Wilbur and Orville Wright were entrepreneurs in every sense of the word. They invented the world’s first successful flying machine and planned to build it in quantity, promote and sell it. They organized a company, assumed the risks, applied for patents to protect their creation and sought sales contracts. They succeeded far beyond their wildest dreams. But they had to leave their homeland and travel to Europe to prove what they had done.

During the years after their first successful flights at Kitty Hawk, N.C., in 1903, they improved their Flyer and made many test flights at Huffman Prairie near Dayton, Ohio. With a patent pending, they were afraid their invention would be copied while they carried on negotiations to find buyers. After their last flights in 1905, they stored the Flyer and did not take to the air again for the next 2 1/2 years. During that time, they were constantly defending against the disbelievers their claim of having flown. When they wrote a letter to Scientific American magazine telling what they had done, the editor published a cynical editorial in the January 13, 1906, edition headlined ‘The Wright Airplane and Its Fabled Performances.’ The editor called for the names of witnesses to their flights, which the Wrights promptly furnished. Letters were then sent to 17 onlookers, who confirmed that they had indeed seen the Wrights fly. The magazine stated in its December 15, 1906, issue that ‘in all the history of invention, there is probably no parallel to the unostentatious manner in which the brothers of Dayton, Ohio, ushered into the world their epoch-making invention of the first successful aeroplane flying machine.’ And still there was widespread public disbelief.

The Scientific American episode was typical of what the brothers experienced as they tried to market their invention. They attempted to interest the U.S. government in ‘the production of a flying machine of a type fitted for use’ but were turned down–not once but twice. Although they received a U.S. patent on May 22, 1906, they were reluctant to furnish drawings or data to individuals for fear they would lose control of their own invention.

There seemed to be no viable interest in purchasing the Flyer in the United States, so they wrote to a number of government officials in Europe, then decided they should make a trip to meet potential deal-makers in England, France and Germany and demonstrate the latest version of their flying machine. Wilbur traveled to England and France in May 1907 and was joined in July by Orville and later by Charles E. Taylor, their mechanic. The latest version of the plane was shipped to Le Havre in anticipation of demonstrations, and a series of talks began with European agents, discussions that the Wrights hoped would lead to a sales commitment. But negotiations soon collapsed, as would-be European competitors were by then building and flying their own machines. The Continental aviators received so much public acclaim for their short flights that the Wrights seemed likely to lose the recognition they deserved for being first to fly. The Wright brothers did, however, sign an agreement with Flint & Co. and Hart O. Berg, an American engineer, to act as sole agents for the the brothers’ abroad and to negotiate agreements with governments for purchase or use of Wright machines and formation of companies to take over ownership or exploitation of the brothers’ inventions.

They returned home in the fall of 1907, disappointed in developments on the Continent but determined to continue their work. They built new, improved aircraft, conducted experiments with hydroplanes and floats and also tested a new engine. Despite the apparent put-down in Europe, 1907 proved to be a turning point for the Wrights in America. On August 1 the War Department established an Aeronautical Division within the U.S. Army Signal Corps for the study of the flying machine and the possibility of adapting it to military purpose.’ In December the Signal Corps advertised for bids for a heavier-than-air flying machine, and the Wrights made a bid on February 1, 1908, to furnish the War Department with an aircraft that would be capable of carrying two men and sufficient fuel supplies for a flight of 125 miles, with a speed of at least 40 miles an hour, and would ‘permit an intelligent man to become proficient in its use within a reasonable length of time.’ Two pilots had to be trained by whoever won the competition. The Wrights stated they would furnish a machine for $25,000 in 200 days that would fly at a speed of 40 mph with two men aboard. Their bid was accepted on February 8.

As soon as the specifications were announced, newspapers across the country criticized the move as a waste of taxpayers’ money. The New York Globe editorialized: ‘One might be inclined to assume that the era of practical human flight had arrived….A very brief examination of the conditions imposed and the reward offered for successful bidders suffices, however, to prove this assumption a delusion….Nothing in any way approaching such a machine has ever been constructed–the Wright brothers’ claim still awaits public confirmation.’

In March 1908 the Wrights signed a contract with Lazare Weiller, a wealthy Frenchman, to form a syndicate that would control the right to build, sell or license the Wright plane in France. They had already applied for patents in France, Britain and Germany to safeguard various parts of their creation.

