Blood Horses

The Mongol Empire, which under Genghis Khan gobbled up vast swaths of Eurasia in the 13th century, boasted armies of highly mobile warriors whose horses provided them with both transport and, in a pinch, sustenance: Cavalrymen not only relied on sips of mare’s milk when wild game and other forage was in short supply but sometimes gingerly sliced a vein in their horse’s neck and swallowed a few mouthfuls of its blood. Marco Polo reported that by nourishing themselves in this way, Mongol horsemen could “ride quite ten days’ marches without eating any cooked food and without lighting a fire.”

Recommended for you

Black Death

The city-state of Sparta in ancient Greece was renowned for its military might; its powerful and well-trained army of professional soldiers was able to utterly vanquish rival Athens in the second Peloponnesian War (431–404 BCE). Spartan boys began preparing for war with rigorous military training as early as age 7, but nothing could have adequately prepared them for a routine component of their daily chow: black soup, aka black broth, which was made from boiled pigs’ legs, blood, salt, and vinegar. Legend has it that on tasting the soup, a man from Sybaris, a city in southern Italy known as the capital of gluttony, said, “Now I know why the Spartans do not fear death.”

Where’s the Beef?

In the waning days of the 19th century, British cavalry troops dispatched to fight the Boer War, in South Africa, were soon so short of provisions that they were forced to slaughter their horses for food, often making a meat soup called “chervil” (unrelated to the herb of the same name) and a pasty fashioned from boiled horse flesh and jelly. But the remains of their trusty mounts may not have been the worst meals these Brits were forced to endure. Maconochie Brothers, a company in Fraserburgh, Scotland, won a contract to supply the troops with a canned beef stew—made largely of sliced carrots, potatoes, onions, beans, and sometimes turnips—swimming in a thin, soup-like gravy. (Maconochie stew was also a staple for British troops in World War I.) The small tins were meant to be heated in boiling water, but that was rarely feasible on the battlefield. When cold, the “Maconochie Army Ration” was typically laden with chunks of congealed fat. It not only tasted bad (one reporter labeled it “an inferior grade of garbage”), but caused a kind of flatulence that made being in close quarters with comrades a truly memorable experience.

Flour Power

During the winter of 1777–1778, the Revolutionary War troops under the command of General George Washington at Valley Forge, Pennsylvania, were forced to endure a host of miserable conditions, most notably a critical lack of shoes, blankets, and clothing substantial enough to shield them from the rain and cold. And then there was the food: With few provisions to feed some 10,000 soldiers, the main meal was often firecake—a doughy, bread-like mixture of flour and water, flattened into dense patties, that was baked on a rock in or near a campfire until blackened. The dietary staple was so utterly tasteless that the soldiers hoped that ashes from the fire might add a little flavor.

Logan’s Runs

In the spring of 1937, Colonel Paul Logan, the deputy director of the subsistence division of the U.S. Army’s Office of the Quartermaster General, asked executives of the Hershey Chocolate Company to develop a chocolate bar that would not only provide soldiers with a high-energy field ration but withstand tropical temperatures and only taste, he said, “a little better than a boiled potato,” so that soldiers would reserve them for emergencies, not eat them as treats or trade them for cigarettes or other provisions. A few months later, Hershey unveiled Field Ration D—a 4-ounce, 600-calorie bar with a small-print warning on the package noting that it was “to be eaten slowly (in about a half hour).” Some 3 billion of the specially formulated foil-wrapped “Logan bars,” as they came to be known—made from chocolate, sugar, skim milk powder, cocoa fat, oat flour, and artificial flavoring—were produced from 1940 to 1945. But soon came countless complaints from GIs, as the unpalatable little rations were hard enough to bust a tooth and could wreak such intestinal havoc that soldiers called them “Hitler’s secret weapon.”

