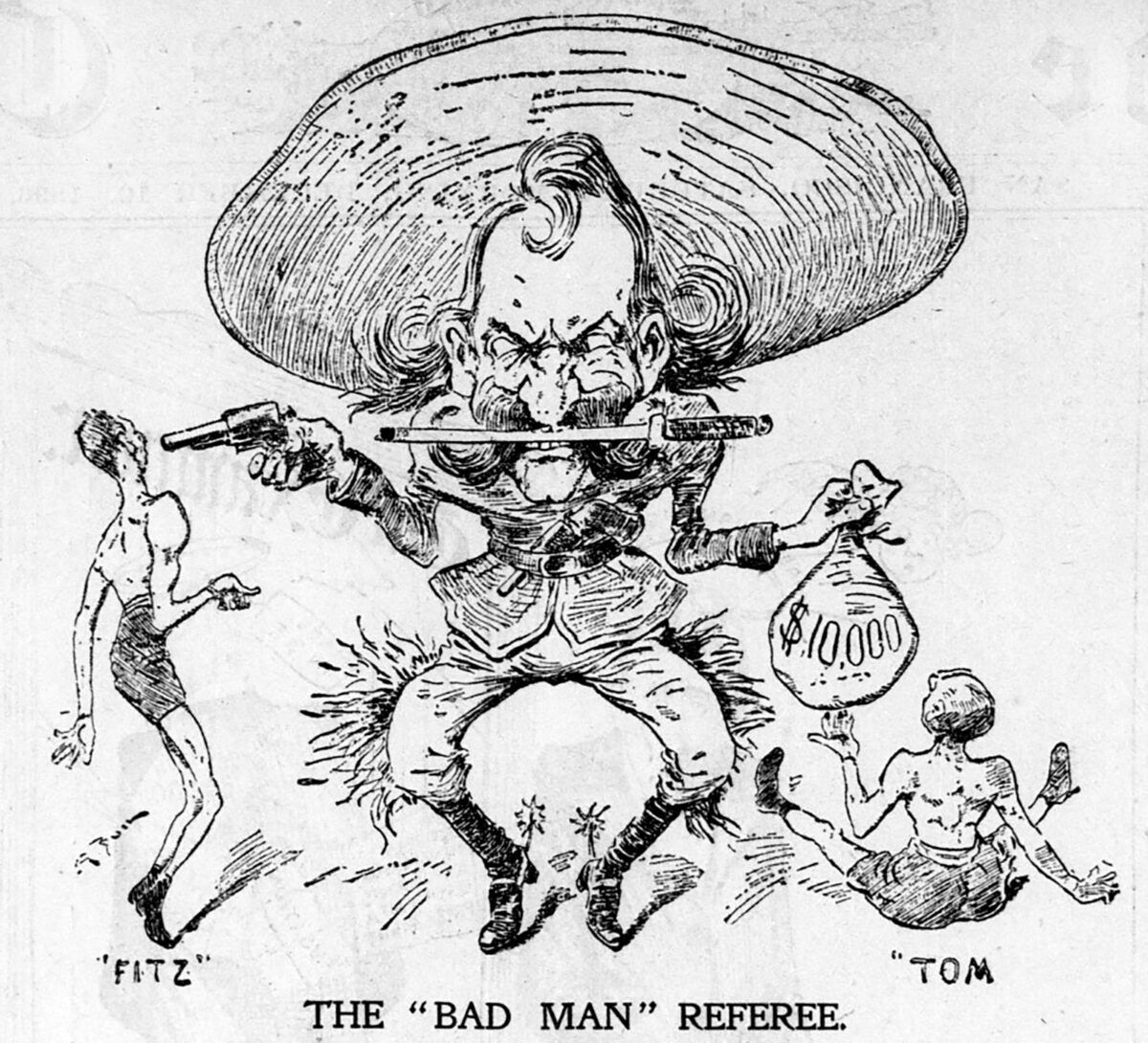

Wyatt Earp’s bitterest enemy, one he could never vanquish, was not a Clanton, a McLaury or one of the other Cowboys. It was a 2-inch-tall cartoon character in an oversized sombrero. The mustachioed figure, a knife clamped in his teeth, would haunt Earp the last 32 years of his life.

The image appeared originally in The New York Herald and was reprinted in The San Francisco Call on December 12, 1896. Ten days before, Earp had stood in a boxing ring at San Francisco’s Mechanics Pavilion, the referee in a bout between Bob Fitzsimmons and Tom Sharkey, two of the country’s best heavyweights. In the eighth round, Fitzsimmons, to that point the clear winner, sent his opponent sprawling to the canvas with what Earp judged a low blow. As he’d done all his life, the old frontier lawman acted decisively, in this case calling the fight for Sharkey.

The decision ignited an explosive controversy in four San Francisco newspapers that soon mushroomed across the land. It persists today, centering on the question, Was Earp a crook? More specifically, Did he take a bribe to fix the fight for Sharkey?

The uproar over Earp’s decision grew so large that it did more to define him in the public’s mind, at least in his time, than his work as a lawman in Dodge City, Kan., or even the gunfight near the O.K. Corral in Tombstone, Arizona Territory. “No previous event in his life was as important as the boxing match in making his name a household word,” said Jack DeMattos, author of The Earp Decision, which chronicles the bout and the controversy. The decision certainly attracted more publicity than the 1881 Tombstone shootout. But the bout and the gunfight were similar in one important respect—each brought Earp great personal torment.

