James Wilkinson served as commanding general of the U.S. Army under the first four presidents—all the while engaging in a treasonous intrigue with Spain

During its fight for independence from Great Britain, and through its early days as a sovereign nation, the United States of America was blessed with a surfeit of extraordinary men. Brilliant statesmen, futurists, deep and creative thinkers, they paved the way for a grand experiment in personal liberty that became the envy of the world.

It is safe to say James Wilkinson was not among those luminaries. He was, in fact, a consummate rogue and self-aggrandizing, avaricious provocateur whose actions bordered on—and frequently embraced—espionage and treason, threatening the very well-being of his country. In his 1889 book The Winning of the West future president Theodore Roosevelt wrote of Wilkinson, “In all our history there is no more despicable character.” Yet Wilkinson served his nation’s first four presidents, occupying elevated positions in the military, state and federal hierarchies. And despite being the subject of repeated congressional inquiries and at least two courts-martial, he never saw the inside of a jail cell.

Biographers surmise Wilkinson’s troubles in part revolved around a fixation on money rooted in his youth. He was born in Calvert County, Md., in 1757, the second of four children born to a respectable but failed planter. By the time James came along, the family plantation was heavily mortgaged. When he was 6 years old, his father died, and the estate was broken up, leaving the family without support. The lack of financial resources left a permanent impression on the young Wilkinson, who had to rely on the kindness of wealthy relatives to further his education and cover the cost of medical school in Philadelphia.

In April 1775 the impatient 18-year-old decided two years of advanced study were sufficient, and he laid plans to return to Maryland and practice medicine. Just before Wilkinson left Philadelphia, however, the worrisome news came that disgruntled colonists had engaged British troops at Lexington and Concord, Mass., commencing the American Revolutionary War.

The prospect of war fired the young physician’s sense of adventure, and he began drilling with a local militia unit. In his autobiography he admits having been in complete ignorance of the rebel cause. “My youth had not allowed me time or means to investigate the merits of the controversy,” he wrote. “It was, in truth, an impulse which characterized the times.” His enthusiasm stemmed less from a sense of patriotic fervor than a preoccupation with the trappings of war itself. While in Philadelphia he had watched in fascination as red-coated troops conducted crisp exercises on a parade ground. “I was struck with the idea of a painted wall, broken in pieces and put in motion,” he later wrote. “It appeared like enchantment, and my bosom throbbed with delight.…From that day I felt the strongest inclinations to military life.” Weeks after joining the militia, Wilkinson learned of the Battle of Bunker Hill. Weary of waiting for the war to come to him, he quit his practice, traveled to Boston and joined the month-old Continental Army.

The Army was in its formative stages, and Gen. George Washington stood in desperate need of good officers. Wilkinson was a born charmer; even a sworn enemy once referred to him as “easy, polite and gracious.” He had an uncanny ability to read people, and Washington became one of many beguiled by him, so much so he soon commissioned Wilkinson a captain in Col. James Reed’s newly formed 3rd New Hampshire Regiment. The ambitious young officer also served as an aide to Nathanael Greene, one of Washington’s best generals.

But Wilkinson set his sights even higher. No one in the nascent Continental Army had the dash or reputation for gallantry in action of Brig. Gen. Benedict Arnold. He was a soldier’s soldier and a favorite of Washington. Deciding to hitch his star to Arnold’s military fortunes, Wilkinson ingratiated himself and was soon appointed his aide.

Wilkinson himself was not a natural soldier. He possessed what biographer Andro Linklater refers to as “an almost theatrical vanity,” which often interfered with his judgment. But he was an expert ladder climber. By vocally supporting Washington’s measures for improving the Army and otherwise flattering his superiors, he advanced rapidly through the ranks. “There was something of the seducer in the way James Wilkinson set about winning the hearts of his generals,” Linklater notes.

Calculating though Wilkinson was, he apparently developed a true admiration and affection for Brig. Gen. Horatio Gates, adjutant general of the Army. The young officer later attributed his strong feeling for Gates to “his indulgence of my self love.” Wilkinson promptly set out to woo him as he had Greene and Arnold. Gates took to the young man, naming him his chief of staff.

Those were heady times for young Wilkinson. He accompanied Washington in the historic attack on Trenton, for which the commander in chief promoted him to lieutenant colonel. Meanwhile, Gates made Wilkinson his deputy adjutant general. Apparently, Gates also had a driving ego. Through his plotting, overweening ambition and politicking he had forever alienated Arnold and Northern Department commander Maj. Gen. Philip Schuyler. And when Gates—a good organizer but poor field officer—shamelessly took credit for the Continental victory at Saratoga, despite Arnold’s decisive actions in defiance of his commander, Wilkinson sided with Gates, betraying his former friend and mentor.