The Wrights now had two contracts to fulfill, but the competition was rapidly taking the potential market away from them. The construction secrets that the brothers had wanted to protect were soon revealed in other aircraft, most notably by Glenn Curtiss, whose Red Wing and June Bug models were first flown in 1908. French pilots Gabriel Voisin, Henri Farman and Lon Delagrange and Romania’s Traian Vuia had flown briefly in machines of their own design. Alberto Santos-Dumont had also managed to get a plane into the air, but he couldn’t figure out how to make turns–and his longest flight was only 722 feet.

The brothers returned to Kitty Hawk in April 1908, where they hoped to build six planes by summer’s end. They repaired the old buildings and practiced in the 1905 Flyer, altering it to meet the Army specifications. As they reported in a magazine article: ‘The operator assumed a sitting position, instead of lying prone, as in 1905, and a seat was added for a passenger. A larger motor was installed, and radiators and gasoline reservoirs of large capacity replaced those previously used.’ They took up a passenger, Charles W. Furnas, for the first time on May 14, and within two weeks had made 22 flights, most of which were observed by newspaper and magazine reporters.

At that point Wilbur and Orville decided it would be best for them to separate in order to fulfill their contracts. Orville would build a 1908 Flyer and fly it to comply with the specifications of the Army Signal Corps contract. Wilbur would go to Europe, assemble the 1907 Flyer that was still waiting on the docks at Le Havre and demonstrate it for potential buyers.

Wilbur arrived in France on May 29, 1908, and spent much of his time trying to locate a suitable field. He repaired the plane, which had arrived in bad shape because French customs officials had carelessly renailed the boxes after their inspection. Electing to fly it at a racetrack at Hunaudires, near Le Mans, he was surprised to learn that the British and French press were hostile to him. Few Europeans, it seemed, really believed that the Wrights had actually flown as they had claimed. Hurt by that reaction, Wilbur at first avoided spectators and refused to grant interviews.

Without fanfare, he made his first flight on August 8, 1908. Although he flew only a little over two miles and was aloft just one minute and 45 seconds, he showed such control in the turns that the French skeptics were amazed. He flew daily for the next five days (never on Sundays) and increased his times and distances in the air to the point that he circled the field seven times. In a letter to Orville, Wilbur said, ‘You never saw anything like the complete reversal of position that took place after two or three little flights of less than two minutes each.’

The field at Le Mans soon proved too small, and he moved to nearby Camp d’Auvours, where ever-larger crowds gathered each day. The French press began to praise his flights in glowing terms. Le Figaro, a leading French newspaper, declared the Wrights’ plane ‘was not a success; it was a triumph!’

Meanwhile, Orville was carefully preparing for the trials at Fort Myer, Va. He made his first flight on September 3, 1908, and during the following two weeks went up a total of 14 times, establishing records for duration almost every time he flew. His longest flight was one hour and 14 minutes, during which he circled the field 71 times. He also carried aloft both Lieutenant Frank P. Lahm and Major George O. Squier on test flights to prove that the plane could safely handle two passengers.

Apparently there was some degree of friendly competition between the brothers. When Orville set a record, Wilbur was reportedly more pleased than anyone else–and promptly went out to set one of his own. London’s Automotor Journal editor observed that it seemed ‘just a case of what was naturally to be expected, with better to follow.’

On September 17, Orville had a tragic accident, the first in a Wright aircraft. While he was flying with Lieutenant Thomas E. Selfridge as a passenger, the plane crashed and Selfridge was killed. Orville sustained a broken thigh, several broken ribs and cuts and bruises. The accident was traced to a propeller that split and caused the housing and chain drive to vibrate. One of the guy wires running back to the tail had torn loose, resulting in Orville’s losing control of the plane.

Wilbur was shocked and saddened to hear of the accident but decided to continue his own flying in France whenever the weather was favorable. In following weeks he wrote encouraging letters to his brother, telling him in great detail of his flights and the prizes he had won. Wilbur had carried his first European passenger, French balloonist Ernest Zens, on September 16. A few days later he flew 40 miles in one hour and 31 minutes without a passenger. On October 6 he flew with Arnold Fordyce for one hour and 4 1/2 minutes, the longest flight in duration yet made by two persons. This flight fulfilled the requirements of the Wright contract with Lazare Weiller, which called for the payment of $100,000 to the Wrights and gave the French syndicate the rights to manufacture and sell Wright airplanes in Europe.

