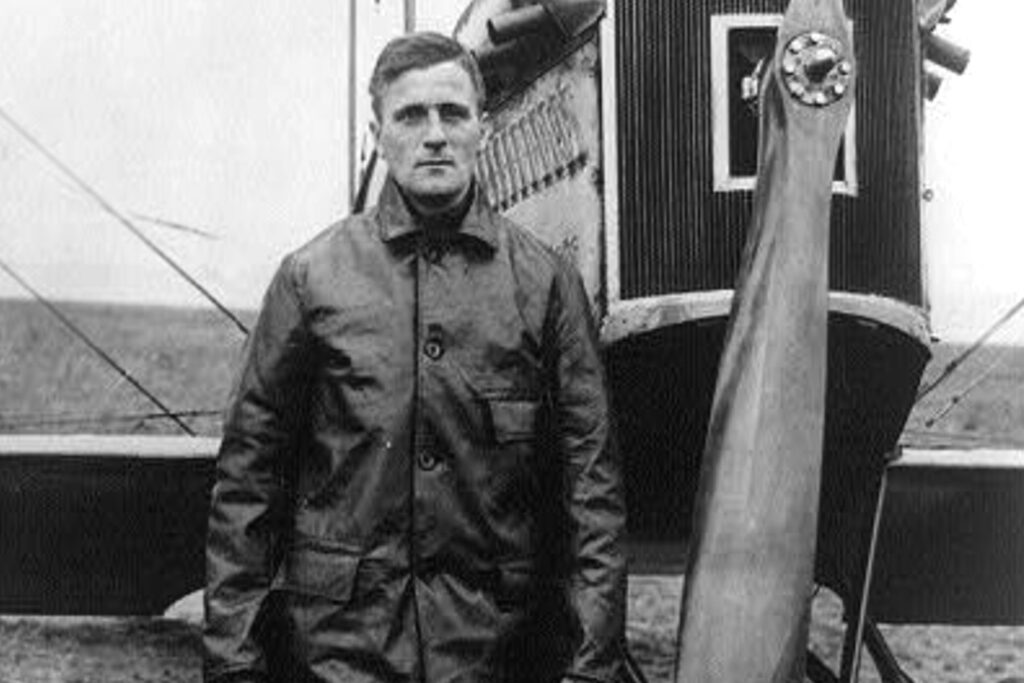

General Carl Andrew Spaatz is not well known by Americans today, yet he served as the senior air commander in the European theater after the United States entered World War II and masterminded the air strategy that helped defeat the Third Reich. A man of few words but strong convictions about the use of air power, he was also one of America’s most experienced military aviators.

Born in Boyertown, Pa., in June 1891, Spaatz graduated from the U.S. Military Academy at West Point in 1914 and was commissioned in the infantry. He served in Hawaii for a year as the white officer in charge of an infantry regiment of black soldiers. He then transferred to the Army Air Service in 1915 — a transfer that marked the beginning of a career that reached a high point during WWII and culminated in his appointment in 1948 as the first commander of the newly independent U.S. Air Force. Those interim years were filled with a wide variety of assignments that served as the ideal proving ground for the man who would eventually head the largest combat air force ever assembled and thus prove the indispensable influence of air power in modern warfare.

His last name was originally spelled Spatz, and most pronounced it “spats.” That apparently bothered his wife and three daughters, who asked him to change the spelling to Spaatz (pronounced ‘spots’) by court order. He did so in 1938. While growing up he had acquired the nickname of “Boz,” but that changed to “Toohey” during his West Point days because of his striking resemblance to a redheaded upperclassman named F.J. Toohey. That nickname stayed with him for the rest of his life, though the spelling was later shortened to “Tooey” by everyone who knew him.

