Warships with powerful cannons patrol the waters just off Mobile Bay. It is the summer of 1864, and Union sailors are bristling for a fight, ready to take on any vessel tempted to run the blockade in order to reach one of the last Gulf of Mexico ports still defended by the Confederacy.

Suddenly, the Northern sailors observe an unfamiliar object hovering in the sky above the Alabama coastline. Using whirring airscrews to defy gravity, the bizarre contraption emits a loud noise and belches smoke as it moves slowly toward the Union ships.

The men watch in stunned silence as the monstrous machine slowly drifts in their direction before stopping in midair and dropping a heavy object. The small dark shape falls swiftly, then strikes a Union warship, triggering a huge explosion. Bursting into flames, the vessel quickly sinks.

The Confederate “helicopter” has scored its first victory of the war.

Ancient Inspiration

That scenario is clearly imagined, but it illustrates an incredible case of what-might-have-been history. What if Confederates had invented a helicopter capable of dropping bombs?

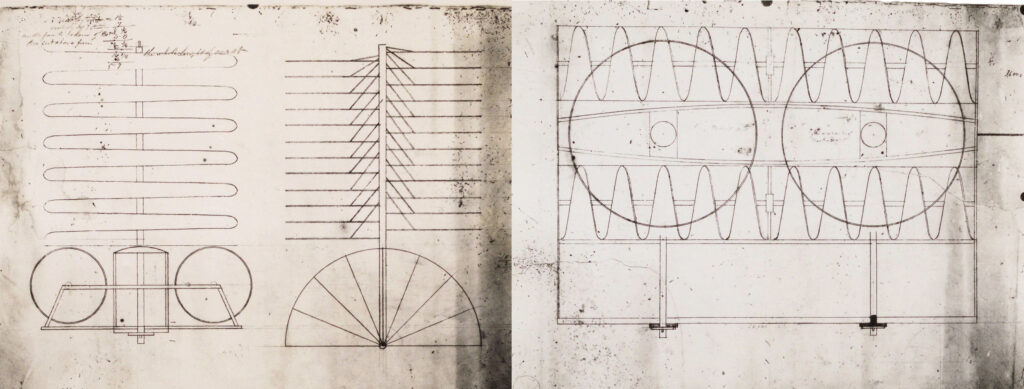

It came closer to happening than many people realize. An innovative inventor in Alabama saw the potential for such an aircraft and actually drew up plans for how it might fly. Those drawings are preserved today in the archives of the National Air and Space Museum at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C.

By January 20, 1862, Union ships had managed to prevent most vessels from entering or leaving the major Confederate port of Mobile Bay. While certainly not a complete cordon, the blockade cut off delivery of supplies and, more important, the export of cotton to other nations—a much-needed source of income for the Southern war effort.

William C. Powers believed he had the answer to breaking the blockade: a motorized airship capable of bombing the Northern fleet. Known today as the Confederate helicopter, his idea offered a revolutionary look at solving a bothersome military problem.

“Mr. Powers sees what’s going on,” said Thomas Paone, museum specialist at the National Air and Space Museum. “The federal blockade is choking off the South. He’s living in Mobile, which is dependent on seaborne trade. He starts thinking, ‘We can’t break the blockade, so what do we do? Let’s try something different.’ That thought process is fascinating to me.”

