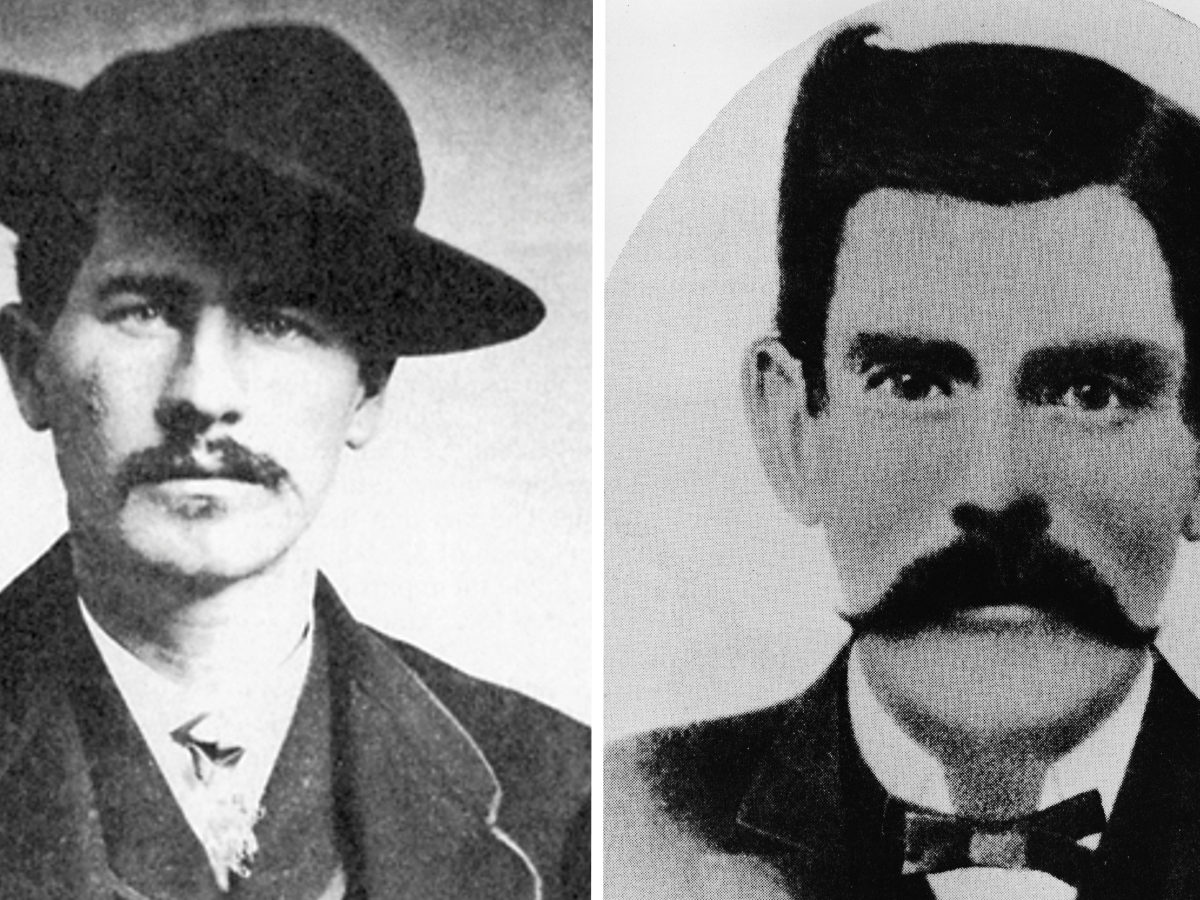

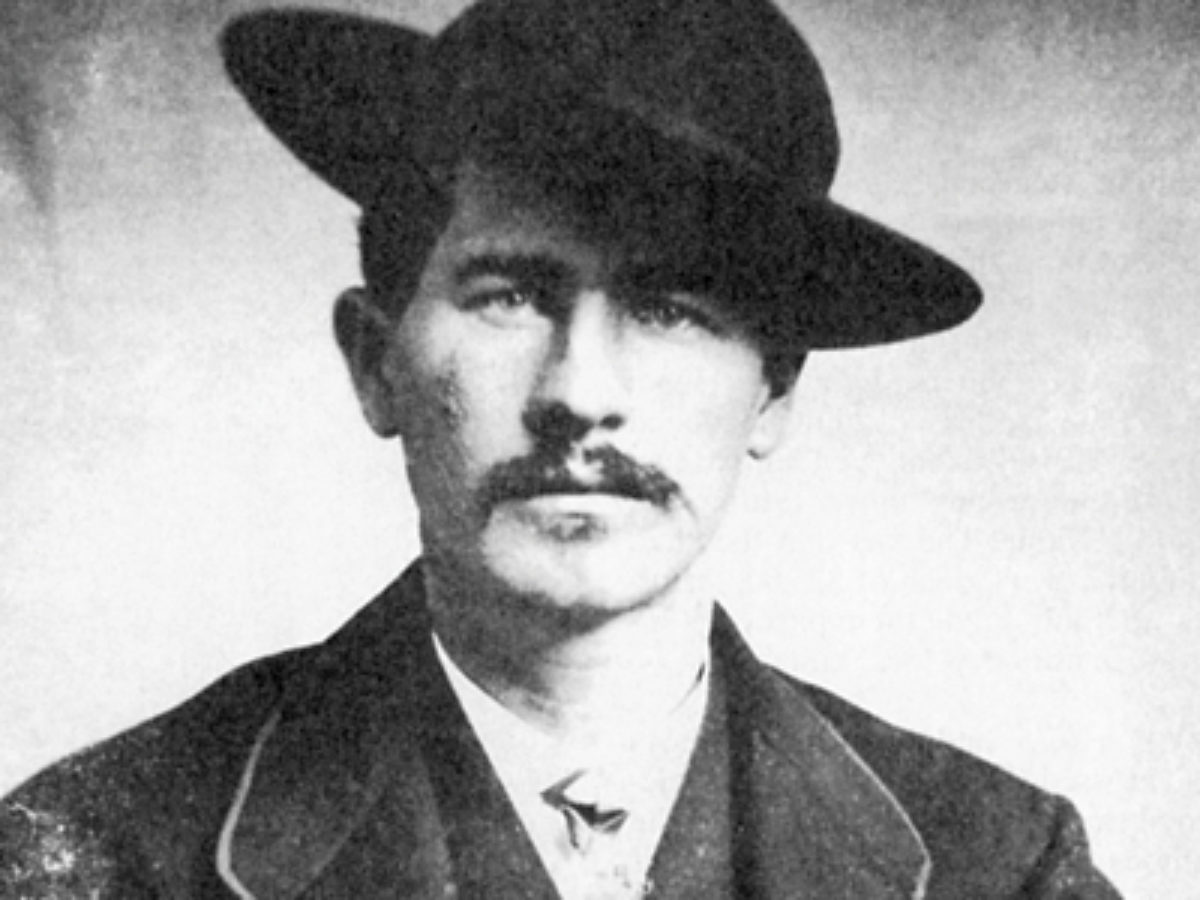

Wyatt Berry Stapp Earp stood toe to toe with Stafford Wallace Austin, court-appointed receiver of the bankrupt California Trona Co. The date was Oct. 23, 1910, and Earp, the “Lion of Tombstone,” had been reduced to working as a hired gun for a spurious survey party in southern California’s desolate Searles Valley. Though 62 and gray-haired, he retained the raw-boned, physically intimidating presence of his younger days in Arizona Territory.

“What are you doing in this camp?” Earp demanded.

Recommended for you

Earp’s concern was understandable. Accompanying Austin were four men armed, he recorded in his journal, “with all the weapons they could collect.” Confronting them were, Austin recalled, “the best-equipped gang of claim jumpers ever assembled in the West. It consisted of three complete crews of surveyors, the necessary helpers and laborers, and about 20 armed guards, or gunmen, under the command of Wyatt Berry Stapp.” The gunmen included Earp’s friend and sometime deputy Arthur Moore King, a former Los Angeles police detective. At stake were mineral claims of tremendous worth.

Valley namesake John Wemple Searles, a luckless Forty-Niner, had arrived in Southern California in the early 1860s and settled in the vicinity of present-day Trona. Though he was looking for gold and silver, what he found in the surrounding dry lake bed was borax, a valuable mineral with many uses. Searles filed claims on the property, and by 1873 his San Bernardino Borax Mining Co. was in production. He hauled his product 200 miles south to the port of San Pedro in huge wagons drawn by legendary 20-mule teams. When the Southern Pacific Railroad reached the desert town of Mojave in 1876, the wagon trip was shortened to about 80 miles. In 1895, however, weak demand prompted Searles to sell his firm to Francis “Borax King” Smith, of the Pacific Coast Borax Co., who shuttered the operation the next year.

For more than a decade various operators made repeated unsuccessful attempts to economically mine the lake for not only borax but also potash, soda ash, trona and sodium sulfate. By 1910 the claims were under the control of California Trona, which had borrowed heavily to finance construction of two experimental plants to facilitate mineral recovery. The company went bust before completing the plants. When the claims went into receivership, federally appointed receiver Austin came to secure the property from competing claimants.

