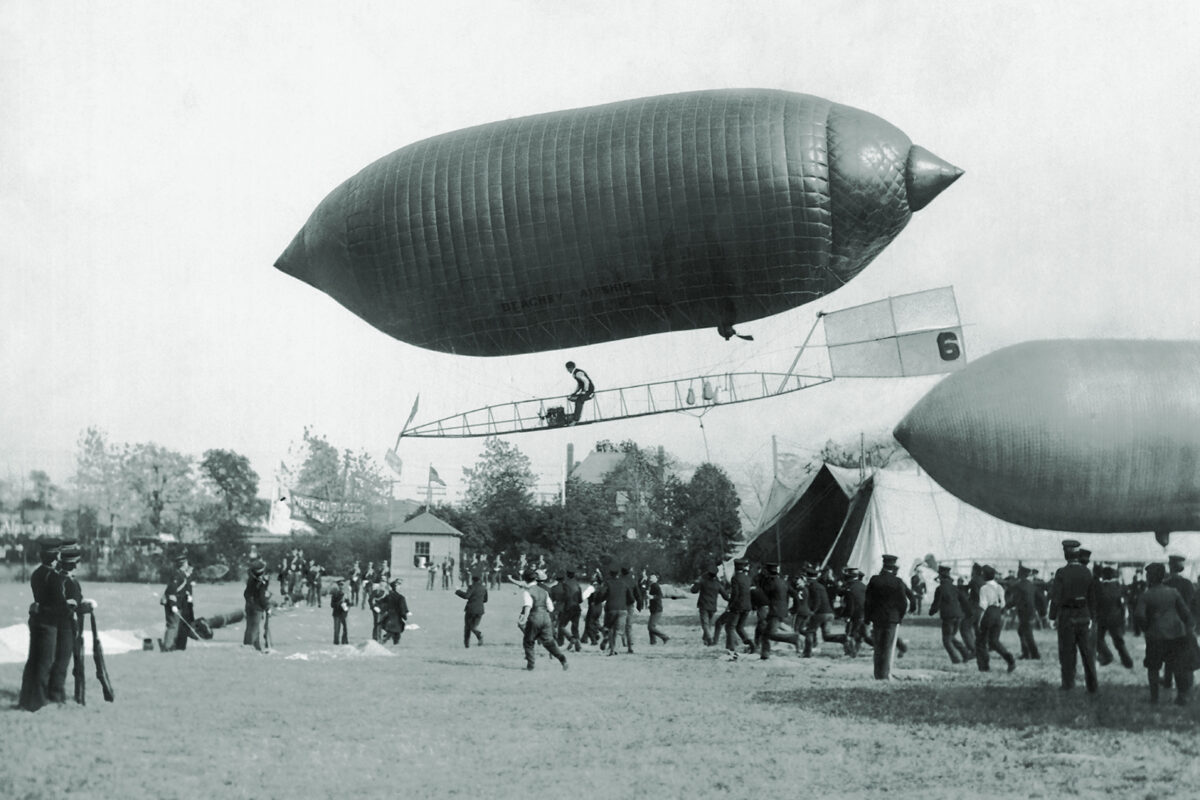

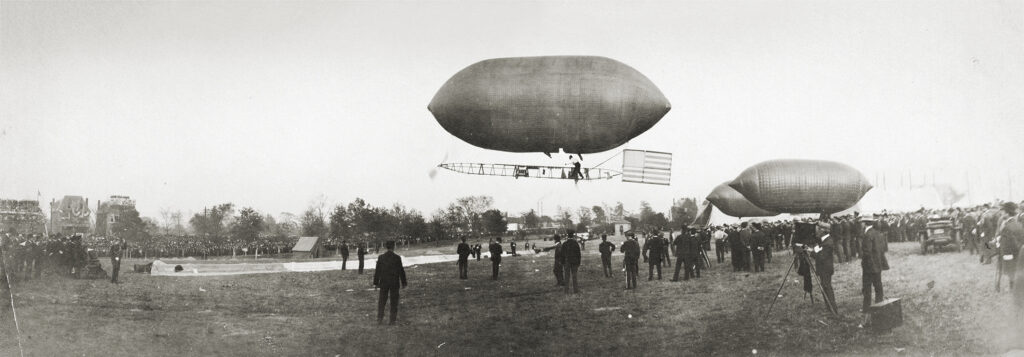

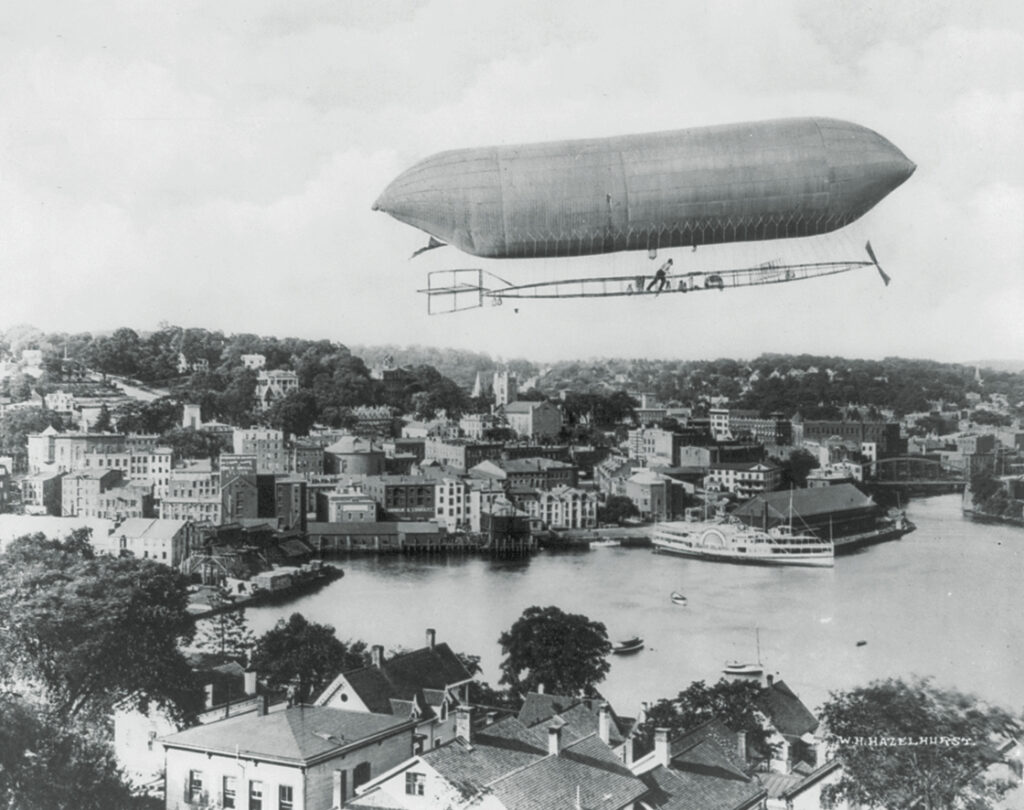

Around 10:30 a.m. on Thursday, June 14, 1906, Washington, D.C., residents spotted an oblong shape floating across the Potomac River toward the city. The thing was immense—62 feet long, 16 feet in diameter—larger than any familiar moving object except a locomotive, with a golden sheen that glowed in the morning sun. A noisy gasoline engine drove a propeller at the nose pulling the object along. A man on a platform hanging from the rig somehow was steering the airborne conveyance.