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

Bully for You

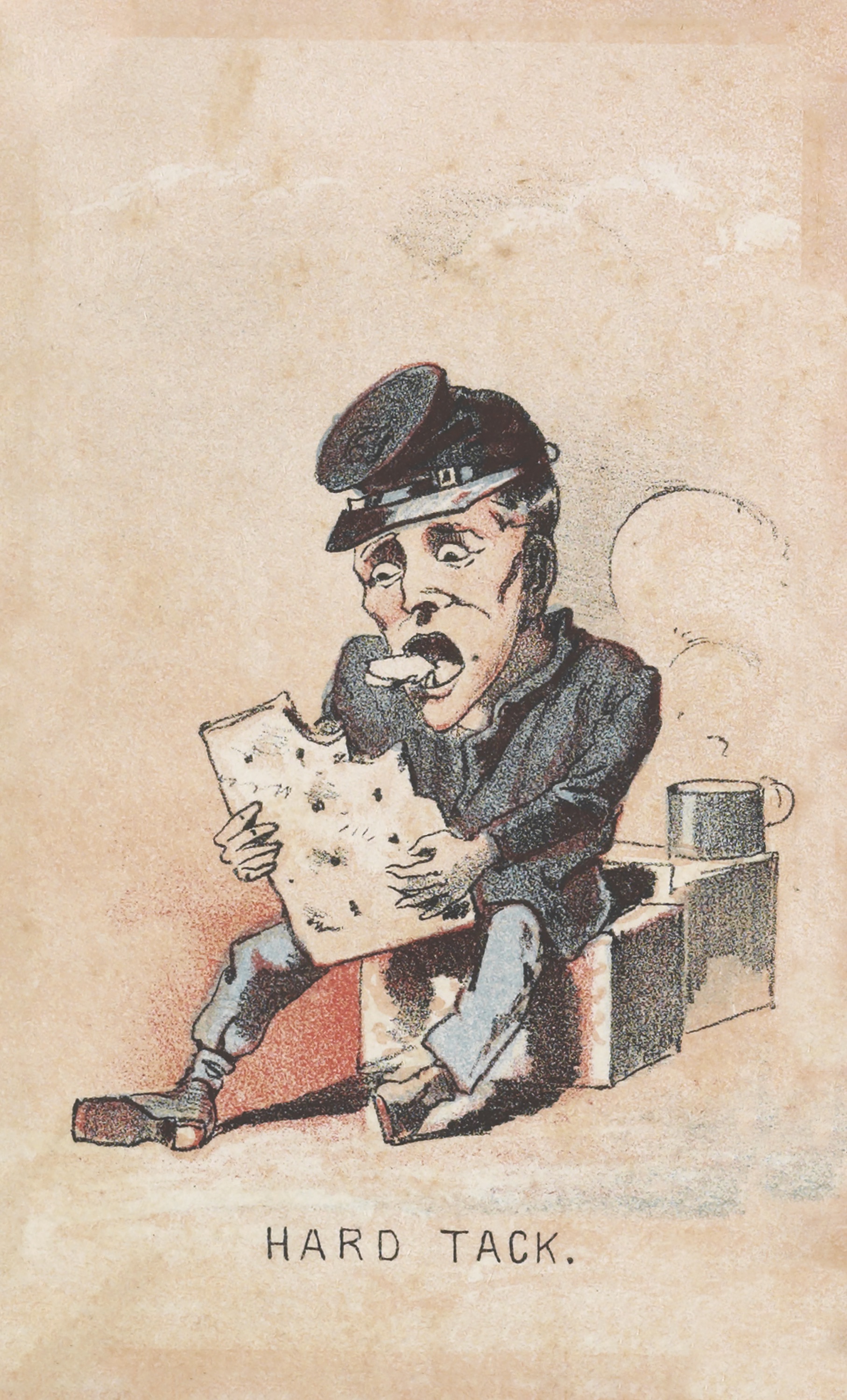

Feeding the 2.3 million British troops stationed on the Western Front in World War I was a tall order, but when members of the Royal Army Service Corps couldn’t procure fresh meat and vegetables they would dole out Maconochie stew and two other unappetizing standbys of trench cuisine: 12-ounce tins of Bully beef—a universally reviled paste of overly salty, minced corned beef held together with gelatin—and hardtack biscuits, which had fed ancient armies. Like the troops in the American Civil War, British soldiers hoping to eat the tasteless flour-and-water biscuits resorted to smashing them with a large stone or rifle butt and then soaking the broken bits in water or coffee for days. But the Brits were apparently spared the final indignity suffered by their U.S. counterparts, whose hardtack biscuits were so routinely infested with maggots and other insects that the soldiers dubbed them “worm castles.”

