The joint American-British Independence Day 1942 air raid was a costly start to the Eighth Air Force’s European bombing campaign…but it was a start

It was a beautiful sunny day in England on July 11, 1942, as the crew of the Douglas Boston mark III light bomber stood stiffly at attention in their best theater dress uniforms. U.S. Brig. Gen. Ira C. Eaker watched as Maj. Gen. Carl A. “Tooey” Spaatz made his way down the line, pinning medals on all of them. The bomber’s commander, Captain Charles C. “Keg” Kegelman, was the first recipient of the Distinguished Service Cross in the Eighth Air Force, while his crew, Lieutenant Randall Dorton and Sergeants Bennie Cunningham and Robert Golay, were all awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross for their July 4 mission. Kegelman was also promoted to the rank of major, effective immediately.

Major General Dwight D. Eisenhower, commander of all U.S. troops in Europe, had read Kegelman’s after-action report upon the latter’s miraculous return and then wrote in pencil across the page, “This Officer is hereby awarded the Distinguished Service Cross.” Shaking his head, the astonished Eisenhower looked up at his aide and asked, “Are all of the reports going to be like this one?”

Kegelman’s unit, the 15th Bomb Squadron (Light), had docked in Wales on May 13 and been swiftly transported by train to Grafton Underwood, a cleverly hidden Royal Air Force base near Kettering, England. The airfield was entirely covered in ankle-high grass with swaths cut through it to resemble cultivated farmland. The illusion was further enhanced by full-scale replicas of black-and-white Holstein cows randomly scattered across the area.

Several pilots were dispatched on June 4 to RAF Swanton Morley to gain operational experience before conducting their own forays. Early on, Lieutenant Howard Cook tried to tell airmen of the resident No. 226 Squadron how to fly low. This advice did not go over very well and the men of the 15th were sent back to their base two days later. Not all of the British had their feathers ruffled by the bold Americans. Harry Castledine of 226 Squadron noted: “The Americans were a really wild lot, but great fun. I was told they played cowboys and Indians in the woods around Bylaugh Hall with live ammo! At the All-Ranks dances you might think that they would win a jitterbug contest, but a lot depended on the partner and the WAAFs [members of the RAF Women’s Auxiliary Air Force] were not so experienced.”