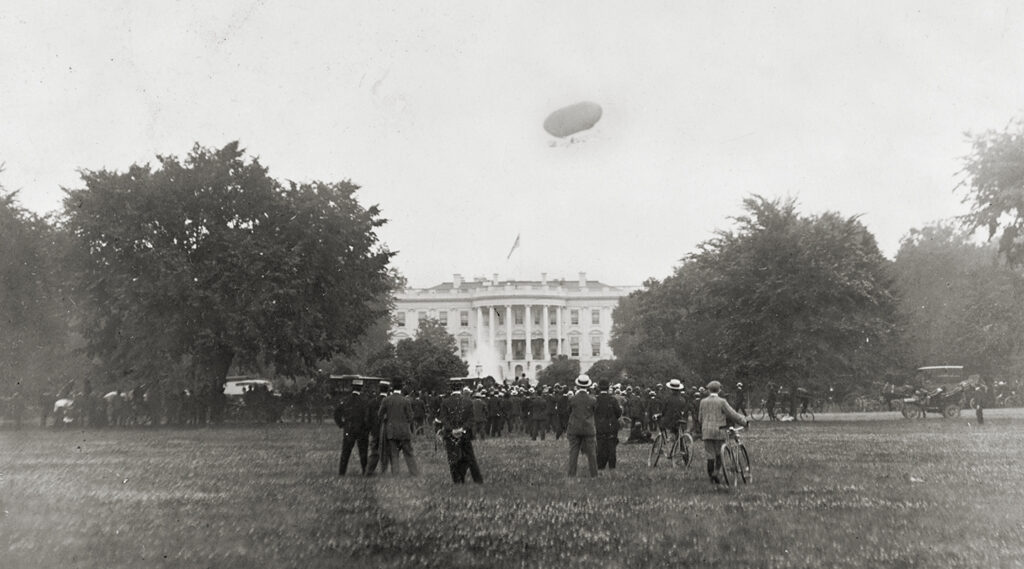

The mysterious craft sailed up the National Mall and landed near the Washington Monument. The occupant stepped off the platform. His name was Lincoln Beachey, he said. He was a dirigible pilot, and he had taken off that morning from a new amusement park in Arlington, Va., where dirigibles were among the attractions. His destination was the White House; he had paused to make a repair. He deliberately lingered on the Monument grounds to let word spread of his airship’s presence. A crowd formed and swelled. Soon, “the drives were lined with grocery wagons, laundry wagons, automobiles, bicycles and other kinds of vehicles and the east side of the Monument was black with a mass of humanity,” The Washington Post reported. Beachey stepped back aboard, fired up the engine, and took off, circling the Monument before heading toward the White House, three blocks north.

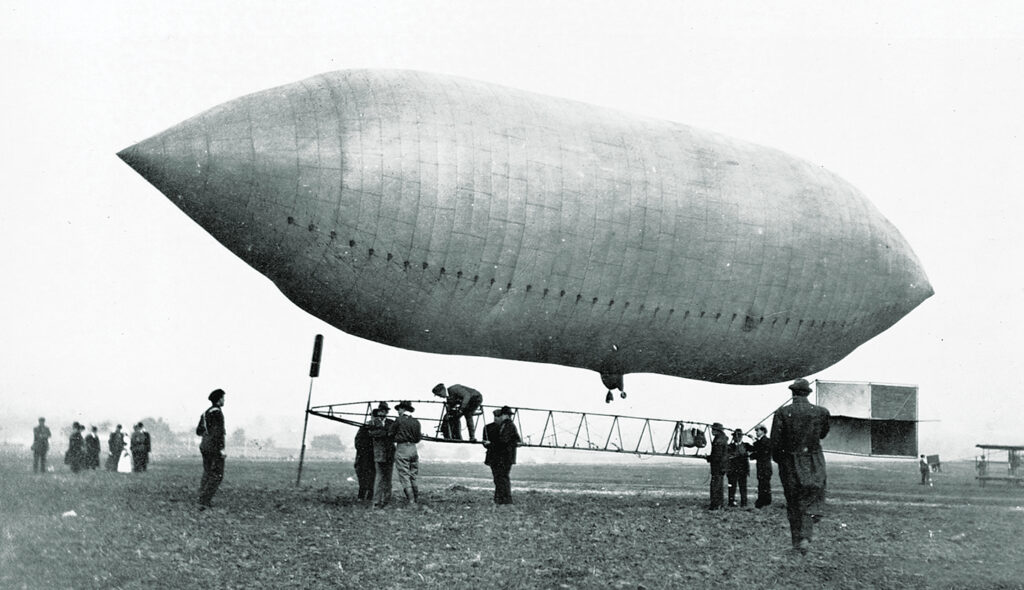

Dirigibles descended from hot-air balloons. Brothers Joseph and Étienne Montgolfier pioneered the first piloted balloon ascent over Paris in 1783. Union and Confederate forces used balloons for reconnaissance and fire control in the 1860s. But these early gasbags had to remain tethered lest the breeze carry them off. Dirigibles, introduced in the late 1600s but not practicable until nearly two centuries later, were rigid, herring-shaped, and self-propelled. To build a dirigible, artisans bolted together a wooden frame, usually of pine or spruce, over which they stretched a thin, tough skin of high-quality Japanese silk, tightly sewn and made airtight with coatings of oil or varnish.

Netting helped maintain the rigid shape. Hydrogen, a gas lighter than air, gave the ungainly airships buoyancy. Operators usually generated their own hydrogen by pouring sulfuric acid over barrels of iron filings and piping the resulting hydrogen into their airships to inflate them. Ropes held the airship in place until an “aeronaut” had mounted a wooden platform slung beneath the craft and tethered by wires and poles of bamboo, wood, or metal. The platform held a gasoline engine that drove a propeller below the aircraft’s nose.

