Was San Francisco’s John Morrell a stock-swindling grifter or a deluded visionary? In 1906, Morrell, president of a business venture he called the National Airship Company, announced plans to build a fleet of airships to link America’s cities. It was an enticing dream: dirigibles, nearly a quarter of a mile long, that could cross the country in a day or reach London in 24 hours. A San Francisco businessman could fly to New York for lunch and be back home in time for bed. The railroads were dead, Morrell promised. Air travel was the future.

Although Morrell’s vision outpaced early 20th-century technology, he attracted numerous investors in San Francisco. After all, this was the hometown of August Greth and Thomas Baldwin, the innovators behind America’s first dirigibles. Greth had taken his California Eagle aloft in October 1903; Baldwin had flown his California Arrow the following August. Perhaps Morrell could build on their success.

In August 1907, Morrell unveiled his first airship. Named Ariel, it was 600 feet long and driven by five automobile engines. Before the maiden flight, an October gale snapped the balloon’s tether lines and drove it across San Francisco Bay. The trees of Fair Oaks, California, shredded the fragile fabric and destroyed the airship.

Dismayed but undefeated, Morrell started work on a replacement. At the same time, the National Airship Company opened a sales office in Portland, Oregon. Advertisements in the Oregon Daily Journal announced that the company planned to have its new dirigible in service by April 1, 1908. The airship would fly the San Francisco to Portland route, carrying 100 passengers and 30 tons of mail. Investors purchasing stock at the bargain rate of ten cents a share could expect exponential returns.

The company’s ambitious claims attracted the interest of the federal government, and the U.S. Post Office opened an investigation into whether Morrell’s activities constituted mail fraud. Meanwhile, a disgruntled investor named S.L. Jacobs filed a complaint against Morrell in San Francisco Police Court, claiming that he had violated section 564 of the California Penal Code—making false statements about his company to investors. Morrell was arrested and released on bail while awaiting a trial.

Morrell realized that he required a working dirigible to establish his legitimacy. Hoping for a quick result, he scaled back his ambitious plans. The new airship would be smaller, only 450 feet long and 60 feet in diameter. It would serve as a proof of concept and a training vessel, a preparatory step toward a 1,250-foot behemoth that Morrell envisioned.

As the airship neared completion, Colonel Fedor Postnikov, a former Russian army balloonist, expressed concerns about the quality of Morrell’s materials. The envelope, made of light canvas coated with varnish, might have been sufficient for a small balloon, Postnikov informed reporters, but the fabric was unlikely to resist the pressures found in a larger airship. Morrell dismissed Postnikov’s qualms: he said his envelope employed a secret varnish that made it stronger than it appeared. The airship would be fine.

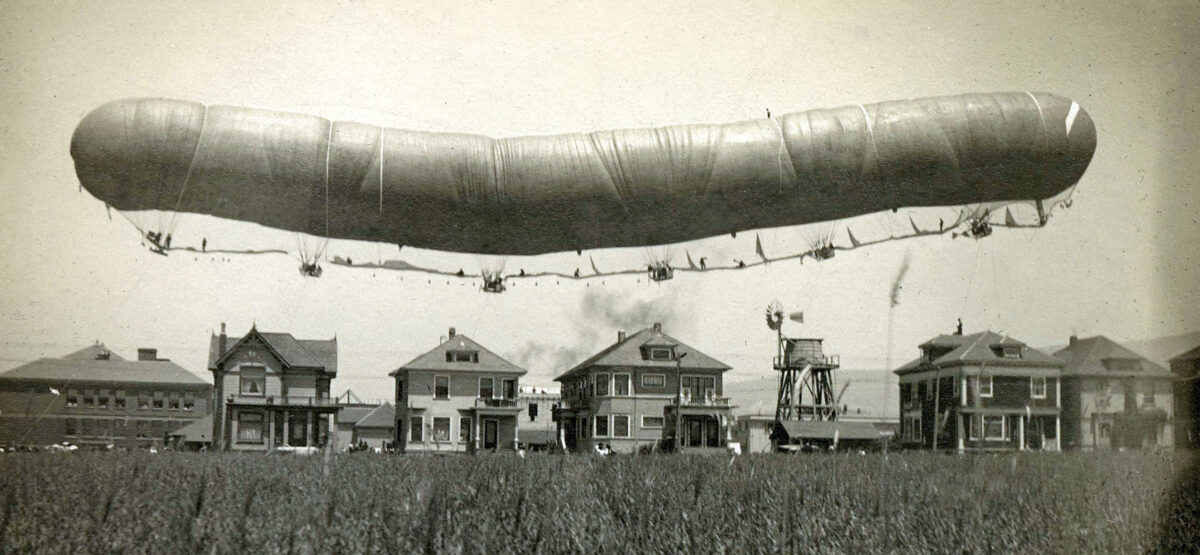

San Francisco refused permission for a second launch, so Morrell relocated to nearby Berkeley. He tried to keep his official launch date a secret, but the news leaked. On May 23, 1908, thousands of people arrived to watch the first flight. The balloon, a bulging, misshapen sack filled with 500,000 cubic feet of hydrogen-based illuminating gas, strained against its tether lines. The official crew consisted of fourteen men and two photographers. Morrell spent the final minutes before launch evicting adventurers who had stowed away in the netting beneath the airship.