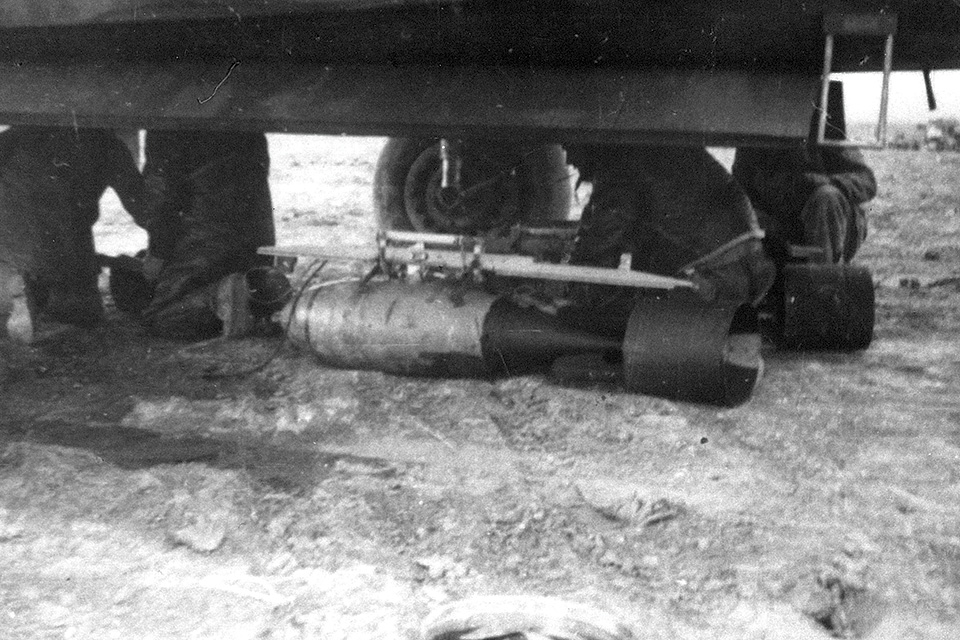

On June 6 the RAF loaned the Americans A-20 Havocs (called Bostons by the British), twin-engine airplanes on which they had already trained. Almost immediately tragedy struck, however, as the 15th suffered its first casualties. One of their bombers hit a high-tension wire mid-flight, killing two crewmen. Nine four-man flight crews and 36 ground personnel were eventually sent back to Swanton Morley for extensive instruction. One of the hardest parts of training was learning the intricate system for identifying friendly planes in England’s crowded skies, especially in silhouette. The airmen were trained in low-level bombing using sunken ships along the shore as well as vacant fields as targets, simultaneously honing their gunnery skills.

Along with Kegelman, Captains Bill Odell and Martin Crabtree had been commissioned officers for two years and had each logged more than 1,000 hours of flight time. In his diary, Odell wrote, “Our junior pilots, like [Leo] Hawel, [Fred A. “Jack”] Loehrl and [Stan] Lynn had completed flying school in December, 1941.” Not mincing words, Odell explained that the British wing commander, J.H. Lynn, surely recognized “we knew and flew the Boston aircraft better than his own [squadron].” He further noted, “Wing Commander Lynn advised his superiors that aside of providing the initial baptism of fire, his ability to further the Americans’ pre-battle education was limited. They [the Americans] could be turned loose anytime and be perfectly confident of finding their way around in the dark.”

The Bostons’ Wright R-2600-A5B Twin Cyclone engines propelled the bombers to a little over 300 mph in a pinch and their large fuel tanks enabled them to fly long-range missions. These agile aircraft could not destroy an entire industrial plant, but they were very effective in damaging airfields and dispersing troop concentrations. The 97th Bomb Squadron’s Lieutenant James Wash recalled the Bostons’ advantage of “surprising ground defenses and presenting difficult targets to enemy fighters.”

Back in Washington, D.C., political leaders clamored for some type of demonstration to be made against the Germans on the European front. “After seven months of war, they were eager for evidence of American air power,” Wash noted. “The blitz-wearied British and the folks back home in the United States badly needed a shot of good news.”

President Franklin D. Roosevelt declared that Independence Day would be honored “not in fireworks of make-believe, but in death-dealing reality of tanks and planes and guns and ships.” What more fitting way to commemorate the United States’ separation from Great Britain than to bring both sides together in a joint operation? Roosevelt further observed how important it was to “not waste one hour, not to stop one shot, not to hold back one blow—that is the way to mark our great national holiday in this year of 1942.” With his subordinates kept in the dark, U.S. Army Air Forces Commanding General Henry H. “Hap” Arnold had written to Prime Minister Winston Churchill promising that American and British airmen would be fighting together by July 4.

Orders came through on June 28 to Eaker and Spaatz for them to begin combat operations on Independence Day. The two generals were both aghast and protested against the directive, to no avail. Despite the military’s advice, some sort of dramatic event, much like Jimmy Doolittle’s Tokyo raid back in April, was going to happen to satisfy the politicians, who knew it would likely have a positive effect on American voters. Eaker’s aide, James Parton, recalled his boss “argued that a quickie out of England would accomplish no real damage, risk heavy losses and hurt the morale of his tiny command.”

