52nd, including Private Ripple. He was sent to the prison at Andersonville, Ga., for two months, then to the prison at Florence, S.C., in October 1864 for seven months. Ripple survived, and went on to a successful postwar career in business and politics, moving to Scranton, Pa., and eventually becoming mayor of that city in 1886. But he never left the war behind. Ripple commissioned noted Civil War artist James E. Taylor to create sketches of his prison life, and later had those illustrations transferred to glass plates and colorized as magic lantern plates, or slides, so he could give talks at G.A.R. meetings and public gatherings about his months of grueling incarceration. The following examples of the original slides, held at Scranton’s Lackawanna Historical Society, provide a flavor of Ezra Ripple’s harsh time in Confederate prisons.

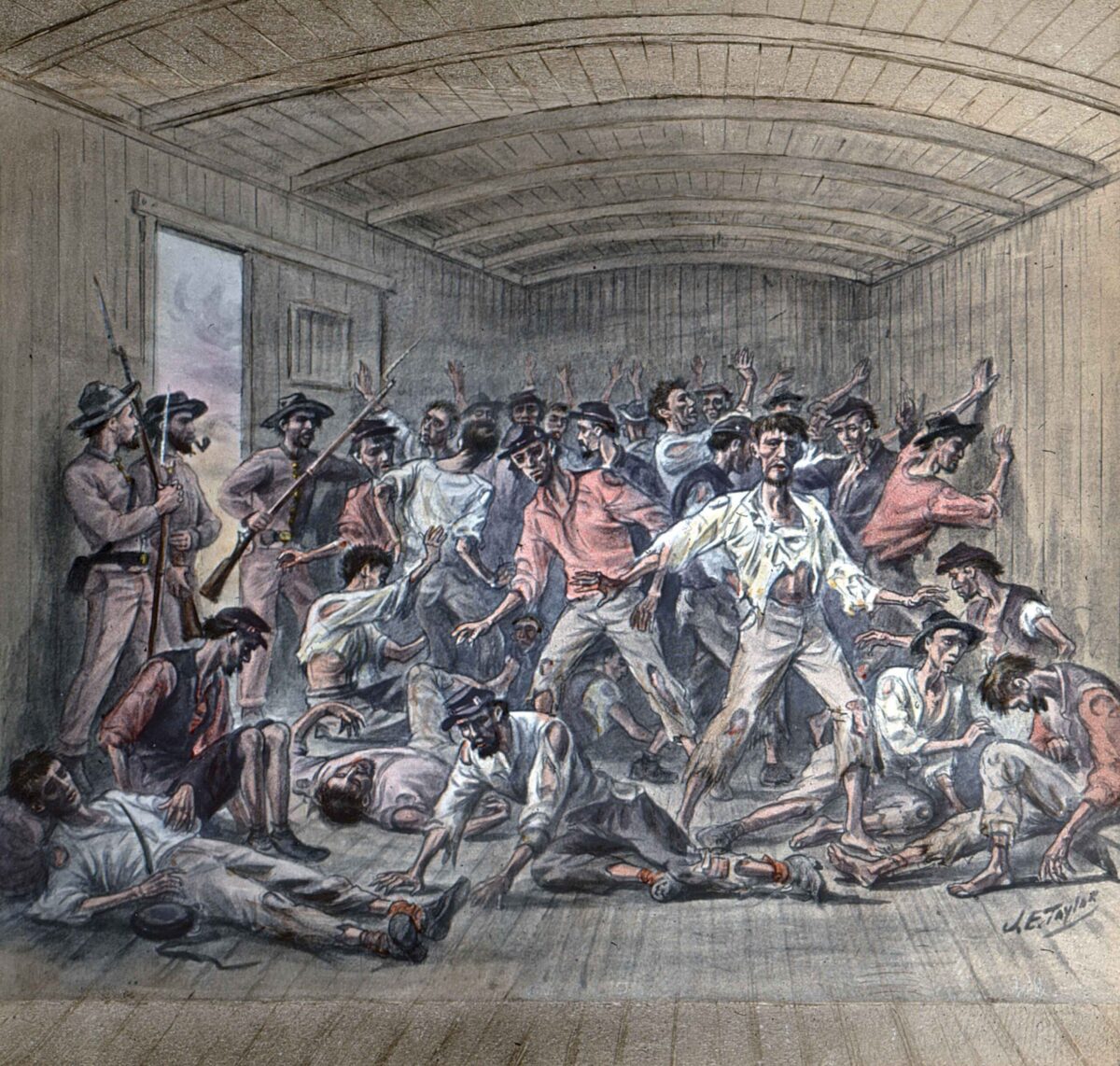

Shot At The Deadline

When Ripple arrived at Andersonville in July 1864, he estimated there were 25,000 men in the prison formally known as Camp Sumter. It reminded him of an “immense anthill teeming with life.” As