Stuart N. Lake—part biographer, part con man—was looking to land a whale.

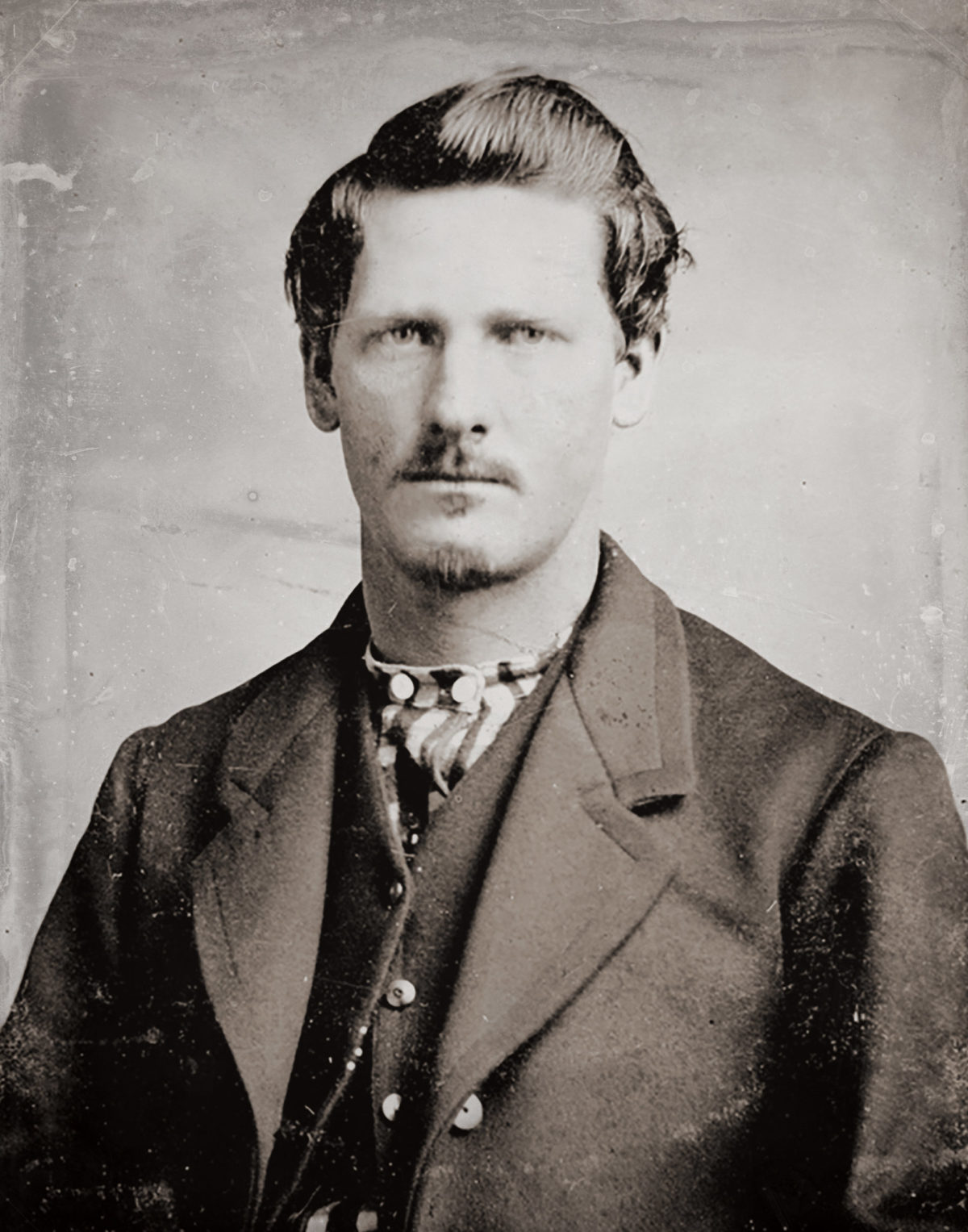

Having secured an agreement to pen Wyatt Earp’s biography, Lake managed to conduct just eight interviews with the legendary Western lawman before prostate-related health problems did for Wyatt what gunfighters in Dodge City, Tombstone and other tough towns could not. On Jan. 13, 1929, 80-year-old Earp died in Los Angeles. Undeterred, Lake resolved to complete the biography anyway. If he had to support the facts with rumors, half-truths and fabrications, so be it. Who would know?

