JULY 1, 1942, was a red-letter day in the career of Brigadier General Ira C. Eaker, chief of VIII Bomber Command, the Eighth Air Force’s heavy weapons division. That was the day the first dozen Boeing B-17E bombers and crews of the 97th Bombardment Group arrived at their bases in England, finally giving VIII BC a strategic offensive capability to fight the Germans in Western Europe. Eaker wanted to show off his new unit, so he arranged an aerial gunnery display for July 29 in the presence of senior generals down from GHQ. The base was in a festive mood that morning as the officers gathered on the roof of the concrete block control tower to watch. But things did no go well. The gunners, most of whom had never operated a turret in the air, failed miserably to hit their targets, and the results embarrassed and angered Eaker.

Upon investigation he discovered the 97th’s fliers “were inept at formation flying, had little high altitude flying experience and were lackadaisical, loose-jointed, fun-loving, and in no sense ready for combat,” recalled aide and biographer James Parton. Eaker immediately fired the commanding officer and set about replacing him with someone capable of turning the group around. He had just the guy in mind—a spirited, capable 40-year-old aviator whose natural leadership talents had impressed him over the years, and whose career would be marked by making possible the impossible: Colonel Frank Alton Armstrong Jr. General Eaker called him into his office and said, “I have a small job for you. You are going to complete the training of our new heavy bomb group and lead them in combat within 16 days.” Armstrong replied, “I’ll do my best, sir.”

THIS WASN’T THE FIRST or last time that Eaker would rely on Armstrong, who made a livelihood as a “Mr. Fixit” for the general. That career path, though, didn’t appear likely in 1927, when Armstrong was living “high on the hog,” as he liked to say, as first baseman for the minor league Sarasota Tarpons baseball team, earning the princely sum of $300 a week. But the team folded at the end of the season, and Armstrong found himself facing a bleak future. While he could fall back on the law degree he had earned at Wake Forest College, the thought of spending his life writing torts and filing motions held no fascination for him. The woman who would become his wife intervened. Vernelle Hudson, a 22-year-old Virginian, made clear that she was “not about to marry a man who wanted to do nothing more with a college education than play ball.” She’d recently seen a recruitment poster that exhorted young men to “Join the U.S. Army Air Corps!” Formed in July 1926, the Air Corps was just a fledgling outfit, but full of opportunities. Armstrong had never been up in a plane, but the thought of being a flier caught his fancy. What a fine pursuit: “exciting, exacting, challenging,” he wrote in his memoir. And so in February 1928 he enlisted.

After completing basic and advanced flight training in 1929, he was assigned to a bomber group, then did stints as a flight instructor. In 1934 Armstrong flew airmail routes when President Franklin D. Roosevelt designated the army to replace private airlines in an effort to cut down fraud. It was during this tour of duty that Armstrong first met Ira Eaker, already a renowned flier, who set a world flight endurance record in 1926 and, more recently, was the first man to fly across the country “blind”—piloting an airplane purely by instruments. Eaker would go on to become the young officer’s mentor. In 1937 Armstrong earned his first Distinguished Flying Cross for safely landing a severely damaged twin-engine amphibious aircraft on a tiny, boggy clearing in Panama’s jungle fastness. The following year he took command of the 13th Bombardment Squadron based in Louisiana.

Late 1940 saw Armstrong deployed to England as a combat observer with the Royal Air Force, tasked with learning how Britain conducted its air war, from broad strategy all the way down to the minutiae of base operations and gunner training. He arrived in London that October—at the height of the Blitz. His first night in the capital proved memorable. As he wrote in his diary, “I heard the first bomb explode with a strange, sickening ‘thud.’ I don’t think I’ll ever forget that sound, or the way our hotel swayed from the shock waves.”

Recommended for you

In January 1941 Armstrong left the U.K. for reassignment as commander of the 90th Bombardment Squadron before joining the Army Air Forces’ operations branch in the Munitions Building in Washington, D.C., early the following year. Eaker’s office was one floor up. The general, who had just been given the job of establishing VIII Bomber Command, began putting together a cadre of trusted senior officers to assist him. He buttonholed Armstrong and said, “You’re going to England with me. The orders are being cut today.”