the new prisoners filed into the log stockade enclosing about 25 acres, old hands warned them of the “deadline,” a simple rail fence that prisoners could not touch or pass without penalty of death. Ripple saw many men, like the one pictured above reaching for an item he had dropped over the railing, breathe their last when a guard shot them for crossing the line.

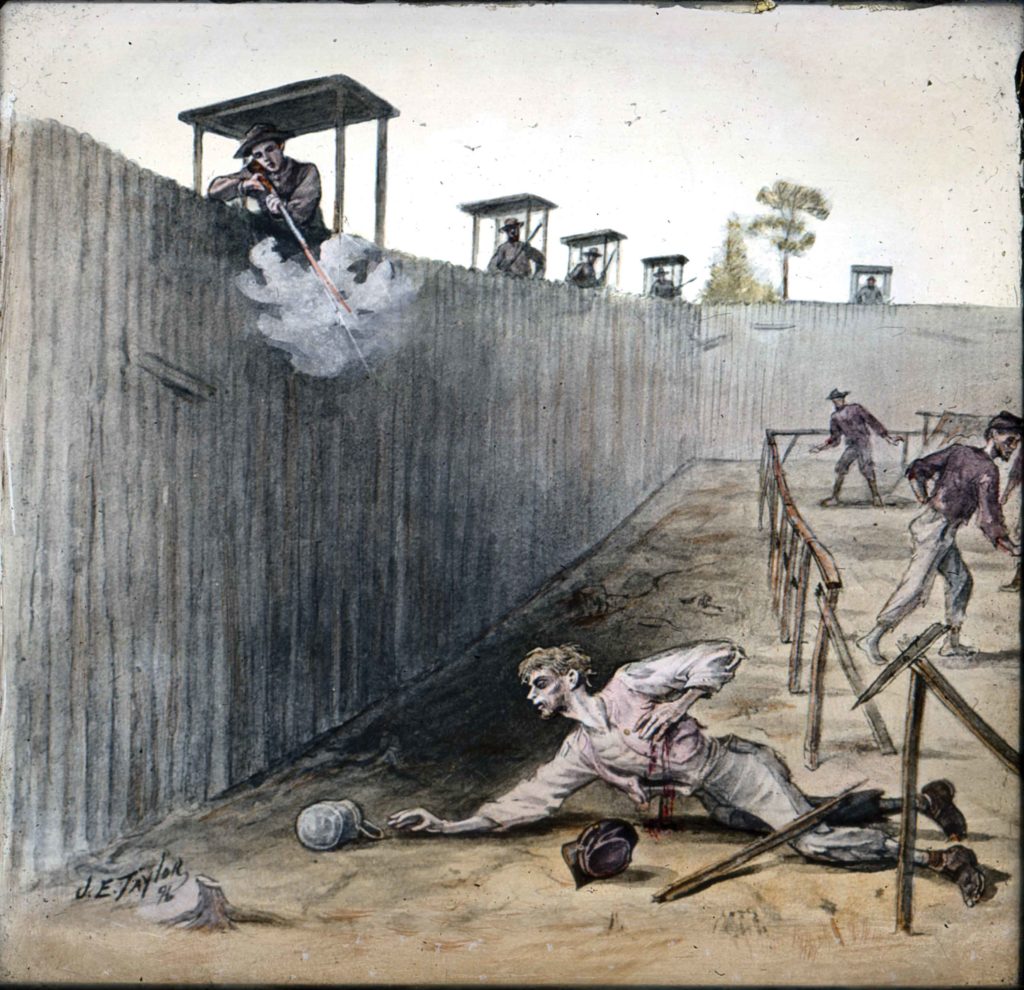

Nine Under Two Gum Tents

No shelters were built for the prisoners at Andersonville, who relied on weather-beaten tents and gum blankets to shield them from the Georgia sun. “Not a particle of vegetation could be seen, the surface trampled as hard as the floor of a brick yard, and resembling a half-burned brick in color,” Ripple recalled of the heat-scorched prison pen. To try to stay out of the sun and avoid the evening dew, Ripple and eight other men lay with their heads under two gum blankets lashed together. The ersatz shelter was too small to fully accommodate the prisoners, and he said their legs remained exposed to the weather and “sticking outside like the spokes of a wheel.”

