The weary soldiers of the 1st Louisiana Infantry disembarked from their train in San Benito, Texas, early in the summer of 1916. Disoriented after the long trip from Camp Stafford in Pineville, Louisiana, the foot soldiers quickly got their bearings when they were ordered to set up their pup tents in a dusty field along the edge of town.

The Louisianans completed their task quickly as the heat of the day bore down upon them. On one side of the newcomers stood the camp of the 1st Oklahoma Infantry while the other side contained the troops of the 4th South Dakota Infantry. At the end of all three unit’s campsites stood the worn buildings of the city, its citizens soon growing accustomed to their new residents.

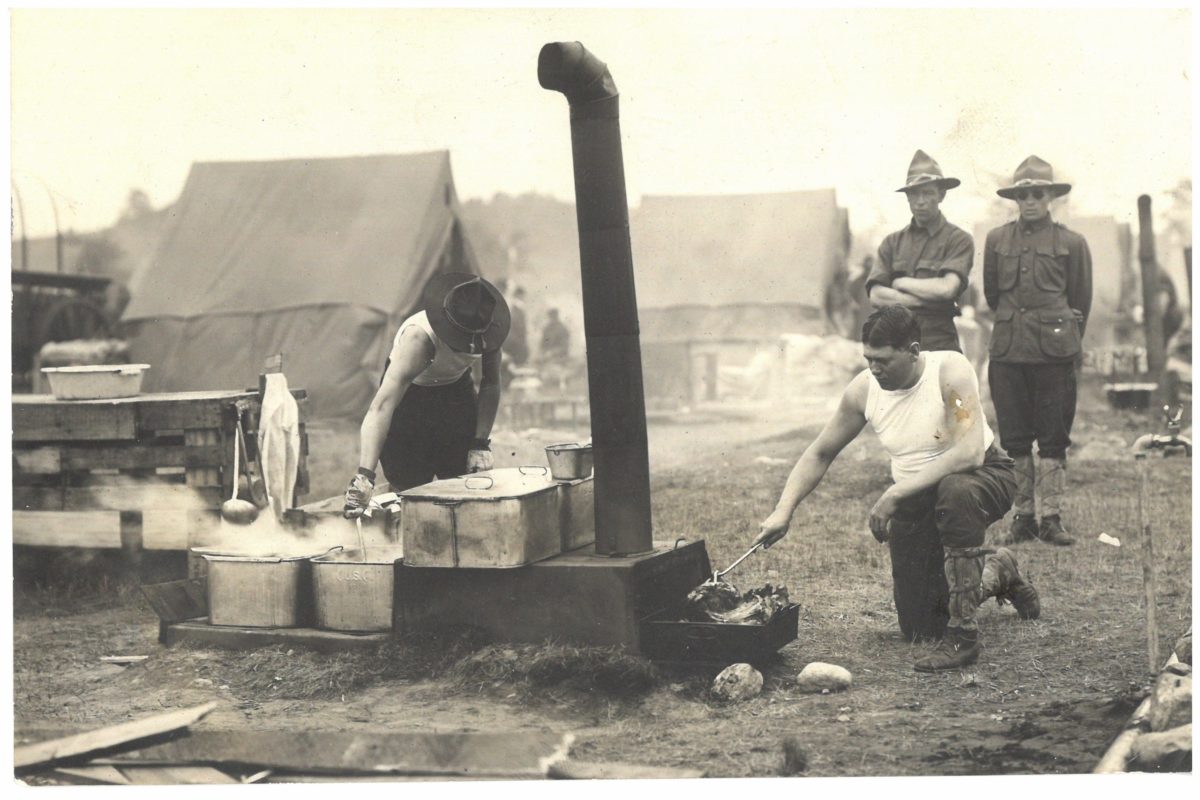

The culinary staff of Col. Francis P. Stubbs’ Louisiana regiment unloaded their field equipment in order to begin a meal for their comrades in arms. Initially, their cooking facilities had already been set up for them inside of one of the converted boxcars set up as a makeshift dining hall.

SETTING UP THE KITCHEN

First off the train was their collection of brand new U.S. Army field ranges, one for each of the 10 companies. The version the Louisianans used, Model No. 1, was a 264-pound monstrosity, complete with utensils. The stoves were also augmented with “Alamo” attachments, which allowed them to prepare enough meals to feed up to 150 troopers. Holes were dug to partially embed the stoves into the ground, the base lying in a 2-foot-deep bed of cobblestones.

