A band of well-heeled altruists described as “Harvard grads, glamour boys & career men” left behind charmed lives to man ambulances for the Armed Field Service.

IT WAS A CASE that captivated America. “Youth is Hunted in Kidnap Scare,” blared the headline in the New York Times on December 16, 1935. Within hours J. Edgar Hoover and 30 of his G-men were hunting those responsible for abducting an aspiring actor, Caleb Jones Milne IV, from a New York street. The next day Milne’s grandfather, a textile tycoon, received a ransom note for $20,000; as the FBI technical laboratory scrutinized it for clues, the search intensified. Four days later Milne was found bound and gagged in a ditch about 40 miles from Chester, Pennsylvania. But he was alive.

Hoover denied the ransom had been paid and told reporters that his bureau was investigating “important clues” in their hunt for the kidnappers. He kept to himself some inconsistencies in Milne’s story, but the young man eventually broke under questioning.

“The 24-year-old heir to a textile fortune confessed that his kidnapping was a hoax,” reported the Washington, D.C., Sunday Star on its December 29 front page, before explaining that Milne was “inspired by need of money and by a belief that resultant publicity would help him get a job on the stage. His confession, made to Government agents early, was followed within a few hours by his arraignment on a charge of attempted extortion.”

Nearly six years later, on November 15, 1941, the same newspaper carried a much smaller story tucked away on its inside pages. Headlined “Actor Disinherited for Kidnap Hoax,” it reported that in a codicil to his will the recently deceased textile tycoon, Caleb J. Milne Jr., stipulated that he had been unable to forgive his grandson for his wicked hoax and that he would not receive a cent of his $431,000 estate [about $8 million today].

By then, the younger Milne had long since put the shameful memory behind him. The charges against him had been dropped shortly after he admitted to the hoax, but his acting career was finished. He returned home in disgrace to a forgiving mother and matured into a man with a different set of values, in which pacifism was central. “Knowing you so well, I wish that I could send you some jolly reassurance that everything will be all right,” he wrote to his mother on the eve of his departure overseas as a volunteer medical worker. It was June 1942, and his ship was scheduled to sail from New York in a matter of days. “You are familiar with my general outline of ideas, so let’s just say that what will happen, will. Experience and human adventure have as much importance if they are disastrous or crippling, as when they are purely pleasant or optimistic.”

When the United States entered the war in December 1941, there had been no question of Milne following his father into the U.S. Marine Corps. “I am not sure of my reasons,” he wrote his mother in addressing the question of why he had instead joined the American Field Service (AFS)—an all-volunteer medical unit whose members drove ambulances and carried stretchers on the battlefield, tending to the wounded whatever their nationality.

“I am not foaming to bayonet anyone, nor am I embittered enough to throw precious life away for this momentary calamity that has spread like a disease over the world,” wrote Milne. “I believe our side is somewhat ‘righter’ in all truth, but it is hard for an open mind to clog with hate…. I dream of the day when one may say, ‘I am a citizen of the world.’”