In the meantime, Lake needed money. Hoping for a big score, on Aug. 31, 1929, he wrote to William Randolph Hearst, the newspaper tycoon and son of the late mining magnate George Hearst. In the letter Lake dangled a cane Hearst supposedly gave Earp in Tombstone. The biographer’s account of how George came to present Wyatt with the cane is quite the tale.

On arriving in Tombstone in 1881 after a perilous trip through Sonora, Mexico, and Arizona Territory to assess mining properties, Hearst learned from an undercover Wells Fargo agent that the “Curly Bill–John Ringo gang of outlaws” had concocted a scheme to kidnap and ransom him. For protection Hearst’s friends convinced him to have Earp—the one lawman the Cowboys feared—join him on his next excursion. When the two returned safely to Tombstone, Earp refused Hearst’s offer of money, so instead George gave Wyatt his cane. Lake wrote:

“Your father had a walking stick, made of buffalo bone and hand-carved by some Indian, which he had carried for several years, ever since it had been given to him by the chief of a tribe—Sioux, I think—during a visit to the Deadwood country, in the course of which your father promised to exert his influence in behalf of certain matters of moment to the tribesmen. He had this stick in his hand at the time of parting from Wyatt Earp in Tombstone and, as Wyatt himself told me on several occasions, insisted that he accept it as a memento of their trip through the Arizona wilderness.…

“Wyatt was reluctant to accept the gift, but your father climbed into the Benson stage and left the marshal standing in Allen Street with the stick in his hand. For the next 47 years, until his death, Wyatt Earp kept the buffalo-bone cane with him wherever he went.…After his death Mrs. [Josephine] Earp gave the stick to me.”

Passed from a Sioux chief to George Hearst to Wyatt Earp, the buffalo-bone cane certainly had a rich history. But was it all hogwash? Could it be Lake was trying to flimflam W.R. Hearst into buying a worthless stick of no historic value? By examining the actions and whereabouts of Earp and George Hearst when both were in Arizona Territory, we can determine whether Lake’s story behind the buffalo-bone cane holds up or is the stuff dreams are made of.