Then the soldiers removed the tools of the trade stored inside the oven, each appliance containing pans, knives, cleavers and other utensils, even a fire-iron set. The cooks were also encouraged by the army’s directives to use wood in this latest stove instead of coal, a requirement quickly remedied by hungry soldiers with axes.

Time was of the essence, as the men in the ranks would be hungry after their assigned tasks, so each company cook was ordered to prepare a simple but hearty fare. The menu that day was to be fried bacon with both German boiled and French baked potatoes, which were standard preparations made straight out of the brand-new “Manual for Army Cooks.” Each recipe was based on an average of 60 men and carefully measured out.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

LOUISIANA’S TALENTED MILITARY COOKS

When everything finished cooking, the infantrymen lined up with the plates and silverware and ate the filling meal. While their neighbors to each side consumed similar Army-style food prepared the exact same way, the Louisiana troops would not long stand such a bland repast. In fact, it was a standard practice for each company to switch cooks on a regular basis to provide the men in the ranks with varied culinary styles, so for Louisiana troops that meant Cajun style one day, Creole the next, followed by Spanish-influenced dishes.

Though the cooks may have been officially called that name in the military, they were in fact employed as professional chefs working in restaurants located across the Bayou State. So, while they adhered to rules and regulations for guardsmen, these culinary masters managed to smuggle their own favorite ingredients along with them on the trip. Cook George Graham was a stalwart chef at the Mirror Room Restaurant in the Hotel Bentley in Alexandria, while Cook J. B. David had been a chef at the Costello Hotel in Morgan City. Cook William Fink was a chef in the heart of the French Quarter of New Orleans at the Royal Restaurant. Many chefs had not ever left the state before now, so they were not aware of what might be available in the way of groceries in the sleepy Texas town.

BORDER PATROL OR BOREDOM PATROL?

The soldiers in the San Benito area were all a part of a campaign dubbed the Punitive Expedition, orchestrated by the United States government in response to recent raids into American soil. These raids were carried out by a small army led by Pancho Villa. These self-styled “Villistas,” or at least 485 of them, raided the town of Columbus, New Mexico, on March 9, 1916, leaving in their wake a total of 18 dead and nine wounded Americans, both soldiers and civilians.

Tabbed to lead the American forces in response to these heinous criminal excursions was Brig. Gen. John J. “Blackjack” Pershing. Not satisfied with the nearly 6,700 Army regulars available for such a vast area to patrol, National Guard units from each state and the District of Columbia, totaling 110,000 men, were ordered by President Woodrow Wilson to assist Pershing. This maneuver had been authorized by Congress with their passing of the National Defense Act of June 3, 1916. As the individual National Guard organizations initially deployed to different positions along the Mexican border, Villa’s bandits made three additional sorties into Texas.

Although the regular troops managed to get into actions chronicled by many of the country’s newspapers, the men in the National Guard units fought a more serious enemy called boredom. These militia groups were prevented from crossing the border into Mexico, so they had plenty of time on their hands.

Commanders of the regiments stationed in San Benito realized idle hands were not good for morale. Collectively, the three state units there were under the command of a brigade commander, Col. R. L. Bullard, who offered several key suggestions to keep everyone busy. The three regiments started a weekly newspaper called The Oklasodak, derived from the abbreviations of the states the men came from. The men were also given assignments to construct entrenchments next to important local installations. Troops also made regular trips into town to familiarize themselves with the local businesses and purchase postcards and stationery to send missives home. Being away from home, many men tried to befriend members of the local community and support its businesses, forming fast relationships.

Recommended for you

THE SECRET INGREDIENT

When they had the opportunity, each unit would bolster the spirits of their soldiers stationed so far away from home with such fun events like flapjack eating contests. While their comrades from Oklahoma and South Dakota created standard pancakes with syrup for a topping, the Louisiana chefs used special recipes to delight the palate. The actual pancakes were made close to how the others made theirs, including using the morning’s bacon grease to keep them from sticking to the pan.

What set the Louisianans apart from the rest was the topping they used, a centuries-old creation.

In the early 1500s, one of the most prized spoils from the Spanish conquest of the Americas was the secret of the cacao tree, the seed from which forms the basis for chocolate. This discovery led to the eventual transport of the precious commodity to Spanish-held Louisiana in later years. Eventually, residents mixed it with some other ingredients to make a dish hailed as white chocolate gravy. This delicious recipe would replace regular syrup being served on flapjacks and biscuits in many Louisiana homes for decades to come.

While chocolate was not an item that made the trip from Louisiana due to the summer heat conditions, much to the delight of the chefs there were chocolate vendors on nearly every local street corner in San Benito to satisfy the Louisianans’ needs to make their tasty delicacies.

