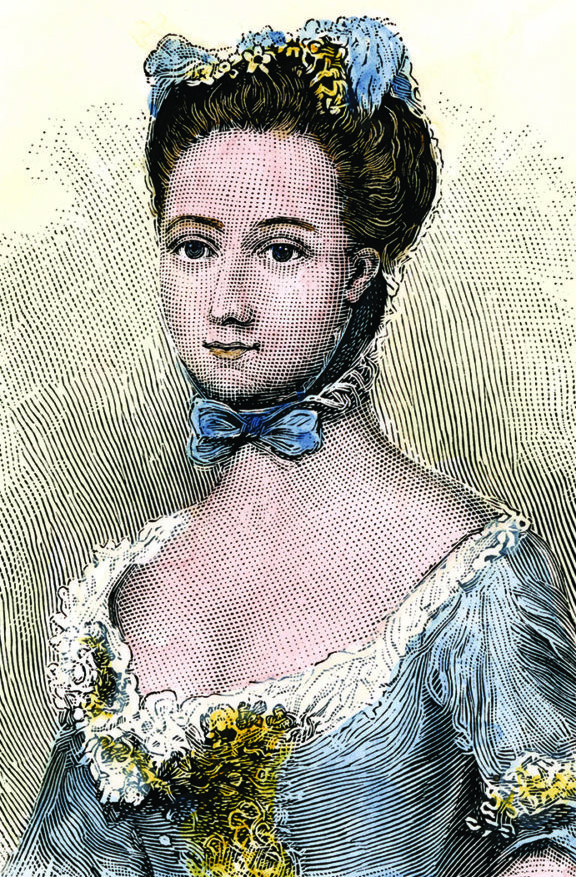

Frederika Charlotte Louise, Baroness Riedesel zu Eisenbach—better known as Baroness von Riedesel—was the wife of Baron Friedrich Adolf Riedesel, a German mercenary commander who served with the British during the American Revolutionary War. Frederika insisted on traveling with her husband and his army, and kept a diary.

Frederika fell in love with Friedrich, a seasoned Hessian officer, when he was recovering from his wounds at her family’s estate during the Seven Years’ War (1756-1763); she was 16 years old when they married. The couple enjoyed a close relationship, so much that Friedrich consented to allow his wife to follow him when he went to war in North America.

A determined woman, Frederika was not put off from the journey although she had three very young children and angered her mother by going. “I am very sorry to be obliged, for the first time in my life, willingly to disobey you,” she wrote to her mother.

She began her journey on May 14, 1776, taking her three small daughters; one age 4, another age 2 and the youngest 10 weeks old. The baroness braved many dangers, traveling through areas infested by highwaymen, “yet I would have purchased at any price the privilege thus granted to me of seeing daily my husband,” she wrote.

Frederika accompanied her husband on campaign. “They are naturally soldiers, and excellent marksmen,” she wrote of the Americans, “and the idea of fighting for their country and their liberty increased their innate courage.” Frederika saved her husband’s regimental colors when they were taken prisoner by the Americans by hiding the colors in her mattress. She and her husband survived the war and returned to Germany, having had four additional children in North America.

Her diary remains an important firsthand source describing the events of the war. Frederika is one of many German women who made noteworthy contributions to history while supporting their husbands. It is interesting to compare her as a German officer’s wife to the wives of leaders of Nazi Germany, who had a chauvinistic vision for the role of German women. In this passage, Frederika describes the Battle of Saratoga which ended in Patriot victory on Oct. 17, 1777.

Marching with The troops

We finally reached Saratoga about dark, which was only a half hour march from the place where we had spent the whole day. I was totally soaking wet due to ceaseless rain and had to stay that way all night because I had no place to change my clothes. So I sat next to a good fire, undressed my children and then we all laid down together on straw.