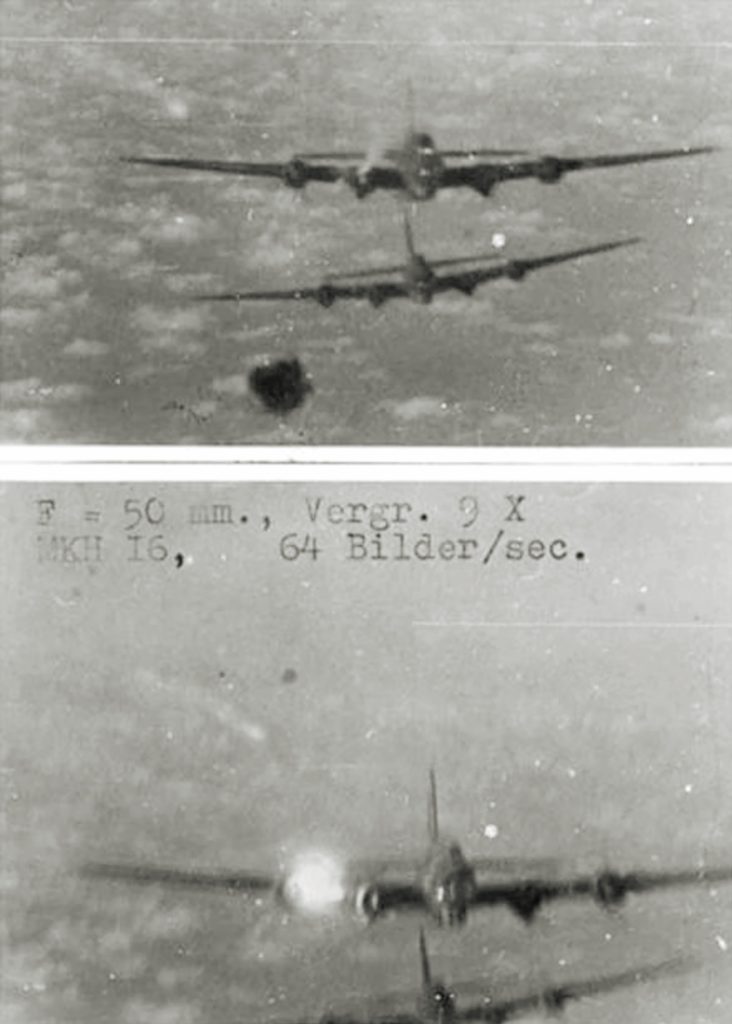

IN RESPONSE to the Blitz, in late 1941 the RAF had opened a campaign of “area bombardment” on German cities using nighttime attacks. It was not a particularly effective tactic, but the British stuck with it because they believed night bombing made their airplanes harder to target and kept their casualties to a minimum. When the advance elements of Eaker’s VIIIth began arriving in the U.K. in the spring of 1942, the RAF pushed Eaker to join forces with them on the night raids. Eaker pushed back, arguing that he had orders to employ high-altitude precision daylight bombing strikes, when targets could be seen. This strategy would take advantage of the powerful four-engined Boeing B-17 “Flying Fortress,” a plane designed with heavy defensive armament to help protect it, even during daytime raids. The “Fort,” able to carry 4,200 pounds of bombs over 2,000 miles, would soon become the Allied workhorse of the European war. But the British remained skeptical, fearing that daytime operations would mean catastrophic American losses.

Two days after the July 29 gunnery display debacle, the 97th’s new commanding officer was on the base, beginning to make his plans. In his memoir Armstrong wrote: “The 97th was in sad shape. Morale was low. Military courtesy was almost non-existent. I knew if I were to succeed in preparing this outfit for combat I would have to be tough.” And tough he was, according to Captain Paul Tibbets, a 97th squadron commander (and later of Hiroshima fame): “He had a commanding presence. He looked like the boss. He looked like a guy that had no doubt that what he was doing was the right thing.”

The next morning Armstrong gathered his outfit. He explained his role. He explained their role. He told them that if they succeeded in becoming combat-ready, they would make the Eighth Air Force’s first heavy-bomber raid from England on targets in Western Europe. That created quite a stir among the crewmen. He finished by making clear that they all had a lot of work to do.

Armstrong’s first move was ordering everybody back to school. In makeshift classrooms the airmen pored over flight manuals and watched instructional films. The next step was to get the Fortresses in the air to practice low-level attacks, flying no higher than 300 feet above the placid Northamptonshire countryside. Stern when he needed to be, the colonel made sure he flew with every pilot, putting them through their paces, criticizing or praising the performance of each. After four days the group moved their training up to 25,000 feet, where the B-17s were optimized to perform best. Armstrong used the opportunity to drill formation flying into the heads of his pilots, and to teach them the delicate intricacies of navigating in fickle European weather. The colonel threw in lots of gunnery work with towed targets. Lest their primary mission be overlooked, he made certain there were plenty of bombing exercises.