His misdirected loyalty paid dividends. In November 1777, through Gates’ influence, 20-year-old Wilkinson—who had yet to lead troops in battle—was promoted to brevet brigadier general over the heads of several more deserving officers. And when Congress appointed Gates president of the newly created Board of War, the general managed to get Wilkinson appointed board secretary.

The bond between Wilkinson and his then benefactor, however, soon devolved into a mutual hatred that impelled them to the field of honor. The trouble began when Maj. Gen. Thomas Conway, a man of questionable character whom Congress had appointed inspector general, hatched a plot to displace Washington as commander in chief and install Gates in his place. Reportedly under the influence of strong drink, and flush with his own arrogance, Wilkinson—who, along with Gates, was deeply involved in the plot—carelessly revealed the details to dinner companions, one of whom was a highly placed supporter of Washington. When the commander in chief exposed the “Conway Cabal,” the conspiracy foundered, and Conway ultimately resigned in disgrace. When later questioned about the leak by an irate Gates, Wilkinson tried to deflect blame onto an unsuspecting friend and fellow officer, but his betrayal came to light. Gates and his former acolyte exchanged harshly worded missives and arranged to meet across pistols. Nothing came of the affray outside of a deep and lasting enmity.

With the shadow of the Conway debacle hanging over him, Wilkinson resigned both his commission and his position on the Board of War. As usual he landed on his feet. On Nov. 12, 1778, he entered into a favorable marriage with Philadelphia socialite Ann Biddle, with whom he would have four sons. In July 1779 he accepted congressional appointment to the post of clothier general. Bored with the work and dissatisfied as always with the pay, he resigned less than a year later.

After leaving the Army, Wilkinson dabbled in politics, serving two consecutive terms in the Pennsylvania General Assembly, and kept his hand in military matters as a brigadier in the state militia. Seeking still greener pastures, in 1784 he moved to the raw and roiling Virginia frontier district of Kentucky, where he lobbied for statehood, tried his hand at land speculation and sold general merchandise. No legitimate venture seemed to fill his coffers, however, so in 1787 he secretly established contact with the Spanish government and turned his hand to treason.

At the time war with Spain was an ever-present possibility, one the war-weary United States would do well to avoid. Spain controlled three times as much territory in North America as did the United States and was determined to prevent the new nation from spreading its wings westward. King Carlos IV had earlier banned all foreigners from trading on the Mississippi River. Negotiating through Esteban Rodríguez Miró, governor of the sprawling Spanish territory of Louisiana, Wilkinson convinced the monarchy that if he were he granted a trade monopoly with New Orleans, the capital of colonial Louisiana, he would work in Spain’s interests to discourage further Anglo expansion. The monopoly was granted, and to cement the agreement, Wilkinson signed a declaration of allegiance to the king of Spain. For the next few years the turncoat merchant carried on a lucrative trade. He also attempted—unsuccessfully—to sway Kentuckians’ loyalties away from the United States and to Spain.

Despite his unfair trading advantage, Wilkinson proved both inept and unlucky in business. As treason proved more lucrative, he ultimately expanded his deal with Spain into a decades-long career of espionage. Outwardly, the arrangement was simple; he sold American secrets to the Spaniards for silver. It required, however, meticulous attention to detail, especially considering the information had to pass through various hands in New Orleans and Mexico before arriving in Spain. At a time when the powerful monarchy was vying with the fledgling United States for primacy in North America, Wilkinson managed to walk a fine line between the rival nations.

The spy and his Spanish masters communicated using an elaborate cipher code-named No. 13, and the Spanish took to calling their American agent by that name. As long as the code remained unbroken—which it did—his treason could not be proven. Still, Wilkinson lived in constant fear of discovery. One of his major worries centered on the delivery of his payoffs from Spain. They were conveyed by messenger aboard river vessels in the form of silver dollars, which were cumbersome and difficult to conceal. To muffle the noise during transport, he had them packed in barrels of coffee or casks of rum. He also kept a file of forged and false documents, should authorities intervene.