The next day Wilbur carried Edith Berg aloft, giving her the honor of being the first woman passenger to fly in an airplane. Conscious of what the wind might do during the flight, he cautiously tied a rope around her long skirts before they took off. Berg inadvertently started a new fashion trend, the hobble skirt, when she was photographed with the rope still firmly holding down her skirts after the flight.

By this time Wilbur was worldwide news, but he was still reticent about granting interviews. After much coaxing, he agreed to accept an honor from the Aero-club de la Sarthe–on the condition that he did not have to give a speech. When the audience begged him to talk, he shook his head no, then rose slowly to his feet and said, ‘I know of only one bird, the parrot, that talks, and it doesn’t fly very high.’ He then sat down–to loud applause. His reticence only made newsmen more enthusiastic about this quiet, unassuming American, and they praised him abundantly in print. Wilbur later wrote to Orville, ‘Instead of doubting that we could do anything, they were ready to believe that we could do everything.’

Wilbur seemed to establish new records with each passing day. Since his contract called for training three pilots, he began teaching Comte Charles de Lambert, Paul Tissandier and Captain Lucas de Girardville on October 28. At that point prizes were being offered by the Aero-club de France to inspire French pilots to compete against Wright. First was a prize for attaining an altitude of 25 meters, and another for being the first to climb to 30 meters. Wilbur won both easily, climbing to 90 meters. On December 18 he set a new altitude record of 110 meters. That same day he also stayed aloft for one hour and 55 minutes. On the last day of 1908, he set a final endurance record of two hours and 20 minutes, and flew a record 77 miles to win the Michelin Cup. His total prize winnings amounted to 24,500 francs ($4,900). Between August 8, 1908, and January 2, 1909, he had made more than 100 flights in France.

In his letters to Orville, Wilbur wrote at length about his European endeavors. He seemed especially delighted with the attitude of many European writers, who had come to doubt but stayed to praise. In one letter he noted: ‘Every day there is a crowd of people not only from the neighborhood here, but also every country of Europe. Queen Margharita of Italy was in the crowd yesterday. Princes and millionaires are as thick as flies.’

When Orville had recovered sufficiently from his accident, Wilbur wanted him and their sister Katherine to join him in Paris. They arrived in early January 1909. Orville, still limping and saddened by the death of Selfridge, did not intend to do any flying. Meanwhile, Wilbur had moved his operation to Pau, a resort town in the south of France where the weather was warmer, and he had departed to resume his flying. Ironically, while en route to Pau from Paris to join him a few days later, Orville and Katherine barely escaped injury in a train wreck.

Wilbur made his first flight at Pau on February 3, 1909, and thereafter continued training Lambert, Tissandier and Girardville. In so doing, he established the world’s first flying school. He remained at Pau until March 20, and dignitaries from several nations visited him there, including King Alfonso XIII of Spain and England’s King Edward VII. The Wrights returned to Paris briefly, then Wilbur entrained for Centocelle, near Rome, on March 28 to demonstrate their Flyer and also train two pilots for an Italian company that had been formed to acquire a plane. He made 42 flights there beginning in mid-April, half of which were training efforts with Italian army and navy officers and other passengers. On one flight, he permitted a ‘bioscope’ cameraman from the Universal News Agency to fly with him and photograph the surrounding countryside, thus producing the first motion pictures taken from an aircraft in flight. He was joined by Orville and Katherine for a month, then the three of them went to Paris and London, where the brothers received awards and called on military leaders. They returned exhausted to the States in May, where they received a rousing two-day homecoming celebration in Dayton, including cannon salutes, a parade, a 10-minute factory whistle salute and fireworks. During their sojourn in Italy, the Wrights had received an offer from some wealthy Germans to form a German Wright company, build planes and obtain sales rights to five other countries. They signed a preliminary contract that meant they would receive cash, stock and a 10-percent royalty on all planes sold.

Orville’s visit to Europe had provided the newsmen, who now followed both brothers relentlessly, even more incentive to publish material about the Wrights. By that time their fame was also resulting in additional–and unanticipated–problems. At Pau, Wilbur learned of a report in the Dayton Daily News that he had been named as a co-respondent in a divorce suit filed by a Lieutenant Goujarde. He rushed off a letter to the editor saying that the report was entirely without foundation. The news service that had sent the item, after an investigation, discharged its reporter and apologized to Wilbur.