Hearst Heads to Arizona Territory

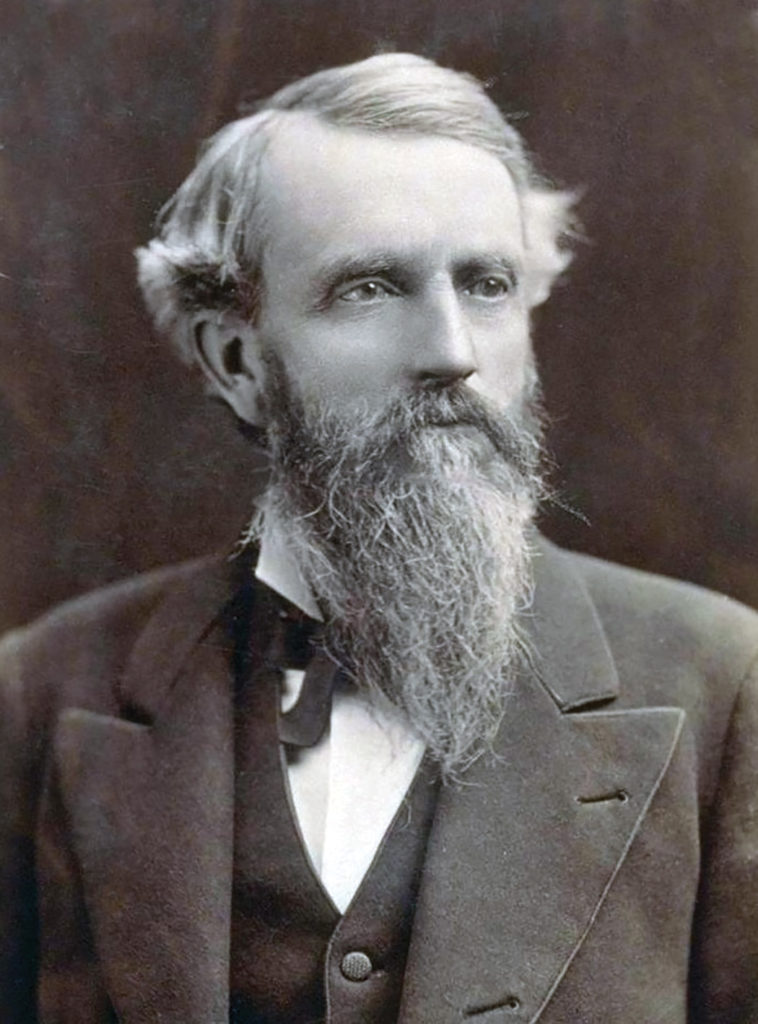

In September 1878, feeling his oats after having acquired the richest gold mines in the Black Hills, Hearst turned his attention to the silver diggings in Arizona Territory. A year earlier Army scout turned prospector Ed Schieffelin had wandered into Apache country east of the San Pedro River in search of gold. Fellow scout Al Sieber had reportedly warned Schieffelin he’d find nothing but his tombstone. But the gamble paid off. Schieffelin struck a rich vein of silver and named his claim Tombstone after Sieber’s jest. A flood of prospectors had followed, giving rise to the namesake settlement and drawing Hearst’s attention.

Born into a slave-owning family in Missouri Territory on Sept. 3, 1820, George Hearst traded the reliable income of the family-owned farms and general store for the capricious promise of the California Gold Rush. Reaching the diggings in the fall of 1850, Hearst scrabbled about for several years at various enterprises. He made his first real killing during the frigid winter of 1859–60 by driving a pack of mules laden with tons of silver the 250 miles southwest from Virginia City, Utah Territory (in present-day Nevada) to San Francisco for smelting. By the time the first shots of the Civil War rang out at Fort Sumter, S.C., Hearst was a millionaire. Given his almost oracular mining successes, Hearst helped accelerate the rush to Tombstone merely by showing interest.

Wyatt Earp was among the silver seekers who took notice.

Born in Monmouth, Ill., on March 19, 1848, Earp had followed a meandering path to law enforcement stints in Lamar, Mo., and Wichita and Dodge City, Kan. Having largely tamed the latter cow town by the fall of 1879, Wyatt swallowed the lure of El Dorado and headed for Tombstone. Earp and traveling companions—Wyatt’s common-law wife Mattie Blaylock, his brother James and Jim’s wife, Bessie, and her children—may have raised eyebrows when they stopped en route in Las Vegas, New Mexico Territory, to seek out John Henry “Doc” Holliday and Doc’s common-law wife, “Big-Nose” Kate Horony. After all, Doc had killed cantankerous Army scout Mike Gordon in a local saloon that July, and the safest way to not provoke the tubercular gambler was to stay the hell away from him. But Wyatt counted Doc as one of his truest friends, and together they traveled to Arizona Territory. In Prescott they added Wyatt’s brother Virgil and his common-law wife, Allie, to their party, which reached Tombstone in the closing weeks of 1879.

Wyatt’s projected moneymaking enterprise was a bust. “I intended to start a stage line when I first started out from Dodge City,” he recalled. But two lines were already operating in Tombstone, so he sold his outfit. By July 1880 he was working as a shotgun messenger for Wells Fargo. He was still guarding the stages that ran between Tombstone and Benson when Hearst appeared in Arizona Territory.

On Feb. 4, 1880, Hearst checked into Tucson’s Cosmopolitan Hotel. In May he ventured to Sonora, Mexico. There Hearst met with the Elias family and purchased from them the Boquillas land grant, some 10 miles northwest of Tombstone, which included the Contention silver mine. On June 12 Hearst was in Harshaw, Arizona Territory, within 10 miles of the southern border, where he acquired and began improving an old Mexican property colloquially known as “the Trench.” Although a dearth of lumber forced a temporary halt to construction, the Trench soon boasted a 40-foot tunnel and a shaft plunging 106 feet. From there Hearst traveled on 50 miles northeast to the Boquillas grant. Some of the land he sold, while on the most promising sections he began work on a railroad, started a cattle ranch and built up the Contention mine.