With each passing day the confidence, the morale, and the spirit of the 97th rose. On August 12, the group received orders to prepare for an August 16 raid on the sprawling, bustling railway yard and shop complex at Rouen-Sotteville, 90 miles northwest of Paris. Bad weather over the Channel at the last moment pushed the attack back by one day. The final call late on the 16th from Bomber Command stated simply, plainly—“Pull the string.” The strike was on. “I didn’t sleep much during the few remaining hours before the briefing,” the CO recalled.

The morning of the 17th, the airbase was a beehive of activity. Engines received last-minute tweaks. Planes were fueled. Bombs were fused. Guns were armed. All was in readiness for the 3:30 p.m. takeoff of the 12 B-17s heading to Rouen. Colonel Armstrong was in the lead Fort, nicknamed Butcher Shop. General Eaker flew as an observer in Yankee Doodle. Just after noon, the flight crews gathered at the operations hut for a final briefing on weather conditions. Colonel Armstrong’s remarks to his men were brief—he figured they didn’t need a pep talk this late. He told them, “I want you boys to fly as close to me as possible. I’ll be right up there in front.” When the control tower flashed the “go” signal, Butcher Shop lumbered down the runway and into the air to the cheers of ground crews, staff, and reporters lining the way.

The dozen Forts headed out over the English Channel, where they were met by four squadrons of RAF Spitfires, there to provide air cover. It was needed. German Focke-Wulf Fw 190 and Messerschmitt Me 109 fighters attacked the formation on the way into Rouen. Flying through a field of flak fired by ground batteries, the 97th’s bombers dropped 36,900 pounds of explosives from 23,000 feet. True to his word, Frank Armstrong’s Butcher Shop was the first in formation and the first to call “Bombs away!” As the group swung around and headed back to England, the Germans kept up persistent attacks on the B-17s. “Enemy fighters came at us from every figure on the clock. They bore in, holding their fire until they were within 200 yards or less, flying through our formation rolling and shooting all the while,” Armstrong said later. Belly gunner Sergeant Kent L. West got the thrill of his life when he knocked down one of the Focke-Wulfs—the first gunner in the group to score a kill. As he told a reporter afterward: “He started to climb on us from underneath. I got him in my sights and gave him a burst of 20 rounds. He went down smoking.”

The mood on the ground was jubilant when all the planes returned safely. General Eaker received credit for leading the raid while Frank Armstrong, the man who had built and led the fighting team, hung back to let his senior bask in the limelight. Eaker told reporters that all that was left of the target was “a great pall of smoke and sand.” Indeed, the 97th had done themselves, and the Army Air Forces, proud that day. More than half the bombs fell in the target area, causing serious damage to the locomotive shops. The first B-17 raid on Western Europe kicked off the Eighth Air Force’s long and successful campaign to humble the enemy.

In the coming weeks, the 97th Bombardment Group flew many missions into western France. After a particularly rough one, Armstrong posted a message of thanks to his outfit. “It is my desire that every soldier under my command feel that he had a personal interest in having placed the 97th Bombardment Group among the foremost fighting organizations the United States Air Force has ever produced…. The whole world has been astounded and amazed by our accomplishments. The 97th has made history.”

So it came as a blow to the colonel and his men when, on September 14, 1942, the 97th was seconded to the Twelfth Air Force operating in North Africa in support of the planned Allied invasion of the region. After just six weeks on the job, Armstrong returned to the States to make a two-month tour of training bases to share his warfighting experiences over Europe.

ON NEW YEAR’S DAY, 1943, General Eaker called Armstrong back into his office to inform him that he had been recommended for promotion to brigadier general. As Armstrong later recalled, “He then repeated those now familiar words, ‘I’ve got a small job for you.’”

This next “small job” was to turn around the 306th Bombardment Group (Heavy) at Thurleigh Airfield in Bedfordshire, north of London. It was much the same task as Armstrong performed on the 97th, but with a huge difference. The 97th had entered the European Theater with no fundamental experience in combat flying. The 306th, on the other hand, was a veteran of 15 missions since October 9, with a disproportionate share of losses to crew and planes, amounting to 30 percent of its original strength—the highest in the Eighth Air Force. In its three most recent raids, the group had lost nine Fortresses. A newly arrived airman asked where to put his clothes in the barracks. “Choose any bed. These guys won’t be coming back,” a quartermaster told him. After so much combat the men of the 306th had become complacent, and discipline was weak. The group stood down until Colonel Armstrong got a handle on things.

Armstrong knew his paternalistic approach with the neophyte 97th would not work with the 306th. Instead he treated the veteran group with the respect they had earned over their months at war, acknowledging their losses but promising to help the outfit reduce its casualties. He replaced several key staff officers. He canceled all leave and passes. He pushed military discipline. He set clear expectations. And he set out to establish a sense of pride in the pursuit of excellence in all tasks the group undertook. On the nitty-gritty side, the colonel instituted a rigid training schedule to make sure his flyers got lots more time in the air, drilling the basics: formations, gunnery, bomb runs. By the end of January 1943, their colonel deemed the 306th ready to return to combat. And he had something special in store for them.