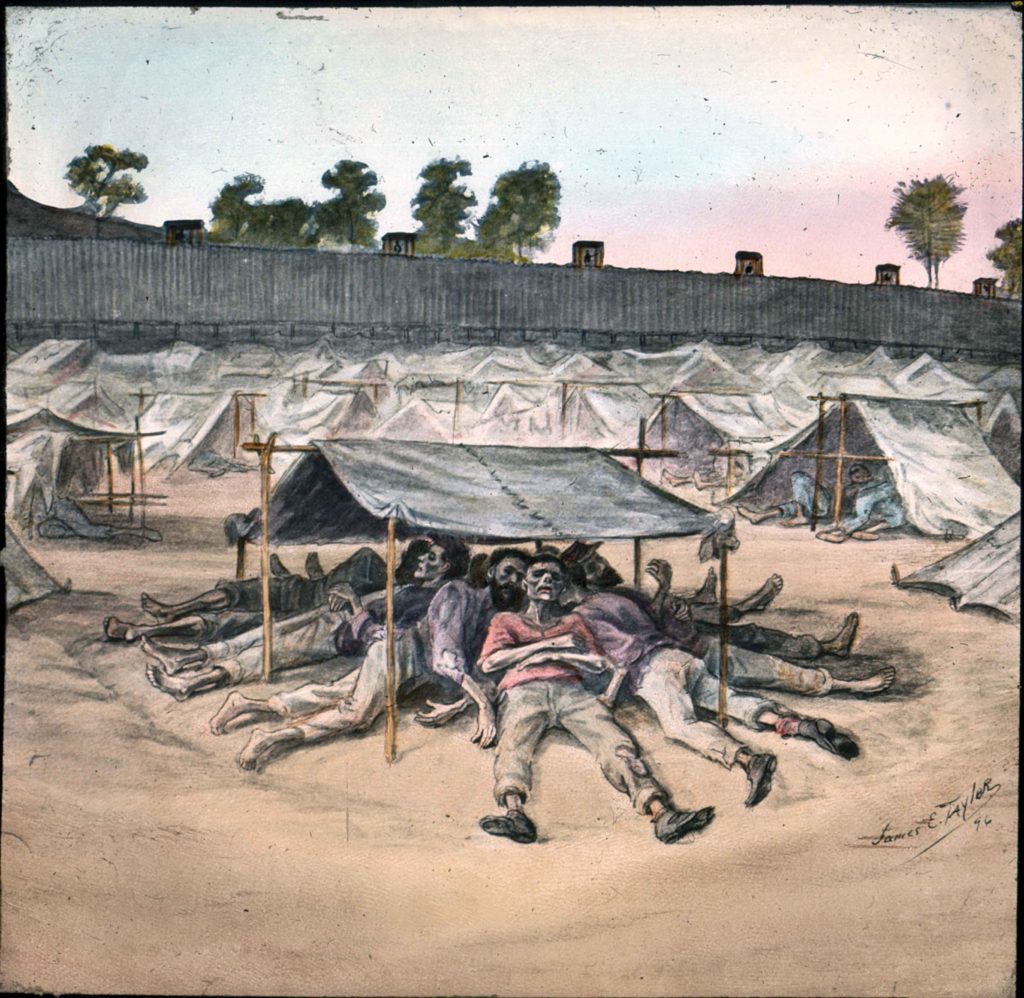

Punishing A Thief

The prisoners developed ad hoc criminal justice systems to bring order to chaos in both Andersonville and Florence. In this sketch, after fellow captives have shaved half a prisoner’s head to identify him as a thief, they drive him out of their mess group to seek shelter elsewhere. Ripple claimed such punishment was “novel and very effectual….”