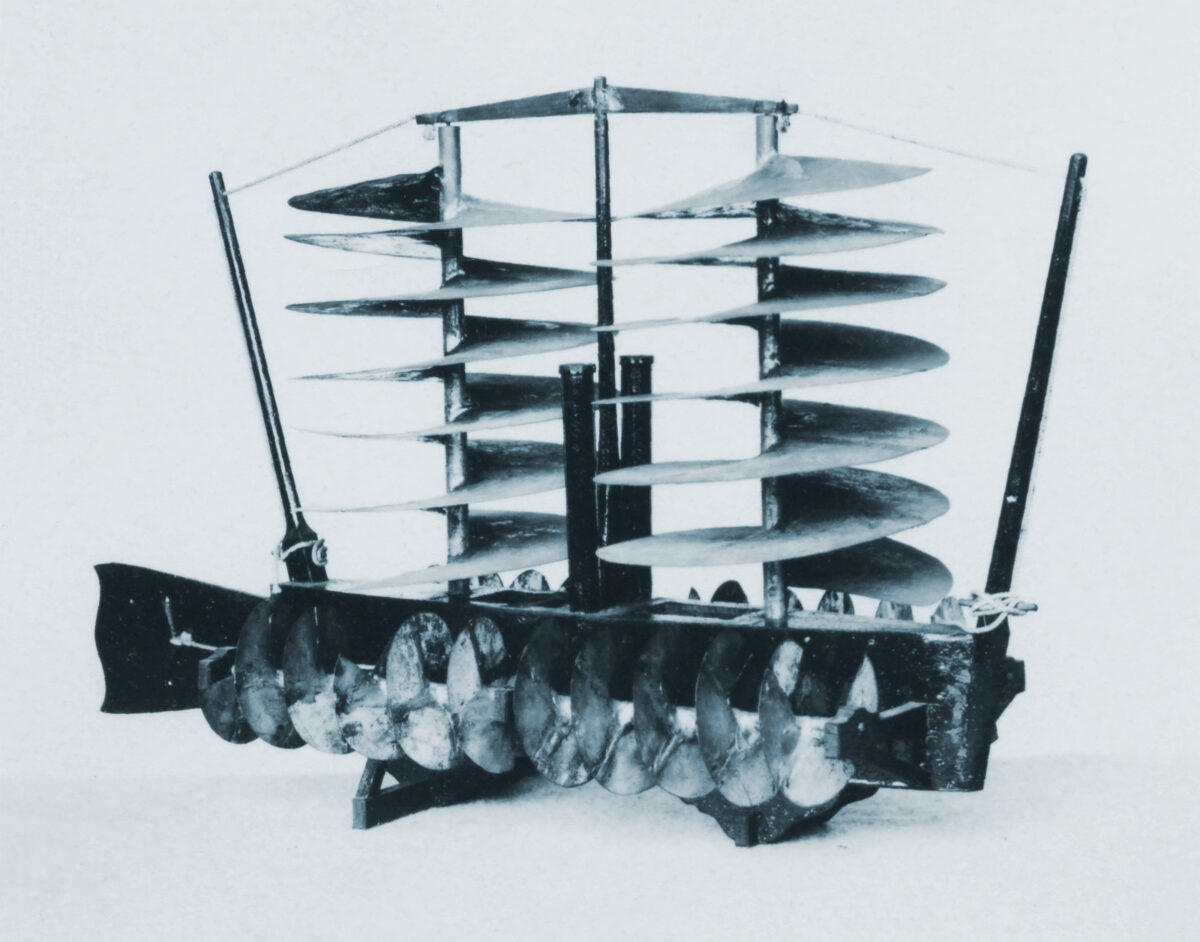

And to many historians as well. Powers’ plans and a small-scale model he built were donated by his family to the Smithsonian Institution in 1941. Since then, researchers and aeronautical engineers have pored over his design to determine the scope and feasibility of his idea.

“Powers realizes this is something that could have a military purpose,” said Roger Connor, curator of the museum’s vertical flight collection. “He was definitely laying the groundwork for something that would fly through the air.”

Powers’ concept is intriguing—especially considering it was devised 40 years before the Wright brothers succeeded in manned powered flight with a fixed-wing aircraft in 1903. He drew upon the ideas of earlier inventors, including ancient Greek mathematician Archimedes and Renaissance artist Leonardo da Vinci.

For propulsion, Powers used the rotational features of the Archimedean screw—originally developed to remove water from the hold of a ship. Da Vinci had also incorporated a version of the invention into his sketches for his helicopter.

But the Confederate chopper was different. Instead of one screw, Powers included three with his design: a single twin-screw system on the top for upward motion and two separate screws on the sides to drive the airship forward. Building something that could fly up and over other things was a dream for many inventors in the 19th century.

“Vertical flight as a concept is more dominant than fixed-wing flight—essentially airplane-style flight—at this time,” Connor said. “Inventors are starting to understand that air acts similarly to fluid. There’s certainly a carryover from nautical construction to the vision for how an aircraft might perform.”

That maritime influence is evident throughout the plans and model. Paone pointed to several aspects of the design that have a distinct nautical style rather than the aviation appearances aviation enthusiasts expect to see today.

“If you look at the drawings of the helicopter, it’s definitely got some ship-building roots,” he said. “It has a ship’s body and smokestacks like a steamer would. It has much more of a feel of a nautical craft than an aircraft.”

Other Flying Machines

Powers’ helicopter came at a time of incredible innovation. Technological improvements exploded from drawing boards as inventors on both sides sought to support the war effort. Mobile was also the home of H.L. Hunley, the first operational submarine to attack a warship in combat. It sank in 1864 shortly after destroying USS Housatonic outside Charleston, S.C.