While Wilbur was in Europe, a joint resolution had been introduced in the U.S. Congress to award a medal ‘in recognition of the great service of Orville and Wilbur Wright, of Ohio, rendered the science of aerial navigation in the invention of the Wright aeroplane, and for their ability, courage, and success in navigating the air.’ The Smithsonian Institution also recommended that the newly established Langley Medal be awarded to the brothers ‘for advancing the science of aerodromics in its application to aviation by their successful investigations and demonstrations of the practicability of mechanical flight by man.’ They also received medals from the state of Ohio and the city of Dayton.

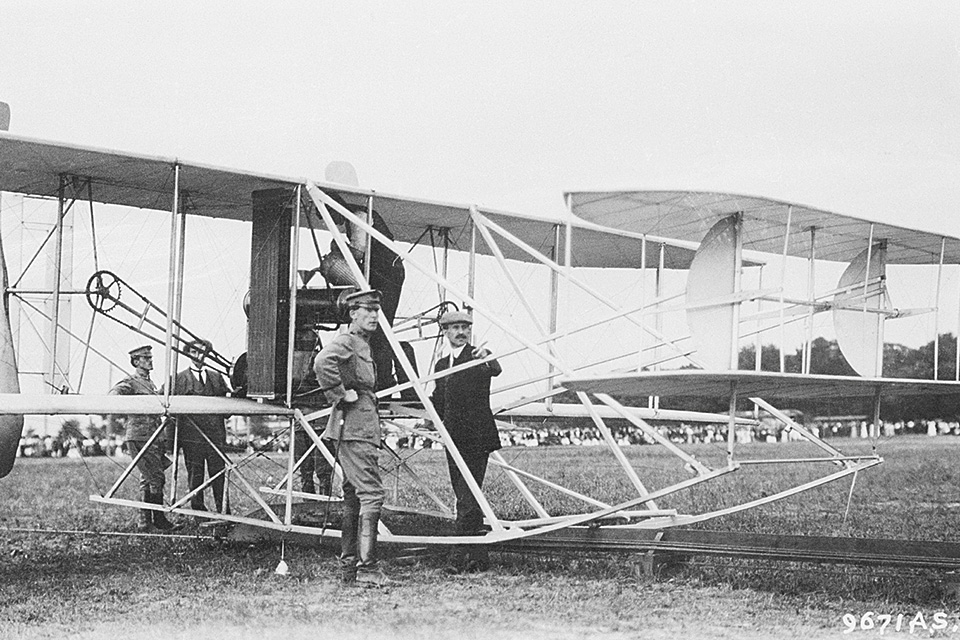

Once the homecoming celebrations were over, Wilbur and Orville decided it was time to return to Fort Myer with a new plane and complete the Army flight tests. They arrived in Virginia with their latest Flyer on June 20, 1909, and the first series of flights began on June 29.

There was an unspoken agreement that Orville would be the pilot for the trials, even though he had not flown since the accident. On July 27 Orville announced to the Aeronautical Board that he was ready to resume testing. He chose to comply with the specification calling for a ‘trial endurance flight of at least one hour’ and another requiring that the plane ‘be designed to carry two persons having a combined weight of about 350 pounds.’ He chose tall, slim Lieutenant Frank Lahm to fly with him, and complied with both requirements by staying in the air for one hour, 12 minutes and 38 seconds, a world record for a two-man flight. That flight was witnessed by President William H. Taft, his cabinet, other high-level government officials and an estimated 10,000 spectators.

On July 30 Orville told the Aeronautical Board that he was ready for the cross-country and speed test. He chose wiry Army Signal Corps Lieutenant Benjamin D. Foulois as his passenger and navigator for the 10-mile cross-country flight. The course was from Fort Myer to Shuter’s Hill in Alexandria, Va. They circled a captive balloon used as a marker and returned to Fort Myer, setting a record for two-man flight at a speed of 42 1/2 miles per hour to complete that phase of the contract. However, they still had to train two Army pilots.

The pilots assigned were Lieutenants Lahm and Frederic E. Humphreys, a Corps of Engineers officer, and this time the training was conducted at College Park, Md. The brothers decided that Wilbur would do the instructing while Orville went to Germany, where the German Wright company had already been set up. He and Katherine arrived in Berlin in late August 1909. There Orville flew one of the German-manufactured planes at Tempelhof Field on September 4. He set an altitude record of 565 feet on September 17 and also established an endurance record with a passenger of one hour and 35 minutes. He tried for another altitude record on September 30, climbing to an unofficial height of 902 feet. Most of his flights were witnessed by the German royal family.