I asked [Major General William] Phillips who approached me why we did not start our retreat while there was still time, because my husband had undertaken responsibility to cover the retreat and see the army through it. “Poor woman!” he answered me. “You amaze me! Although you’re soaking wet you still have the courage to wish to go on in this weather. If only you were our commanding general! He believes himself to be too exhausted and wants to stay here for the night, and give us some supper.”

In fact General [John] Burgoyne was very keen to do so; he spent half the night singing and drinking, and amused himself with the wife of a commissary, who was his mistress and loved champagne like he did.

Then I rose at 7 a.m. the next morning with some tea to wake me up, and we hoped now that things would change in an instant for us to finally continue marching away. To cover our retreat, General Burgoyne ordered for the beautiful houses and mills in Saratoga that belonged to [Major] General [Philip] Schuyler to be set on fire…

Aiding the Neglected Troops

Wretchedness of the greatest magnitude and the most extreme disorder reigned in the army. The commissaries forgot to distribute rations among the troops. There were enough cattle but none were slaughtered. More than 30 officers came to me who could not hold out much longer due to hunger. I ordered coffee and tea to be made for them…

Ultimately my provisions were depleted, and in the exasperation of not being able to help anymore, I called the General Adjutant [John] Patterson over because he happened to pass by and I told him, forcefully, the following words because these matters were weighing much on my heart: “Come here, and see these officers, who have been wounded for the common cause, and who are now deprived of everything because nobody gives them what they are owed. It is your duty to bring this to the attention of the general.”

He was deeply moved by this and the result was that General Burgoyne himself came to me within a quarter of an hour later, and thanked me very pathetically that I had reminded him of his duties…I replied to him that I asked for his pardon for interfering in things that I knew very well were not a woman’s business, but that I found it impossible to remain silent because I had seen so many brave people in want of everything and had nothing more to give them myself. He thanked me afterwards once again (although I still believe that in his heart he never forgave me for this blow)…

Dodging GunFire

At about 2 o’clock in the afternoon the sounds of cannon fire and small arms fire were heard again, and everything transformed into alarm and movement. My husband sent instructions to me that I should immediately go to a house which was not far from there.

I got into my calash [carriage] with my children, and we had hardly started going towards the house when I saw, on the opposite bank of the Hudson River, five or six men with rifles aiming right at us. Almost unconsciously I threw the children into the rear of the carriage and threw myself over them.

In the same moment the bastards fired, and completely tore up the arm of a poor English soldier behind me, who was already injured and also wanted to retreat to the house.

Just after our arrival, a frightful cannon barrage began, which was for the most part directed at the house where we were seeking shelter. The enemy probably believed that the generals were there because they saw so many people streaming toward there…We were ultimately forced to flee into the cellar, where I kept in a corner not far from the door. My children lay on the ground with their heads on my lap. We stayed that way the whole night….

Cannonballs in the House

Eleven cannonballs went right through the house and we could clearly hear them rolling right over our heads. One poor soldier, who was supposed to get his leg amputated and had been laid out on the table for this, had his other leg taken off by a cannonball in the meantime…

I was more dead than alive, but not so much over our own danger as that which my husband was facing. However he often sent men to ask how things were going for us and to let me know that he was all right…

Often my husband was of a mind to get me out of danger by sending me over to the Americans, but I protested that it would be more abominable than anything I was now enduring if I had to see and be courteous to people who at the same time were possibly killing my husband. Therefore he promised me that I would continue to follow the army…

I attempted to distract myself by busying myself a lot with our wounded… Once I undertook the care of a Major Plumpfield, adjutant to General Phillips; a rifle bullet had passed through both of his cheeks and smashed his teeth to pieces, and grazed his tongue. He could hold absolutely nothing in his mouth; any food nearly choked him and he was in no condition to take any other nourishment but a bit of beef soup, or some other liquid.

We had Rhine wine. I gave him a flask of it in the hope that the acidity of the wine would clean his mouth. He constantly took some of it in his mouth and that alone had such a salutary effect that he became healed, and thus I again made another friend. And thus I had, amid my hours of sorrow and worry, joyful moments of happiness that made me very glad.