Once untethered and on his way, the pilot controlled his craft—dirigible is derived from the French diriger, meaning “to steer”—using a large wooden rudder aft of the platform, in effect sailing on air. He controlled pitch—the angle of rise or descent—by walking forward and back on the platform. A successful dirigible pilot was hearty, daring, and willing to risk falling out of the sky to his death.

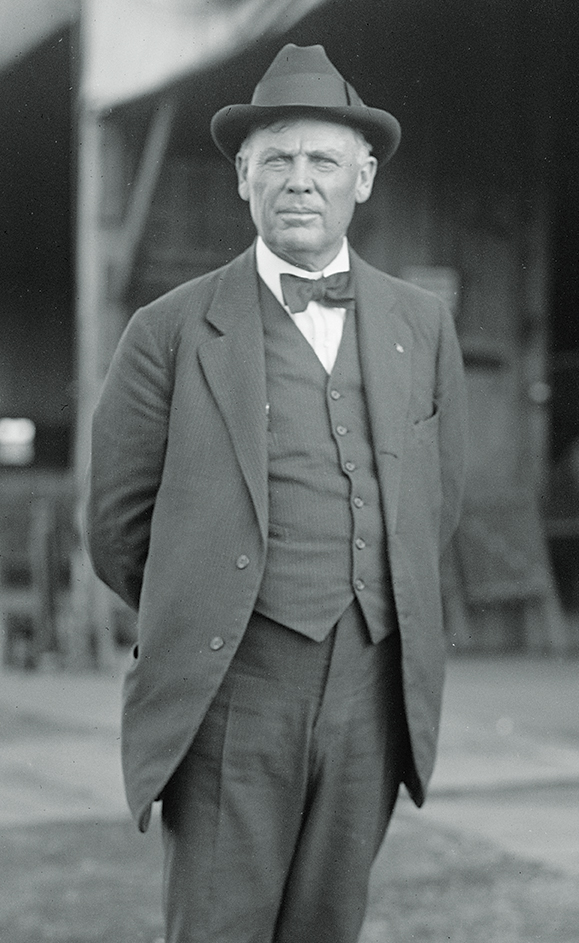

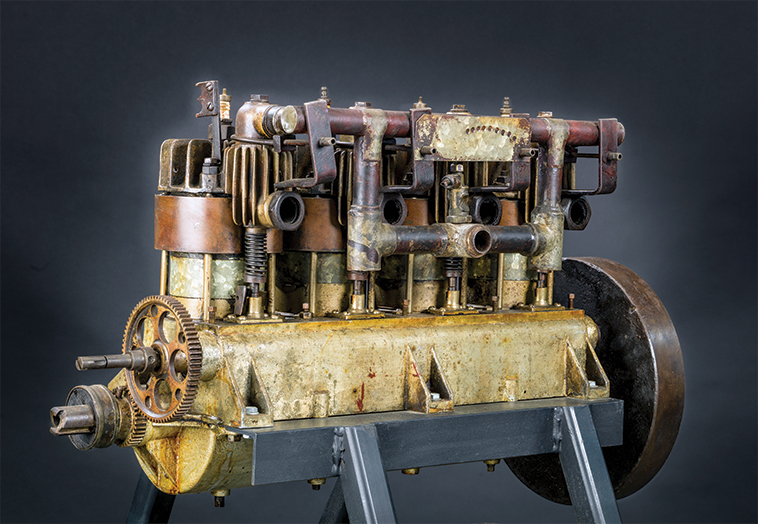

Experimenters worked their way through steam engines—too heavy—and battery-powered electric motors—unreliable—before settling on gasoline-powered internal combustion engines. Brazilian aviation pioneer Alberto Santos-Dumont started building reliable dirigibles in 1898 and in 1901 famously circumnavigated the Eiffel Tower. German inventor Ferdinand von Zeppelin launched a version in 1900. The dirigible entered American popular culture as entertainment. One of the first successful airship builders, Thomas Baldwin, started out at 21 as a circus acrobat and trapeze performer. Bitten by the urge to fly, he got onto the county-fair circuit piloting hot-air balloons and in 1885 became the first American to parachute from a balloon gondola.