Shortly before noon Morrell ordered the tether lines slackened. His crew started the ship’s five engines. As the dirigible rose, the envelope appeared to be unevenly inflated. The rear end of the envelope was fine, a taut, smoothly stretched surface. The bow, however, seemed underinflated, a section of limp, wrinkled fabric. Morrell was unconcerned, believing the pressure would equalize along the length of the airship. He ordered the flight to proceed.

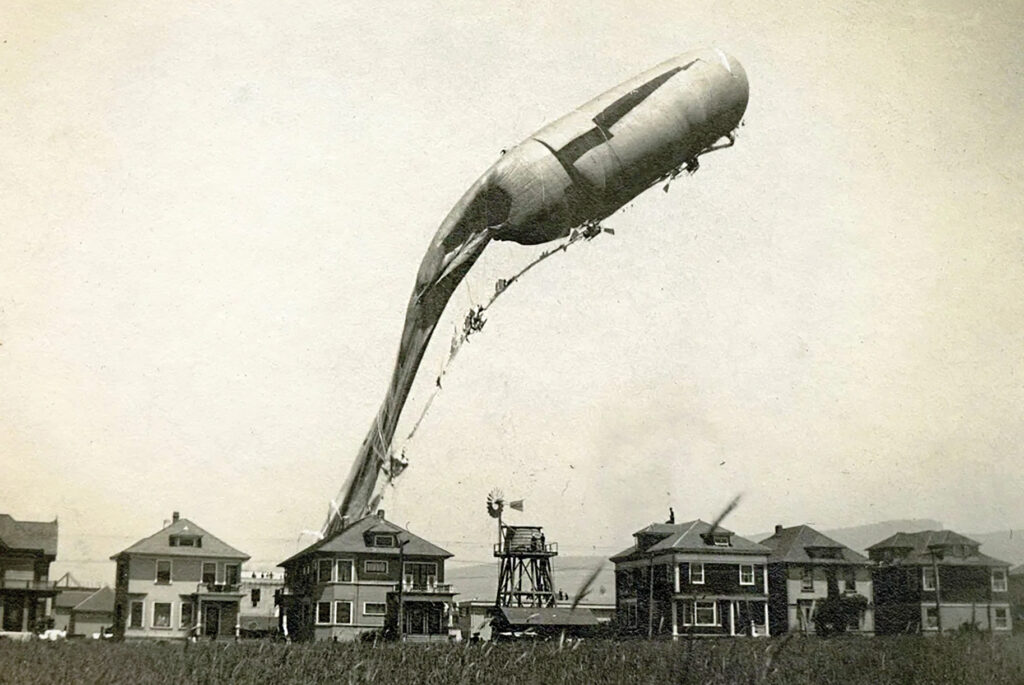

The balloon climbed to 150 feet. As it ascended, its longitudinal disparity worsened. The weight of the forward engine, which was inadequately supported by the underinflated section of the balloon, dragged the nose down. As the tilt increased, the trapped gas rushed aft, exacerbating the problem. Morrell shouted orders to his crew in a vain attempt to level the unbalanced airship, but it was too late. The ship pitched forward and entered a shallow dive.

The stressed fabric burst with a loud crack. Stitches unraveled along a weak seam and pressurized gas poured through the tear. The dirigible accelerated toward the ground. The crowd screamed; panicked onlookers fled the impact zone. “Down plunged the airship,” wrote the San Francisco Call. “It heaved from side to side, like some wild monster, attempting to shake off the desperate, clinging forms, hanging like spiders from its sides.”

Some of the crew jumped clear as the dirigible’s nose plowed into the ground. Others were buried beneath torn canvas, sundered nets and snapped steel tubing. Rescuers emerged from the frightened crowd and tore the balloon with knives to free the trapped men. Injuries ranged from broken bones to internal injuries and concussions. A propeller struck Morrell, cutting him and breaking both of his legs.

The dirigible was destroyed, but, miraculously, no one died in the crash even though most of the crew ended up in the hospital. In the days that followed the accident, souvenir hunters looted the wreckage. By the time Morrell left the hospital, little remained of his dream.

Morrell blamed the accident on his investors—their lawsuits had forced the accelerated pace of development, he said, leading to a flawed product. Nevertheless, he had produced a dirigible, delivering a version of what his stock prospectus had promised.

He vowed to try again, promising to build a bigger and better airship, but legal difficulties occupied his attention for the next year. The Berkeley police department forbade further flights in the city, and, although he managed to convince the courts of his legitimacy, he never built another airship. The age of the airplane had arrived in California, but it would still be decades before transcontinental jets—not leviathan dirigibles—whisked San Francisco businessmen to New York for lunch.