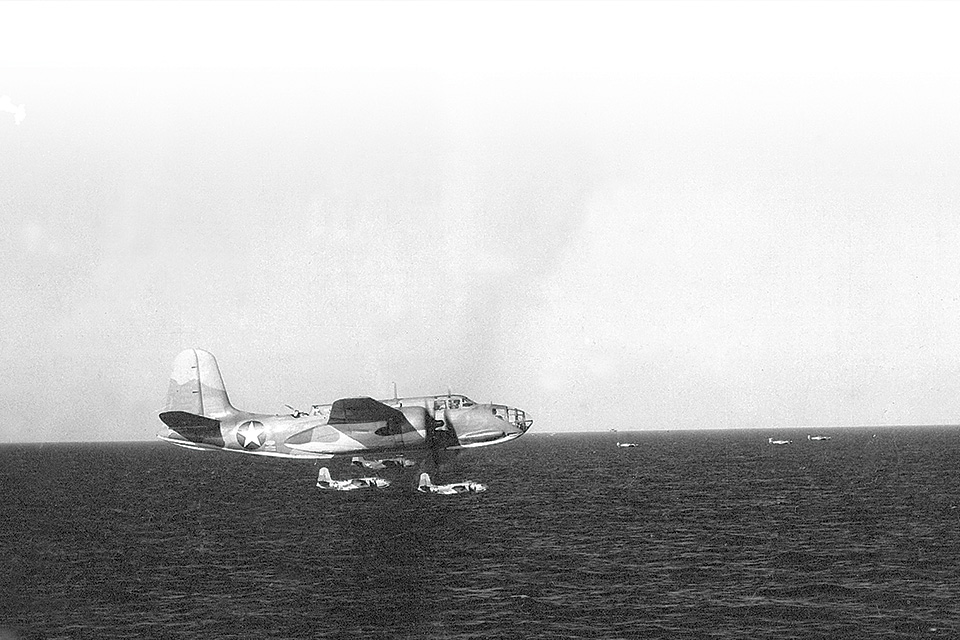

As neither the Eighth nor the RAF had any planes available for the 97th Squadron, it was an easy choice to use the 15th since it had both the local training and the loaned bombers on hand. The British roundels on the six borrowed Bostons were quickly painted over with the USAAF’s white star to boost American morale.

The British had already scheduled a raid with 12 Bostons of 226 Squadron on June 29, and substituted Kegelman and his crew for one of theirs. This would be the first time that members of the AAF took part in European bombing operations. The mission’s targets were the marshalling yards and other military facilities at Hazebrouck, France. All of the Bostons managed to get through the mission unscathed, though their escorts lost three planes. Bombing between 12,500 and 13,000 feet, the formation recorded several hits on the rail lines and adjoining buildings. In the process Kegelman and his crew accrued some valuable combat experience for their upcoming mission.

Given the short time available for organization, Eisenhower, Eaker and Spaatz all visited the 15th at Swanton Morley in late June. They gave directions in person for the bombing runs and took time to shake hands with the airmen. As they would only be using six American crews paired with the equivalent number of British ones, Hawel recalled: “On July 1st, Captain Kegelman put all nine pilots’ names in a hat. Six were marked with a ‘yes’ and three marked ‘no.’ I drew a ‘yes’ and later discovered I was one of six American pilots who would fly the famous 4th of July raid over Holland. The six pilots drawn were Captains Kegelman, Crabtree and Odell and Lieutenants Lynn, Loehrl and myself.” The next day, Eaker and Spaatz returned and spoke at length with Kegelman. On July 3 the intelligence officer for VIII Bomber Command, Harris Hull, came by the airfield to give the men their first combat briefing.

“Just shows you how much our brass hats know or how they value the cost of men’s lives,” wrote Odell in his diary.

The men of the 15th thought it peculiar that they were garnering such attention for a raid that the British had conducted many times before. Odell mirrored the other airmen’s feelings when he wrote, “It seemed a little ironic that they [the RAF] had been pressed into taking part in an American Independence Day celebration commemorating the severance of ties between our two countries.” But as AAF airman Francis Chartier noted, “Our national holiday was just another day to our allies in England.”