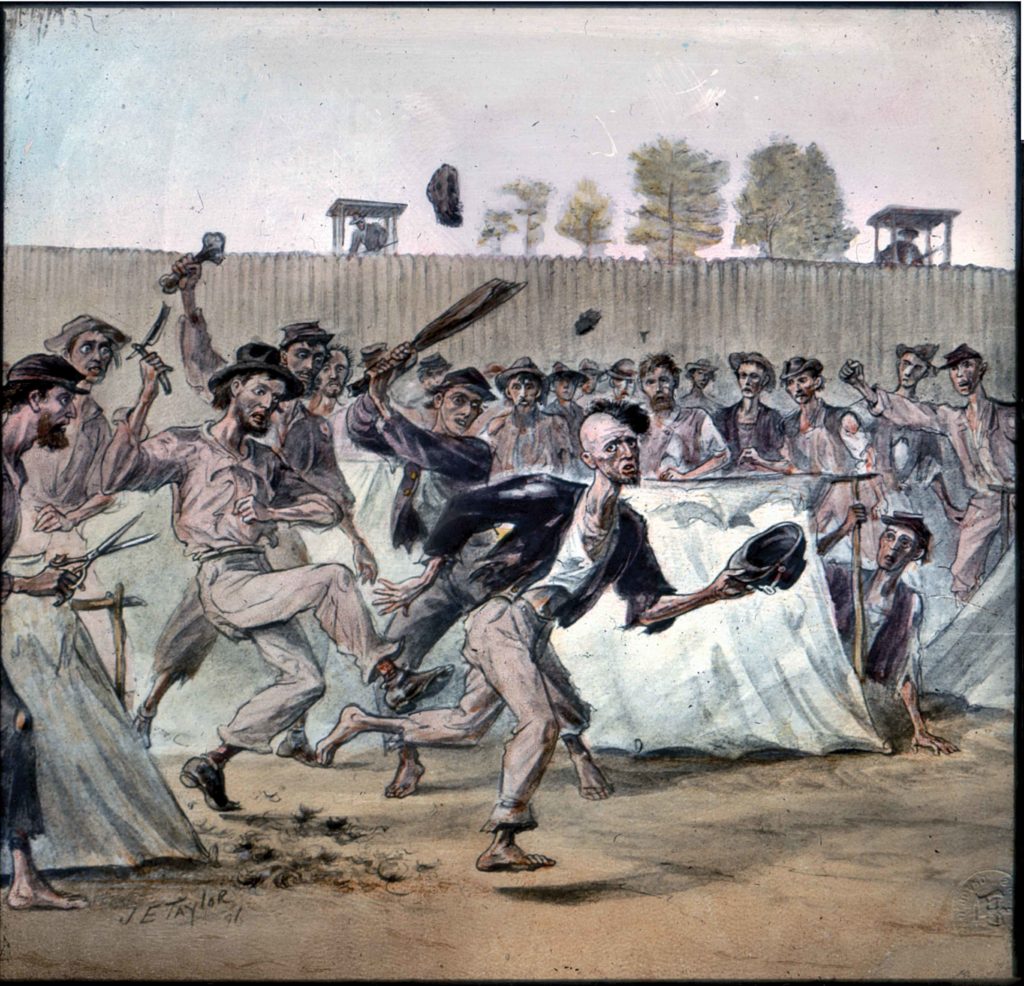

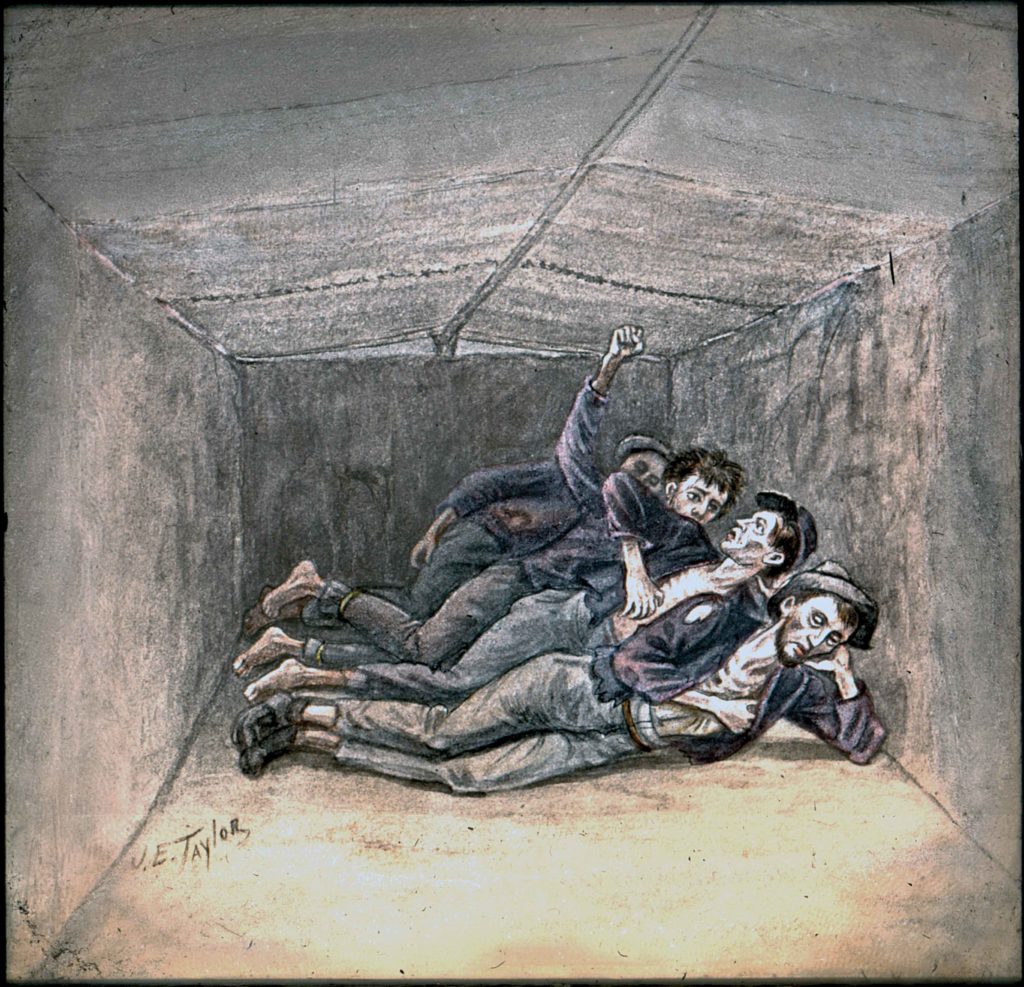

Four Of Us Sleeping In The Hole

When Ripple and his comrades entered the new Florence prison in October 1864, they had to prepare for winter. Desperate times call for desperate measures, and he and three comrades dug a three-feet-deep hole to sleep in and roofed it with gum blankets. In the cramped pit, “our shoulders and hip bones made holes in the ground,” remembered Ripple.