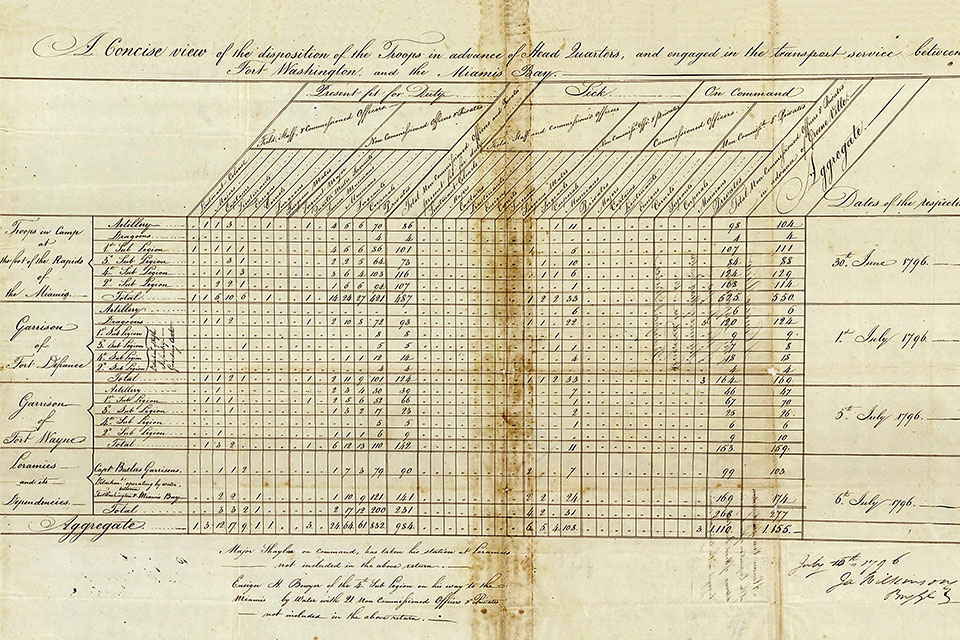

of the disposition of troops at Forts Wayne and Defiance. (Indiana Historical Society)

Wilkinson had cause for concern. On one occasion the crewmen of a boat he’d hired murdered a courier conveying a $3,000 payment to the agent. Authorities soon arrested the suspects and hauled them before a magistrate. The men immediately betrayed Wilkinson’s treasonous arrangement with Spain. However, they spoke only Spanish, and by arrangement the translator sent for was one of Wilkinson’s confederates. The translator garbled the prisoners’ statements, and the elusive spy once again narrowly escaped detection.

Wilkinson’s treasonous accomplishments were all the more stunning considering he was the commanding general of the Army during much of the time he was betraying his country.

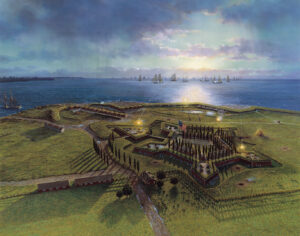

In 1791, as an Indian uprising under Miami Chief Little Turtle threatened the Kentucky frontier, Wilkinson led a force of volunteers on a series of successful punitive raids, which he quickly parlayed into a commission as lieutenant colonel of the 2nd U.S. Infantry. The next year, as President Washington presided over the reorganization of the Army as the Legion of the United States, he appointed Maj. Gen. Anthony Wayne commander and Wilkinson as his second with the rank of brigadier general. After Wayne’s untimely death from illness in 1796, Wilkinson succeeded him as the Army’s senior officer. On a personal appeal from President John Adams, Washington himself resumed command in 1798 as tensions with France heated up. But in 1801, under President Thomas Jefferson, Wilkinson again assumed command of the Army. By that time Spain had paid him $32,000—equivalent to nearly $600,000 today—for his services, which included sharing the military plans and troop movements of the very Army he was commanding.

Three years later when Jefferson sent Meriwether Lewis and William Clark on an ostensibly scientific overland expedition to the Pacific Ocean, Wilkinson immediately informed the Spanish of the explorers’ true purpose—to map and establish an American presence in the newly acquired territory. In an act of open treason Wilkinson advised Spain to “detach a sufficient body of chasseurs to intercept Capt. Lewis and his party.” Thankfully, the Spanish were unable to find the explorers. Had they succeeded, Lewis and Clark might have vanished, both in person and from the history books. For his infamy Wilkinson was paid $12,000 and given an annual trade deal with Havana.

In 1805—the very year Jefferson appointed him first governor of Louisiana Territory—Wilkinson expanded his repertoire as a traitor through collaboration with former U.S. Vice President Aaron Burr. Burr reportedly planned to seize control of large swaths of land in the North American interior and establish an independent country. To achieve his goal, he’d formed a cabal of Army officers, statesmen and wealthy planters, and he tapped Wilkinson to command the invasion force.

Burr’s trust was misplaced, however, for Wilkinson—dubious of Burr’s success and fearing discovery of his own treason—informed Jefferson of the conspiracy. In a series of letters to the president he revealed details of the plot, denied any personal involvement and later proffered proof of Burr’s treason—an unsigned, coded letter, allegedly written by Burr and sent to Wilkinson, that revealed the former’s plans. In early 1807 Jefferson had his former vice president arrested and tried for treason.