Spaatz’s flying days began at the Army Air Service flying school at North Island, San Diego, Calif., in November 1915. He reportedly soloed after only 50 minutes of instruction. His first assignment after graduation the following May was at Columbus, N.M., with the 1st Aero Squadron, which helped General John J. Pershing try to chase down Francisco “Pancho” Villa in Mexico in 1916. The pursuit was an exercise in futility, as the squadron’s underpowered Curtiss JN-3 Jennies deteriorated during the mission, doing little except underline the sad state of American military aviation. But the time in Mexico was a valuable learning experience for Spaatz and the Air Service, as the United States entered the war against Germany in 1917. It served as a wake-up call for America that its ragtag air force was not ready for a war in the air anywhere.

Spaatz was sent to France as a major in September 1917 and put in charge of training pursuit pilots for combat at the Air Service’s largest in-theater advanced flying school, at Issoudun. He found a high rate of accidents there; living conditions were horrendous, morale low and discipline lacking. He became base commander and established different phases of flight training at 10 auxiliary fields in spite of the winter mud and construction difficulties.

Spaatz built up a vigorous flying program with 32 different types of aircraft, including 17 different models of the French Nieuport pursuit plane. He improved conditions to the point where he was able to put on an impressive 100-plane airshow for General Pershing and Secretary of War Newton D. Baker in the summer of 1918. Spaatz’s ability to overcome great obstacles caught the attention of his superiors, even though he always maintained an unpretentious low profile. His record showed that he was a ‘doer’ and a problem-solver who got results without fanfare. As a result, he was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross.

Spaatz wanted practical combat experience before the war ended, and he managed to attach himself to the 13th Aero Squadron, flying French Spads at the front for two weeks. He went on several patrols and was officially credited with shooting down two German Fokkers in September 1918. After the second kill, he stayed too long in the battle area and, out of gas, had to crash-land his Spad in no man’s land. The plane was wrecked, but Spaatz, unhurt, was helped to safety by French civilians.

The Air Service organized the Transcontinental Reliability Endurance Flight in October 1919, and Spaatz won it flying west to east in a Curtiss SE-5. He spent the next two years rotating to peacetime assignments at San Diego, Fort Worth and San Francisco. In 1921 he was made commander of the 1st Pursuit Group at Kelly Field, San Antonio, Texas, the only pursuit unit in the Air Service at the time, followed by duty with subsequent units at Ellington Field, Texas, and Selfridge Field, Mich. Along the way, he learned how imperative it was for air leaders to be able to solve technical and personnel problems as well as develop tactical improvements. He graduated from the Air Service Tactical School at Langley Field, Va., where the role of pursuit aviation was emphasized.

The concept of an independent air force was a subject of much discussion among airmen after the end of World War I, along with the theory of strategic air warfare, whereby air units would attack an enemy’s vital military resources far behind the front lines. This was in conflict with the Navy’s concept of its responsibility for aerial defense of the nation’s coasts against invaders. The Army view was that aircraft were meant to back up its troops and not go far ahead of the battlefield to bomb rear area enemy targets such as armament factories, rail centers and airfields. To both services, an independent air force was totally out of the question.

The Air Service experience in Europe had proved otherwise to Brig. Gen. William “Billy” Mitchell and others who believed that an air force should be separate from and co-equal to the Army and Navy. Spaatz agreed with Mitchell’s theories, helped him prepare his defense when he was accused of publicly criticizing superiors who had hindered the development of America’s air power, and also testified forthrightly on Mitchell’s behalf at his 1925 court-martial. He was tagged from then on as a courageous advocate of air power, along with future generals Henry H. “Hap” Arnold, Ira Eaker, Jimmy Doolittle and others.

By this time the lean-jawed, red-haired Spaatz had also established himself among his contemporaries as a man who was gruff in manner, direct, unassuming yet ever mindful of the well-being of the men who served under him. Ira Eaker described his friend as “a miser with words” who was fond of saying, “I never learned anything while talking.” He had a knack for summarizing a viewpoint with sardonic, rhetorical questions that were quote-worthy and sometimes irreverent. At a battleship christening, he asked, “How are we going to get it up in the air and drop it on Tokyo?” When he first heard about the plan to put men on the moon, he quipped, “Who’s the enemy on the moon?” When he toured St. Peter’s cathedral after Rome was captured by the Allies in World War II, he commented that it “would make a fine dirigible hangar.”