Four airfields in German-occupied Holland were selected as targets and the attacking force was separated into four three-plane formations. The first objective along the shore of Holland was De Kooy, which was to be bombed by 226 Squadron Leader Shaw Kennedy, followed by Americans Kegelman and Loehrl. The second target was Bergen Alkmaar, with an assaulting force of 226 Flight Lt. Ronald A. “Yogi” Yates-Earl and Pilot Officer Charles M. “Hank” Henning along with the 15th’s Lieutenant Lynn. The third site to be attacked was Valkenburg with the lone British crew of Squadron Leader John Castle in addition to the 15th’s Crabtree and Hawel. The final flight was directed at Haamstede, led by 226 Flight Lt. A.B. “Digger” Wheeler and Pilot Officer A. “Elkie” Eltringham, with Odell bringing up the rear.

At 5:15 on the morning of July 4, the pilots and crews were awakened and served coffee in the airfield’s mess hall before heading to the operations room. “We turned in our papers and got packed for the combat flight (concentrated food, water purifier, compass and French, Dutch, German money),” Odell later documented. “More dope on the trip and then out to the airplane. Had no trouble but was a bit anxious on take off.” Eisenhower returned to the field to send off the 15th, recalling, “To mark our entry into the European fighting I took time to visit the crews immediately before the take-off and talked with the survivors after their return.” He understood the public ramifications of the raid while participants such as Odell tried to downplay the historic date and concentrate solely on the mission at hand.

The first Boston lifted off at 7:09 a.m., with the rest of the formation taking off five minutes later. “Take off time was to be early in the hope of catching the German defences off guard,” wrote RAF Swanton Morley historian and airman Stephen W. Pope. The raiders would fly across the North Sea at low level to avoid detection. Once they reached the Dutch coast they would split up and attack their assigned airfields.

In Kegelman’s plane, Dorton remembered how graceful they looked trundling across the grass field against the dawn. “As we flew over the English countryside [toward] the coast, farmers already at work in their fields waved to us as our ships roared over their heads at less than 100 feet,” he wrote in his journal.

“After getting in the air we settled down and flew right on the trees to the coast,” recalled Odell. “Felt a little uneasy, because there was a cloudless sky but no fighters appeared.” As they approached the Dutch coast, Dorton noticed “yellow-sailed fishing boats a mile to their left. That was unlucky as the Germans kept observers on off-shore boats.”

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

Wheeler’s section reached Haamstede just before 8 a.m. Close behind him flew Eltringham and Odell. The Bostons raced across the airfield at 20 to 100 feet above ground, dropping 500-pound general purpose bombs with time-delay fuzes and incendiaries. Hits were made on administration buildings, a hangar and dispersal points. Odell unleashed his inner daredevil during the bomb run, maneuvering his plane sideways while flying between two hangars and strafing smaller targets near the runway. Wheeler used his nose guns to good effect, shooting up 160 German airmen in their flying kits gathered in a crowd for roll call. Additionally, the rear gunners of all three planes managed to score some casualties on their way out of the area. As the formation left the target area, smoke was seen rising over the southeastern section of Haamstede.

The Bergen Alkmaar contingent led by Yates-Earl arrived at their destination at 8:02. They had difficulties in identifying the proper objective, causing the formation to attack at 100 feet in line astern, starting fires in hangars located on the north side of the field. Lynn’s plane was hit by flak right after bombing and crashed on the airfield, killing all on board in a fiery eruption. Henning safely left the area after his bombing run, only to be shot down 15 miles off the Dutch shore by a Focke-Wulf Fw-190 flown by Sergeant Johannes Rathenow of Jagdgeschwader 1.

The Valkenburg attacking force found themselves too far south after hitting the coast. Castle’s bomb bay doors jammed and he was unable to drop his bombload. Americans Crabtree and Hawel waited in vain for Castle to open his doors. “We were so low I saw two young ladies eating breakfast right out of my side window,” Hawel said. Finally, the two Americans used their machine guns to strafe the airfield and disperse three Messerschmitt Me-109s, setting one on fire. All three Bostons returned with their full complement of bombs.