“Unfortunately, warfare inspires innovation,” Paone said. “In addition to the Hunley, there are all sorts of improvements in the railroad, telegraph, weapons, and ironclads. They come about because of the Civil War and ripple throughout the world stage.”

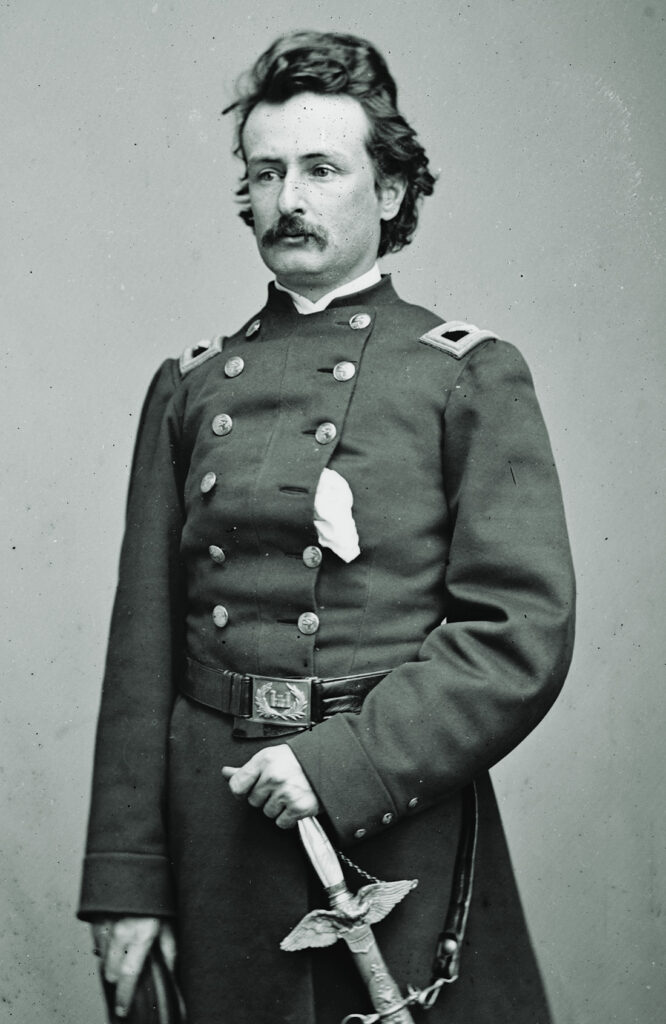

At the time, Powers was not the only one thinking about taking to the air. Edward Serrell, a colonel in the Union Army, also conceived of a flying machine. As chief engineer for the Army of the James, he demonstrated how aerial reconnaissance could be accomplished by using a windup toy that flew upward of 100 feet.