In the 1920s, pursuit (later called fighter) aircraft were considered by many airmen to be the principal weapon of air warfare. Others believed that bombers could not be intercepted by short-range fighters, as was demonstrated by an air exercise at Wright Field, Ohio, in 1931. However, during maneuvers at Fort Knox, Ky., in 1933, Captain Claire Chennault — who later exercised his theories in China with the so-called Flying Tigers — showed that bombers could be attacked by fighters day and night at all altitudes.

Spaatz believed that bombers were the essential nucleus of an air force for eventual victory, while fighter aircraft could give front-line aid to ground troops. During the interwar period, Spaatz made many trips to McCook Field, in Dayton, Ohio, serving as a member of technical boards and committees. The experience served to broaden his view of the problems of building a viable, balanced air force. He found that the Navy as well as the ground-oriented Army branches would be persistent antagonists in the struggle for military appropriations for an independent air arm.

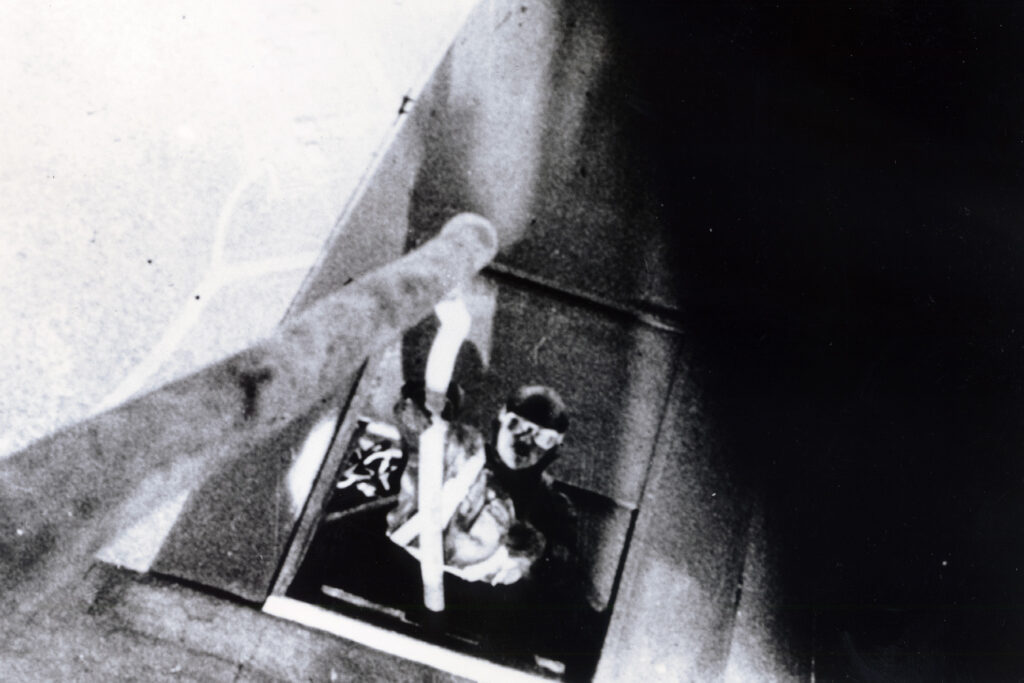

The Army Air Service (renamed the Army Air Corps in 1926) engaged in a running public relations battle with the Navy by setting aviation speed, altitude and endurance records that always garnered favorable publicity. One of these was the endurance mark set in 1923 by Captain Lowell H. Smith and Lieutenant John P. Richter, who kept their de Havilland DH-4B aloft for more than 37 hours with aerial refueling. Not much more attention was paid to aerial refueling as a method of extending the range of aircraft until 1929, when Spaatz commanded a flight in the Fokker C-2A Question Mark with four other crew members. By aerial refueling they managed to keep the plane in the air for 150 hours and 40 minutes. During one part of the flight, Spaatz was splashed with fuel. His crew mates stripped him down and lathered him with zinc oxide to prevent burns, after which he told them that if he had to bail out, they were to continue the mission. In the end, he stayed aboard — “wearing only skin cream, goggles, a parachute and a grin,” according to one historian.