SOS

The Manual for Army Cooks, published in 1910 under the direction of the U.S. Army’s Commissary General, offered detailed instructions for preparing such culinary delights as beef brains and eggs, pigeon-and-robin potpies, and slow-baked possum (preferably stuffed with sage). But the most heralded recipe in the 185-page cooking manual was certainly the one for creamed chipped beef on toast (aka “Shit on a Shingle,” or simply “SOS”), which earned the rare distinction of being a mess-hall staple from the days of World War I straight through to Vietnam. (A saltier and creamier version first graced U.S. Navy cookbooks during World War II.) Sailors and servicemen routinely complained about the taste and creepy texture of the very salty SOS; some even branded it “Creamed Foreskins on Toast,” or CFSOT (pronounced sif-sot). But many of them actually found the dish’s warmth and creaminess—the result of lots of butter and evaporated milk—appealing, which may help explain why made-at-home versions of creamed chipped beef remain such a popular comfort food today.

Not Your Average Joe

Throughout the Civil War, Union army troops attached about as much importance to their coffee as they did to their minié balls and muzzleloaders, as the coveted brew provided them both comfort and a useful caffeine kick. But green or roasted coffee beans—an official component of the soldiers’ rations—were sometimes hard to come by, which gave rise to George Hummel’s memorable invention: Essence of Coffee, a cylindrical tin of evaporated joe infused with sugar and Borden’s condensed milk. The label boasted that the palm-sized tin would yield the equivalent of four pounds of brewed coffee and, when mixed with water, would perfectly preserve the “real taste” of the beans. But truth in labeling standards were apparently lax, as the thick, muddy sludge was so vile that soldiers typically refused to drink Hummel’s purportedly “celebrated” beverage a second time.

Done Up Like a Dog’s Dinner

Whether bellyaching about the Bully beef of World War I, the C-rations and K-rations of World War II, or the more contemporary Meals Ready-to-Eat, soldiers have routinely complained that their wartime grub either tasted like dog food or was too awful even for a dog. But in spring 2011, Russian troops serving in the eastern city of Vladivostok faced an entirely novel mess-hall revelation: Major Igor Matveyev posted photos and videos online revealing that the cans of “premium quality beef” being served to them were in fact cans of dog food plastered with bogus labels. The Interior Ministry denied Major Matveyev’s accusations, and for his troubles the determined whistle-blower was both stripped of his rank and, for abusing his office, sentenced to four-plus years in prison. It’s uncertain whether the Russian troops found the dog food better or worse than their usual rations.

You Are Who You Eat

In 881, troops loyal to Chinese rebel Huang Chao slaughtered residents of the capital city of Chang’an (present day Xi’an) and in the process set in motion the demise of the Tang dynasty—a three-century cultural renaissance that had begun in 618. Food was often scarce over the years that followed, as the fighting between Huang Chao’s men and Tang forces aiming to retake the city entirely disrupted farming in the surrounding areas. So both contingents turned to another source of protein: humans. According to Huang Wenxiong, a Taiwanese-born philosopher who wrote a detailed study of Chinese warfare, the Tang dynasty ushered in “the golden age of cannibalism in China.” In fact, he writes, Huang Chao established human-flesh processing factories, assigning a branch of his army responsibility for “the husbandry and slaughter of humans being raised for their meat.” Wenxiong goes on to point out that factories “would make enormous quantities of yanshi (salted corpse) by extracting the internal organs, packing them in salt, and drying them in the sun.” The yanshi—human jerky, basically—was then fed to the soldiers. MHQ

Alan Green is a journalist in the Washington, D.C., area.

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.