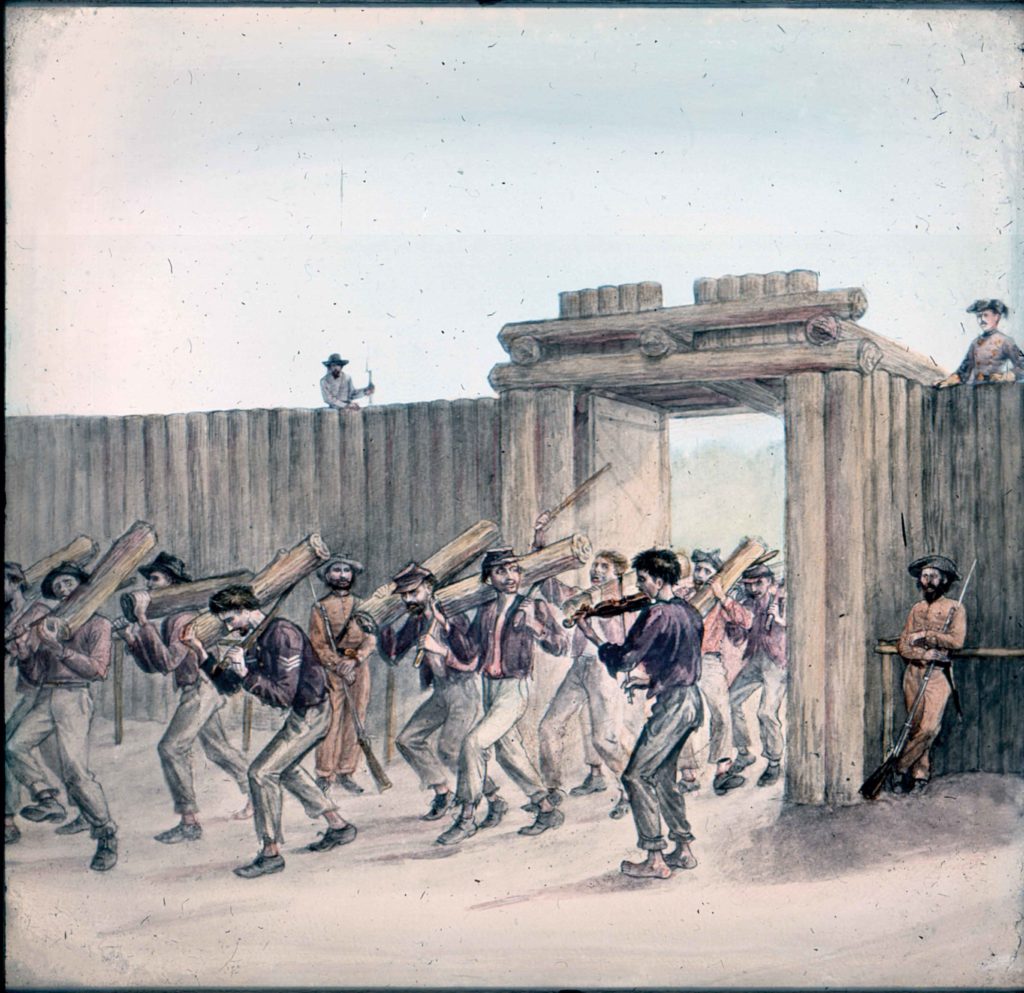

Fiddling For The Wood Squad

Ripple had shown an affinity for the fiddle from an early age, and that skill helped save his life in prison. There were several fiddles in the Florence stockade that he would play in exchange for extra food. On one occasion, camp commander Lt. Col. John Iverson had Ripple play to energize prisoners bringing firewood into camp.

Gangrene Cases

“Short of death, the thing we most dreaded was gangrene,” shuddered Ripple. In this ghastly watercolor, a prisoner cuts off the gangrenous feet of a fellow inmate in a desperate attempt to stop the rot and save his life. Ripple could not shake the memory of how the “bones would protrude white and glistening” after such crude prison surgeries.

Fight With The Dogs

Ripple formed an inmate orchestra while he was at Florence, and the musicians were often sent to play at local plantations. After one such outing in February 1865, the fiddler and several comrades decided to escape. Weak and weary, they hadn’t gone far when Ripple heard the “distant bay of the hounds” of the prison dog pack. He fled into a swamp, but they were soon on him, biting and tearing his flesh, and he was only saved by pursuing Confederate cavalrymen. The troopers led a torn and bleeding Ripple staggering back to the prison. Fortunately, as he was a camp favorite, his guards helped nurse him back to health, but his days of being allowed outside of the prison were over. The trauma of the dog attack never left Ripple. “…Many, many times after I got well did I have the horror of it all in my dreams,” he admitted.