Question Mark’s mission was considered a great achievement at the time. It demonstrated that bombers could take off with lighter loads of gas and heavier bombloads but could increase their range considerably by refueling in the air. However, nothing was done for many years to apply that capability to Air Corps operations.

It was a given in the 1920s that bombers were always slower than pursuit planes and had to be protected by them en route to and from target areas. But by the 1930s, the speeds of bombers and fighters were comparable, and it appeared that the bombers would soon exceed the ability of short-range fighters to escort them. If that developed, it was reasoned that bombers must be equipped to protect themselves. Spaatz testified before the Baker Board in 1934 that a choice for future bomber development had to be made: Design a long-range plane for bomber escort duty or provide more armament for bombers to protect themselves. The latter choice was adopted, and twin-engine bombers were developed with protective firepower, followed by a demand for four-engine bombers. The Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress and Consolidated B-24 Liberator were to provide the answer. The primary use of such heavy bombers would be to destroy the economic fabric of an enemy nation by precision bombing of specific vital war industries.

While the Air Corps battled for appropriations, Spaatz developed a deeper friendship with contemporaries like Arnold, Eaker, Doolittle, Hoyt S. Vandenburg and others who shared his developing views about the employment of aircraft in warfare. He was promoted to lieutenant colonel in 1935 and attended the Army Command and General Staff School at Fort Leavenworth, Kan., where he encountered the doctrine that aircraft units were to be employed under Army control only as an auxiliary to the infantry, cavalry and artillery. Never fond of spending time in a classroom and not pleased with a curriculum that ignored the potential of air power, he graduated close to the bottom of the class, with the recommendation from the Army instructional staff that he not be considered for future staff assignments.

Air Corps personnel officers ignored that recommendation. His next assignment was to Langley Field, Va., for a 2 1/2-year tour with the 2nd Wing of the General Headquarters Air Force, organized as a separate combat arm within the Air Corps. This was the premier unit of bombers, pursuit and reconnaissance aircraft that was developing training, logistical and technical improvements as the basis for future operations. At that juncture the first Flying Fortresses were being delivered, and Spaatz was aboard the first one to land at Langley Field in 1937.

In November 1938 his friend Hap Arnold, now a major general and chief of the Army Air Corps, transferred Spaatz to Washington as chief of plans to prepare for the expansion of the military forces for a war in Europe that started when Adolf Hitler’s forces invaded Poland in September 1939. Promoted to colonel, Spaatz went to England in mid-1940 as an observer during the Battle of Britain. His enthusiasm for the development of strategic bombardment grew with emphasis on precision high-altitude daylight bombing as the principal means to conquer the Nazi juggernaut that was overwhelming France. That concept had to be tested and proved.

The Army Air Corps was renamed the Army Air Forces in June 1941, and Arnold appointed Spaatz, promoted to brigadier general, as the first chief of the Air Staff. It was a vital assignment in which he oversaw the construction of airfields, the training of aircrews and the innumerable logistical details that had to be accomplished to build an expanded air arm. After Pearl Harbor thrust the United States directly into the war on a global scale, the Eighth Air Force was established on January 28, 1942, and a small group of officers moved to England to study the methods of the Royal Air Force (RAF) and plan for future operations from English bases. Spaatz was promoted to major general and assigned to head the Eighth with Brig. Gen. Ira Eaker as his deputy. When he arrived in England, Spaatz let it be known that the Eighth Air Force would be committed to daylight bombing efforts, despite the RAF and the Luftwaffe having converted their bombing operations to night missions because of the unbearably heavy losses to fighters and anti-aircraft fire in daytime. There was much official and unofficial criticism, but Spaatz and Eaker would not be dissuaded. The decision was made: The Eighth would precision-bomb by day, and the RAF would area-bomb by night. The initial target priorities were:

- German submarine construction yards and pens

- Germany’s aircraft industry and the Luftwaffe

- Transportation

- Oil plants

- Other targets in the enemy’s war industries

This general order was followed until the end of the war but was altered when circumstances required.