On July 18 Hearst sent an update from Tucson to business partner James Ben Ali Haggin. “I have done more and accomplished less, so far than I would like,” he wrote. “I assure you this is the hardest place to accomplish anything I have ever met.” Hearst was soon back in San Francisco.

Although it is conceivable that between Feb. 4 and July 18, 1880, Hearst may have ridden in a Wells Fargo stagecoach with Earp as his protector—potentially forging a lasting friendship—no such connection can be found in contemporary letters, diaries, or newspaper accounts. Newspapermen would have been especially keen to spot Wyatt speaking with the mining magnate during Hearst’s visit to Arizona Territory late the following year, for in the interim Earp would eclipse Hearst as the most talked-about man in the territory.

Fear in Tombstone

Stepping off a train at the Tombstone depot late on Christmas Day 1881, Hearst found a different town than the one he’d left. Fear rather than festivity pervaded the air.

The tensions revolved around an ongoing bloody feud between the Earps and a band of rustlers and killers known as the Cowboys. Under the nebulous leadership of gunmen Curly Bill Brocius and Johnny Ringo, the Cowboys particularly chafed at a new ordinance that prohibited the carrying of firearms within town limits. Enforcing the ban were Wyatt and brothers—once again lawmen. Virgil was the city marshal (police chief), Wyatt and younger brother Morgan his assistant marshals. Although Doc didn’t wear a star, on October 26 he’d backed the Earps in a gunfight behind the O.K. Corral that had claimed the lives of three Cowboys—Billy Clanton and brothers Tom and Frank McLaury. Virgil and Morgan had been shot, Doc grazed. Wyatt, miraculously, was unhurt.

Hearst, a pragmatist who had taken a neutral stance during the Civil War, wanted nothing to do with the dispute. Three days after his return to Tombstone, the feud hit another flash point. At 11:30 p.m. on December 28 Virgil was ambushed outside the Oriental Saloon. Though his left arm was shattered by buckshot, the city marshal survived.

George W. Parsons, who befriended the Earps in Tombstone and later served as one of Wyatt’s pallbearers, noted Hearst’s Jan. 3, 1882, return to town on the evening stagecoach. “Met George Hearst this morning and had quite a talk,” Parsons wrote in his journal the next day. “He seems to like the camp.”

Parsons recorded Hearst’s continued presence in camp on a “cold and frightfully windy” Friday, January 13. Despite the wind and ice, Hearst was planning to head up into the Dragoon Mountains, some 15 miles to the northeast. Given the ever-present threat of highwaymen and Apaches, Hearst needed the services of a gunhand who knew the lay of the land. If Hearst considered hiring Wyatt, he soon dismissed the notion. Instead, he tapped another Tombstone man who fit the bill—John Henry Jackson.

Born in Ontario, Canada, on April 18, 1840, Jackson had arrived in Tombstone in the spring of 1879. He and sister Francis shared an adobe house on Bruce Street and had an interest in the Omega claim. After converting a leased livery stable on Allen Street into a boardinghouse and restaurant, he’d purchased city attorney Marcus P. Hayne’s ranch in Cochise Pass and other interests in the Dragoons. To Hearst’s purposes, the 41-year-old had a commanding presence and an intimate knowledge of the mountains.

On the morning of January 14 Hearst, Jackson and a party of four others left Tombstone by stagecoach. After examining the Defiance mine, Jackson, Hearst and Hiram M. French saddled three horses from the team and rode to the more remote Dragoon, Black Jack, Hidden Treasure, Star, Lake Superior and Elgin mines. Returning to the stagecoach, they hitched their horses and, tired and hungry, drove the team back to Tombstone, dining at the popular Fourth Street restaurant Jakey’s. “Hearst was very favorably impressed with the mines,” the Tombstone Epitaph wrote. “We trust that his favorable report upon his return to San Francisco will set the great mining operators of the Pacific Coast to thinking that, after all, Arizona is worth looking after a little.”