“I noticed numerous lines of splashes walking out to meet us,” Dorton reported on their approach to De Kooy, “and it was hard to realize they were bullets striking the water. The closer we got, the more splashes there were and suddenly Kennedy veered sharply to the left. Now our engines were wide open and we shot across the land at close to 300 mph. We were jinking about violently, so close to the ground that a gun trying to fire at us hit a German soldier on a bicycle. He flew straight up into the air and the cycle rolled on down the road.” The gunfire was getting heavier and tensions rose as Dorton recalled: “We twisted over violently and I heard Sergeant Cunningham scream, ‘Loehrl hit the ground…he’s breaking all to pieces!’ At the same moment our plane gave a tremendous lurch and we hit the ground. We skidded along for a sickening moment and then the captain [Kegelman] pulled her nose up and we were pointed straight at an old structure that looked like a windmill without sails. There were guns mounted in it and they were firing.”

As Kegelman’s Boston skidded on the ground, Sergeant Golay yelled, “Give ’em hell, Cap!” Golay saw a propeller fly by “and I thought Bennie had got a Messerschmitt. Then I saw smoke and looked out and saw it was our propeller and I didn’t feel so happy anymore.”

The bomber’s starboard engine had been hit by flak, causing the prop to shear off. “I was wondering what to do when I heard Golay shout,” Kegelman reported. “I thought we were goners but somehow Golay’s shout made me try to pull us out.” The captain managed to keep the Boston aloft by jettisoning its bombload.

“Then our nose section jumped and shook as Kegelman fired our forward guns into the flak tower,” remembered Dorton. “I thought we would ram it but Keg lifted a wing over [it] and then dove between the banks of a canal heading for the North Sea.

“I looked to the right and saw that the shell that had knocked us to the ground had sheared off the forward section of the right engine, prop and all. Gas was pouring out of the fuel line and burning as it hit the hot cylinders. Luckily, our airspeed with one engine was enough to blow out the flames.”

“It was a long 140 miles home, but they made it,” said Wash. “When the plane finally parked and the bomb bay doors were opened, Netherlands soil fell out on the tarmac.” Kegelman’s bomber was the last to touch down and despite only having one engine made a safe landing and taxied to the control tower. Inspection of his aircraft revealed scratch marks on the Boston’s belly where he had obviously touched the ground.

“All the brass were on the field with us, anxiously awaiting the captain’s return,” recalled AAF airman Eben W. “Wright” Holloway. “A great cheer arose when Keg’s plane finally came hobbling in.” Eaker was present when Kegelman landed, congratulating him and the other crewman. Hull handled the debriefings for the flight crews. Eaker called Eisenhower, who was relieved to hear of the bombers’ return but concerned about the losses.

The positive press generated by the attack soothed the politicians in Washington. The Washington Post gave front-page billing to the raid with the headline “Yanks Raid Nazis In Holland” and The New York Times opined, “The attack was no holiday stunt.” Despite the loss of three planes—two American and one British—and most of their crews (the bombardier on Loehrl’s Boston, Lieutenant Marshall Draper, miraculously survived and became the first Eighth Air Force POW), the mission was deemed a success. On the British side of the Pond, RAF officials applauded their allies. They described the 15th’s joint mission with them as a “daring event which, occurring on July 4, symbolized American ability once more to strike for freedom!”

Richard H. Holloway is the 15th Bombardment Squadron’s historian and the son of one of its members, Eben Wainwright “Wright” Holloway. Suggested reading: We Were Eagles, Volume 1: The Eighth Air Force at War, July 1942 to November 1943, by Martin W. Bowman; and The Mighty Eighth: A History of the Units, Men and Machines of the U.S. 8th Air Force, by Roger A. Freeman.

Interested in our opening painting by Nixon Galloway? Your own signed print is only a click away!

This feature originally appeared in the July 2021 issue of Aviation History. Subscribe today!