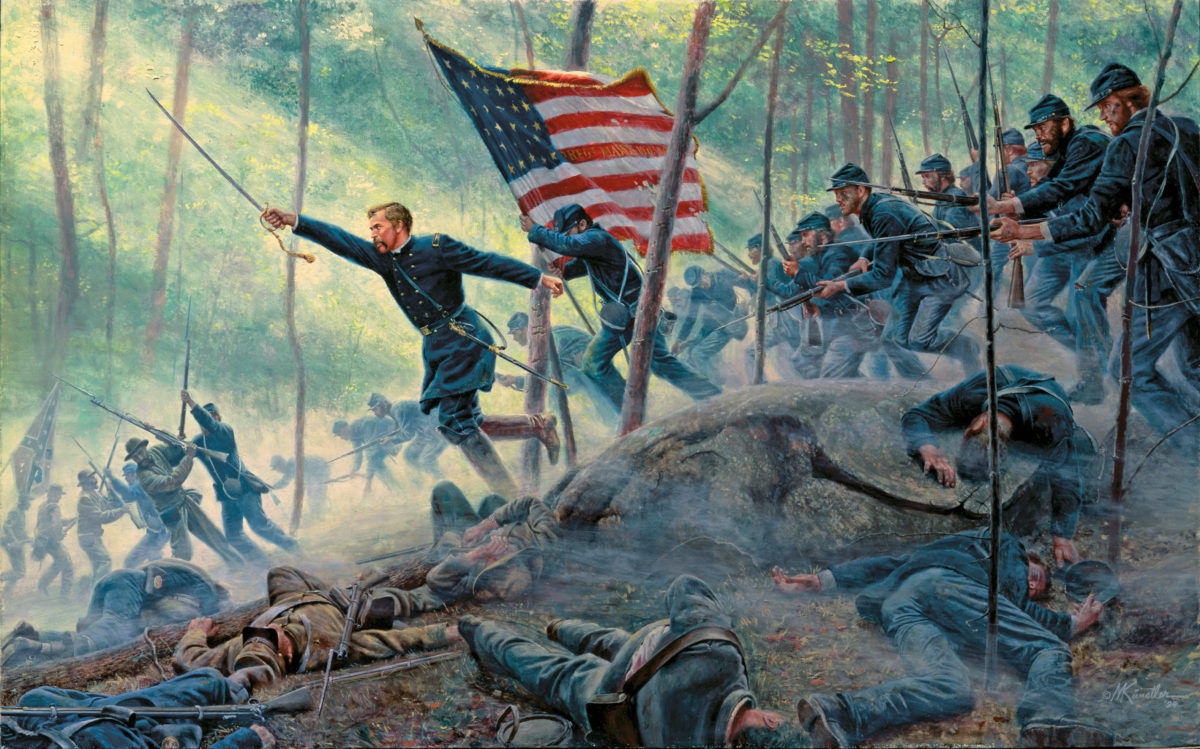

It is a story made famous by the likes of Ken Burns, Jeff Daniels, and Ted Turner. A small, inexperienced infantry regiment in the Civil War finds itself defending the key to the outcome of the largest battle in the history of North America. Attacked by a force superior in both numbers and experience, the little band of Mainers holds off assault after assault and, with a surprise bayonet charge, saves the Union army, and perhaps the Union itself, from destruction.

