These nine artists lost their lives on or near the battlefield as they tried to record the realities of war for faraway audiences.

James R. O’Neill

During the American Civil War, Irish-born James R. O’Neill, who at one time or another made his living as an actor, comedian, or landscape artist, worked for Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper as an artist-correspondent in the war’s Western theater—especially Oklahoma, southern Missouri, Arkansas, and Kansas—sending reports, cartoons, and the occasional sketch to the home office in New York City. Even before entering the fray, O’Neill had been painting scenes of the war copied from engravings he had seen in Leslie’s for a panopticon (a large panorama) that was first exhibited in October 1861. The only sketch that bore his signature—of a Union cavalry charge at Honey Springs, Indian Territory (Oklahoma), on July 17, 1863—was published in Leslie’s some five weeks after the battle.

In early October 1863, O’Neill found himself near Fort Baxter, a small Union post in Kansas, as he traveled with a Union detachment accompanying Major General James G. Blunt. On October 6, a band of Quantrill’s Raiders under the command of William T. “Bloody Bill” Anderson attacked the fort, but its defenders repulsed the Confederate guerrillas. Moving out into the prairie, Anderson’s forces, disguised as Federal soldiers, found Blunt’s detachment and virtually wiped it out, summarily executing and scalping those they captured, including O’Neill. He is the only artist known to have been killed during the Civil War.

Frank Vizetelly

Frank Vizetelly, a veteran pictorial journalist of the American Civil War and the Austro-Prussian War, traveled to northeastern Africa in 1883 for The Graphic, a London weekly illustrated newspaper, to cover the war in Sudan against Mahdists in that country who were attempting to overthrow Anglo-Egyptian rule.

In November, an Anglo-Egyptian force of more than 10,000 men under Colonel William Hicks was led into an ambush by treacherous native guides and completely defeated. The Europeans were either slaughtered or subsequently massacred by the victorious Mahdi, though it was rumored that Vizetelly had somehow survived. Subsequent military intelligence confirmed tales of a lone white man—a captured British artist—living in the Mahdi’s camp. British authorities searched high and low for him, even seeking the aid of a priest who had been in Khartoum, but the leads were false: The prisoner turned out to be a German scientist. As late as June 1887 people thought Vizetelly might still be alive, and one person claimed to have seen him in Khartoum. Authorities circulated photographs in hopes of finding him but later concluded that the various sightings were mistaken.

Vizetelly’s fate remains unknown.

Vassili Vereschchagin

When Vassili Vereschchagin arrived at Port Arthur, China, in 1904 during the Russo-Japanese War, Admiral Stepan Osipovich Makarov invited the famous artist to join him aboard his battleship, Petropavlovsk, the flagship of the Russian fleet in the Pacific, to observe a series of naval exercises and maneuvers. In his final letter to his wife on March 30, Vereschchagin noted that he had been on the ship and was eager to see battle. Japanese ships they had sighted had sunk two Russian ships near Port Arthur. Makarov discouraged the artist from staying on board, but Vereschchagin insisted. With six other ships, the Petropavlovsk headed out to sea and soon engaged the Japanese. After a brief fight, the latter headed farther out to sea to draw the Russians toward a much larger Japanese fleet. Realizing his predicament, Makarov ordered his ships back to Port Arthur, but 2 miles offshore the Petropavlovsk hit a mine, igniting its ammunition hold and setting off a much larger explosion. Vereschchagin, who was standing near Makarov, continued sketching. A third explosion sank the ship, and its 700-man crew—along with Vereschchagin—perished. Miraculously, Vereschchagin’s last work, a picture of a council of war presided over by Makarov, was recovered almost undamaged.

Eric Ravilious

When World War II broke out in September 1939, Eric Ravilious volunteered to be a part-time air spotter with Britain’s Royal Observer Corps, but the day before Christmas he was notified that he had been accepted by the War Artists’ Advisory Committee. At 36 he was already an established artist, having designed murals and exhibited many paintings and watercolors. Two months later Ravilious, now an honorary captain in the Royal Marines, was stationed at Chatham Dockyard in Kent, sketching the military activities of the Admiralty. In May 1940 he was on board HMS Highlander, a British destroyer, covering the Battles of Narvik and the Allies’ subsequent evacuation of Norway. Over the next few months he traveled around Britain, recording various military scenes. In August 1942 he flew to the Royal Air Force station at Kaldadarnes, in Reykjavik, Iceland, and the following month went on a mission to search for a missing plane. Three Lockheeds were sent out to search for the missing aircraft; his failed to return to the base. Ravilious and the plane’s four-man crew were never found.

