One of aviation’s meccas is Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, site of the first successful powered, fixed-wing flights by the Wright brothers. And then there is Hammondsport, N.Y., where Glenn Curtiss, another of America’s aviation trailblazers, experimented. Interesting and well-kept museums are found at both locations. Increased public interest in Curtiss and his contributions to aviation have led to a new museum in Curtiss’ hometown that is growing rapidly in popularity.

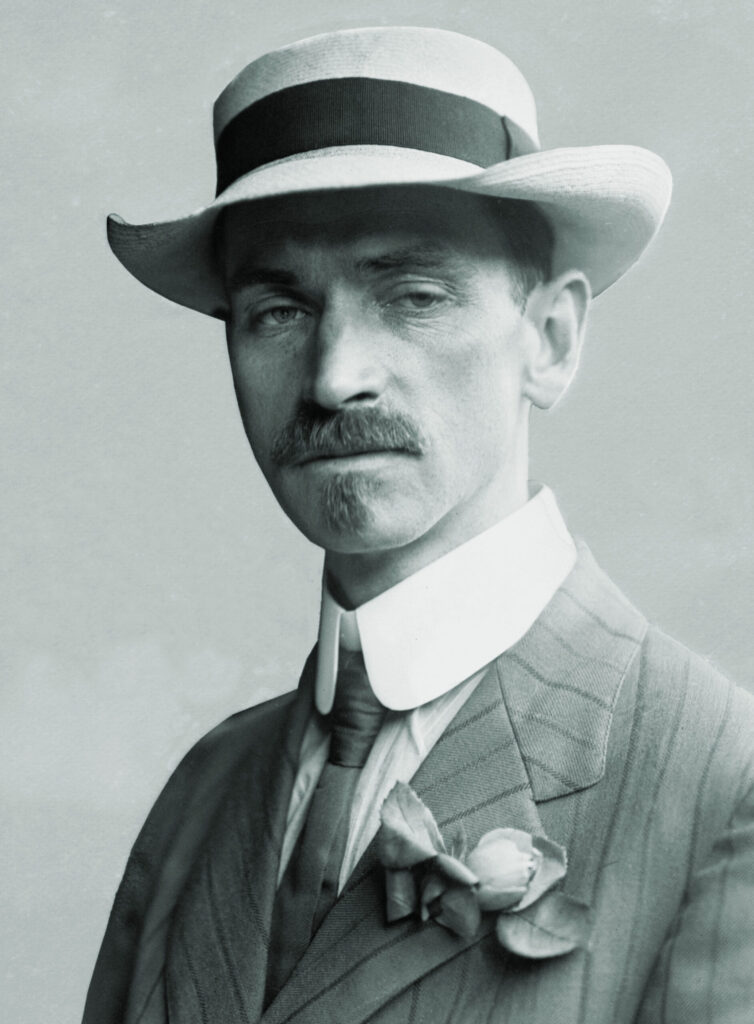

The Wright brothers made bicycles. So did Glenn Hammond Curtiss, their chief competitor, who was born in Hammondsport, at the southern tip of Keuka Lake, on May 21, 1878. His first name is derived from “the Glen,” a picturesque cleft in the hills north of the village that his mother enjoyed very much; she added an n, probably to make the name more masculine. His middle name came from town founder Lazarus Hammond.

The Wrights continued in the bike business in Dayton, Ohio, while experimenting with their planes, but Curtiss started manufacturing motorcycles. The taciturn, unsmiling Curtiss was called “the fastest man on earth” when he was clocked at 136.6 mph during a motorcycle race at Ormond Beach, Fla., in 1904. Curtiss’ entrance into flying began that same year when Thomas Scott Baldwin, famous lighter-than-air devotee, asked Curtiss to make him a two-cylinder, air-cooled engine to power his airship. The first plane Curtiss had anything to do with was Red Wing, which Casey Baldwin lofted from the ice at Keuka Lake on March 12, 1908, before a small crowd. The flight was hailed by the local press as “the first public flight by an airplane in the United States.” The Wrights contended this was untrue, as they had been flying in plain view from a field beside the trolley line linking Dayton and Springfield, Ohio, since 1904. This statement was the beginning of a feud and eventual litigation between the Wrights and Curtiss.

That the Wrights made the first powered flights has generally been accepted, but the achievements of Curtiss spanned several decades and took the airplane from its wood, fabric and wire beginnings to the forerunners of modern transport aircraft. The new museum documents his life and unique accomplishments.

Curtiss made his first flight on his 30th birthday—May 21, 1908—in White Wing, a design of the Aerial Experiment Association, a group led by Alexander Graham Bell. White Wing was the first plane in America to be controlled by ailerons instead of the wing-warping used by the Wrights. It was also the first plane on wheels this side of the Atlantic.