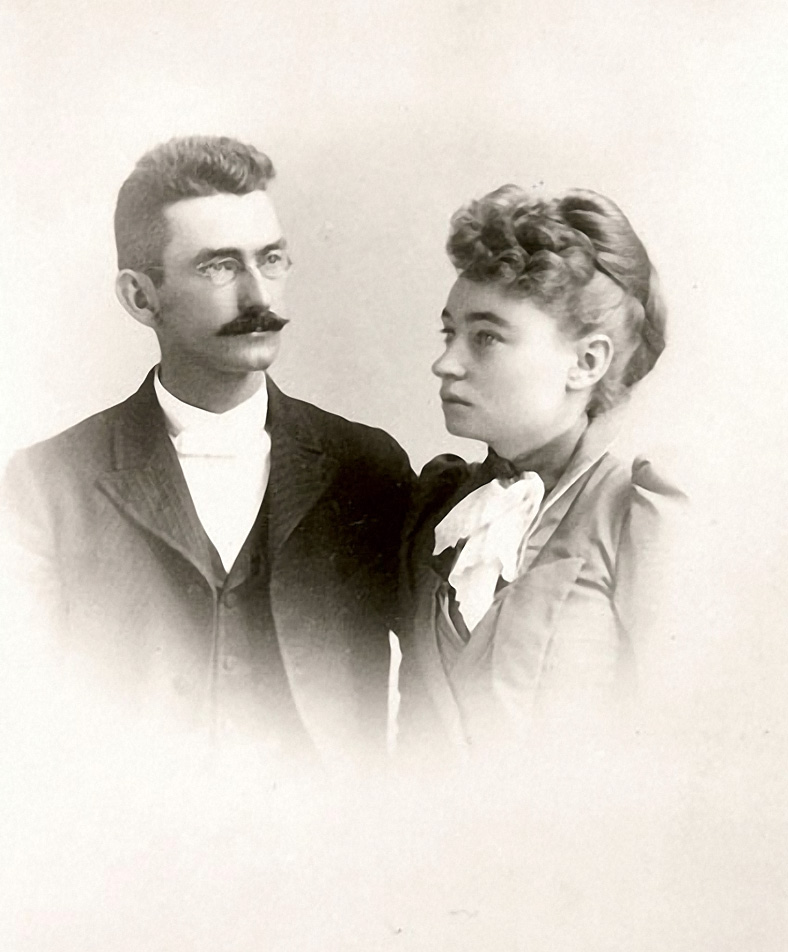

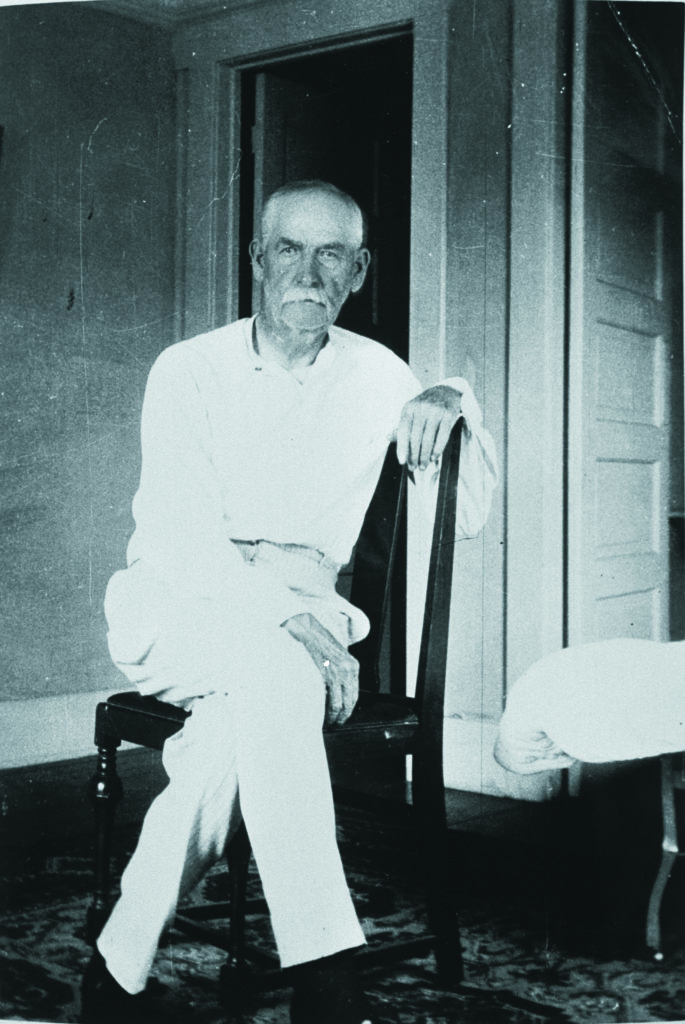

Born in 1862 and raised in Hawaii, Austin was an 1886 graduate of the University of California, Berkeley. Four years later he met and married his wife, noted author Mary Austin, in Bakersfield. In 1892 they settled in Lone Pine, Calif., at the foot of the Owens Valley. There Wallace taught school and was later elected superintendent of Inyo County schools. In 1905 valley residents banded together to confront Los Angeles officials over the city’s acquisition of water rights in the valley. Civil engineer William Mulholland had used straw buyers and other underhanded means to enable the city to pipe Sierra Nevada runoff to a reservoir in the San Fernando Valley. When Owens Valley locals woke to what was happening, they sought to stop the project. But Mulholland and company had dotted their I’s and crossed their T’s. Construction continued on the Los Angeles Aqueduct, which today provides one-third of the city’s water needs. A year later the estranged Austins left the valley and went their separate ways. Wallace was working as a lawyer in Oakland in 1909 when his firm was appointed receiver of the Searles Valley claims.

Earp’s path to Searles Valley was a long and winding one. Following the storied 1881 gunfight near the OK Corral in Tombstone, Arizona Territory, and his subsequent vendetta ride, he returned to Dodge City, Kan., for a while to help out politically embattled saloon owner and friend Luke Short. He subsequently turned up in Colorado, Idaho, California, Arizona, Nevada and Alaska, mostly engaged in the saloon and gambling hall business while seeking his fortune mining for silver and gold. Although he’d done his share of “lawing,” as he called it, Earp didn’t feel particularly called to police work. But for him and his brothers alike it had proved a reliable, albeit risky, way to make a living when their entrepreneurial ventures failed, as they usually did.

By 1910 he was dividing his time between Los Angeles and Vidal, a southern California settlement down near the Colorado River, where he held mining claims. The Los Angeles Police Department sometimes hired him and Arthur King, at $10 a day each “off the books,” to track down fugitives. While the department strictly adhered to legal means, Earp, as was his custom, did not. He and King even brought back wanted men from Mexico, extradition laws be damned, not that the department asked any questions. The partners’ reputation for success landed them a job in the fall of 1910 heading up a security team to protect survey crews hired by Los Angeles attorney Henry E. Lee. Acting on behalf of an Eastern mineral concern, Lee sought to move in on the Searles Valley claims held by the bankrupt California Trona.

