For Eddie Rickenbacker, Charles Lindbergh, Amelia Earhart and countless less famous American pilots swept up in the rise of aviation, the Curtiss JN-4 “Jenny” held a special place in their careers, if not their hearts.

After World War I, a surplus Jenny could be had for about $500, allowing many who dreamed of flying to purchase their own airplane. In an age unfettered by aviation regulations and agencies, they were free to roam America’s skies at will, barnstorming and giving rides to eager bystanders to earn a modest living.

Most people associate the Jenny with aviation pioneer Glenn H. Curtiss, but the biplane owes much of its pedigree to British designer Benjamin Douglas Thomas. The two seemed an odd couple. Curtiss had a mercurial temper at times, but was taciturn at others. A compulsive tinkerer, he would scrawl drawings of his ideas on the walls of his shop in Hammondsport, N.Y. His record of achievement was as extensive as the ongoing litigation he faced from the Wright brothers due to alleged patent infringement. Thomas, shy and self-effacing, was a trained engineer who had previously worked for both Avro and Sopwith before Curtiss lured him to the United States in 1914.

The Jenny sprang from an American desire to catch up to the aviation boom that had occurred in Europe prior to WWI. Curtiss sought to create an economical airplane that would be competitive on the world market. In 1913 he developed his first tractor biplane, the Model G. It featured a side-by-side cockpit in a fully enclosed fuselage, ailerons between the wings hinged to the interplane struts and an empennage more characteristic of European aircraft manufacturers, most notably Sopwith.

U.S. Army Signal Corps Brig. Gen. James Allen had corresponded with Curtiss in November 1912, indicating the need for a tractor biplane that met Army specifications. Curtiss told Allen that he was working on such a plane, and finally shipped the G to San Diego, where it was tested and accepted by the Army in June 1913. With an 80-hp engine, it could fly at an average speed of 55 mph and climb to 2,280 feet in 10 minutes. The G was also relatively easy to disassemble and ship, but it was only nominally successful.

The Model H followed and included some important differences—among them Farman- or Sopwith-type ailerons inset in the upper wing’s trailing edge and outboard-angled struts. Its O-type engine delivered 80-90 hp. Accepted by the Signal Corps in December 1913, the sole Model H (not to be confused with Curtiss’ line of Model H flying boats) was termed “clumsy but reliable.”

Ultimately, the G and the H were marginal performers, and both Curtiss and the Army knew it. This was likely the impetus behind Curtiss’ 1913 trip abroad to tour British and European aircraft factories. He wanted to see how they built airplanes and to lay the groundwork for foreign military contracts.

While Curtiss visited the Sopwith Aviation Company at Kingston-on-Thames, a man who was too shy to even introduce himself tagged along. Later, on a rainy London evening, both men fortuitously ducked into a newsstand on the Strand. Thomas noticed Curtiss reading a paper, and he chanced a conversation with the American aviator. He learned that Curtiss was on his way to Russia with hopes of opening a plant there. Curtiss had to make a stop in Paris before continuing to Russia, and he asked Thomas to accompany him on his dime. The Sopwith engineer readily agreed.

As they crossed the Channel, the two men discussed ideas for a new tractor biplane that Curtiss would designate the Model J. In Paris, Curtiss suggested that Thomas resign from Sopwith and work for him on the design. Thomas agreed, and soon set up a tent in his parents’ backyard where he worked feverishly to lay out the J’s design. He drew up plans, made stress and materials calculations and set specifications, pedaling his bike 20 miles roundtrip every time he had blueprints to send off to Hammondsport.

On the other side of the Pond, the blueprints were quickly turned into finished airplane components. Finally, in April 1914, Thomas received a short but sweet cable from Curtiss that simply said, “Come on over.” By early May, Thomas was in New York, never to return to England. Curtiss was pleased to have a British designer on his team in Hammondsport. Thomas could not only help him develop competitive tractor biplanes, but also aid in securing British contracts—it certainly wouldn’t hurt to have a man who had worked for both Avro and Sopwith on the payroll.

That same year, Lieutenant Benjamin D. Foulois took command of the Signal Corps’ 1st Aero Squadron. He standardized aircraft specifications, maintenance and supply. Foulois and the aviators at the Signal Corps Aviation School developed very specific guidelines for a standard squadron airplane: “a two-seat tractor biplane with a dual control system, a minimum speed of 40 mph, and a flying duration of four hours at top speed. The design had to be streamlined and include frictionless controls, a positive driven fuel pump, and a tachometer…the engine had to be easily replaced. Finally, four mechanics had to be able to assemble an airplane in two hours and disassemble and pack it away in one-and-a-half hours.”