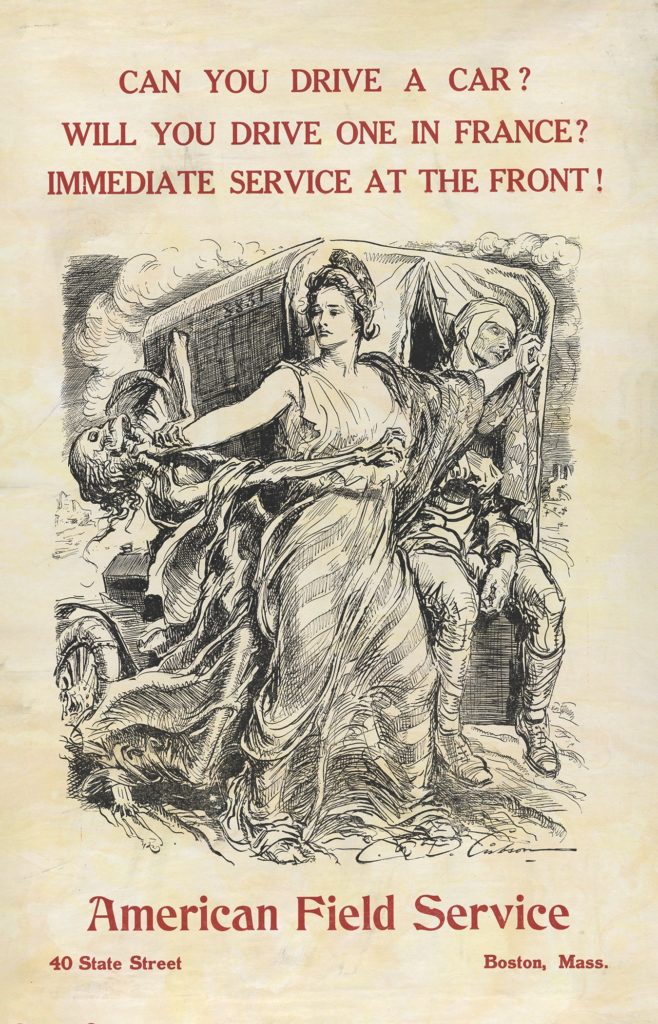

For a man of such beliefs, the AFS was a natural choice. Formed in 1914 in France as an ambulance service, the AFS and its corps of volunteers had performed valiantly on the Western Front. Following the war, the organization dedicated itself to strengthening cultural links between France and the United States. On the outbreak of World War II, it reverted to an ambulance unit; its first set of volunteers left New York for France in March 1940. “The British and French have got to win because they are not extremist,” one of the volunteers said when he arrived in Paris on April 3. “I can’t bear a world in which the extremist will win.”

The AFS was involved in the 1940 battle for France—but following the country’s capitulation in June, the unit was disbanded and their equipment handed over to the American Red Cross. Then, in February 1942, the AFS returned to the front line to “do their bit” for the free world against Nazi extremism as a new contingent of volunteers, designated “Unit 1,” arrived in North Africa and were attached to the British Eighth Army as they fought the Germans and Italians.

Milne belonged to the largest contingent yet, the 16th Volunteer Unit, numbering 100.

“The Group is an interesting mixture of people, thank God,” Milne, 30, wrote his mother, once they were at sea aboard a swift Danish cargo cruiser. “I’d say twenty-eight is the average age although we have one who must be sixty.”

Many shared Milne’s pacifism. Among the youngest was Henry Bonner, a 19-year-old undergraduate at Harvard, who had enrolled in the ship’s poker school early in the Atlantic crossing. Another youngster was Porter Jarrell, 23, who had been a journalist in New York for Musical Record before joining. A war zone didn’t seem a natural fit for Jarrell, a conscientious objector and a poor physical specimen with flat feet and weak eyesight.