On January 16, amid a snowy mix, Hearst purchased a stake in the Contact mine for an initial $5,000; $10,000 more soon followed, and Hearst would expend another $6,000 to develop it.

Although it didn’t snow the next day, Parsons recorded there was “much blood in the air this afternoon. Ringo and Doc Holliday came nearly having it with pistols.…Bad time expected with the Cowboy leader and D.H. I passed both, not knowing blood was up. One with hand in breast pocket, and the other probably ready. Earps just beyond.” Before either man could draw, Officer Jim Flynn pulled Ringo away, while Wyatt strong-armed Doc in the opposite direction.

In his 1931 biography Wyatt Earp: Frontier Marshal Lake claimed Wyatt rode out from Tombstone with Hearst the day after the Doc–Ringo scrape:

“The Curly Bill gang was plotting to kidnap United States Senator George Hearst, then on inspection of Cochise County mining properties, and to hold the capitalist for ransom. Senator Hearst, however, insisted on making his trip, so the [Tombstone] Safety Committee asked Wyatt to accompany him. With Wyatt, Hearst spent a week riding and camping in the mountains and desert without molestation.”

If Lake is to be believed, Hearst and Wyatt were inspecting mining properties between January 18 and 25. But, according to the Tombstone Weekly Epitaph, Hearst left town on January 22 in the company of Jackson and George A. Berry. Their destination was the Winchester Mountains, some 50 miles to the north. Wyatt left Tombstone a day later in the company of Doc, Morgan and five other men. Each was conspicuously armed with a Winchester rifle, a shotgun and two pistols. Wyatt carried a warrant for the three Cowboys—Pony Diehl and brothers Ike and Phin Clanton—he held responsible for Virgil’s shooting.

Lake’s timing was off. It’s also hard to imagine Hearst would have wanted to place himself amid the feud by standing anywhere near Wyatt. That Lake repeatedly refers to Hearst as “Senator,” though Hearst wasn’t appointed to the Senate until 1886, makes the claim even more suspect.

Jackson was back in Tombstone on January 24, organizing a separate posse to ride out and arrest Ringo. A week later Hearst left for Mexico. While the citizens of Tombstone held their breath, awaiting the next dustup between the Earps and the Cowboys, disturbing news came in from Sonora: George Hearst had been murdered.

On February 13 a Mexican rode into Tombstone telling a wild story. While making their way along a tributary of the Sonora River north of Arizpe, 100 miles south of Tombstone, Hearst and party had been massacred by Indians. News of Hearst’s death spread like wildfire and was telegraphed to his partners Haggin and Lloyd Tevis in San Francisco.

Addison E. Head, a friend of Hearst’s from their days prospecting Nevada silver, was aghast, but for a different reason. He was in telegraphic contact with the wandering magnate, who was very much alive. When Hearst returned to Tombstone on February 19, speculation abounded the Mexican had conjured the rumored massacre from the bottom of a bottle of mescal. A few days later Hearst left by train for Los Angeles. William Pinkerton, a scion of the Pinkerton National Detective Agency, was also aboard. It does not appear the detective was there to keep an eye on Hearst—but with the crafty Pinkertons, you never knew.

Cowboy Shootout

In spring of 1882 the Earp–Cowboy feud reached its bloody crescendo.

On March 18 Morgan was shot dead by a Cowboy assassin while shooting pool in the Campbell & Hatch Billiard Parlor as Wyatt stood by helplessly. Two days later Wyatt, who weeks earlier had been appointed a deputy U.S. marshal, gunned down Frank Stilwell near the Southern Pacific depot in Tucson, an act of vengeance that kicked off what historians call the “Earp Vendetta Ride.” To avenge Morgan, Wyatt had formed a posse composed of men from both sides of the law. Considering Wyatt a rogue agent, Arizona Territory Governor Frederick A. Tritle directed Cochise County Sheriff Johnny Behan to bring Earp to justice.

