Gravy’s so easy to make — just mix meat drippings and a pinch of flour to thicken it and you are done. But the pan-scraping sauce, particularly creamy white gravy, has had a surprising sojourn throughout history. Along with its cousins gruel and chocolate gravy, it makes up part of a family of simple, filling foods that anyone can make and nearly everyone enjoys.

And though its legacy is wide, white gravy’s chief contribution to American military cuisine may be one that soldiers, sailors, Marines and airmen loudly profess to loathe — but that they actually seem to love.

But before we get to that, a brief history of white gravy and how it led to the military staple known as “SOS.”

WHITE GRAVY AND CHOCOLATE GRAVY

White gravy, the broadly Southern staple found blanketing chicken fried steak and biscuits, is a version of a fancier sauce. Actually François de la Varenne, chef de cuisine for Louis XIV’s diplomat Nicolas Chalon du Blé, gets credit for first concocting it. La Varenne authored the world’s first commercial cookbook, “Le Cuisinier François” (“The French Cook”), and the recipe for béchamel sauce accompanied early French explorers to Louisiana, where meatier variants soon followed.

One cousin of white gravy is the lesser-known chocolate option. In the early 1500s, one of the most prized spoils from the Spanish conquest of the Americas was the secret of the cacao tree, the seed of which forms the basis for chocolate. This discovery led to the eventual transport of the precious commodity of chocolate to the Spanish-held territories of Louisiana and Texas in later years.

At some point, very possibly along the frontier between Spanish Louisiana and the first-British, then-American-held Tennessee Valley, the chocolate was mixed with other ingredients to formulate a sweetened version of the gravy with the same purpose, poured over pancakes, biscuits, and the like, gradually spreading throughout the Upland South. Folks in the Ozark Mountains use this version of gravy nowadays more often than they do along the coastline.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

GRUEL, WHITE GRAVY’S UNLOVED COUSIN

On the other hand, white gravy’s distant relative gruel suffers from a stigma. Gruel is typically associated with both the sick and downtrodden; the fact it rhymes with “cruel” does not help its standing. However, Ursuline nun Marie-Madeleine Hachard excitedly wrote her father in 1727 about the wonderful food in Louisiana. She seemed almost giddy, expounding, “We are getting remarkably used to the wild food of this country … rice cooked in milk [gruel] is very common and we eat it often ….”

In the mid-1700s, Native American tribes in Louisiana offered a resident Frenchman, Lt. Dumont, a similar type of mixture that he described as gruel made from husked maize, water and oil from bear fat. Dumont, receiving this repast in return for some gifts and trinkets, noted, “The French eat it on salads and also … for making soups.”

(White gravy on a salad is quite a concept!)

GRUEL AS MIRACLE CURE

A century later, gruel was reintroduced across the United States via an 1860 marketing surge driven by its supposed medicinal value. Newspapers were saturated with advertisements lauding its “invigorating” qualities. One particular brand of gruel claimed to be helpful to children as well as “highly useful and beneficent to Women in the state of Pregnancy.”

During the Civil War, Ransler Wilcox of the 49th Massachusetts Infantry was stationed in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, and jotted this in his diary: “I do not feel well … have been to the doctor and got some medicine … gruel for dinner … tea and gruel for supper.”

Samuel Haskell of the 30th Maine Infantry on duty at Morganza, Louisiana wrote, “I have been sick [and] I dare not eat the rations we draw … [we can get] every thing but flour …. I have bought some to make some grewall.”

Modern postnatal care research papers have lauded its benefits in artificial infant feeding. Maybe there is something to this aspect of gruel being a cure for your ailments after all.

In the aftermath of the Battle of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, in July 1863, women from the surrounding area flocked to the battlefield to assist with the large number of wounded soldiers. Supplies being minimal, the makeshift hospitals resorted to whatever was at hand to ease the pain and hunger of the injured men.

Farina is mentioned in lots of reminiscences from nurses and ladies of the Sanitary Commission. The caretakers would add water or milk to the farina and heated it to a palatable gruel mixture. This allowed the comforting, warm food that would stretch to larger groups of troops. The concoction was also very nourishing and easy to eat and digest.

One Union soldier marching through the south recalled: “Many a soldier will remember how, when he fell out of the ranks during one of those severe marches, and the planter nearby scowled and glowered so that he could not enter the rich man’s door,” some sympathetic slave woman “helped him to her own cabin . made him tea and gruel, and nursed him as tenderly as his sister would have done.”