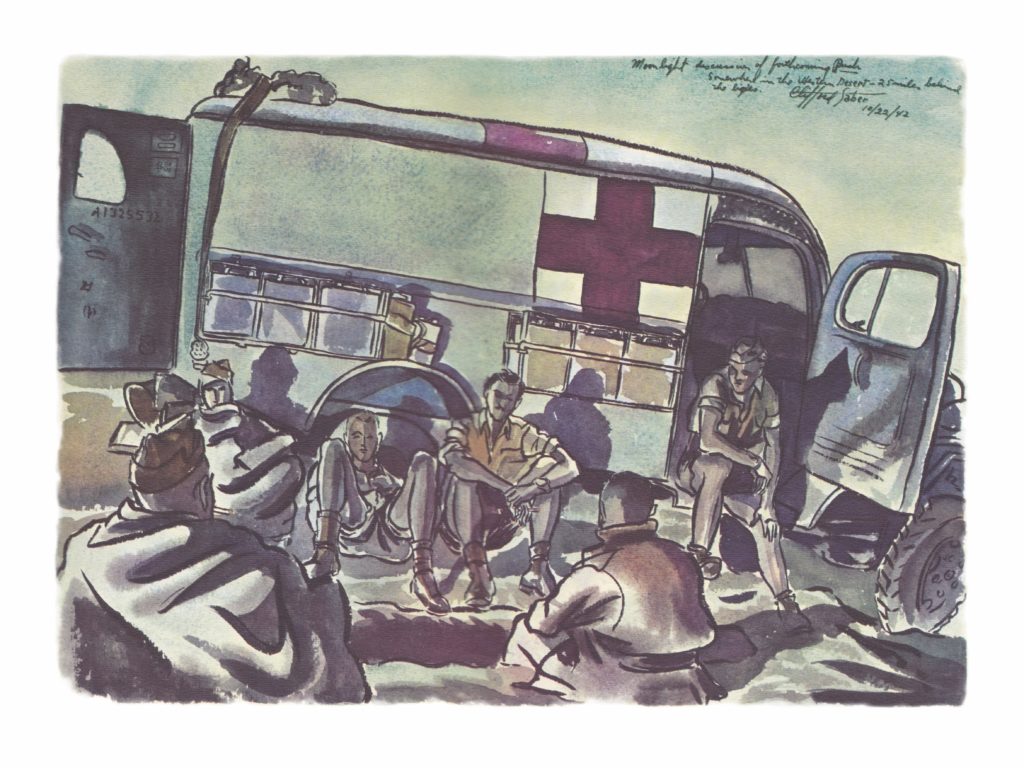

Clifford O. Saber was different. A mural painter before the war, Saber, 28, had served eight months in the 29th Infantry Division in 1940 before securing a temporary release from service—something permissible before Pearl Harbor. Eager to become a war artist, Saber had volunteered for the AFS because it offered him the swiftest route to the front line. There was no inner torment about the morality of war for Saber; he was having too much fun.

“At times the voyage was reminiscent of a peacetime cruise,” Saber recalled of the volunteers’ route across the Atlantic. “We had the run of the boat, food was excellent and plentiful, the weather pleasant enough for swimming and sunbathing.”

Mornings on ship were devoted to physical fitness, first aid, map reading, and language classes, and there were daily lectures on a diverse range of subjects. Evenings were spent in the bar, singing, talking, and playing poker. During this time, Saber sketched pen portraits of all his new comrades.

Now that Milne had had more time to acquaint himself with his fellow volunteers, he told his mother they were like a “gypsy caravan full of Harvard grads, glamour boys & career men. But nearly all of them easy to get along with, and congenial.” His only concern, he confided, was whether they were cut out for what awaited them in North Africa. “Few of the fellows have ever known responsibility or adversity, or faint heart.”

Rather, they were idealists and romantics whose privileged lives had, in most cases, shielded them from destruction and violence. Beneath the confident façade of each volunteer was the nagging anxiety of what awaited them in North Africa, and how they would cope. Those were thoughts that haunted them all—as surely did, too, the realization that by the law of averages not all of them would return home.

THE MEN OF THE 16TH Volunteer Unit arrived at Port Tewfik, Egypt, on September 6, 1942, where they were welcomed to North Africa by Colonel Ralph Richmond of Boston, the officer in charge of the AFS in the Middle East, and Captain Andrew C. Geer, whom Saber described as “a dead ringer in looks for Dick Tracy.” Geer was the unit’s commanding officer, and word soon got around that not only was he a veteran of the desert war but that in his youth he had sparred with professional boxers Jack Dempsey and Gene Tunney.

The AFS had by then earned a reputation for courage and fortitude on the battlefield. The previous June at the Battle of Bir Hakeim, a strategically important oasis in the Libyan desert, they had lost 12 ambulances and two volunteers while tending to the wounded of the Free French. Their actions won praise from General Charles de Gaulle, as they had from the 2nd New Zealand Division, with whom the AFS had served during the Battle of Alam el Halfa in August in Egypt. Colonel Pat Ardagh, in command of the division’s Mobile Surgical Units, had written to Colonel Richmond to convey a “genuinely warm and sincere appreciation of everything done by the officers and men of [the AFS], whom we consider it an honor to have had with us.”

The Battle of Alam el Halfa had ended in defeat for German field marshal Erwin Rommel’s Panzer Armee Afrika. His armor failed to outflank the British, who were dug in on a firm defensive line at a place called El Alamein, north of Alam el Halfa. For the new commander of the Eighth Army, Lieutenant General Bernard L. Montgomery, the victory had marked a turning point in the North African campaign. Montgomery surmised (correctly, as the Battle of Alam el Halfa was as far east as the Germans got) that Rommel had punched himself out. Now Montgomery began planning his own attack, Operation Lightfoot, scheduled for October 23, 1942.

Trucks transported Milne and his comrades to their transit camp at El Tahag, about 40 miles from Cairo, and the AFS’s two-week training program began the following day. The volunteers had all passed first-aid exams on the ship; now they were schooled in desert navigation, convoy driving, land mine avoidance, ambulance maintenance, and the British Army medical system.