Tractor biplanes were on the rise in Europe because of repeated fatal training accidents with pushers in which the pilot was sandwiched between the engine and the ground in a crash. By February 1914, the Army had officially condemned pusher-type aircraft. Two months later, the Curtiss J was ready for testing. With war clouds looming, the timing could not have been better—war meant military contracts.

Recommended for you

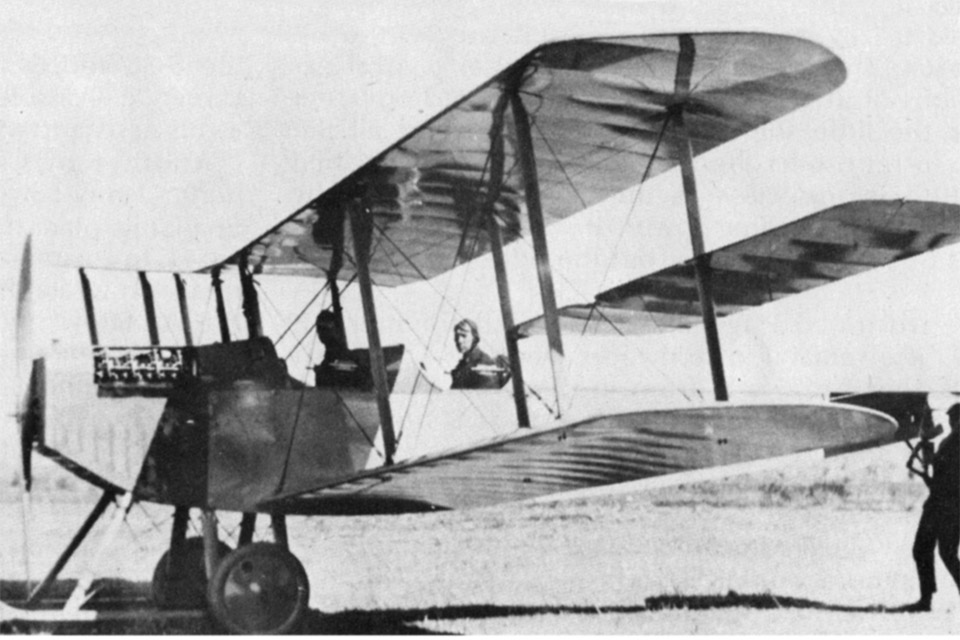

A visual overview of the Curtiss J reveals the influence of Thomas’ hand, including tandem seating and ailerons attached to the top wing trailing edge. The landing skid, designed to prevent nose-overs, is found on Avro and Sopwith aircraft. Soon after Thomas arrived at Hammondsport, he worked with Curtiss to develop the Model N. As on the J, its interplane and cabane struts were raked slightly forward—a common feature of Sopwith aircraft—though Curtiss evidently insisted that is also include his outmoded interplane ailerons.

Thomas claimed the N was a reworked iteration of the J, with the same fuselage. Only one was delivered to the Signal Corps in December 1914 out of an order of eight, and it too performed marginally. It had a 100-hp OXX engine, with the wings set at 0 degrees incidence to attain the required speed. In one of the more important design modifications, two of the vertical struts that formed the box girder fuselage were extended to become the cabane struts that secured the upper wing to the fuselage.

The JN series (1-4) was a hybridization of the J and the N, combining the best aspects of each and eventually earning the airplane its iconic Jenny nickname. Apparently this marriage of the two models soured Thomas’ working relationship with Curtiss, finally compelling him to resign. He evidently felt that Curtiss was taking too much credit for the JN, which Thomas considered largely his design. Curtiss’ method of communicating ideas by scrawling drawings on the walls was also too much for him, and the American’s temper didn’t help matters.

By this time, however, Curtiss’ gamble had already paid off. Officials from foreign governments descended on Hammondsport seeking military contracts, and the town was transformed almost overnight into a paramilitary community, with augmented security around the Curtiss factory. The response from Britain was so great that Curtiss opened a second factory in Buffalo, N.Y., to handle the demand. The Wall Street Journal reported that in the fiscal year ending October 31, 1915, the Curtiss Aeroplane Company produced more than $6 million in aircraft and engines, mainly for Britain. In December of the same year, Curtiss landed a $15 million contract from the British government.

Only a handful of JN-1s were built, and Curtiss moved swiftly to the JN-2, which featured two wings of equal span and the old shoulder-yoke method of aileron control (for both wings) found on his early pushers. The JN-2 was somewhat unstable due to an inadequate power-to-weight ratio and an overly sensitive rudder. That problem was remedied in the JN-3, whose shorter-span bottom wing and ailerons on the upper wing only were most likely inspired by the French. The yoke was replaced with a wheel, and the rudder was actuated by a foot-operated bar.