Two heavy bomb groups had arrived in England by August 1, 1942. They successfully flew their first mission on August 17, taking no casualties. It was followed with three more attacks. Although there was much enthusiasm over the results, the jubilation was short-lived; at that juncture the 12th Bomber Command was being formed in North Africa, and the Eighth was being depleted to supply it with planes and crews. Priority had been given to supporting the Allied armies in their efforts to drive the Axis forces out of North Africa.

The Anglo-American forces invaded North Africa on November 8, 1942, with General Dwight D. Eisenhower in command. Spaatz was promoted to three-star rank and assumed command of all American air forces in the European theater; Eaker became commander of the Eighth. Spaatz faced many difficulties in his new assignment, not only with the enemy but also with the coordination of RAF and American Air Forces operations. The solution was to integrate the American and British air operations as quickly as possible. Of course, the French air force also had to be included after their surrender. The Northwest African Air Force and the Mediterranean Allied Air Forces were created to solve the question of operational control of the air effort during the African and Mediterranean campaigns. They contributed much to the surrender of Axis forces in North Africa and the invasion of Italy.

Meanwhile, Spaatz was thinking in terms of having two major strategic air forces established to attack the war-making German infrastructure from two general directions: the Eighth from England and the Fifteenth from Italy. The Eighth would concentrate on transportation, supply and manufacturing targets in France and Germany; the Fifteenth could attack the vital oil fields in Romania. Spaatz’s proposal was approved by the Combined Chiefs of Staff.

Spaatz was transferred to England after the German surrender in North Africa to command the U.S. Strategic Air Forces. Eaker was transferred to the Mediterranean, and Doolittle, who had commanded the Twelfth Air Force there and then briefly the Fifteenth, was assigned as commander of the Eighth.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt and Prime Minister Winston S. Churchill had decided that the invasion of German-held Europe would be made across the English Channel to the French coast. If the strategic air power concept was to be proved in that offensive, it would be by attacking and destroying targets deep inside Germany, thus depriving the enemy of the supplies needed to confront the invading Allied forces. The bombers and their escorting fighters would have to penetrate fierce anti-aircraft fire and a strong shield of Luftwaffe fighters to reach German supporting facilities.

The key to a successful policy of daylight precision bombing was the introduction of long-range fighters that could escort B-17s and B-24s to those targets in Germany and back. When the Americans arrived in England, the range of their Bell P-39 Airacobras and Curtiss P-40s was only 150 miles. Later, the early models of the Lockheed P-38 Lightnings and Republic P-47s could only escort 350 and 250 miles, respectively. Drop tanks later added more range, but not enough. It was the North American P-51 Mustangs, with an 850-mile range from their English bases, that made a significant difference. They could escort the bombers all the way to Berlin. Field Marshal Hermann Gring reportedly admitted later that when he first saw Mustangs over Berlin, he knew Germany had lost the war.

Soon after Doolittle arrived to take over the Eighth Air Force, he sought Spaatz’s approval to change the procedures followed by the escorting fighters. Their original assignment was to protect the bombers on the way to and from their targets and not leave them, but Doolittle envisioned a more aggressive role.

Doolittle stated his rationale for the change in his memoirs: “Fighter pilots are usually pugnacious individuals by nature and are trained to be aggressive in the air. Their machines are designed for offensive action. I thought our fighter forces should intercept the enemy fighters before they reached the bombers.” Spaatz approved of the change in the fighters’ mission, and Doolittle then told Maj. Gen. William E. Kepner, commander of the 8th Fighter Command, to “flush the enemy out in the air and beat them up on the ground on the way home. The first priority of the fighters is to take the offensive.” Doolittle said it was the most important and far-reaching decision he made, and Spaatz endorsed, during the war. The fighters’ altered mission was controversial because the bomber crews thought they were being abandoned, but it proved to be a turning point as the subsequent air battles began to decimate the Luftwaffe trained pilot force. Gring said it was demoralizing when “the umbrella fighters, after escorting the bombers, would swoop down and hit everything, including the jet planes in process of landing.”