At the end of the training, the deputy director of medical services inspected the volunteers and their ambulances. He was delighted with what he found and informed the men that, as of now, the 16th Volunteer Unit no longer existed: it had been absorbed into the 15th AFS unit, serving with the British Army’s 567th Ambulance Car Company in the Royal Army Service Corps.

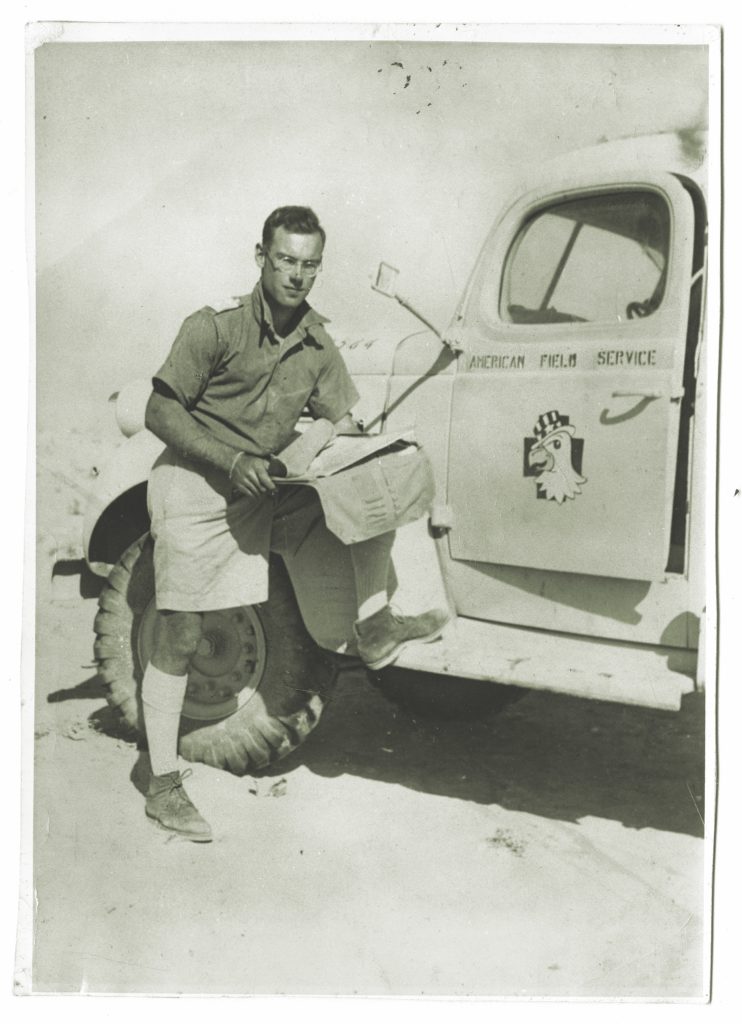

Proud as they were of their designation, the 15th were prouder still to be the sole American representatives in the Eighth Army. Geer commissioned Saber to design an insignia for the unit: a “wild, cocky, bald-headed eagle wearing an Uncle Sam hat against a red-cross background,” as Saber put it, that was emblazoned on the door of every ambulance.

The ambulances were American-made Dodges. “There are two brown leather seats forward that pitch up if wanted,” Milne told his mother. “Behind them a space of nine feet, two padded benches hinged on either side and four stretchers folded up, a toolbox, fire extinguisher, opening-out doors and a let-down step on the rear. The ceiling has two lights, a wire ventilator and fan.”

The 15th AFS was divided into six subsections, each comprising five ambulances, five drivers, a spare driver, a driver-mechanic, and a noncommissioned officer. Not only was the AFS taking shape, but so was the war—which, for Milne, had become less abstract, he explained in a letter home. “I feel now that there is more sense to this conflict,” Milne wrote, “not because of the old clichés and speeches, but simply because of listening to the thoughts of men.”

WHAT HAS BECOME KNOWN as the Second Battle of El Alamein began on the evening of October 23, 1942, with a thunderous artillery barrage from 1,000 Allied guns. More than two weeks of brutal fighting followed, during which time the Eighth Army first emasculated the enemy’s infantry before moving on to its armor. “The battle is coming to an end and I’m sorry to say it is not to our own profit,” Rommel wrote to his daughter, Trudel, on November 4, as German troops began retreating west toward Libya.