When Orville returned home, both men felt that it was time to size up their future. They were now involved in about 20 legal actions to protect their patents. The Wrights by then had held the world’s attention for two years, achieving fame and fortune beyond their dreams. Between September 1909 and the end of 1910, they had received over $200,000 in the United States alone, including $30,000 for the first Army plane, $15,000 for Wilbur’s flights while Orville was in Germany, $100,000 for the formal organization of the Wright Company on November 22, 1909, and more than $50,000 in dividends and royalties. At this point, they had three possible courses of action: continue their flights and prove their superiority as the world’s foremost pilots; devote their attention to manufacturing aircraft and defending their patents; or retire from the aviation business and pursue other interests. They chose the second course.

But the invention they had brought to the world was being improved upon daily by other innovators, who were also advancing the frontiers of aeronautical knowledge. During 1910 the speed of aircraft had increased to more than a mile a minute; the distance record had increased to an astounding 244 miles in five hours, 32 minutes; the altitude record had reached 8,692 feet; and engine power had increased from 25 to almost 100 horsepower. The Alps had been crossed by air, flights had been made from London to Paris, and four passengers had been successfully carried aloft with a pilot.

Despite the Wrights’ initial successes, the European nations were then developing aircraft of their own more rapidly than the United States. In March 1911 Wilbur went to Europe to prosecute patent infringements. Orville later returned to Kitty Hawk to experiment with an automatic control device on a glider. There were so many newsmen around, however, that he never tested it, for fear that it would be copied–although he did make 90 glides and set a soaring record of nine minutes and 45 seconds, a record that lasted almost 11 years.

Time and the struggle to defend their inventions were taking their toll on the Wrights. They purchased a 17-acre plot of land in a Dayton suburb and began planning a new home for themselves and their sister. But shortly after their first visit to the site Wilbur became sick. At first it was thought that he had only a slight illness, but he was soon diagnosed with typhoid fever. Fatigued and stressed by the many court battles he and his brother were still fighting, he could not summon sufficient strength to overcome the illness. Wilbur Wright died on the morning of May 30, 1912. In his diary, Bishop Milton Wright marked his 45-year-old son’s passing with a short eulogy, which seems to sum up both Wilbur’s character and career: ‘…A short life, full of consequences. An unfailing intellect, imperturbable temper, great self-reliance and as great modesty….’

A grieving Orville, now 41, assumed the reins of the Wright Company as its president. Flying had by now become big business. Besides the lawsuits against alleged infringers of the Wrights’ patents, aircraft manufacturers in Europe had copied the Wrights’ control system and designs without benefit of license. He willingly gave up his position three years later, in August 1915, when a syndicate headed by William B. Thompson purchased Orville’s stock interest, retaining him as chief aeronautical engineer.

With the death of the one brother, the world of aviation had also lost the brilliance of the other. Orville would never again seriously experiment, devise or invent. He did, however, test a hydroplane and other models between 1913 and 1916, and made a series of flights with an automatic stabilizer. He had only one reported crash: On August 21, 1914, while flying a hydroplane with Navy student pilot Kenneth Whiting, a wing collapsed and the plane fell into the Miami River. The two narrowly escaped drowning.

Orville last flew as a pilot on May 13, 1918, when he piloted a 1911 Wright biplane in formation with a Liberty engine de Havilland D.H.4 that was being license-built by the Dayton-Wright Airplane Company–which he had joined as a technical adviser the previous year. By that time he appeared only occasionally in public. He briefly recaptured the media’s attention in January 1928 when he shipped the repaired 1903C Flyer to the Kensington Museum in London ‘because of the hostile and unfair attitude shown towards us by the officials of the Smithsonian Institution.’

Orville died after two heart attacks at the age of 77 on January 30, 1948, and was buried in Dayton beside his brother. Their Flyer was returned to the Smithsonian the following December.

The famous brothers had triumphed as entrepreneurs and achieved what some of history’s greatest minds had not been able to accomplish. Not only were they the first to build and fly a powered flying machine, they also founded the science of aeronautical engineering and set the world’s course toward the stars.

This article originally appeared in the November 2003 issue of Aviation History and was written by C.V. Glines, an award-winning aviation author and a member of Aviation History’s advisory board. For further reading, try: The Published Writings of Wilbur and Orville Wright, edited by Peter L. Jakab and Rick Young; or Kill Devil Hill, by Harry Combs with Martin Caidin.

For more great articles subscribe to Aviation History magazine today!