On September 1, 1814, after the British had left the city of Washington in flames, the noted D.C. lawyer Francis Scott Key rode from his stately home in Georgetown to the White House. Key, 35, came to the torched presidential mansion to ask permission to undertake a delicate mission involving a longtime family friend, Dr. William Beanes, a prominent local surgeon.

A few days earlier, British troops had raided several farms just east of Washington, including Beanes’. The physician then organized a posse that captured several British soldiers and threw them in a local jail. One escaped and returned with company the next night, August 28, capturing Beanes and two other Americans—Dr. William Hill and Philip Weems. The men were rousted from their beds at midnight and forced to ride 35 miles to Benedict in southern Maryland, where the British were about to embark for Baltimore. Hill and Weems were released, but the 65-year-old Beanes was put aboard the Tonnant, Vice Admiral Alexander Cochrane’s flagship, and the fleet sailed toward Baltimore.

Friends of the Beanes family tried to intervene with the British to no avail. One of them was Key’s brother-in-law Richard Williams West, who rode to Georgetown to ask the well-spoken lawyer if he could arrange Dr. Beanes’ release. Though Frank Key, as he was known to family and friends, never publicly explained why he agreed to the request, it’s likely that he wanted to assuage the shame and guilt he felt following the American military’s sad performance at Bladensburg—which he had witnessed—and its catastrophic aftermath.

Key secured permission to intercede from President James Madison and from Commissioner General of Prisons John Mason, who asked 25-year-old Army colonel John Skinner to accompany Key, since Skinner had arranged several exchanges of British naval officers. Mason also prevailed upon the senior British prisoner in Washington, Colonel William Thornton, to have his fellow prisoners write letters describing their humane treatment. Key collected the letters before he left.

Key explained the mission in a September 2 letter he wrote to his mother from Georgetown: “I am going in the morning to Balt to proceed in a flag vessel to Gnrl [Robert] Ross. Old Dr. Beanes of Marlbro’ is taken prisoner by the Enemy, who threaten to carry him off. Some of his friends have urged me to apply for a flag [of truce] and go & try to procure his release.” In a letter to his father, Key was cautiously pessimistic: “I hope I may succeed, but I think it very doubtful.”

Key left for Baltimore on the morning of September 3. He had conflicting feelings about the vehemently anti-Federalist and pro-war people of Baltimore, about the British and about the war itself. Calling the conflict “a lump of wickedness,” Key later wrote to a friend, “sometimes when I remembered that it was [in Baltimore] the declaration of this abominable war was received with public rejoicings, I could not feel a hope that [the British] would escape.” Then again, the extremely pious Key said, when he realized that “faithful” Baltimoreans supported the war, it gave him strength to go ahead with his mission—or, as Key put it: “I could hardly feel a fear.”

In the end, feelings of antipathy for the British outweighed Key’s grudge against the Baltimore war hawks. The British, he said, were intent on burning the city, and “I was sure that if taken it would have been given up to plunder. . . . It was filled with women and children.”

Key met Skinner in Baltimore on September 4. The following day, the two men sailed under a safe-conduct flag on an American cartel ship—mostly likely the President, commanded by John Ferguson. They found the Tonnant in the early afternoon of September 7 at the mouth of the Potomac River. General Ross and Rear Admiral George Cockburn welcomed the Americans aboard and invited Key and Skinner to discuss the prisoner exchange over an early dinner.

Frank Key did not take kindly to his hosts. “Never was a man more disappointed in his expectations than I have been as to the character of the British officers,” Key later wrote. “With some exceptions, they appeared to be illiberal, ignorant and vulgar, and seem filled with a spirit of malignity against every thing American.” Then he second-guessed himself: “Perhaps, however, I saw them in unfavourable circumstances.”

Key and Skinner argued that Dr. Beanes never should have been taken prisoner, because he was a civilian noncombatant. Then they turned the letters from the British prisoners over to their hosts. That seemed to convince the British to let the doctor go—under one condition: Key, Skinner and Beanes could not return to Washington until after the attack on Baltimore.

The three Americans were escorted to the British frigate Surprize. On September 10, Key, Skinner and Beanes were allowed to return to their vessel, accompanied by British marine guards. The Surprize towed them into Baltimore Harbor, about eight miles from Fort McHenry, which protected the approach to the city from the Patapsco River. There they dropped anchor and spent the next four days aboard ship.

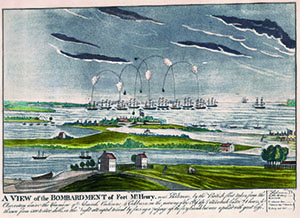

Francis Scott Key had a ringside seat during the entire Battle of Baltimore from his position a mile or two behind the British fleet. Key, Skinner and Beanes saw a large American flag flying over Fort McHenry before the British bomb ships let loose at 6:30 a.m. on September 13. All that day Key paced the deck as hundreds of rockets and bombs burst in the air. Peering though the darkness as day turned to night—at “the twilight’s last gleaming,” as he would later put it—Key could still make out the Stars and Stripes.