Meanwhile, Spaatz launched ever larger bomber forces against Germany. Most noteworthy was the period of February 20-25, 1944, known as the ‘Big Week,’ in which the enemy aircraft industry was the major target for the Eighth Air Force. More than 3,800 bombers were engaged, and more than 800 U.S. fighters, plus fighters from 16 RAF squadrons, headed for 12 major assembly and component manufacturing plants. The Allied losses that week totaled 226 bombers and 28 fighters versus more than 600 German fighters. The results were a “conspicuous success,” according to Spaatz in a report to Washington. The intensive campaign crippled the Luftwaffe and drained strength from the Eastern Front, helping the advancing Red Army. Meanwhile, continuing blows against the oil industry targets by the Fifteenth Air Force proved the wisdom of attacking that target category. Plans for the invasion could now proceed, with Allied forces expecting to gain air supremacy over the French beaches.

But there was much more strategic work to be done after the invasion began. General Eisenhower, supreme commander of the Allied forces, believed destruction of the German rail system should be given priority, to hamper transportation of supplies and ground troops to the battle areas in France. Spaatz, however, thought the synthetic oil industry should be given priority, because he believed its destruction would bring the German war machine to a halt much sooner. The British, on the other hand, wanted Spaatz to divert his forces to bomb the German launch sites from which V-1 missiles were being fired at England. The result was a compromise. Two attacks were made on synthetic oil refineries before the invasion, then V-1 and V-2 missile sites were bombed after D-Day, followed by an attack on the large rail yards at Hamm, a vital German marshaling center. Secret German messages intercepted by the Allies showed that the greatest impact was caused by the strikes against the oil targets. The Luftwaffe found it could not fly at will, and the army’s panzers were being stalled in their tracks. Thus, the oil industry stood as a primary target for the rest of the war.

By the fall of 1944, the combined British and American air power strength totaled 14,700 aircraft, including 4,700 fighters, 6,000 medium and heavy bombers, and 4,000 planes of other types, such as troop carriers and utility-type aircraft. Despite the introduction of German Messerschmitt Me-262 jet-powered and Me-163 rocket-powered interceptors that startled the Allies, the growing Allied air forces against them were overwhelming. By April 1945, there were few strategic targets left. Allied aircraft roamed all over Germany at will and turned to helping the ground forces clear the roads to Berlin.

Spaatz knew that his insistence on following the principle of strategic air warfare, as he saw it, had paid off. However, “it could not have won this war alone,” he said, “without the surface forces. It was won by the coordination of land, sea and air forces. Air power, however, was the spark of success in Europe.”

Spaatz was present when the Germans surrendered at Reims on May 7, 1945, and two days later when they surrendered to the Russians in Berlin. But the war was not over for Tooey Spaatz. He and his staff had been developing plans to redeploy American air forces in Europe to the Pacific. Transfer of aircraft and personnel of the Eighth Air Force began on May 20, 1945.

Spaatz returned home briefly to take part in victory celebrations in Philadelphia and Reading, Pa. He then returned to England, expecting to manage the demobilization effort there, but General Arnold was not satisfied with the way things were going in the Pacific and ordered Spaatz to return to Washington.

Meanwhile, the atomic bomb had been successfully tested and plans were being made to use it against Japan. Spaatz was briefed on the weapon and was assigned to help work out details on how it would be used if the Japanese did not surrender. But there was a question of command in the Pacific. American forces were commanded by General Douglas MacArthur in the South Pacific and Admiral Chester Nimitz in the Central Pacific. The challenge facing the Americans in the Far East was far different from the air and ground war in Europe. There was much more Navy involvement there, and a different set of personalities were in charge. The question was: Who would control the air power effort against the Japanese homeland?

