I shall sup tonight in Baltimore—or in Hell!” Thus spoke British Maj. Gen. Robert Ross, who commanded His Majesty George III’s land forces opposite the nascent United States’ third largest city on Sept. 12, 1814. It was no mere boast, as just three weeks earlier the redoubtable Irish warrior, supported by Rear Adm. George Cockburn, had routed the American army at Bladensburg, Md., and torched federal buildings (including the White House) in the capital at Washington, D.C.—surely the most shameful humiliation in U.S. history. Whether or not Ross supped in Perdition that September night, two sharpshooting leatherwork apprentices serving in the Maryland militia, Daniel Wells and Henry McComas, enshrined as the “Boy Heroes of North Point,” ensured Ross did not eat in Baltimore or anywhere else this side of Hell ever again.

During the American Revolutionary War wary Patriots constructed a small earthwork at Whetstone Point, the tip of a peninsula flanking the entrance to Baltimore Harbor. In 1794, recognizing the importance of safeguarding that major port, President George Washington persuaded Congress to appropriate funds for a 20-gun battery and small redoubt at the point. After the 1798 outbreak of the Quasi-War with France work continued on a new brick-and-masonry structure, complete with a magazine and barracks. Its defenders named it after Irish-born Baltimorean James McHenry, Washington’s secretary of war. The garrison became increasingly crucial after the United States declared war against Great Britain on June 18, 1812, in protest of the Royal Navy’s seizure of American trading ships and impressment of sailors as the “by any means necessary” British battled the existential threat of Napoléonic France.

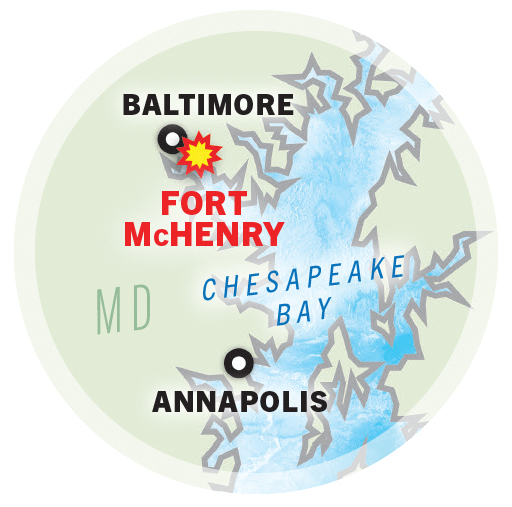

In 1813 the British launched a widespread terror campaign in the Chesapeake Bay, landing marines, sailors and soldiers across the region to raid and pillage. After burning Washington, the British set their sights on Baltimore. Under the adept leadership of Samuel Smith, however, the city proved a difficult nut to crack. Smith, a 62-year-old American Revolutionary War veteran and major general of the Maryland militia, organized defenses and constantly drilled his troops. In September the British landed nearly 5,000 men under Ross and Cockburn northeast of the city. However, after the subsequent Battle of North Point, where Ross fell, they were rebuffed at the city’s earthworks, manned by at least 10,000 American Regulars and 100 cannons. It appeared the British would need the Royal Navy to enter Baltimore Harbor in support of the attack. But Fort McHenry and its 1,000 defenders blocked the way and would have to be eliminated.

On Sept. 13, 1814, a Royal Navy fleet, spearheaded by five bomb ships and a sloop equipped with rocket launchers, commenced a bombardment of Fort McHenry, hurling upward of 1,500 shells at the garrison over the next 25 hours. When the fog and smoke cleared at “dawn’s early light” the next morning, Fort McHenry and its defenders were still there, having resisted British landing attempts and the storm of shot and shell at the cost of only four dead. Flying “o’er the ramparts” was the inspiring symbol of their victory—a 30-by-42-foot American flag (the Stars and Stripes) made the previous year by Baltimorean widow Mary Young Pickersgill at the request of fort commandant Major George Armistead. Francis Scott Key, an American attorney who’d been temporarily detained aboard a British ship in the outer harbor, witnessed the bombardment and was inspired to write a poem he called “Defense of Fort M’Henry,” later put to the music of a British drinking song and renamed “The Star-Spangled Banner.”

After the War of 1812 Fort McHenry was upgraded, with expanded buildings and additional outer defenses. Supporting it was nearby Fort Carroll, designed and constructed by Army engineer Robert E. Lee. During the Civil War Fort McHenry was a prison for both captured Confederate soldiers and pro-Southern Marylanders held after President Abraham Lincoln suspended habeas corpus. Serving as prison chaplain was Father James Gibbons, future founding chancellor of Washington’s Catholic University and archbishop of Baltimore. The fort declined in strategic importance in subsequent decades, though its grounds hosted a sprawling Army hospital during and after World War I. In 1931 Congress adopted “The Star-Spangled Banner’ as the national anthem, in turn prioritizing the preservation of Fort McHenry, whose upkeep was transferred to the National Park Service. In 1939 it was designated a national monument and historic shrine, the only one of the more than 400 existing NPS units.

This story appeared in the Winter 2024 issue of Military History magazine.

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.