None of the men could sleep as the relentless British assault continued hour after hour. The air filled with hissing rockets and screaming cannonballs accompanied by the booming thunder and the flashing lightning of a torrential storm. When the British guns went silent about 3 a.m. on the 14th, the men did not know whether that meant an American victory or defeat.

As the horizon lightened, Key, Skinner and Beanes could not tell if Baltimore had survived. Rain clouds obscured the sunrise and a mist hung over the water. Even peering through their spyglasses, the Americans still could not clearly make out the fort or the British ships in what Key would immortalize as “the dawn’s early light.” Just after 6 a.m., Frank Key finally saw a flag hanging limply over the fort. But it was impossible to tell if it was the Stars and Stripes or the Union Jack. Then a slight breeze stirred and Key saw with relief that the American flag was still there.

Key later said that he felt the “warmest gratitude” when the British failed in their attack, as well as “most merciful deliverance.” As dawn broke on September 14, the prolific amateur poet poured out those feelings in four heartfelt verses written on the back of a letter he had in his pocket.

“I saw the flag of my country waving over a city,” Key said 20 years later. “I heard the sound of battle; the noise of the conflict fell upon my listening ear, and told me that ‘the brave and the free’ had met the invaders.” Through “the clouds of war, the stars of that banner still shone in my view,” he said. “Then, at the hour of deliverance and joyful triumph, my heart spoke [and I thought] ‘Does such a country—and such defenders of the country—deserve a song?’ ” With that “came an inspiration not to be resisted,” even though “it had been a hanging matter to make a song.”

Key worked on the verses while sailing back to shore and then wrote out a finished copy the next day at a hotel, most likely the Indian Queen Tavern, at Hanover and Market streets in downtown Baltimore. The following day, September 16, Key presented the verses to his brother-in-law Joseph Nicholson.

Nicholson took the verses either to the offices of the Baltimore American and Commercial Advertiser or—more likely—to Benjamin Edes’ print shop on the corner of Baltimore and Gay streets. Edes printed copies of the verses bearing the title “Defence of Fort M’Henry” on handbills and broadsheets and distributed them throughout the city. The text of the song appeared in the daily afternoon newspaper, the Baltimore Patriot and Evening Advertiser, on September 20.

The newspaper and broadsheet included a short introduction, most likely written by Nicholson. It read: “The following beautiful and animating effusion, which is destined long to outlast the occasion, and outlive the impulse which produced it, has already been extensively circulated. . . . We rejoice in an opportunity to enliven the sketch of an exploit so illustrious, with strains which so fitly celebrate it.”

The article indicated that the song was to be sung to the tune of “To Anacreon in Heaven,” an English song, popular in pubs, composed by John Stafford Smith about 1775. Very well known in the United States, the tune was the theme song of the Anacreontic Society of London, a gentlemen’s club that met periodically to listen to musical performances, dine and sing songs. The club took its name from Anacreon, the ancient Greek poet known primarily for his verses in praise of love, wine and revelry.

On September 21, the Baltimore American and Commercial Advertiser published the song. The following day “Defence of Fort M’Henry” appeared in the Federal Republican of Georgetown. The introduction said: “A friend has obligingly favored us with a copy of the following stanzas, which we offer to our readers as a specimen of native poetry, which will proudly rank among the best efforts of our national muse.”

It is believed that the song was first sung publicly on October 19, 1814, in Baltimore at the Holliday Street Theatre, popularly known as “Old Drury,” after the performance of a play. “Our good Frank’s patriotic song,” Key’s aunt Elizabeth Maynadier wrote to his mother on October 27, “is the delight of everybody.”

The effusion became known as “The Star-Spangled Banner” (from a line in the first stanza) after Carr’s music store of Baltimore first published it with that title in sheet music form in November. By 1816 word had spread throughout the young nation that Francis Scott Key of Georgetown wrote the stirring patriotic air.

The song took on added significance during the Civil War as the U.S. flag itself came to symbolize national unity. The Navy in 1889 ordered the song to be played at the morning flag-raising ceremony; the Army soon followed suit for the lowering of the colors in the evening. In the early 20th century, Congress considered more than 40 resolutions to adopt “The Star-Spangled Banner” as the national anthem. It faced stiff competition from “Yankee Doodle” and “America the Beautiful,” but the Veterans of Foreign Wars, the American Legion and various patriotic groups mounted a concerted lobbying campaign. Soprano Elsie Jorss-Reilly, a member of the VFW auxiliary, performed the song on floor of the U.S. House in February 1930 to prove that it was not “pitched too high for popular singing.” On March 3, 1931, President Herbert Hoover signed into law a measure officially naming Key’s ode to the survival of Fort McHenry and the city of Baltimore the national anthem of the United States.

This story originally appeared in the October 2014 issue of American History magazine.