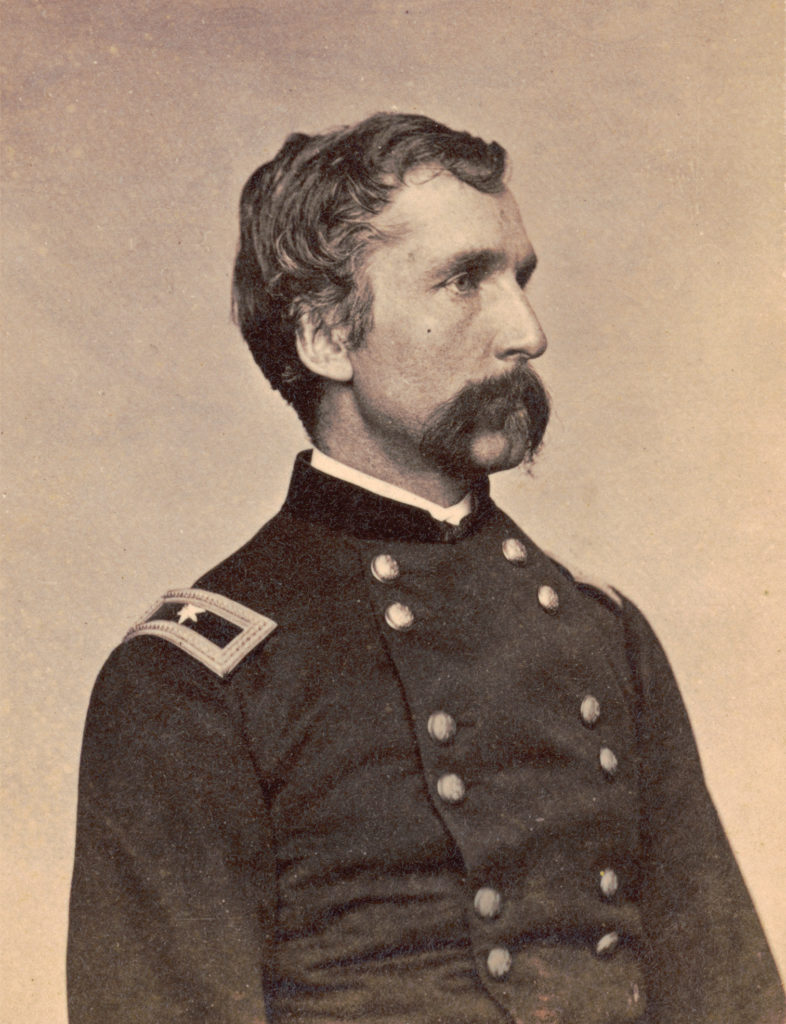

Particularly in the past few decades, few stories from the Civil War have received as much attention as that of Colonel Joshua L. Chamberlain and his 20th Maine Infantry at Gettysburg. The subject of novels, documentaries, artwork, and a feature film, the efforts of this one regiment to save the Union army in the epic three-day battle have become legendary.

Placed on the far left of the Union position on the battle’s decisive second day, the unit became the target of a massive Confederate assault on the end of the Yankee line resting on a small hill that later became known as “Little Round Top.” After an hour and a half of intense, sometimes hand-to-hand fighting, and with a third of his men down and others running out of ammunition, Chamberlain and his men went on the offensive, carrying out an unexpected bayonet charge that swept their Alabama attackers from the field and secured the Union left.

More than a century ago, Colonel William C. Oates, commander of the 15th Alabama soldiers who attacked the 20th Maine, wrote of his Yankee counterparts: “[Chamberlain’s] skill and persistency and the great bravery of his men saved Little Round Top and the Army of the Potomac from defeat.”

Decades after Oates, Southern historical writer Shelby Foote said of the Mainers and Alabamians who fought on the small but tactically crucial hill: “[T]he men of these two outfits fought as if the outcome of the battle, and with it the war, depended on their valor: as indeed perhaps it did, since whoever had possession of this craggy height on the Union left would dominate the whole fishhook position.”

Filmmaker Ken Burns, whose 1991 PBS documentary made Foote famous and forever changed the way people see the Civil War, said of Chamberlain: “He executed an obscure textbook maneuver that only an academic would remember at the battle of Little Round Top that saved the day, saved the Union Army perhaps and maybe saved the Union.”

But there was no textbook, and the 20th Maine performed no obscure maneuver. That there is no evidence to support facts such as these has seemingly had no effect on the misperceptions of millions who encounter the story and the great importance heaped upon it by modern chroniclers.

One of the first things that happens to soldiers who report to Officer Candidate School in the U.S. Army is they are handed a copy of Field Manual 22-100, the guidebook that will inform their training on the road to becoming officers. The first lesson they encounter in this book, beginning on page 8, is the story of the 20th Maine at Gettysburg. This example of military leadership concludes by saying, “For a few moments, the fate of an Army [sic] and a nation rested on the shoulders of 358 farmers, woodsmen, and fishermen from Maine.”