The 15th AFS was deployed along the front line, where they collected wounded Australians, Highlanders, New Zealanders, Free Frenchmen, and any enemy they encountered. They drove casualties back to an evacuation hospital whose three wards could handle 600 patients. Once treated, the severe cases were transported farther east to hospitals in the Egyptian cities of Alexandria and Cairo.

“Our prime concern was to get these men back for further treatment without causing them additional pain or damage,” Clifford Saber recalled. The primitive desert roads “were hub-deep in dust which covered the holes and ruts; we drove slowly, sometimes at a crawl…. When we had unloaded, we raced back. Our work was to be steady for the next week or so but not as rushed as it was the first two days and nights.”

The stoicism of the soldiers they loaded into their ambulances deeply impressed the Americans. The more badly wounded received morphine doses, but others—those with “lucky” wounds—sat in the back of the ambulance and spoke with the euphoria of survival. “What good sports most of them are,” Caleb Milne wrote. “I feel a very real sense of brotherhood in this work…. It is sad that this relationship comes as the result of catastrophe rather than the remedy for it.”

Throughout November, the Eighth Army pursued their enemy across the Egyptian border into Libya—while 2,000 miles farther west, American and British troops invaded French Morocco and Algeria. Allied troops had the Axis forces in a vice, although it would take six more months before they were squeezed into surrendering.

As the 15th AFS advanced west with the Eighth, they began to encounter more of the enemy. In a letter to a family friend—celebrated American composer and music critic Deems Taylor—Milne wrote of a young German soldier he had recently delivered to a field hospital who had left in his ambulance a book entitled An Introduction to Mozart. “I am writing you of this incident not as a sentimental episode,” Milne explained, “but to send to the Philharmonic the gratitude and the hungry welcome that will always greet great music wherever, and whenever, civilized men are listening.”

Such rays of civilization were rare, however, as the Eighth Army drove on toward Tripoli, the Libyan capital. The AFS was subjected to enemy barrages and, most feared of all, aerial attacks. “I was taken by surprise when a flight of Stukas, black and evil in the sunlight, swooped upon us,” wrote Milne in January 1943. “For some inane reason I jammed my coat-collar up and pulled my head down tight into my shoulders as the dark body swooped at me. It zoomed with a mighty roar over my head and I saw the sand lift and snap in a sprinkle of machine gun bullets. Then it was gone.”

AFTER 1,400 MILES OF HARD SLOG, the Eighth Army entered Tripoli on January 23, three months to the day since the start of the El Alamein offensive. “We hurried into the city and had a few drinks of vino in celebration,” Saber recalled, “then descended upon a horse-drawn carriage with an Italian driver and demanded the keys to the city.”

The Axis troops still had plenty of piss and vinegar despite their withdrawal into Tunisia. Between them and their pursuers was the Mareth Line, a chain of blockhouses stretching 22 miles inland from Zarat, on the east coast, to the Matmata Hills in the southwest. Erected by the French before the war as a deterrent to Benito Mussolini’s Italian forces, they were now manned by the First Italian Army—which included many veteran German formations—and presented a serious obstacle to Montgomery’s Eighth Army.

They attacked on March 20; three days later, Clifford Saber’s luck ran out. “His ambulance was strafed from the air by a low-flying enemy aircraft about 8 miles north of Medenine,” reported Captain Arthur Howe Jr., who had risen through the ranks from ambulance driver to section leader. “One bullet came through the roof of the car and hit Saber in the back of the head. His spare driver, William Schorger, took over the car, which had not been damaged.”

A surgeon saved Saber’s life. Nothing, though, could be done for ambulance driver Randy Eaton, 21, when he was hit by a shell on March 25. “He died instantly, without pain,” wrote Lieutenant Charlie Snead in the platoon diary. “The whole crew are severely shocked. He was a good lad and a good driver.”

Milne knew Eaton only in passing, but his death exacerbated the grief he had been feeling since March 22 when his mechanic—a jolly young Englishman attached to the AFS—was killed in a bombing by a German fighter plane. “It was such a jolt to see so good a mixture of vitality and smiles and health reduced with such ghastly abruptness,” Milne told his mother. “But, as I have always felt, the pain exists only for the bystanders. I don’t understand life, so naturally death seems very simple to me.”