As receiver of the struggling company’s assets, Austin was legally in possession of the claims and, in fact, actively engaged in improving the property and dealing with creditors, as required by law. Lee must have known that, but the potential of earning millions of dollars from the idle mineral claims loomed large. Given the 20 armed guards he’d hired to protect his survey crews, he clearly expected resistance. When Lee’s surveyors set up camp and went to work, Austin “considered it necessary to make some show of force in protecting our claims.” At sunrise on October 23 he and four armed men visited the camp.

After issuing his verbal challenge, Earp sought to wrest away a shotgun carried by one of Austin’s men. Austin in turn drew a pistol and ordered Earp to release the shotgun, which he did. But things were just heating up. “I’ll fix you!” Earp barked.

From that point in the standoff accounts vary. According to King, Earp ducked into a nearby tent, emerged with a Winchester rifle and again squared off with Austin. “Back off or I’ll blow you apart,” he said, “or my name is not Wyatt Earp!” He then fired the Winchester into the ground beside Austin—“the nerviest thing I had ever seen,” King noted—forcing the latter to back down and leave. Austin had a different recollection. “Just as things seemed to have quieted down,” he recalled, “one of the excited jumpers accidentally discharged a gun. No one was hurt, but it was a very tense moment for all of us. Having failed to dislodge the enemy, the next day I called for a U.S. marshal, and when he arrived, the claim jumpers were all arrested and sent home, including Wyatt Berry Stapp, none other than the famous marshal Wyatt Stapp Earp.” Two years later Lee put together another survey crew, but a federal court intervened to protect California Trona’s claims.

Austin’s actions kept the firm afloat, and the mineral works have remained in operation to this day. In 1914 he was appointed Trona’s first postmaster, and four years later American Trona, the successor to California Trona, hired him as its Los Angeles office manager. As for Earp, the Searles Valley “potash war” represented his last known armed confrontation. He’d spend his waning years hobnobbing with Hollywood types and trying to get a film made of his storied life.