Eight JN-3s equipped the 1st Aero Squadron when Captain Foulois led it into Mexico in March 1916 as part of Brig. Gen. John J. Pershing’s punitive expedition against Pancho Villa. In contrast to the agile fighters then in combat over Europe, the JN-3’s role was primarily observation and communication. However, the squadron did conduct some experiments in bombardment and the use of machine guns. The JN-3s were still underpowered and unable to climb over Mexico’s Sierra Madres. Due to various mishaps and frustrations over aircraft, logistics and other problems, Foulois left the 1st Aero in September 1916.

By December, Curtiss had introduced the JN-4 and a Canadian-built version known as the “Canuck” to fill orders from the U.S. Army and the Royal Flying Corps in Canada, respectively. The Canuck differed from the American version in that it had four ailerons, differently shaped wings and empennage, and was also lighter. With its dual cockpits and controls and 90-hp Curtiss OX-5 V8 engine, the JN-4 was ideally suited for pilot training.

Introduced in June 1917, the JN-4D incorporated some important improvements. The control wheel was eliminated in favor of the now-standard control stick; it had ailerons on the upper wing only, giving it a more docile roll rate; and curved cutouts on the inner trailing edges of all four wing panels provided easier cockpit entry and egress as well as improved visibility. For these reasons, the JN-4D was the most widely accepted of the early variants. The U.S. finally had a trainer good enough to be mass-produced, and with the war now on and demand exceeding supply, production shifted into high gear. The need for a reliable biplane trainer was so great that the U.S. Army Air Service leveraged Curtiss to license JN-4D production to six other American companies.

The USAS desired a trainer to bridge the gap between the JN-4D and pursuit/fighter aircraft, which was the genesis of the JN-4H. It featured a 150-hp Hispano-Suiza engine (built in the U.S. under license by Wright Aeronautical), a more robust airframe, an enlarged nose radiator, ailerons on both wings and an upper-wing fuel tank that increased fuel capacity from 21 to 31 gallons. The JN-4H’s top speed was about 80 mph, with a 175-mile range and ceiling around 11,000 feet.

After the war, the U.S. suddenly had hundreds of surplus Jennies it didn’t need. Often employed as mailplanes in the early days of U.S. airmail service beginning in 1918, the Jenny carried slightly less than 300 pounds of mail in a redesigned front seat compartment (see “The Suicide Club,” May 2017).

Although Charles Lindbergh bought and soloed in a JN-4D in 1923, he trained in the JN-4H when he joined the USAS in 1924. Lindbergh had this to say about it: “…[I]t is doubtful whether a better training ship will ever be built….Jennies were underpowered…somewhat tricky…splintered badly when they crashed…but when a cadet learned to fly one…he was just about capable of flying anything on wings with a reasonable degree of safety.”

The period from 1920 to 1926 was known as the “Jenny Era,” when countless military pilots and others who first learned to fly in a Jenny purchased converted Army-surplus JN-4s and embarked on careers as barnstormers. The Jenny, along with the Standard J-1, was a reasonable stunt plane, and provided a great platform for wing-walking due to its slow speed and numerous struts and wires to hang on to. Many people nationwide got their first taste of flying in a Jenny, thus familiarizing them with aviation and promoting it as a viable form of transportation. The Jenny’s slow, easy motion made it the perfect airplane to ease an apprehensive public into the air.

The end of the Jenny Era came in 1927, when new regulations for airworthiness, maintenance and pilot licensing requirements were implemented—regulations that the Jenny could not meet. By 1930 it was illegal to fly a Jenny in most of the U.S. The vintage airplane movement of the 1950s revived interest in the type, and today Jennies operate under experimental aircraft license status.

Glenn Curtiss’ calculated gamble to co-opt a gifted British designer to help him launch his tractor biplanes into the global market had paid off. The JN-4 was one of the most successful aircraft of its day, and launched the careers of many aviation luminaries. Subject to Curtiss’ constant tinkering, the JN-4 series spawned variants from A to S. It formed the cornerstone of the U.S. military aviation training program, as well as various flight training schools abroad. After the war, it spurred the first U.S. airmail service and ushered in the barnstorming age. The bitter dividend created by its genesis was the dissolution of the partnership that had made the Jenny possible.

Mark C. Wilkins is a historian, writer and museum professional who is currently working on three books about World War I. Recommended reading: Curtiss: The Hammondsport Era, 1907-1915, by Louis S. Casey; Jenny Was No Lady: The Story of the JN-4D, by Jack R. Lincke; and Curtiss Aircraft, 1907-1947, by Peter Bowers.

Genesis of the Jenny appeared in the July 2017 issue of Aviation History Magazine. Subscribe today!