When Robert F. Kennedy Jr. decided in 2007 to create a series of children’s books called “Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s American Heroes,” he chose as the subject of its first volume Joshua Chamberlain and the American Civil War. In it, he describes how Chamberlain and his men “saved our country from destruction” on Little Round Top at Gettysburg.

In his 2014 autobiography, U.S. Army combat veteran and former Congressman Allen West called Chamberlain, “[o]ne of my favorite leaders in American history.” He then described the Maine warrior’s most famous action by writing, “using a maneuver called a ‘swinging gate,’ (he) created a frontal assault and flanking attack simultaneously, leading the charge that saved the day at Little Round Top. With his actions, Chamberlain saved the Union Army of the Potomac.”

All the same, in widespread popular culture, few if any have taken an in-depth look at all the circumstances from that encounter and determined whether the role of the 20th Maine lives up to the heroic modern assessment applied to it in literature, film, and in other ways. By peering behind the legend and the modern machinery of myth-making, does the story as told and believed so widely today compare to what our society has built it up to be?

The main question to be answered is: Was there ever a possibility the Rebels could have seized Little Round Top, placed artillery there, and used it to “shell the U.S. army into submission”? If that answer is no, then a discussion about whether anyone saved the Union Army or the Union itself on Little Round Top is moot. To answer this key question, let us consider the best possible scenario for the Confederate troops and the worst-case scenario for their Union counterparts to see if the idea is feasible.

Unfolding circumstances denied the Confederates the benefit of a reserve force that could have exploited any gains made by those who attacked the hill initially. The movement of the Union left flank southward just prior to when the Alabamians stepped off on their assault, meant that the far right of the attacking force had to move and stretch to the right of their original angle of attack. This was compounded when Yankee sharpshooters began harassing the Alabamians from the base of Round Top on their right, requiring a further shift in this direction to clear their flank of enemy fire. As this unfolded, it became clear that the line of battle was stretched too thin and the 44th and 48th Alabama regiments that would otherwise have provided support as reserve troops, stepped up to the front line and instead moved away from the far right of the assault. These two regiments fought in Devil’s Den with far fewer casualties than other units in their brigade.

An analysis of strengths and casualties shows that about the time of the now famous charge of the 20th Maine, Colonel Oates’ 15th Alabama had about 330 men still engaged in the fight. In a best-case, although unlikely, scenario, these might have been supplemented by others in the brigade. If, for example, 90 men of the 47th Alabama, which had left the fighting in its initial minutes after suffering heavy losses, had somehow rallied and returned to the fight, and if 260 men remaining on duty in the adjacent 4th Alabama had joined the assault, the renewed Confederate attack might have numbered 680 men.

Assuming the remnants of the three regiments of Law’s Alabama Brigade close enough to exploit a collapse of the 20th Maine’s line were able to rally and focus their efforts toward the top of the hill, and also assuming that the remaining regiments of Union Colonel Strong Vincent’s 3rd Brigade were at their weakest point of the battle—neither of which is a safe assumption—then roughly 680 Alabamians, fighting uphill, would have had to dislodge and defeat nearly 17,000 Yankee infantrymen.

As they joined forces and renewed the assault on Little Round Top, climbing upward, the Alabamians would first have faced the 800 men of Vincent’s brigade still on duty. Had they somehow swept these soldiers aside, they would have been met by at least 1,285 soldiers of Brig. Gen. Stephen H. Weed’s brigade, including the remnants of the 140th New York that had just driven the 4th and 5th Texas from the hill.

If the remaining 680 Alabamians somehow succeeded in seizing the summit of Little Round Top, they would have then faced the full force of Union soldiers in the vicinity in what would surely have been an immediate and forceful effort to retake the hill. In all, there were more than 16,900 Union soldiers within just one-half mile, assuming these nearby units were then at their lowest strength levels of the entire battle. Of these, about 10,000 had yet to be engaged in any fighting at that point.

In the unlikely scenario in which fewer than 680 Alabamians make an attack on Little Round Top, and in the worst case for their enemy they are met by nearly 17,000 Union troops, the probability that the Confederates could have taken and held Little Round Top is undoubtedly zero.

For argument’s sake, let us say these exhausted, outmanned Alabamians somehow took and held the hill. Then they could have—or so legend has it—brought artillery to the summit and “bombarded the Union army into submission.” As one Pennsylvania professor once wrote, “Confederate artillery emplaced upon this height could enfilade the Union line and render it untenable.” But is this statement supported by the facts?