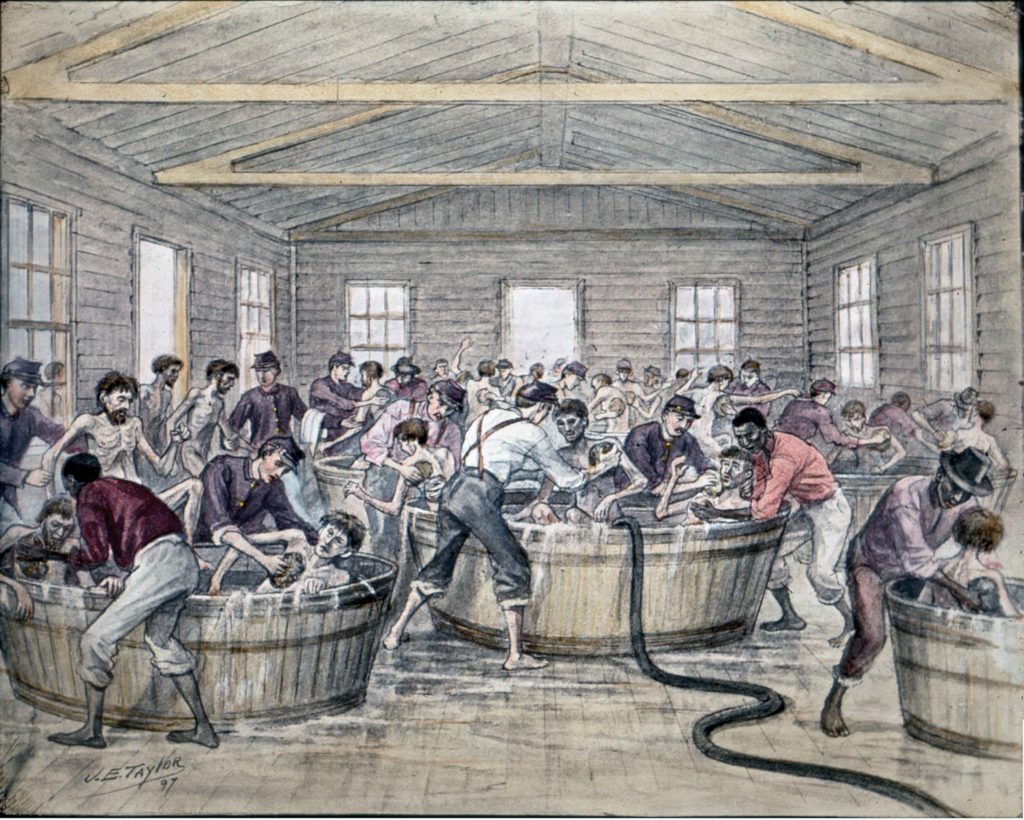

Washing Up

On March 1, 1865, Ripple’s prison term ended when the Florence inmates were paroled. The exhausted and emaciated prisoners were transported to Wilmington, N.C., where Ripple shed “tears of joy” at the sight of the U.S. flag. One more rolling, pitching trip awaited the soldiers, but this time instead of a train it was a “slow old tub” of a ship that took five days to reach Camp Parole at Annapolis, Md. After arriving, Ripple and his comrades were stripped of their clothing and, as seen above, placed in large tubs that held 12 men. “It was the nicest bath I ever had in my life,” said a relieved Ripple. The former prisoner mustered out in June 1865, and he recalled that once he got home, “gentle nursing” and “kind care” helped him heal and live a fruitful postwar life.

Traveling Storytellers

Magic lanterns brought vivid images to life

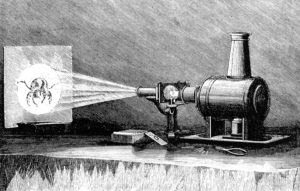

In 1659, when Dutch scientist Christian Huygens sketched a series of ten images of a skeleton taking off its skull, with the notation “for representations by means of convex glasses with the lamp,” he could not have envisioned Ezra Hoyt Ripple’s cathartic use of his image projection system to share with others the horrors of life inside Confederate prisons. In fact, Huygens later came to regret the invention, which was often used in its early days to scare audiences by mysteriously making images of devils and angels appear on the walls, earning it the name “magic lantern.”

The lantern projector used a concave mirror behind a light source to direct light through a small sheet of glass on which the image was painted or printed, called “lantern slides.” In 1848, the German-born brothers Ernst Wilhelm and Friedrich Langenheim invented the first photographic lantern slides, called “Hyalotypes.” They were patented in 1850 and the brothers began to sell them commercially. American versions of the slides measured 3.25” x 4” and consisted of two sheets of glass. One sheet carried the image and the other sheet covered it. They were bound together all around the edges by black paper tape. The slides were produced by black and white photography, but were often then colored by hand.

Americans also made slides from drawings by creating a master drawing, photographing it, and then printing slides. It was this technique, rarely used elsewhere in the world, that Ripple used to create his absorbing collection of lantern slides depicting scenes of life at Andersonville and Florence prisons.

The earliest versions of magic lanterns used the only available light sources outside of the sun, including candles and oil lamps, which could produce only dimly projected images. As new light sources were invented over the years, the quality of the projected image improved as well. The 19th century use of limelight and the arc lamp made it possible and practical to project bright, clear images in front of large audiences.

Magic lantern projectors in the 17th century were used typically for entertainment purposes, but these advancements in the quality and safety of light sources made them attractive tools for traveling salesmen and educators in the 18th and 19th centuries. The slides could be used to illustrate products for purchase or lectures on travel, science, and religion—or, in Ezra Hoyt Ripple’s case, to illuminate the common soldier experience during the Civil War, including the conflict’s sobering atrocities. –Melissa A. Winn