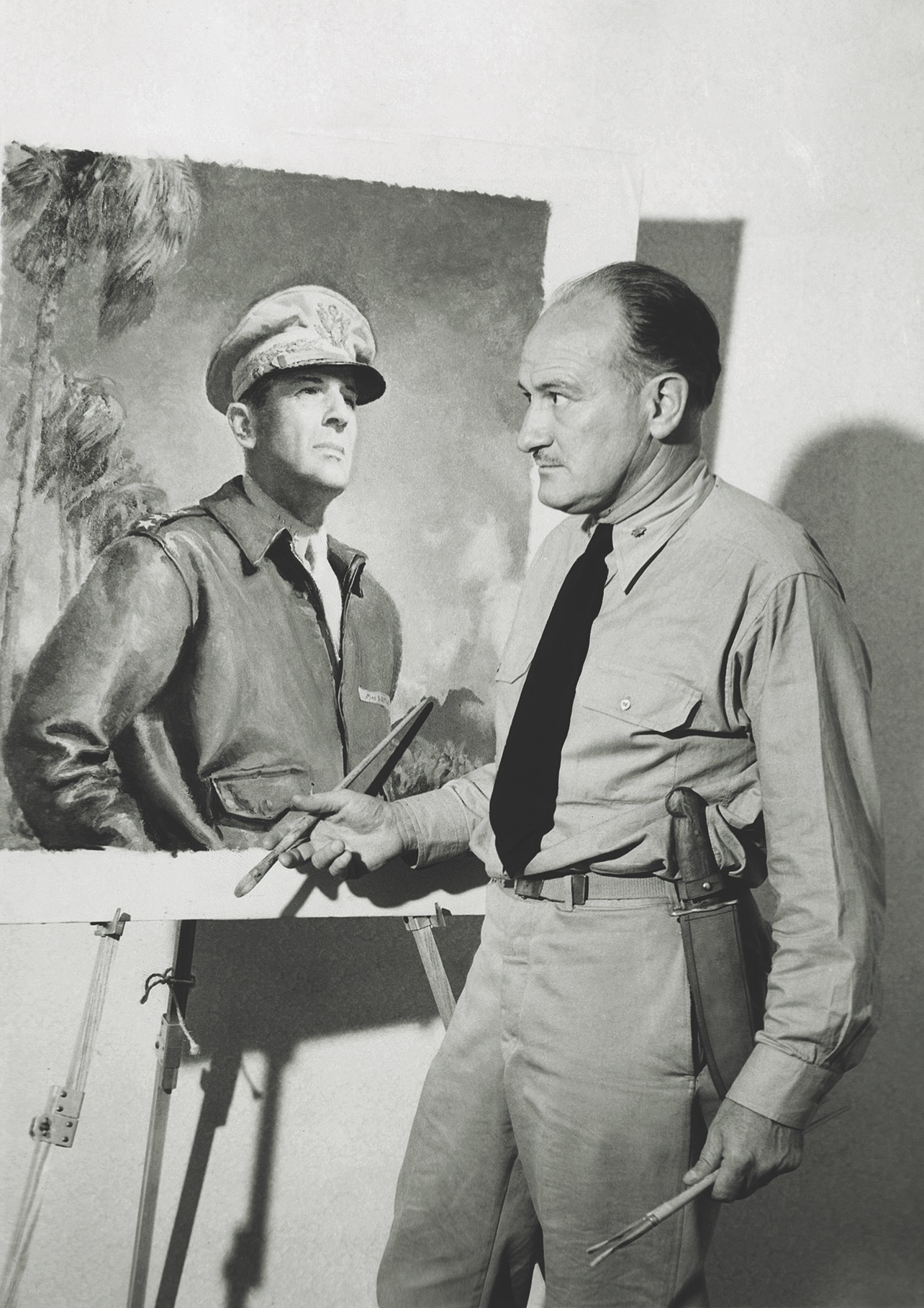

McClelland Barclay

Although McClelland Barclay, who was commissioned in the U.S. Naval Reserve in 1938, was 50 years old when the Japanese attacked the U.S. naval base at Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, he was immediately called up for active duty. An established artist who had created recruiting posters for the navy, developed camouflage patterns, and designed the Navy and Marine Corps Medal, he immediately sought a position as an official artist, arguing that he could memorialize the human element of war—“the sweat and blood and courage our boys expend every time they face the enemy.” He was rejected for the position, however, possibly because of his age.

Barclay went on to see action in both the Atlantic and the Pacific on various ships, including the USS Arkansas, Pennsylvania, Honolulu, and Maryland, all the while sketching soldiers, sailors, and marines and taking photographs. From late 1942 until June 1943, he mailed many of his pictures to a friend in the United States. In July of that year Barclay, by then a lieutenant commander, was serving aboard the USS LST-342 in operations off Solomon Island when the Japanese submarine Ro-106 torpedoed the tank landing ship. It broke in two, and the aft end sank, taking most of the crew with it, including Barclay, whose body was never recovered.