By March 29, 1943, the Germans and Italians had been forced from the Mareth Line, and by the middle of April the Eighth Army had taken the city of Sfax on Tunisia’s east coast, 170 miles southeast of the capital city of Tunis. The fighting in the following weeks was bitter as the enemy exploited the mountainous terrain inland from Enfidaville, just 50 miles south of Tunis, to make a final stand. But Tunis fell on May 7, and the AFS were the first Americans inside the capital. Now all that remained by way of German defiance was what Australian war correspondent Alan Moorehead described as “a large knot of resistance in the mountains between Zaghouan and Enfidaville.”

Remnants of the Germans’ battle-hardened 90th Light Africa Division were dug in on the high ground. Their mortars had inflicted many casualties on the New Zealanders occupying the slit trenches below, and on May 9, General Philippe Leclerc’s Free French Forces replaced the Kiwis. The French troops counted among their number 20 men from the 15th AFS, all of whom had responded to a request for stretcher-bearers.

The French opened their offensive at 5:15 on the morning of May 11. As their artillery sought the Germans on the mountains, the enemy mortars responded in kind. Porter Jarrell and another AFS volunteer, Robert J. F. Lindsay, were attached to the French Foreign Legion’s second battalion, which had successfully seized an enemy observation point on a small peak. Down in a ravine, though, the German mortars were inflicting heavy casualties on the Legion’s first battalion. Jarrell knew that his friends Caleb Milne and Henry Bonner were with them and set off to assist. “The 1st Battalion had been suffering from the same mortar barrage as we had, but the effect was more costly,” he recalled.

Jarrell—who in 1944 would be decorated for gallantry by British Special Forces for rescuing two wounded men while under aerial attack—found Bonner bleeding from a shrapnel wound to his back. Then, from above, Jarrell heard a cry for help. He scrambled over the scree and discovered Milne and the French soldier he had been tending when a shell exploded.

“I took a brief look at the Legionnaire and saw there was very little chance for him, since he had severe head and abdominal wounds,” Jarrell said. “Milne seemed in good condition, considering that his left leg was badly cut by shrapnel and the foot broken at the ankle.” A calm Milne explained to Jarrell that he had also received “a small piece in his back.” Ignoring the continuing mortar barrage, Jarrell applied a tourniquet and gave his friend a shot of morphine. Then, with the help of Lindsay and a second AFS man, Jarrell loaded Milne onto a stretcher and carried him down the mountainside.

That evening Jarrell received a visit from a Lieutenant Martineau, the medical officer of the 1st Battalion. He had good and bad news: Bonner was going to be fine. But despite the efforts of two surgeons, it had not been possible to save Milne. It hadn’t been such a “small piece” of shrapnel after all. Martineau offered his condolences. “Milne was so evidently a gentleman,” he told Jarrell. “He did his work better than any other probably because he was a better man than any other.”

The following day the French took the mountain. A May 13 entry in the 15th AFS war diary reads: “Five ambulances and personnel relieved of duty with the Free French Corps.” The dry notation didn’t do the moment justice. Captain Thomas O. Greenough, who had replaced the repatriated Captain Geer as the unit’s commanding officer, came up from battalion HQ to commend Jarrell and his colleagues for their gallantry. As the Americans boarded a truck for the trip back to base, Greenough recalled, the “hard-bitten Legionnaires themselves saluted them when they left.”

THE BRITISH HONORED MILNE by covering his coffin with their flag as they lowered him into the ground at a scenic spot close to the sea and within sight of the mountain on which he had been mortally wounded.

In the U.S., however, his valor was met with indifference. In reporting Milne’s death—one of 36 AFS men to die in the war—the newspapers were more interested in reminding their readers of his youthful indiscretions. “Hoax Kidnap Figure is Killed in Tunisia” was the New York Times’s headline.

What would Milne have thought? He had traveled a long, occasionally painful road to redemption, and the experience had made him a better man. In a letter he wrote for his mother in the event of his death, he asked her not to grieve. “I am not in the least unhappy for myself, and I beg of you not to be,” he said. “It has been, and is a vivid, amazing, wonderful world so full of winter and spring, warm rain and cold snow, adventures and contentments, good things and bad—that the experiences already crowded into my days have answered every wish and need of mine for fullness and plenty…. I do not want to live forever—the past has been splendid enough in the intricacies of living which I have so loved.” ✯

This article was published in the August 2020 issue of World War II.