Designating himself “Captain Tom,” Baldwin began building dirigibles at his shop in San Francisco in 1903. Available engines proved too weak. In 1904, an unfamiliar make of motorcycle zipped past his shop. Baldwin investigated and learned that the two-wheeler ran on a powerful but lightweight four-cylinder gas engine built by Glenn Curtiss of Hammondsport, N.Y. Baldwin ordered a Curtiss engine by telegraph, mounted it on his airship, rigged a drive train to a propeller, and took to the air.

Dirigible operators transported their craft by rail, for each appearance breaking down and rebuilding the entire assembly to fit into a boxcar. Bookings focused on fairs, expositions, and amusement parks—settings that drew sizable crowds over several days, weeks, even months. In October 1904, Baldwin took his Curtiss-powered dirigible, California Arrow, to the Louisiana Purchase Exposition in St. Louis. Finding himself too heavy for his airship, he deputized skinny employee Roy Knabenshue, an experienced balloonist, to take it up. Navigating in lazy circles over the fairgrounds, Knabenshue astonished onlookers and landed safely. California Arrow was the first successful dirigible in the United States.

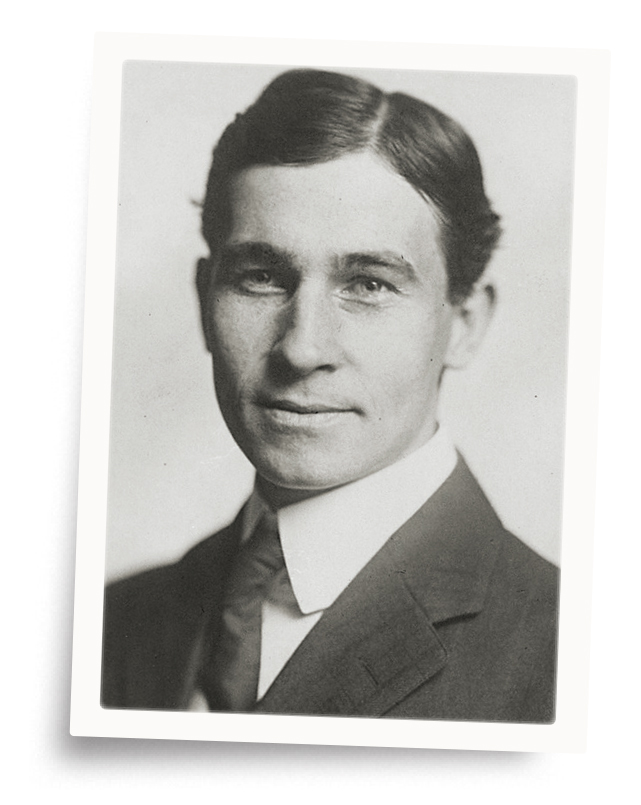

Baldwin set about building a fleet of dirigibles using five-horsepower Curtiss engines. He was hunting for additional hands when a youth came by in March 1905 seeking work. Growing up nearby in San Francisco, 18-year-old Lincoln Beachey had raced bicycles and motorcycles, in the process becoming an adept mechanic. Baldwin put Beachey on his ground crew. In 1905 Roy Knabenshue went home to Toledo, Ohio, to build his own dirigibles. That August, aboard Toledo II, Knabenshue departed New York’s Central Park and soared above Manhattan’s skyscrapers, putting dirigible flying on the map.

Knabenshue’s exit left Baldwin short a pilot. Beachey, compact, athletic and eager, fit the bill. He proved deft at piloting airships at county fairs and other events but, itching for more pay than Baldwin was offering, joined Knabenshue. The two worked the seasonal exhibition circuit. In June 1906, they contracted to fly at Luna Park, a new amusement park in Cleveland. One show Beachey was at 500 feet when two bamboo platform spars failed. The pilot’s platform buckled, shoving the propeller into and through the airship’s skin. The deflating dirigible dropped slowly. Beachey, woozy from inhaling hydrogen, hung on until he was about 20 feet from the ground and jumped, hitting the dirt unconscious but quickly reviving.

The Cleveland operation was part of a growing chain. Knabenshue landed a contract with a new branch in Arlington, Va., across the Potomac from the nation’s capital. “The new Coney Island,” as Washingtonians were already calling their Luna Park franchise, featured a roller coaster, a ballroom, a theater, restaurants, and an arena big enough to accommodate elephant shows and circuses. Besides its bill of concerts, dances, and extravaganzas, the park quickly became a popular setting for company picnics and amateur athletic events. An advertisement in the June 7, 1906, Washington Post urged readers to “KEEP YOUR EYE ON KNABENSHUE’S AIRSHIP June 12 to 18.” As part of his ballyhoo, the aviator told reporters he might just fly across the Potomac, land on the White House roof, and deliver a message to President Theodore Roosevelt. People scoffed. No airship had ever flown into Washington, D.C.