Lucien Labaudt

Born in Paris in 1880, Lucien Labaudt came to America in his youth and was largely self taught as an artist. In 1910 he settled in San Francisco, where he painted a number of large murals. In the early spring of 1943, he was selected for the War Department Art Program and was assigned to cover U.S. military operations in China, but when Congress canceled the program that summer, Labaudt’s contract, like those of other artists, was picked up by Life magazine. The magazine sent him to India to paint war scenes, and he arrived there in November 1943 after a two-month voyage. The following month Life asked that he travel to China to cover the guerrilla war against the Japanese, which promised to be a rigorous assignment for the 65-year-old artist. Flying from India to China on December 12, 1943, he and 12 others were killed when their American plane crashed at dusk while trying to land in Assam near the Burma border.

Albert Richards

Albert Richards, who was born in 1919 in Liverpool, England, served as a British war artist beginning in December 1943, when he enrolled for six months; he’d previously been called up for war service and had enlisted with the Royal Engineers in 1940. A few months after receiving his commission with the War Artists’ Advisory Committee, he was given the honorary rank of captain. In 1944, after training as a paratrooper, he dropped into Normandy with the 9th Parachute Battalion of the 6th Airborne Division on D-Day near Sword Beach and fought in the Battle of Merville Battery. To record the invasion, Barclay brought along a sketchbook and pencils in his heavy military kit, and he later used his sketches to create a series of fine watercolors, including one depicting the taking of Pegasus Bridge in the early hours of D-Day. Several months later, near the Dutch-German border, he recorded the burial of victims of the massacre at Bande. On March 5, 1945, while still in Belgium, Barclay set off to paint a night attack by the Allies, but his jeep hit a landmine and he was killed. At age 25, he was the youngest of the three official British war artists who were killed in World War II.

Thomas Hennell

Like Eric Ravilious and Albert Richards, Thomas Hennell served in World War II under the auspices of the War Artists’ Advisory Committee, which originally commissioned him to record scenes from the home front. Following Ravilious’s disappearance in Iceland, Hennell was sent there in 1943, but he returned to Britain in mid-1944 to record maritime activity in and around Portsmouth in preparation for the D-Day invasion. After the Normandy landings he was embedded with the Canadian First Army in northern France and subsequently with the Royal Navy, sketching the Allied advance into the Low Countries. With the war in Europe winding down in the spring of 1945, he was sent to Burma to cover the Japanese retreat, and he later traveled to India, Ceylon (Sri Lanka), and Singapore, where he witnessed its capture and surrender. Hennell then went to Indonesia. In November 1945 he was captured on the island of Java by nationalist guerrillas, who presumably killed him.

Gregor Duncan

By the time he was drafted into the Army Air Corps on July 9, 1942, Gregor Duncan had built a successful career in New York City as a cartoonist and illustrator, working for such major publications as Collier’s, Cosmopolitan, the Literary Digest, Reader’s Digest, and the daily newspaper PM. Near the end of 1943, Duncan joined the staff of Stars and Stripes and headed with six other newspapermen to the Mediterranean theater, where he drew comic strips, field studies, maps, and re-creations of battle scenes. In March 1944 he was sent to Naples, Italy, where he met the legendary cartoonist Bill Mauldin. Mauldin quickly took Duncan under his wing, driving him around Naples in his specially assigned Willys Jeep and even taking Duncan to see his wife, a Red Cross volunteer stationed there.

A week later Duncan and another staff sergeant, Jack Raymond, left for the Anzio beachhead to make some sketches. On the way there, near the just-occupied town of Cori, a shell from a German 88 landed in front of their jeep. Raymond was thrown from the vehicle and suffered only minor injuries; Duncan, who was driving, was fatally wounded by shrapnel from the shell. He was 34.

“Gregor Duncan, one of the finest and most promising artists I’ve ever known, was killed at Anzio while making sketches for Stars and Stripes,” Mauldin would write in The Brass Ring, his 1972 memoir. “It’s a pretty tough kick in the stomach when you realize what people like Greg could have done if they had lived. It’s one of the costs of war we don’t often consider.”

Peter Harrington is the curator of the Anne S. K. Brown Military Collection at Brown University.

[hr]

This article appears in the Spring 2020 issue (Vol. 32, No. 3) of MHQ—The Quarterly Journal of Military History with the headline: War List | Fallen Artists

Want to have the lavishly illustrated, premium-quality print edition of MHQ delivered directly to you four times a year? Subscribe now at special savings!