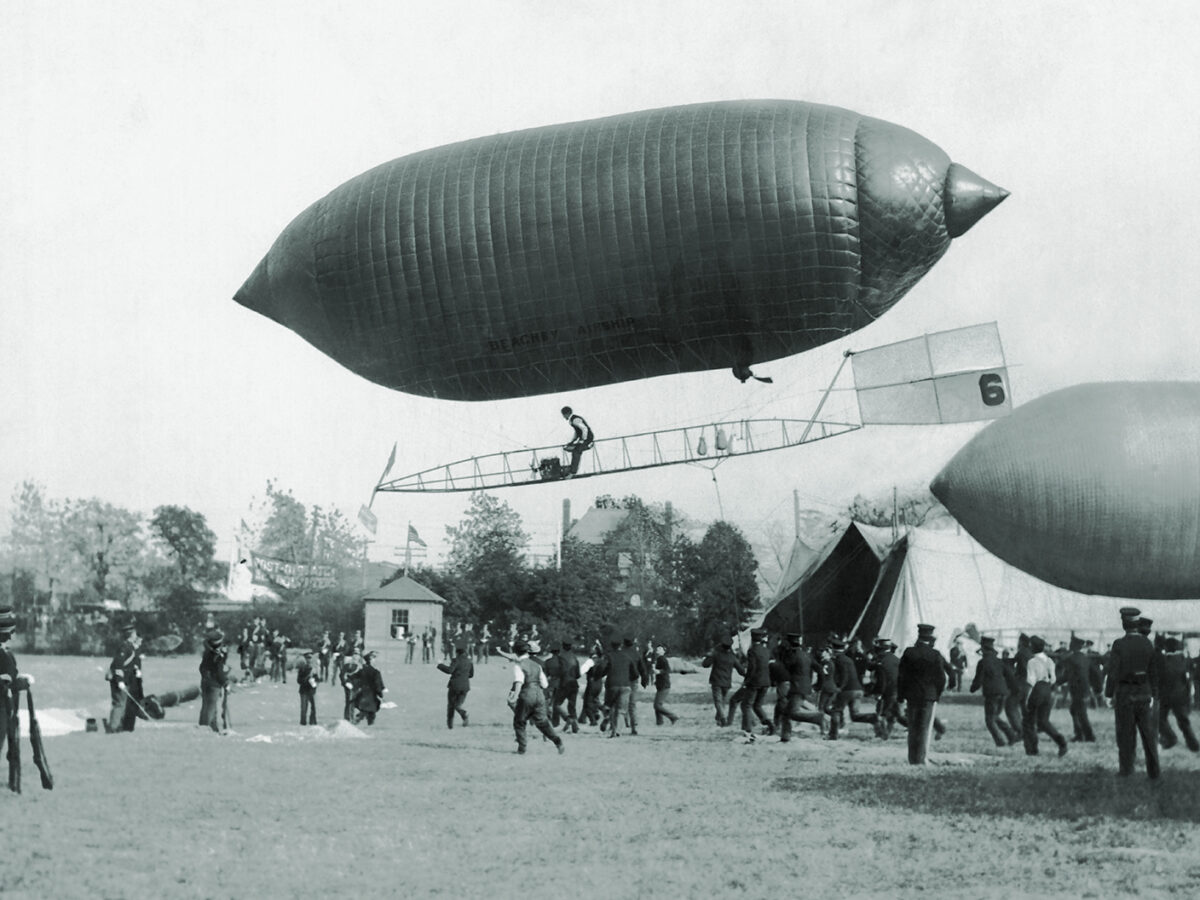

Major General Benjamin Butler liked the idea and ordered Serrell to build a full-sized flying machine. He constructed a 52-foot, cigar-shaped prototype with wings and four fans for lift and propulsion. Called variously the Valomotive and Reconoiterer, the aircraft was waiting for the development of a lightweight steam engine for power when the war ended.

Serrell abandoned his plans with the cessation of hostilities and the whereabouts of his prototype are lost. His papers are conserved in the archives at the National Air and Space Museum. Serrell’s invention is detailed in the book Smithsonian Civil War: Inside the National Collection in a chapter written by Tom Crouch, curator emeritus at the museum.

Amazingly, these were not the only plans in the works for flying machines during the war. Other inventors had conceived of building motor-powered crafts capable of delivering explosive payloads on enemy positions.

Richard Oglesby Davidson of Virginia had his sights set on building an “aerostat,” an aircraft in “the form of an American eagle,” he wrote in his 1840 book on aviation theory. It featured a beak, legs made of spring and feathers painted on the fuselage. The “conductor,” or pilot, sat in a compartment inside the eagle, where he operated the wings for motion. According to the 2016 book Astride Two Worlds: Technology and the American Civil War by Barton C. Hacker, Davidson even considered installing a carbonic acid gas engine for supplemental power.

No one knows today what happened to those plans, though Davidson—who was nicknamed “Bird”—does turn up again during the Civil War. Crouch reports in his chapter in Smithsonian Civil War that the inventor made a tour of the trenches in Petersburg, Va., in 1864, where he showed Confederate troops a wooden model of his concept. He reportedly asked enlisted men to donate $1 and officers $5 so he could construct his flying machine. What happened to those plans—or the donated money—is anybody’s guess.

In 1863, Richmond dentist R. Findlay Hunt proposed building a steam-powered “flying machine intended to be used for war purposes” to Jefferson Davis. The president of the Confederate States of America was so impressed with the idea that he referred Hunt to General Robert E. Lee. After review by his engineers, the concept was deemed unworkable.

After the war, Hunt petitioned the U.S. Patent Office for protection of his design until he could perfect his idea. He purportedly built a model two years later but never applied for a patent.