Recommended for you

Around 11:15 on the morning of March 22, Wyatt, Doc, Sherman McMaster, and “Turkey Creek” Johnson caught up with Florentino Cruz, who was chopping wood in a camp below the South Pass of the Dragoon Mountains. The next day Cruz’s body was found with four bullet wounds, including one to his right temple.

On March 24 Earp finally shot it out with Curly Bill. Wyatt had been hoping to get the drop on the Cowboys at Iron Springs (present-day Mescal Spring) but was outnumbered and surprised from ambush. This time the posse comprised Wyatt, Doc, McMaster, “Texas Jack” Vermillion, Jack Johnson and Wyatt’s youngest brother, Warren. Arrayed against them were Curly Bill, Milt Hicks, Johnny Barnes and a half dozen other Cowboys. Despite the odds and Curly Bill’s gun skills, Wyatt put a shotgun blast through Curly Bill’s chest. He then drew his pistol, shooting Hicks in the arm and Barnes through the chest. With Curly Bill and Barnes dead, and the Earp posse having suffered only one casualty—Texas Jack’s horse—the remaining Cowboys fled.

When Hearst returned to Tombstone the first week of April, he needed a bodyguard more than ever. Jackson was unavailable, however. Appointed a deputy U.S. marshal in the Earps’ stead, he’d been ordered by Governor Tritle to raise another posse to bring in Wyatt and party.

Hearst had other ideas.

Accepting Hearst’s offer, Jackson guided Hearst and Head some 120 miles east into New Mexico Territory’s Victorio Mountains. This was wild country, inhabited by Mexican gray wolves, mountain lions and grizzly bears. Undaunted, Hearst and Head established an expansive cattle ranch in Deming, 20 miles beyond the mountains, purchasing for $12,000 former Texas Ranger Michael Gray’s 1,000-acre property, which two years earlier Gray had paid squatter Curly Bill $300 to vacate. This acquisition, ultimately renamed the Diamond A Ranch, marked the beginning of Hearst’s New Mexican cattle barony.

On April 15 Wyatt, Doc and the others arrived in Silver City, New Mexico Territory, 45 miles northwest of Deming. The next day they sold their horses and boarded a Deming-bound stagecoach. By the time the Earp party reached that dusty New Mexico Territory town, Hearst, Head and Jackson had returned west. Hearst reached Tombstone on April 23, while Wyatt boarded a train north for Albuquerque. From there Earp drifted to Colorado, Idaho and California, then north to Alaska before settling in Los Angeles for keeps. His final resting place is beneath a tombstone at the Hills of Eternity Memorial Park in Colma, south of San Francisco, within 1,000 feet of George Hearst’s family mausoleum.

So, did Hearst give Earp the cane? It doesn’t seem likely. As Lake tells it, Hearst acquired the cane in Deadwood after having brokered a deal on behalf of a Sioux chief, but there is no evidence he had any such dealings with Indians in the Black Hills. The same goes for the supposed Cowboy plot to abduct him. Most telling, the dates don’t add up.

Walking stick aside, Hearst delivered Earp an even greater gift. By retaining the services of Jackson in the spring of 1882, he inadvertently made certain that formidable marshal spent the last days of the Earp Vendetta Ride protecting Hearst rather than chasing Wyatt.

As for the cane itself, it kicked around for decades before turning up at one of Brian Lebel’s Old West Auctions at the Will Rogers Memorial Center in Fort Worth, Texas. Both Lake’s typewritten letter and the cane were authenticated—as much as they could be—and on June 6, 2015, they were auctioned off. Starting at $20,000, the lot hammered down at $65,000. Whether or not the cane ever belonged to George Hearst or Wyatt Earp, the surrounding mythology made it worth its weight in gold.

Matthew Bernstein teaches at Matrix for Success Academy and Los Angeles City College and is the author of George Hearst: Silver King of the Gilded Age. For further reading he recommends The Dragoon Mountains, by Lynn R. Bailey; Wyatt Earp: The Life Behind the Legend, by Casey Tefertiller; and Ride the Devil’s Herd: Wyatt Earp’s Epic Battle Against the West’s Biggest Outlaw Gang, by John Boessenecker.