This legend is betrayed by two critical elements: Getting guns to the hill and finding ground on which to place them for action.

First, the summit of Little Round Top is a very poor artillery platform, particularly when aiming northward toward the Union line of battle. The effective range of a Confederate rifled cannon is around 1,820 yards, or just more than a mile. Any artillery piece fired from the summit would have been able to reach no more than a third of the Federal line within sight of the hill, which in turn was little more than half of the overall Union force.

Then there is the uncooperative shape of the summit. Little Round Top was not so named because of the roundness of its top. It became known by that name years after the battle simply because it was adjacent to and smaller than its neighbor, Round Top. Given the decidedly non-round topography of the hill, it is unlikely that any more than four pieces of artillery could be brought to bear in the direction of the Union line.

Again, this could only be accomplished if the 17,000 otherwise unoccupied Union soldiers in the near vicinity decided not to hamper, much less destroy, any Confederate artillery that became engaged from the summit.

Secondly, there is an enormous problem of command and control. For even a single piece of Southern artillery to begin firing from the summit, some Confederate officer with the authority to do so, would have to order it there. The nearest available guns were among the batteries of Cabell’s Artillery Battalion roughly a mile to the west. These, however, were under the command of Maj. Gen. Lafayette McLaws, whose division had borne the brunt of the fighting and had incurred heavy casualties on July 2 across the Peach Orchard, the Wheatfield, and the lower part of Cemetery Ridge.

This left the far right Confederate division under Maj. Gen. John B. Hood, whose command included Henry’s Artillery Battalion (with Latham and Reilly’s batteries, which were in position more than a mile to the west). Hood, however, had been badly wounded earlier in the assault, well before the fighting on Little Round Top began. Once Hood was removed from the field, command of the division fell to Brig. Gen. Evander Law, the division’s senior brigade commander, whose units included the attacking Alabama regiments. Law’s experience was a good example of the difficulty inherent in locating a specific officer on an active battlefield since staff officers who went in search of him following Hood’s wounding to inform him that he was now in command of the division were unable to locate him until after the fighting ceased.

Assuming someone, somewhere, recognized the importance of the hill and found their way through the chaos of battle to General Law or any other officer whose command included artillery, and convinced him of the importance of redirecting cannons to Little Round Top—any battery to whom he gave that order would have to determine how to relocate his guns, limbers, caissons, horses, and men to the summit.

Realistically, because of the steepness of the slope in places and the large boulders in others, there is only one way to do this, via the path on the eastern slope of the hill used by Union infantry and two guns of Lieutenant Charles E. Hazlett’s Battery D, 5th U.S. Artillery, to reach the crest. To do so safely, the battery would also need an escort of cavalry to shield it from Union troops along the path.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

As they neared the hill, they would have confronted 17,000 Union soldiers who by then would have been quite unwilling to allow an enemy battery to ramble past on its way to this key location. Assuming some miracle allowed their safe passage, once their cannons went into position and opened fire, those working the guns would have been immediately subject to a hellacious counter battery fire from at least four Union artillery units just north of the hill.

All things considered, and assuming the best possible circumstances favoring the Confederates, there is clearly no realistic scenario in which Southerners could have used Little Round Top to bombard the Union army at all, much less “into submission.”

It could be argued that Confederate seizure of the hill, despite its shortcomings as a base for artillery, would have given them control of the Taneytown Road, a key supply route into the Union lines that ran within several hundred yards of Little Round Top. The wooded eastern slope of the hill, however, shielded the road from view, and even if Federal commanders chose not to risk use of the road for supply wagons, there were at least two eastward roads north of the Maryland border and well south of the Round Tops that led directly to the Baltimore Pike, which was still securely in Union hands. This theory again requires more than 10,000 Yankees who had yet to be engaged in battle at all to simply allow a few hundred worn-out Confederates to continue to occupy such a key position unchallenged.

Since the Confederates never had a realistic chance of taking and holding Little Round Top once Union troops arrived there, and certainly had no way to use the hill to bombard the Union army into retreat, a failure of the 20th Maine would not have meant the loss of the battle for the Army of the Potomac. Although claims the 20th Maine “saved” the Union army at Gettysburg are unrealistic, their efforts should not be diminished.