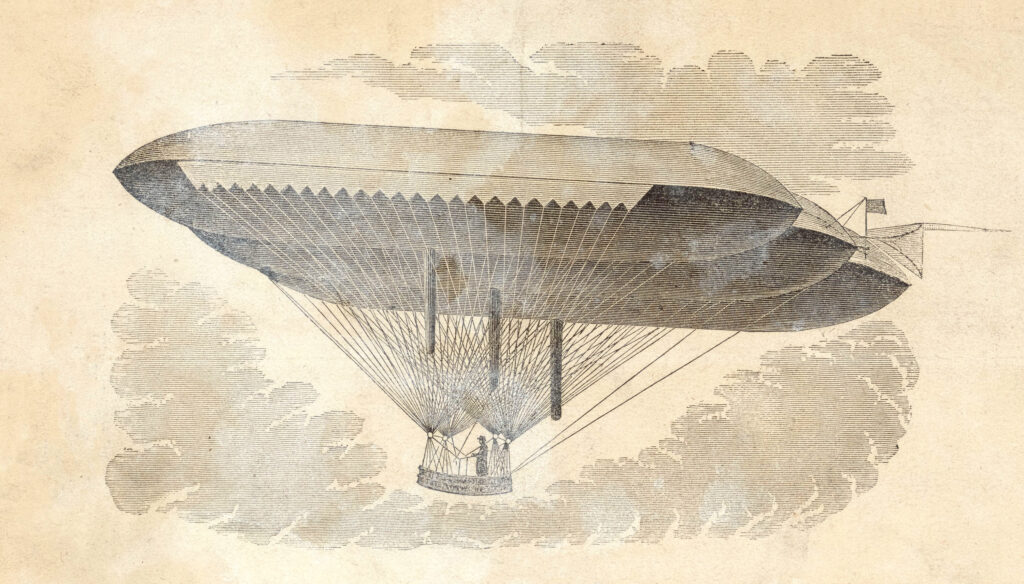

Perhaps the most ambitious plan for an aircraft of war was developed by Solomon Andrews, a New Jersey physician and inventor. He actually built and tested a working model that was flown over Perth Amboy, N.J., in 1863 in an attempt to attract the attention of Union military leaders.