WAR BABIES, FRESH FISH AND MILK FOR THE COFFEE

As the soldiers of the 1st Louisiana settled into a regular routine, good news arrived, as one of their officers from Bogalusa, Louisiana, was greeted with the first “war baby” in Bullard’s brigade. The proud father, 1st Lt. R. L. McLean exclaimed he “feels like he could whip the whole Mexican army right now,” further emboldening the charges under his command and within the regiment.

The men continued to find enjoyable distractions to occupy their time. The craving to read elevated in popularity, causing a strain on the local availability of books. Even flying a kite became popular as it lent itself to the frequent strong winds.

Fishing also became a favored pastime among all of the groups. The “finny tribe,” as they were nicknamed, contributed heavily as an alternative to the normal rations of red meat. Even live shrimp managed to wash into the river, which provided an even more familiar ingredient to the Louisiana kitchen staff.

The fish were prepared Delmonico style, while the shrimp were made in many different Louisiana variants, among them Cajun shrimp with a garlic-Parmesan cream sauce or the simpler fare of fried shrimp. Both recipes required fresh milk, which was not available in camp. The chefs simply sent one of their kitchen staff to get some milk from either the local San Benito Dairy or J. E. Smith’s Dairy. These assignments to forage for milk were a regular occurrence considering the number of Louisiana recipes requiring the precious white liquid.

Also in need of milk was Creole coffee that often filled the canteens of the Louisiana men. While café noir was served black, café au lait needed a touch of milk to make it right. In true Creole style, they always dripped their coffee, as boiling would remove the delicious flavor.

MILITARY FOOD TO WRITE HOME ABOUT

Both the Oklahoma and South Dakota troops quickly became enamored with eating in the Louisiana camp. A Tulsa newspaper reported on the attraction of Cajun cuisine when they wrote, “The Louisiana cooks are spreading the gospel of good living too. Every invitation to take mess with a Louisiana company is accepted. For Louisiana has been famous all over the world for its cookery ….”

Even a far distant South Carolina tabloid noted, “The Creoles of Louisiana, famous for their cookery, are reported to use the young buds of the sassafras as a substitute for okra in thickening soups.”

However, observing the cooking process was best not done with a weak stomach. One South Dakota private was sickened to see dozens of turtles hanging from a clothesline with the blood draining from their bodies, an important process in making Creole Caouane [pronounced “cow-ann”], or turtle soup, using a dark brown Cajun roux and various vegetables and spices.

NEVER CUT IN LINE IN THE MILITARY

By far, the most shocking episode during the deployment of the Louisianans happened in a train car. At the end of July, the 1st Louisiana was recalled home as soon as possible at the request of their governor. The Louisiana soldiers started repacking their gear and began receiving their meals in the rail cars, cooked using their smaller permanent stoves. The enlisted men began getting their meals inside the small boxcar and eating outside.

Capt. Ralph B. Lister, depot quartermaster for the brigade at San Benito, stopped by to inspect the boxcar and its equipment. The captain was a rising star in the U.S. Army, having recently served with the 1st U.S. Infantry at Schofield Barracks in Hawaii before being promoted to assistant department quartermaster and simultaneously taking charge of all military transportation on the island. A native of New Jersey, Lister had been a captain with the 1st Colorado Infantry before receiving a commission in the regular army due to his notable service in the Philippines.

Lister had just entered the car when he found his path blocked by a crowd of enlisted men as they awaited their lunch. 1st Louisiana Sgt. William E. Kelly stepped up and tried to assist the officer in making his way through the crowd when they ran afoul of the cook for the day, George Graham. Heavily inebriated, Graham apparently mistook Lister and Kelly as skipping in line and lashed out with the meat cleaver he currently held in his hand. Lister was struck on the left side of the jaw and neck.

The gash was about 4 inches long and so deep it managed to sever the facial artery, causing a massive loss of blood, so much so it was initially feared to have nicked the jugular vein. The captain’s wound proved not serious, but he would carry the scar for the rest of his life. Kelly also incurred a head wound with the cleaver trying to shield Lister. Bystanders immediately restrained the maddened chef, who was soon imprisoned and court-martialed.

GOODBYE, RIO GRANDE

Within days, the men of the 1st Louisiana boarded the Pullman cars for their return to Pineville. On the day of their departure they presented Col. Bullard with a booklet containing an original play titled “To the Border and Back”:

“Of the girl left behind; the Mexicans; the rain and the brand-new kitchens were left behind causing one Louisiana soldier to query one of their officers upon their return to Camp Stafford, ‘I wonder who’s loving ’em now?’”

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.