Despite the fact Wilkinson was the star prosecution witness, it soon became evident the general had reworked the letter in order to clear himself and incriminate Burr. Chief Justice John Marshall also ruled that while the defendant had shown intent to commit treason, he had committed no overt act of war. The jury acquitted Burr. His reputation and prospects in shambles, the disgraced statesman fled to Europe.

Wilkinson narrowly escaped indictment on charges of misprision of treason for having failed to expose the plot sooner. He did not get away unscathed, however. Jefferson had him removed as territorial governor. His public image—long mired in rumor and suspicion—further suffered. Although unable to indict Wilkinson, jury foreman and renowned statesman John Randolph pilloried the general as a “mammoth of iniquity…the only man that I ever saw who was from the bark to the very core a villain.” Congress launched two inquiries into Wilkinson’s affairs. Predictably, it was unable to prove anything.

In 1811 Jefferson’s successor, President James Madison—who harbored deep-rooted suspicions of Wilkinson’s loyalty—ordered a military court of inquiry. Again, in the absence of hard evidence, Wilkinson was exonerated.

At the outbreak of the War of 1812, despite the persistent rumors of espionage, the shadow of the Burr trial, his near indictment and Madison’s military court, Wilkinson was promoted to major general. He proved a poor battlefield commander, however, and his defeats prompted yet another military inquiry. Though relieved of command, he was yet again cleared. Honorably discharged in 1815, Wilkinson left the Army, in the words of military historian Robert Leckie, “an officer renowned for never having won a battle or lost a court-martial.”

Wilkinson’s career in treason simply dried up, as did his funds. Desperately in need of a fresh start, and envisioning himself an ideal adviser to Emperor Agustín of a newly independent Mexico, the 65-year-old American sailed for Veracruz in 1822. His plans fell apart when the emperor abdicated the following year. On Dec. 28, 1825, having grown increasingly ill and devoid of both money and influence, Wilkinson died in Mexico City.

It remains a mystery why America’s first three presidents placed their confidence in such a dedicated rogue as Wilkinson. Certainly they had all heard the public rumblings about his treachery, which could not be dismissed as simple gossip or rumormongering. Over the years, despite Wilkinson’s best precautions, suspicion had spread, prompting a steady stream of accusations in the form of pamphlets, letters to Congress, public addresses, even a newspaper (Kentucky’s Western World) obsessed with “outing” him. He came under the scrutiny of numerous Congressional investigations and courts-martial. Although none produced definitive proof of his treason, the stench of corruption lingered about him.

“Unless a collective blindness was at work,” biographer Linklater posits, “his political contemporaries found in him some other quality that outweighed suspicions about his loyalty.” The main reason his superiors retained Wilkinson as commander of the Army, Linklater argues, was to ensure soldiers’ loyalty at a time when many viewed a standing Army as a potential threat to the republic. “Successive administrations gambled that the general’s influence in taming the Army would outweigh the risk of his tendency to treachery.” Still, it begs the question, Couldn’t a competent commander of proven loyalty have served the same function? Ultimately, it is an enigma as indecipherable as the code used by agent No. 13.

Few historians question the extent or depth of Wilkinson’s treachery. For one, he was an obsessive and self-centered writer, and in addition to his self-justifying 1816 autobiography, Memoirs of My Own Times, he wrote and received countless letters over his lifetime, many of which are clearly incriminating. Several thousand additional documents—official reports, military orders, court transcripts, contemporary news articles and personal correspondence—also point to his duplicitous conduct. Among other evidence, a cache of papers detailing many of his activities turned up in Baton Rouge in the late 1800s. More recently, historians poring over government archives in Madrid and Mexico have unearthed signed documents in Wilkinson’s hand, confirming his espionage. In one missive he advises the Spanish government to settle Texas with “good Catholics,” lest it become “a haven of pirates and murderers.” Another document details the tens of thousands of silver dollars paid to Wilkinson for his services to Spain.

Throughout his life Wilkinson lied, cheated and plotted, all the while charming his way out of personal jeopardy. So skilled a manipulator was he that to this day it is often impossible to separate fact from innuendo. Nonetheless, dedicated researchers have irrefutably established that throughout his life Wilkinson acted chiefly for his own financial betterment. Utterly devoid of conscience, he didn’t hesitate to betray supporters or accept remuneration from a hostile foreign government for the betrayal of his country.

In a 1905 treatise frontier historian Frederick Jackson Turner offered the quintessential summary of Wilkinson’s character, deeming him “the most consummate artist in treason that the nation ever possessed.”

For further reading frequent contributor Ron Soodalter recommends Tarnished Warrior: Major General James Wilkinson, by James Ripley Jacobs; An Artist in Treason: The Extraordinary Double Life of General James Wilkinson, by Andro Linklater; and General James Wilkinson, by Robert Grey Reynolds Jr.