January 27, 1943, didn’t feel like an auspicious day at Thurleigh. It was still pitch dark as groups of fliers trudged across the frosty ground toward the low brick building that housed the briefing room. Inside the men found seats on the backless benches that lined both sides of the narrow space. Some smoked. Some rubbed the sleep from their eyes. Most chatted about unimportant things. But despite the outward calm, anxiety was manifest. The crews knew that this morning’s mission was going to be something special. They didn’t know for sure what—just that it wasn’t going to be the usual raids on the U-boat pens at St. Nazaire or Lille’s railway yards.

Just past 4 a.m. Colonel Frank Armstrong walked briskly up the aisle to the low dais in front of the covered target map. He noticed the room was unusually crowded, and that the “tension was so great, the atmosphere could be cut with a knife,” he later wrote. And so, without ceremony, he slashed through it with one simple word: “Wilhelmshaven!” At first there was stunned silence, and then the room erupted in cheers.

Within hours those crews from the 306th Bombardment Group would be high over the North Sea, leading the very first U.S. daylight precision bombing raid on Germany itself. To be first was quite a feather in the 306th’s cap.

The attack formation included 91 bombers from six different groups, with Colonel Armstrong in the lead plane, as usual. The weather over the objective, the German navy base at Wilhelmshaven, was poor, with only occasional gaps in the clouds. When they neared the target, the Americans were swarmed by over 100 enemy fighters, but the 306th’s gunners claimed 22 shot down during the mission. As the CO promised, the group suffered only minor losses. Post-raid analysis judged the bombing accuracy as only “fair but adequate,” due in large part to the bad weather. Of larger import, though, the strike let the German people know that the Fatherland was no longer safe from U.S. bombers.

Pressmen smothered the crews upon their return. “Better than bombing the Jerries in France and a hell of a lot more satisfying,” one crewman told a young Stars & Stripes reporter, Andrew Rooney (later a correspondent for CBS’s 60 Minutes). But the quote of the day came from Colonel Armstrong, elated by the success of the attack: “I could go out and dance all night.”

Armstrong, officially a brigadier general soon after the raid, flew a few more missions with the 306th before being sent back to the States in May 1943 to lead an operational training wing, established to provide large numbers of qualified fliers to the ever-growing Eighth Air Force. In 1945 he was assigned to train and command the 315th Bombardment Wing (Very Heavy), flying B-29s. The unit was tasked with destroying Japanese fuel production and storage facilities. On August 15, 1945, just before Japan announced its surrender, Armstrong climbed behind the controls of one of the Super Forts and took off on the final heavy bombing raid of the war, a 3,800-mile round-trip run to Japan—the longest nonstop combat flight of the war. As Armstrong later noted in his memoir, he led the Eighth Air Force’s first heavy bombing mission in Western Europe and the last raid of the Pacific War—two events that neatly bookended strategic aerial combat in World War II.

The turnarounds he pulled off at the 97th and the 306th “stuck.” Both groups finished the war intact with stellar combat records to their credit.

AFTER THE WAR General Armstrong split his time between training and operational commands. He was CO of Alaskan Command in May 1961 when he was summoned to Washington about his persistent public insistence that the Department of Defense was threatening national security by cutting military resources for Alaska’s defense. The Pentagon directed the 33-year veteran to “quietly submit a retirement request.” The news stunned Armstrong. “My career was history.”

His military career may have been over, but his legacy as a leader would live on. Two colleagues at VIII Bomber Command, force historian Beirne Lay Jr. and intelligence officer Sy Bartlett, were eyewitnesses to the Eighth Air Force’s victory in the European Theater. After the war, the pair got together to write a novel about their experiences and decided to base their tough-as-nails main character—General Frank Savage—on Frank Armstrong, whom they both knew well. They called the work Twelve O’Clock High. Their bestselling book was released in 1948 and a major motion picture, starring Gregory Peck, followed the next year. Lay and Bartlett emphasized General Savage’s strong leadership skills, based directly upon their intimate knowledge of how Armstrong had successfully motivated men throughout the war.

The film, a critical hit nominated for a Best Picture Oscar, struck a chord among senior air force and navy officers as the perfect visual aid to demonstrate how leaders lead. For several decades, the service academies used Twelve O’Clock High as a treatise on effective leadership for young officers-in-training. Because of the film’s long-term impact, Frank Alton Armstrong Jr. achieved the sort of legacy that few men are ever accorded. ✯

This article was published in the June 2021 issue of World War II.