Recommended for you

GRAVY ON THE GO

During the 1864 Red River Campaign, Lt. George G. Smith of the 1st Louisiana (U.S.) Infantry put the two staples of rations together out of necessity. All he had available to eat was “a piece of boiled salt pork, a few pieces of hard tack and some coffee. Salt pork I could not, and hard tack I would not eat.”

Finally, Smith decided, “I will soak my hard tack in some hot water and soften it up a little, and fry some of the salt pork in my tin plate and then fry the soaked hard tack in the gravy. Very good!”

After creating the makeshift white gravy, Smith noticed comrades were watching the process. Within a week, instead of garnering the credit for the mixture, he noticed the entire camp was relishing the new dish made from items everyone had in their haversacks.

Whether a remedy for sickness or not, anyone who has ever read the book or watched one of the numerous movie versions of Charles Dickens’ classic “Oliver Twist” surely recalls the protagonist uttering the plaintive line about gruel: “Please, sir, I want some more.” One can assume this is the juncture where being orphaned, poor and homeless became associated with the term “gruel.” The derogatory meaning associated with the word has even found its way into mainstream media thanks to a statewide sports column. Headlines of a postseason loss for Louisiana State University football a few years back opined, “LSU’s holiday bowl gruel typified a mushy season.”

S*** ON A SHINGLE

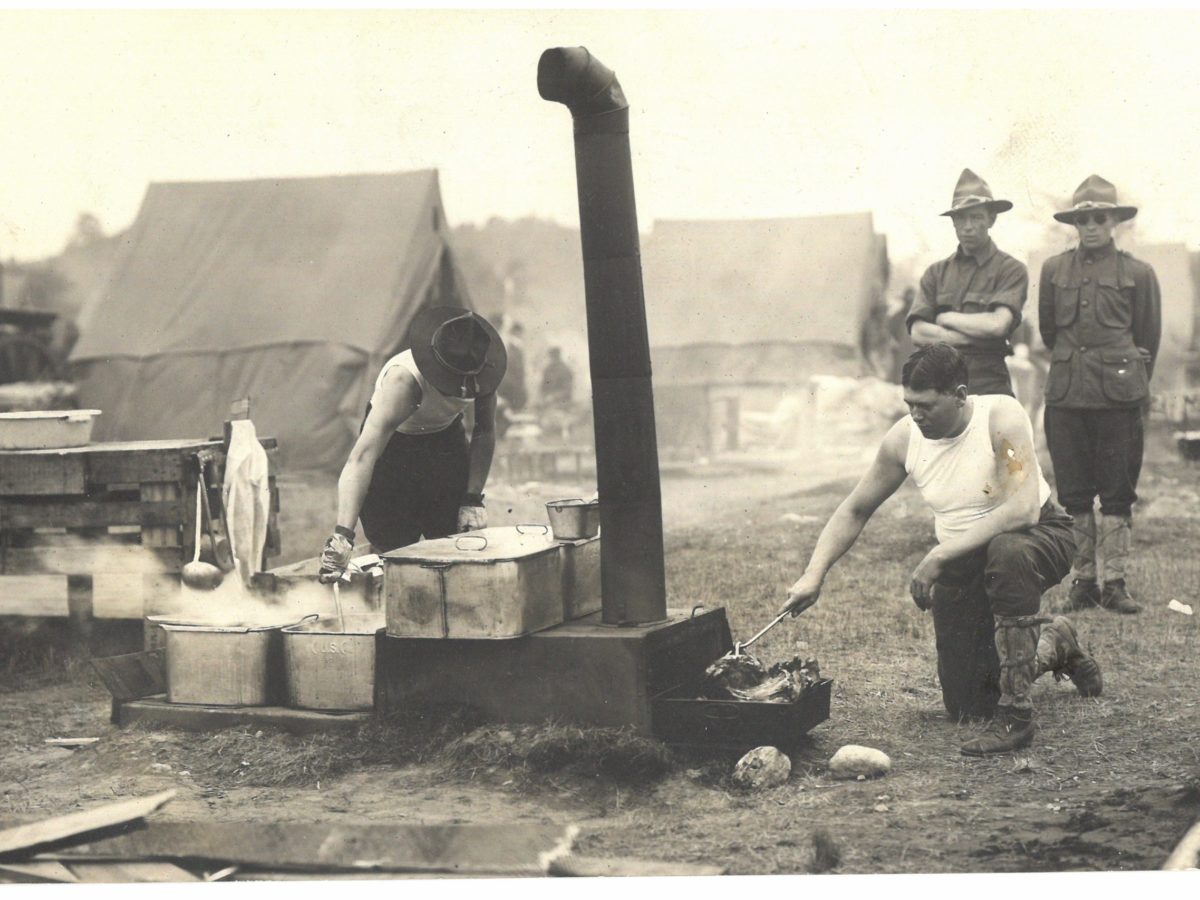

White gravy has ingratiated itself with the United States military; for example, add sausage and you have sawmill gravy. Chipped beef even found its way into the white gravy mixture with the future doughboys right before World War I.

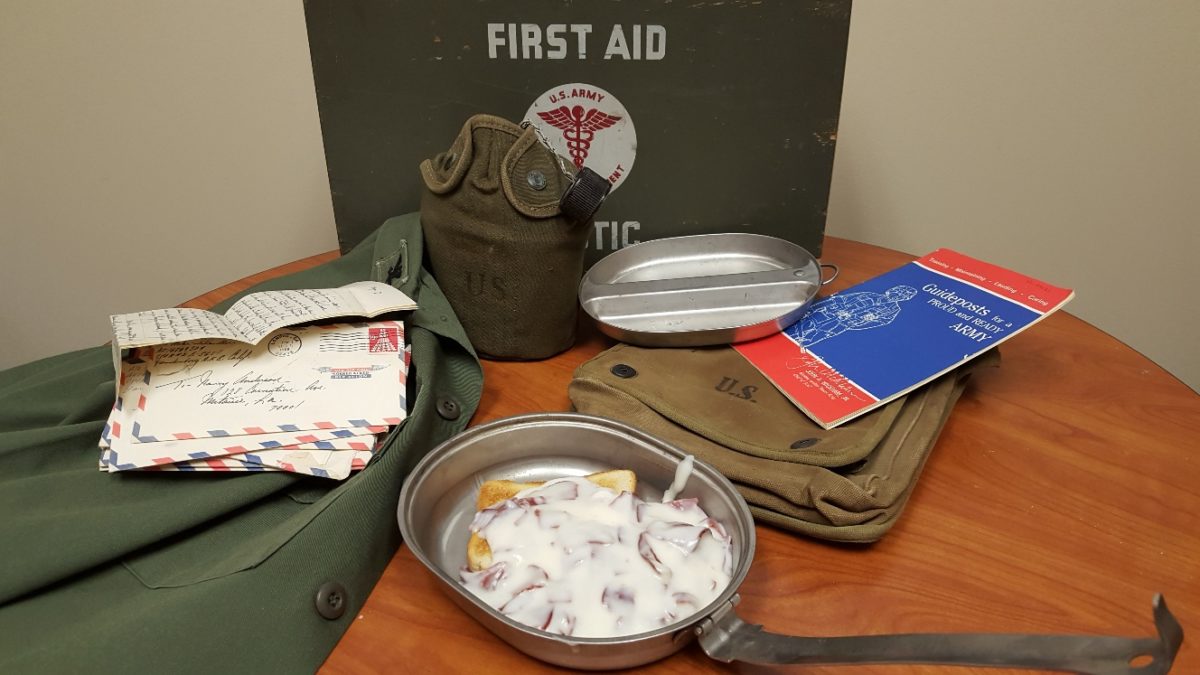

Soldiers and sailors eventually dubbed it “SOS” (“Save Our Souls” or “Same Old Slop” being the PG-rated translations) when served on a piece of toast. The very first documented proof of the military making SOS was the 1910 “Manual of Army Cooks.” Field conditions caused some ingredients to change due to availability but for the most part the stuff used to make the concoction for the troops included … well, see for yourself.

Recipe #251. Beef, chipped: 15 pounds of chipped beef; 1 pound fat, butter preferred; 1½ pounds flour, browned in fat; 2 12-ounce cans of evaporated milk; bunch parsley; ¼ ounce of Pepper; 6 quarts of beef stock

Before you start cooking this up, please realize you have to invite 59 friends over to consume this massive portion with you, as it was measured out to feed 60 hungry soldiers.