Beachey lobbied to make the trans-Potomac flight. He had proven a capable, daring stunt flyer and coverage of his recent misadventure in Cleveland had lent his name notoriety. If Beachey came to grief, Knabenshue reasoned, he could blame pilot error. If Beachey succeeded, their Luna Park stand stood to sell out. Knabenshue told his protégé yes and boarded a train to appear in Buffalo, where he flew in another dirigible and wound up in Lake Erie but was fished out unhurt. On June 14, Beachey inflated his airship, performed his pre-flight check, revved the Curtiss craft, and, just after 10:00 a.m., took off.

After his theatrical pause at the Washington Monument, Beachey landed at the south edge of the executive mansion’s lawn. Another crowd gathered. Gawkers jumped the low picket fence that constituted the security perimeter. President Roosevelt was two miles away, giving the annual commencement address at Georgetown University (“Don’t flinch, don’t foul and hit the line hard,” he was exhorting the graduates about the time Beachey came calling). First Lady Edith Roosevelt emerged, chatted with the pilot, and examined his dirigible. “That fellow is only seeking an advertisement,” Presidential secretary William Loeb, irked by the spectacle of an airship drawing a crowd so close to the White House, told an assistant. “He has no invitation or permit to come here.” Police shooed onlookers and told Beachey to take off. He insisted on giving Loeb a letter for the president. The message is lost to history; Loeb may have thrown it away.

Beachey took off, banking east over the Treasury Building and following Pennsylvania Avenue NW toward the Capitol. He kept his altitude low, 150 to 500 feet, to give spectators a good look. “Business in Washington was practically at a standstill,” a newspaper reported. “The streets were filled with people, the roofs of houses were covered with them and heads were protruding from every available window, all craning their necks upward to get a glimpse of the aeronaut.”

The unfamiliar sound of an engine putt-putting in mid-air and the sight of a dirigible closing on the Capitol disrupted congressional deliberations. A stampede of senators, representatives and civil servants piled outside to watch the contraption land near the Capitol’s east steps. “I guess I am about the only private individual who has ever stopped Congressional legislation,” Beachey quipped later.

Newsmen and Washingtonians of all sorts came to gape as Beachey held forth. The flight would open a new era in aerial history, he predicted. Beachey asked for volunteers to hold his machine in place and, fuel can in hand, went for gasoline. Returning, he gassed up, bounded onto the airship’s catwalk, and started the engine. Taking off, he circled the Capitol dome and flew back to Luna Park. The calm, capable “Boy Aeronaut” became an instant celebrity. The dirigible landing was the talk of the capital. “White House and Capitol Upset by an Airship,” a headline read. “Sky Pilot Soars Over City, Thousands Staring,” blared another. Witnesses took to wearing typewritten labels on their lapels that read “I Saw It!”

Beachey took fame in stride. “It was the easiest flight I have ever made,” he told reporters. “The air was just calm enough, the sights were beautiful, and everyone I saw had on a pleasant smile and a mouthful of cheers. Washington looks like a huge flower garden full of block houses and bugs as seen from the sky. The question of navigating is no longer an experiment. I can go to breakfast in my airship.”

Beachey performed for overflow crowds for the rest of the engagement at Luna Park. He soon went solo, setting records for speed and maneuvers. Winning races and mastering stunts, Beachey was soon recognized as America’s best dirigible flyer. In June 1907, he took off from seaside Revere, Mass., flew into Boston, and landed on Boston Common to cheers. Airborne again, he circled the State House’s golden dome. Over Massachusetts Bay his engine quit; fishermen rushed to his rescue and towed his craft to shore. “The distance from the earth did not cause me the least worry,” he said. “It is a hard place to adjust a cranky motor.”

Later that month, he performed at newly opened Happyland Amusement Park on Staten Island, N.Y. To promote his show, he bombarded Fort Wadsworth, nearby on Staten Island, with balls filled with passes to the park. He flew over Brooklyn, then Manhattan, landing at Battery Park. As usual, a crowd materialized. Police dispersed the onlookers and ordered Beachey to fly off. He vowed to land atop the 20-story Flatiron Building, but a propeller malfunction and uncooperative gusts dumped him into the East River. Boaters fetched him and his aircraft. Soon Beachey was back at Luna Park in Arlington. At the Washington Post’s behest, he flew to the capital, dropped passes to the Jamestown Tercentennial Exposition in Norfolk, Va., again circled the Washington Monument, landed near the Post building, and returned to Luna Park.