What is important is how well the regiment performed despite a number of factors that could have caused it to fail. Apart from several dozen transfers from the disbanded 2nd Maine Infantry, Gettysburg was what one veteran called the 20th’s “first real, standup fight.” The regiment had marched nearly two dozen miles per day for a week or more but arrived on the field at Gettysburg in the early morning hours of July 2, giving them nearly 12 hours of rest before being called to action.

The 15th Alabama, by comparison, had been in every major battle in the East since the First Manassas clash in July 1861. In his memoir published in 1905, Colonel Oates recalled that he and his men had marched two dozen miles in the early part of the day to reach Gettysburg. He also wrote that soon after arriving in the position from which they would begin their assault, he dispatched two men from each company to take all of the canteens, find a water source, and fill them before returning to the regiment. According to his recollection, these men were captured and had not returned when the regiment stepped off on its movement toward the enemy, meaning they—and the regiment’s canteens—were lost for the duration of the fight.

Detailed records of the casualties of the 15th Alabama, however, do not show at least two men captured or missing in each company, casting doubt on the story. Even without abundant water, the weather in Gettysburg on that July 2 did not exceed 81 degrees under mostly cloudy skies and the humidity, according to a local professor, was “unusually low for that season of the year”—downright comfortable weather it would seem for men from hot and humid southern Alabama.

Joshua Chamberlain returned to his regiment on June 30 after a 10-day absence due to illness, likely malarial fever and dysentery that had become rampant among his men in the latter part of June. Upon his return, he learned that his promotion to colonel and command of the regiment had been approved, making him the newest colonel in the entire Union Army at that time. What he learned about warfare in 10 months since he left a professorship back home had been from books, daily drilling, and the remarkable example set by the previous commander, West Point graduate Adelbert Ames. In battle, Ames showed absolutely no fear, and Chamberlain quickly learned the value of two traits that made for a good combat commander; calmness in all circumstances and a willingness to expose oneself to danger. Every glance by a soldier back at his commanding officer that revealed a calm, confident demeanor was reassuring, and not much inspired bravery in those soldiers more than a colonel who would stand exposed among his men in the face of danger. As to drilling, the many long hours that the men spent repeatedly carrying out movements and maneuvers on various open fields near camp were rendered useless when they reached the southern end of Little Round Top with its plentiful trees, rocks, and sloping hills providing obstacles for which they had not prepared. By all accounts, Chamberlain and his men adapted well to these sudden challenges, and it probably saved many of their lives.

Demonstrating these two key qualities of command almost caused Chamberlain to lose each of his legs to Confederate bullets: the first one hitting the underside of his right foot and tearing open the arch of his boot; the second striking the scabbard of his sword hanging at his left side. The blow broke the scabbard into two pieces and badly bruised his left leg. Between these two wounds and the draining effects of his illnesses, it is a wonder the Maine professor-turned-warrior could stand upright at all at Gettysburg, much less effectively command an infantry regiment.

Had he been in the best of health, the prospect that a man trained as a professor—known as he was for handling problems with prolonged study in quiet environments—could react instantly to the battlefield situations that presented themselves, and do so effectively, is truly remarkable. Also considering his illness, wounds, and lack of combat leadership experience, Chamberlain surely would’ve been forgiven a misstep or two. When the smoke of battle had cleared, however, there was no need for forgiveness, only marvel.

Despite the challenges, which included facing a large force of battle-hardened Alabamians, Chamberlain acted calmly, maneuvered his regiment to meet each threat, and provided a stalwart inspiration to his men, even after more than a third of them had been killed or wounded.

Thanks to its elevation to mythical status over the past few decades, the real story of the 20th Maine’s work at Gettysburg is often overshadowed by the story people want to believe. This is unfortunate since the real story of personal courage, sacrifice, and ultimately success reveals a remarkable accomplishment even without the modern embellishments.

An 11th generation Mainer, Tom Desjardin has studied the 20th Maine since the age of 10. He was actor Jeff Daniels’ historical adviser for the movie Gettysburg. His The Autobiography of Joshua L. Chamberlain and The Legend of Joshua L. Chamberlain are scheduled for publication in late 2022 or early 2023.