One of the stories of the famous “Band of Brothers,” Easy Company of the 506th Parachute Regiment of the 101st Airborne Division, happened stateside, before they crossed the ocean to fight the Germans in World War II. They boarded a train bound for Sturgis, Kentucky. At the railroad depot, women from the Red Cross gave them doughnuts and coffee. The soldiers camped outside of the town and were treated to what seemed to be the Army’s meal of choice to offer troops in the field, creamed chipped beef on toast.

Gerry Stearns of the 89th Infantry Division recalled his experiences with SOS in World War II.

“Sometimes the GI’s names for staples could have been off-putting,” he wrote. “The Mess Sergeant’s menu listed ‘cream chipped beef on toast.’ What we called it was ‘Something on a Shingle,’ or usually ‘S.O.S.’ I was uneasy about trying that until about three or four o’clock one morning I was checking the buildings of the reception center where I was a limited service MP. There was an interesting smell of frying meat as I approached the mess hall. I am pretty sure my General Orders required me to investigate. What I found were mounds of hamburger being cooked in big pans, a milk and flour sauce being prepared and hundreds of bread slices being toasted. I became an instant fan and a regular participant in this and many subsequent S. O. S. Breakfasts.”

SOS TAKES OFF

SOS grew in popularity during both world wars and in Korea and Vietnam. Near the end of World War II, the Army published the recipe in “TM 10-412” in August 1944 but made a few changes in the previously standard ingredients. The parsley and beef stock had been removed in an effort to make a creamier chipped beef serving. It was a success, but cooks still had to be reminded to soak the chipped beef beforehand to remove the preservative salt. The U. S. Air Force joined in serving SOS in World War II and through the next few wars.

Dennis Peterson of the 309th Tactical Fighter Squadron fondly recalled many SOS meals during the Vietnam War.

“Good eating,” Peterson wrote. “It [SOS] was always available on the food tray. Eggs and bacon were my preference, but SOS was delicious, too.”

Becoming a professional truck driver after the war, Peterson would often sample similar food on his travels across the Southern United States roadways.

The U. S. Navy had their own varied ingredients, which included tomatoes, fresh ground beef and nutmeg. One sailor commented that his ship got upset when they were given the SOS with chipped beef Army variant instead of the minced beef style they had been served for so long. They eventually convinced the cooks to restrict the chipped beef version to once a year.

Interestingly enough, if you look through any Navy cookbook from 1927 until 1952, you will find that there is no recipe for making creamed beef. Hands down, they preferred minced beef, something unique to their branch of service. The only other group to eat it were U. S. Marines being transported on Navy vessels. A Navy cook was taught to thicken the tomato sauce for the minced beef with cornstarch. Their nautical SOS was served for an entire week and then alternated the next week with corned beef hash and hard-boiled eggs and so on throughout the year.

“Probably because space is such a premium aboard ship, we did not have chipped beef, just good old hamburger meat, minced with plenty of black pepper and salt, “ said U. S. Navy Cook Striker (apprentice) Jon Lord, aboard the U.S.S. California from 1974 to 1975. “It was more of what today we would call sausage gravy. We fed 450 men, three times a day at sea. Breakfast was the favorite meal. As I recall, there would be one or two meats on the line every morning: bacon, sausage, ham, or SOS. SOS was always a crew favorite.”

SOS TODAY

More recently, some branches of service have decided to go with a healthier SOS, using very lean ground beef (less than 10% fat) or implementing ground turkey to provide the meat in the meal. Regardless of the mixture, the popularity of this dish has persevered in the military over the years.

In the aftermath of the disastrous Hurricane Katrina along the Gulf coast in 2005, the makeshift kitchens at Camp Beauregard in Pineville, Louisiana, were full of continuous large containers of the white gold, this version mixed with ground beef. This was used to fill the many hungry stomachs of the various units from across the United States sent down on rescue missions throughout the state and nostalgically housed in the old World War II-era barracks on post. Considering the disaster areas they were confronting on a daily basis and the shortage of generators on post, the warm, tasty SOS made a lasting culinary experience akin to the earlier days of the military camp.

In garrison situations, the Army SOS would be served over toast. In field-based scenarios, the SOS would be put atop baking powder biscuits.

“Since the cooks started to cook breakfast before sunrise, they had to work under blackout conditions,” one cook said later. “The walls of the mess tent were drawn, and the cooks had to work with flashlights. This was important because you could see a cigarette for miles.”

But whether you can see it or not as you eat, SOS or chipped beef, or whatever you prefer to call it, has seemingly made itself a permanent home in America’s military mess halls.

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.