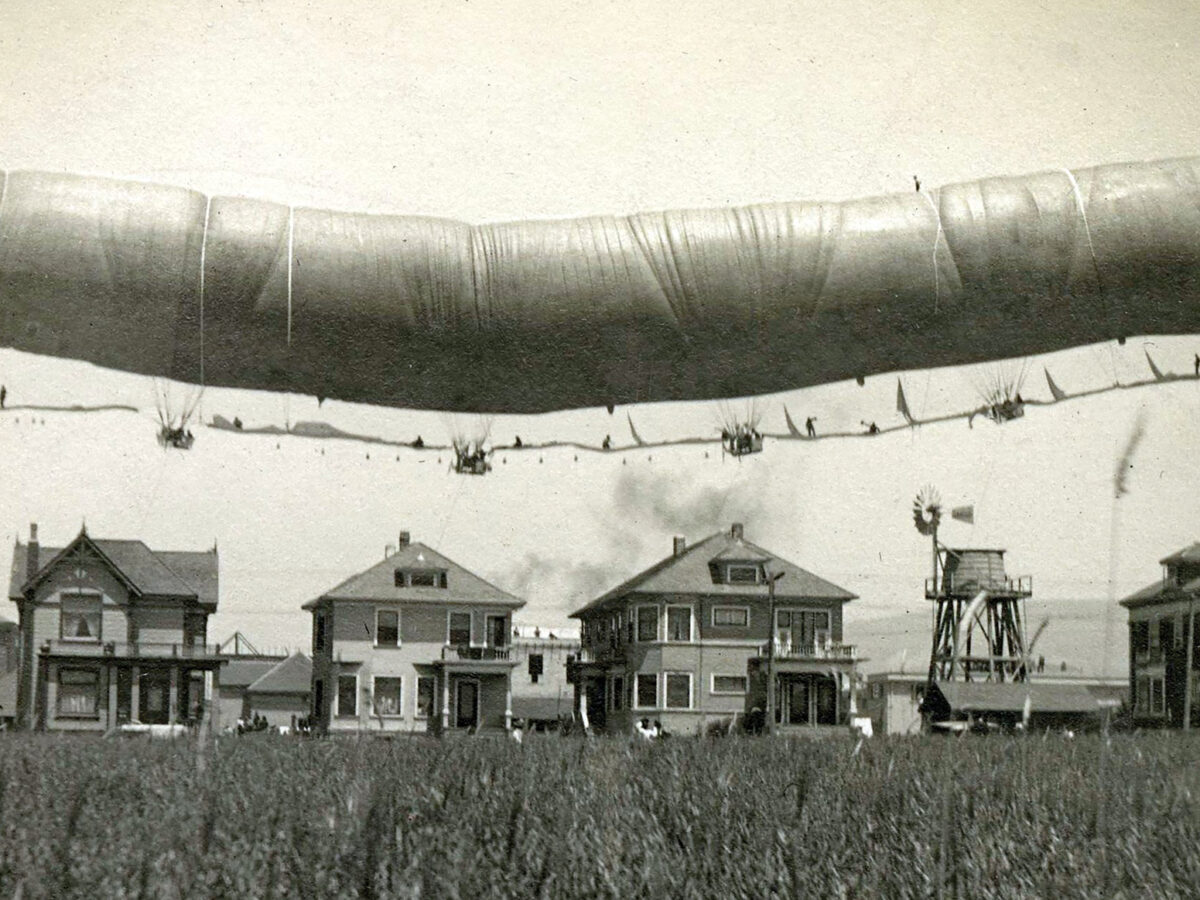

Called Aereon, Andrews’ flying machine was essentially an unpowered dirigible. It consisted of three large balloons tied together with a rudder for steering and gondola for passengers. It had no motor and relied solely on wind for forward movement, though Andrews claimed he could power the aircraft by using “Gravitation,” according to John Toland in the 1972 book Great Dirigibles: Their Triumphs and Disasters.

The balloons were approximately 80 feet in length and 13 feet wide. Each included 21 cells to prevent the gas from sloshing back and forth. In between the balloons and gondola was a 12-foot-long basket that featured a ballast car on tracks. The airship was controlled by moving the basket forward to dive and backward to ascend.

Andrews wrote several letters to President Abraham Lincoln and other officials about his flying machine. He even demonstrated how it would fly using a small model at the Capitol Building and Smithsonian Institution. By that time it was late in the war, however, and Union victory seemed imminent, so Congress opted not to fund the proposal.

Following the war, Andrews formed the Aerial Navigation Company and built a second airship that in 1866 twice flew over New York City. The firm went bankrupt during the postwar economic recession and the Aereon #2 never flew again.

“Ahead of His Time”

While all of the ideas were certainly uplifting, few of them appeared capable of getting off the ground. The dynamics of powered flight in a heavier-than-air vehicle were not well understood in the 1860s and really wouldn’t be deciphered until the Wright brothers took off from Kill Devil Hills in North Carolina at the dawn of the new century.

As for the Confederate helicopter, most aviation experts agree Powers’ design had fundamental flaws that would have prevented it from taking to the air as designed. The airscrews likely would not have generated the necessary lift, while the craft itself was too heavy for the simple steam engine Powers proposed for it.

“The propulsion aspect was not viable,” Connor says. “Powers is not on the leading edge of developing this technology. Others make further inroads than him at the time. However, he is a standout in the concept of application by understanding that it has a military purpose.”

Recommended for you

That’s not to say that Powers wasn’t on the right flight path. Some of his ideas held promise, and one even predicted an innovation that would come about some 80 years later. According to Paone, Powers’ plans called for

lattice-style construction of wood in the aircraft’s fuselage to give it added durability. That concept was used by the British in World War II in the wings of the Vickers Wellington bomber.

“This provides incredible strength without adding lots of weight,” Paone said. “Perhaps Mr. Powers was just ahead of his time.”

Little is known about Powers. According to his family, he was an architectural engineer living in Mobile during the war. When Powers realized the South did not have enough ships to break the Union blockade, he started tinkering with vertical flight. It is believed the Confederate military was aware of his idea but was unwilling to finance something it likely perceived as an out-of-this-world scheme.

Once Powers realized his dream would not become a reality, he hid the plans and model so they would not fall into Northern hands, according to family lore. They remained largely unknown until his granddaughter, Clara McDermott, donated them to the Smithsonian for further study more than 80 years ago.

Since that time, historians and scientists have speculated about what might have been. Had Powers been given the money to test his idea, would he have eventually succeeded? That answer will never be known for certain, but Paone is excited just thinking about what was being dreamt of more than 150 years ago.

“What fascinates me is that you have people who are legitimately looking at pushing the envelope with flight,” he said. “Would this have worked? Probably not, but he’s going down this path thinking maybe he could make something fly.”

Massachusetts-based author Dave Kindy is a self-described history nerd and remembers the centennial celebration of the Civil War. He is a frequent contributor to several HistoryNet publications, as well as Air & Space Quarterly, National Geographic, The Washington Post, The Boston Globe, and Smithsonian.