The first plane Curtiss built and flew was June Bug. In 1908, Curtiss won the first leg of the three-legged Scientific American magazine competition for being first to fly in a straight line for more than a kilometer. He won the next leg of the competition in 1909, for establishing a distance record. He then won the Gordon Bennett Trophy, plus the $5,000 prize, in the world’s first international air meet at Reims, France, in 1909. When the New York World newspaper offered $10,000 for the first successful flight between Albany and New York City, Curtiss won the prize money and nationwide recognition. He also won the third leg of the competition and permanent possession of the Scientific American trophy in 1910.

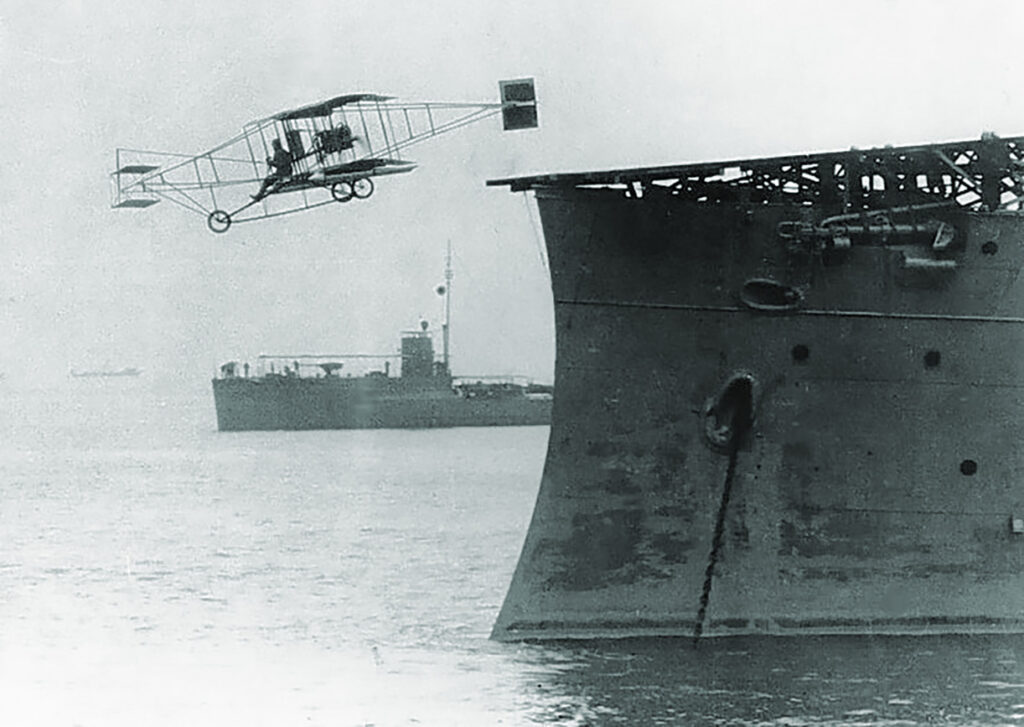

One of the major contributions to flight progress during this period was the invention of ailerons, which was the basis for the litigious rift between the Wrights and Curtiss. But Curtiss had more significant “firsts.” He deserves credit for pioneering the design of the floatplane and the flying boat. It was a Curtiss plane flown by Eugene Ely, a company exhibition pilot, that made the first successful takeoff from a Navy ship in 1910. Another Curtiss plane, the NC-4, made the first crossing of the Atlantic in 1919. Curtiss built the first U.S. Navy aircraft, called the Triad, and also trained the first two naval pilots. He received the Collier Trophy and the Aero Club Gold Medal for the greatest accomplishment in aviation during 1911.