“There’s really nothing to it,” he told a newsman. “It’s just the same as being on the ground so far as nervousness is concerned. I stand on this two-inch [thick] beam along the underside of the framework…and think nothing whatever about being 2,000 feet in the air. It’s just as safe up there as it is down here if you don’t get scared, and scared people have no business in an airship.” Beachey stuck with dirigibles until he worked an air meet in Los Angeles in 1910. Among the aircraft on hand was a fixed-wing biplane. “Boy, our racket is dead!” he told a pal.

He was right. In 1903, brothers Orville and Wilbur Wright had gotten a fixed-wing aircraft aloft and soon went into biplane production. Mechanical genius Glenn Curtiss was installing his motorcycle and dirigible engines into biplanes he designed and built. On July 4, 1908, Curtiss made the first public flight sanctioned by a professional association. Two years later, he pioneered a flight from Albany to New York City. The Wrights sued, claiming he was infringing on their patent.

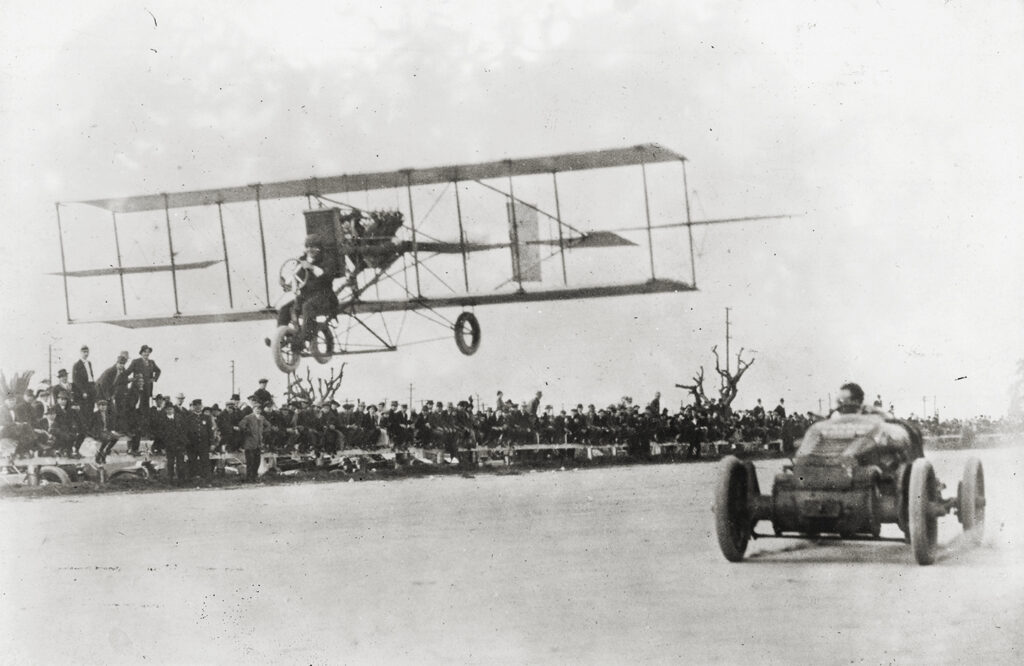

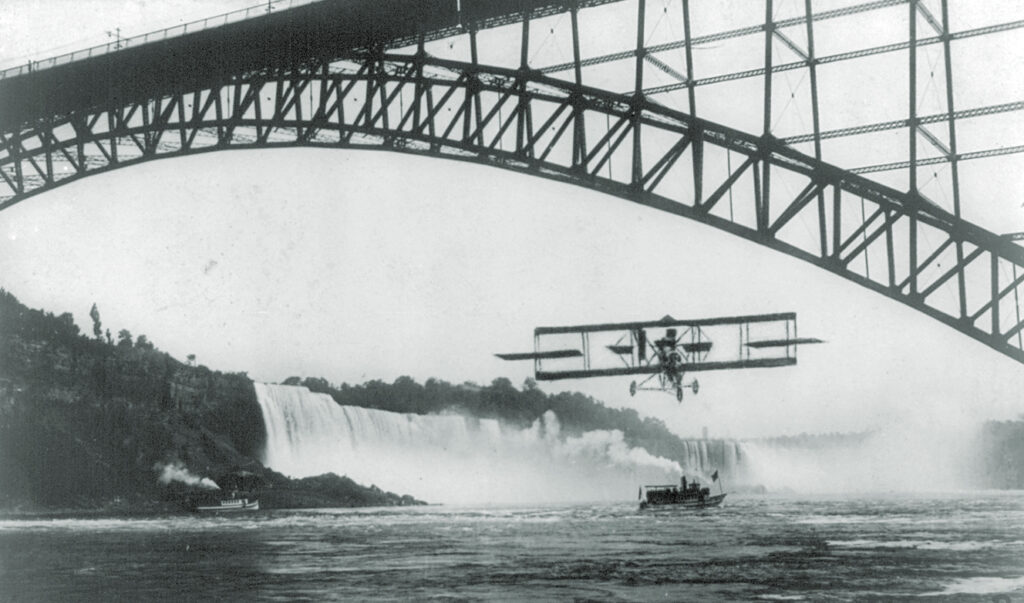

Curtiss, determined to prove that his airplanes stood apart from and surpassed the Wrights and other competitors, started the Curtiss Exhibition Team, in 1911 hiring the nation’s leading aeronaut, Lincoln Beachey. Beachey cracked up his first Curtiss biplane, but quickly mastered the machine. He set speed records, was the first American to loop the loop, and flew upside down. After a flight over Niagara Falls, he swooped back under the bridge across the river. He learned to combine fast climbs followed by vertical plunges that he called “Death Dips,” pulling up at the last second. He partnered on tour with famed race-car driver Barney Oldfield, flying low over Oldfield’s head as the racer steered around dirt tracks, sometimes nudging Oldfield’s hat off with a tire. At Yale University, he dropped baseballs from his plane while the Yale catcher tried to snag them. Other flyers attempted to copy Beachey’s moves but none came close and a few crashed trying. “Beachey is the most wonderful flyer I ever saw,” Wilbur Wright said.

In May 1911, back in Washington, D.C., flying a Curtiss plane in an aerial competition at Benning Race Track, Beachey left the pack to head downtown. He circled the Capitol dome, then flew over the city in swirling winds. “Five years ago, I satisfied a strong desire to circle the Capitol in a dirigible and since that time I have always wanted to do so in an aeroplane,” he told newsmen afterward. “The Capitol loomed in the distance and I could not withstand the temptation.”