One of the main concepts that General Arnold had adopted for the employment of strategic and tactical air power was that it should be centrally controlled and not fragmented among ground and sea commanders. To avoid the question of who should exercise control of the Boeing B-29 Superfortresses assigned to the Twentieth Air Force — MacArthur or Nimitz — Arnold persuaded the Joint Chiefs of Staff that he should control their operations from Washington. Spaatz was the man he chose to manage the operations of the U.S. Army Strategic Air Forces in the Far East and report directly to him. His mission was to conduct land-based strategic air operations against Japan, meant to progressively destroy and dislocate the country’s military, industrial and economic system to a point where her capacity for armed resistance was fatally weakened.

The B-29s had been operating first from India and China beginning in 1943, but without good results. They were then sent to Guam, Tinian and Saipan in the Marianas as those areas became available. The hope was that their use would compel the Japanese to surrender without an invasion by ground and sea forces. If not, Spaatz was authorized to use the first atomic bomb against Japan, which was dropped on Hiroshima on August 6, 1945. He had insisted on having a letter from President Harry Truman specifically authorizing his use of the atomic bomb and that MacArthur and Nimitz must be advised. When there was no word of surrender after the attack on Hiroshima, Spaatz directed that warning leaflets be dropped, followed by several non-atomic attacks. When there was still no indication of capitulation, he ordered the second bomb dropped on Nagasaki on August 9, effectively ending the war.

The surrender was signed aboard the battleship Missouri in Tokyo Bay on September 2 as 1,500 Navy planes and nearly 500 B-29s roared overhead. Spaatz, who was there, was thus privileged to be the only American general officer to have been on hand at the three major Axis surrender ceremonies. In retrospect, he commented: ‘It is interesting to note that Japan was reduced by air power, operating from bases captured by coordination of land, sea and air forces, and that she surrendered without the expected invasion becoming necessary.’

General Arnold retired in February 1946, and Spaatz was appointed commanding general of the Army Air Forces. He immediately engaged in a new battle against the Army and Navy to establish the Air Force as a separate service, coequal with the Army and Navy under a secretary of defense. It could only be done by convincing Congress that it was vital to national defense and had been thoroughly proved in war. Spaatz, meanwhile, restructured the Army Air Forces by creating commands based on major functions, such as the Air Defense Command, Strategic Air Command and Tactical Air Command, along with supporting commands.

The Navy and the Marine Corps fought for the status quo, fearing that the Air Force would take over their aviation requirements. The Army wanted its own air arm, to assure that its airlift and close air support needs would be under its control. General Eisenhower, then chief of staff of the Army, and President Truman favored the unification idea, but the congressional debate went on for months, and several bills were introduced before a compromise was worked out. President Truman signed the National Security Act of 1947 and Executive Order No. 9877, defining the functions and responsibilities of the three armed forces, on July 26, 1947. The official birth date of the U.S. Air Force was September 17, 1947, the day that former Missouri senator W. Stuart Symington was sworn in as the first secretary of the Air Force. Spaatz was appointed the first Air Force chief of staff. The battle for equal status begun by Billy Mitchell after WWI had finally been won.

Spaatz immediately began to make the organization work. He had successfully used the “deputy system” in Europe, whereby deputy chiefs of staff were responsible for operations, material, personel and administration. In March 1948 he hammered out with his Army and Navy counterparts an agreement as to how the roles and missions of each service would be carried out. Two months later, at age 57 and with 34 years of continuous service, not counting his West Point cadet time, he requested retirement.

Carl Spaatz spent the next 13 years working as a military affairs editor for Newsweek. He died on July 14, 1974, at age 83.

Unlike many of his contemporaries, Tooey Spaatz maintained his low-profile image to the end and never wrote his memoirs, since he thought that would be too self-serving. He is buried at the Air Force Academy in Colorado Springs, Colo., a symbolic gesture that recognizes Spaatz’s long commitment to the creation of the Air Force as a separate military service and his dedication to making it come about.

This article was written by C.V. Glines and originally published in the March 2002 issue of Aviation History. For more great articles subscribe to Aviation History magazine today!