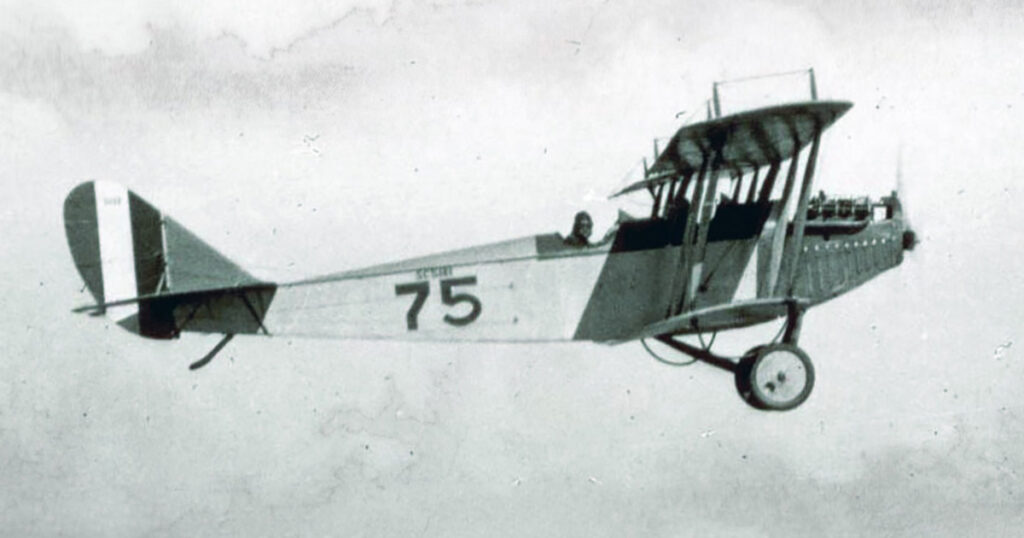

The success of the first flights of many new aircraft in those beginning days is also associated with the OX series of engines that Curtiss designed. About 12,600 of the series were built—most were installed in British, Canadian and American aircraft during World War I. It is the last of the series, the OX-5, that is best known. There was such a surplus of engines after World War I that they were sold at bargain prices by the government to many postwar aircraft manufacturers. Among those using OX-5 engines were the Laird Swallow, Travel Air 2000, Waco 9 and 10, the American Eagle, and some models of the ubiquitous Curtiss JN-4 Jenny.

In addition to a Jenny, other major aircraft on view in the Curtiss museum include precise replicas of the June Bug and Curtiss Pusher, plus an original 1919 Curtiss Oriole and 1927 Curtiss Robin. A 1907 glider is on display, as are OX engines. Also on hand is an Ohm Special, a racing plane built in 1949 by Dick Ohm and Jamie Kraph; a 1929 Mercury Chic; and a 1931 Mercury S-1 Racer.

One of the “firsts” by Curtiss that is relatively unknown was his invention of the travel trailer. An avid outdoorsman, he developed a folding tent-type trailer in 1917. A very streamlined fifth-wheel trailer was developed from this in 1919, called the Aerocar. The Curtiss four-wheeled Aerocar Motor Bungalow, or Land Yacht, evolved, which was 19 feet long, 12 feet wide and more than 7 feet high. One of these, in excellent condition, is on view and represents the forerunner of today’s house trailers.

Some of the museum space is devoted to early Hammondsport history as it relates to the inventive times in which Curtiss lived. There are collections of china dolls, cameras, radios, woodworking tools and many other antiques from the turn of the century. For restless children, there is a half-scale model of a Curtiss Pusher that they can “fly” and sit in to have their pictures taken.

The village of Hammondsport, which today still boasts a population of only about 1,000, is about five miles northeast of Bath, N.Y., and just west of the two largest Finger Lakes—Seneca and Cayuga. The town site is where Keuka Lake meets what the original settlers called Pleasant Valley. Helping to keep things pleasant today are a dozen wineries and the Greyton H. Taylor Wine Museum.

Curtiss made his last flight as a pilot in May 1930, when he flew a Curtiss Condor over the Albany/New York route. He died two months later and is buried in the Pleasant Valley Cemetery, near the scene of his first aviation triumphs.

It was not until 1928 that anyone suggested a museum be established to honor the area’s most famous resident. A local newspaper was first to suggest it; then, when Curtiss died in 1930, the idea again emerged, only to fade once more.

In 1958, local resident Otto Kohl began collecting Curtiss memorabilia. Kohl, who had been an employee of the Curtiss Aeroplane & Motor Co. in Hammondsport, began to look for a place to house the collection and was instrumental in establishing a museum in an old school building downtown. Although financial support was slow in coming, Curtiss memorabilia began to accumulate.

The Glenn H. Curtiss Museum was formally dedicated on May 18, 1963. A library and archives were established, and a request for donations of authentic Curtiss artifacts led to the acquisition of additional items for display.

Before the national bicentennial celebration in 1976, the museum underwent many changes and improvements. Exhibits were cleaned and many items in the collection were restored. A replica of the 1908 June Bug was built by volunteers and flown. When the U.S. Navy celebrated the 75th anniversary of naval aviation in 1986, a half-scale model of the A-1 Triad was dedicated, and a full-size model of a Curtiss hydro-floatplane was flown from Keuka Lake. An original 1919 Curtiss Oriole and Curtiss motorcycles (manufactured under the name Hercules) were acquired, as well as many items of local history. It was clear that new quarters had to be found to house the growing collection.

Various plans were formulated for expansion of the museum between 1978 and 1991. In 1991, a former winery was purchased, and on July 4, 1992, the new Glenn H. Curtiss Museum was opened to the public. The new facility devotes 34,000 square feet to permanent exhibits, and 2,400 square feet to temporary exhibits. The building also contains a 100-seat theater, library, archives, photographic lab, catering kitchen, a restoration shop and gift shop—all on one floor.

A $1 million fund drive was launched and completed in 1993 to fund improvements and additional display space for the museum’s growing collection of memorabilia. The number of visitors continues to grow, and it can now be said that aviation buffs have a new mecca in Hammondsport that is certainly worth the trip. Elizabeth Dann, the museum’s director, says the ultimate goal is to create the finest possible repository of Curtiss artifacts and information, and to make that part of aviation history come alive. The museum staff is well on the way to achieving that goal.