Beachey was back again in September 1914, this time announcing his flight beforehand. He circled the Capitol, looped the loop three times, flew upside down, and sailed over the White House as president Woodrow Wilson watched from an upstairs window. His purpose, Beachey said, was “to bring America first in things aeronautic” and demonstrate airplanes’ military potential. The event’s excitement was marred slightly by what may have been the first mid-air collision: his plane struck and killed a carrier pigeon.

Beachey’s luck ran out on March 14, 1915. He had parted with Curtiss, put biplanes behind, and was flying a flashy single-wing aircraft of his own design. At a San Francisco airshow, after looping and flying upside down at high speed, he dove sharply, eliciting cheers and gasps that turned into screams when his aircraft’s wings broke off and his plane plunged into San Francisco Bay. “The Daredevil of the Air” was dead at 28.

Curtiss had won a contract to build planes for the U.S. Navy; the Wrights and others were building planes for the Army. World War I accelerated aircraft development, including the use of dirigibles and planes to drop bombs. In Washington, the capital’s vulnerability from the air became clear. The city no longer welcomed airborne daredevils and, over the years, layers of municipal and federal regulation restricted and controlled the capital airspace. After the 9/11 terrorist attacks, a “flight restricted zone” excluded aircraft lacking Federal Aviation Administration authorization from entering DC’s airspace. Anyone trying to fly an aircraft to the White House would be chased by military jets or downed by anti-aircraft fire—a far cry from that tranquil day in 1906 when Lincoln Beachey alighted in the White House yard.

Dr. Bruce W. Dearstyne is a historian in Albany, N.Y. SUNY Press published the second edition of his book The Spirit of New York: Defining Events in the Empire State’s History which includes a chapter on Glenn Curtiss, and his newest book, The Crucible of Public Policy: New York Courts in the Progressive Era, in 2022.

This story appeared in the 2023 Autumn issue of American History magazine.

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.