The doubts raised about Wyatt Earp’s character in the fight’s aftermath constituted an enemy he couldn’t knock down. Earp was powerless to salvage his honor against those who sniffed a fix and screamed it to eager reporters. And the Herald’s cartoon image—a cackling, washed-up ruffian pointing a gun at Fitzsimmons with his right hand while slipping a bag of cash to Sharkey with the left—depicted their disdain in piercing black and white. His armed foes at the O.K. Corral could hardly have hurt this proud man more.

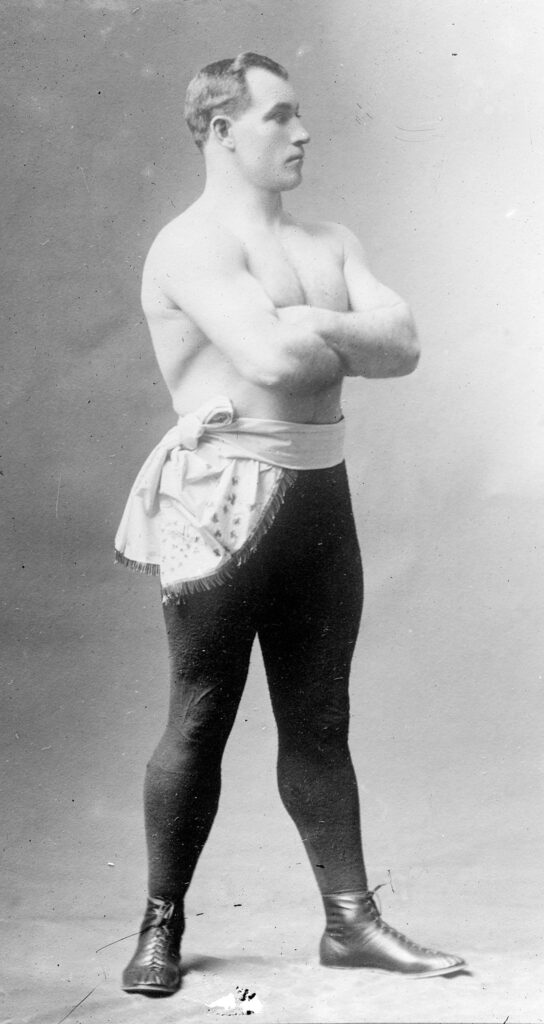

Earp, then 48, had limited experience in the fight game prior to December 2, 1896. He’d boxed as a teenager and later refereed matches at frontier railroad and buffalo-hunting camps. He’d also refereed a couple of bouts in southern California and about 20 more across the line in Tijuana, Mexico. But Sharkey vs. Fitzsimmons was no border brawl. The match drew 10,000 fans, some from society’s elite, and they forked over an outrageous $10 per seat to see what was billed a championship match.

The fight buildup dominated San Francisco’s papers for a month. Reporters combed the backgrounds of both pugilists for some new angle to stand out from the competition. The Examiner found a beaut when it reported that before arriving in San Francisco, 33- year-old Fitzsimmons had suffered the loss of his pet lion, Nero, leaving him distraught. The English-born fighter, who spent his boyhood in New Zealand painting carriages in a foundry, had chained the lion to a Cleveland rooftop, where the exotic pet contacted a live wire and was, as the paper put it, “completely electrocuted.”

Coverage of this episode said much about the pre-fight atmosphere. Everybody was jazzed, and Earp played an unwitting role in fanning the hype. In August of that year, he had collaborated with a writer for William Randolph Hearst’s Examiner on three articles about his Wild West experiences. They appeared under Wyatt’s byline on successive Sundays and packed all the blood and thunder readers could want. The stories resurrected Wyatt as a frontier hero. But when the boxing controversy broke, the serial only made him a juicier target—the incorruptible frontiersman exposed. Then as today, the bigger the celebrity, the more reporters delighted in taking him down.

And there’s more. Years before in Tombstone, Earp had worked as bodyguard to Hearst’s father, George, then a mining magnate who traveled to the silver boomtown looking for investment opportunities. The newspaper series was a kind of thank-you to Earp from the younger Hearst for the consideration Wyatt had shown his father.

But for The Examiner’s bitter rival, the upstart San Francisco Call, this connection between Earp and the Hearsts was enough to make Wyatt its enemy as well. The Call used its pages to repeatedly savage him. In this, author DeMattos says, the paper was ahead of its time, the first to partake of the “rabid Earp debunking that has remained an element of Wild West literature right up to the present day.”

Initially, Wyatt declined when the sponsoring National Athletic Club asked him to referee. But he quickly changed his mind. “I think the two best men in the world are coming together now,” he said. “I don’t know but what it will be a little bit of tone for me to referee a fight of this kind.”

Controversy erupted even before the opening bell when Fitzsimmons’ manager, Martin Julian, entered the ring and called for Earp’s removal as referee, citing whispers of a fix. Earp offered to settle the argument by withdrawing, but Sharkey’s corner insisted Earp was their man and wouldn’t relent.

With this debate ongoing, police Captain George Wittman noticed a suspicious bulge in Earp’s coat pocket. It was a gun. Wittman asked him to hand it over, and Earp complied. As The Examiner’s Edward Hamilton noted, “For the first time in the history of the prize ring in California, it was necessary to disarm the referee.” The Call reported that Wyatt “showed the ‘yellow dog’ in him by going into the ring with a Colt’s Navy revolver in his pocket.”

As expected, the veteran Fitzsimmons, known as Ruby Bob, was winning the championship bout handily through seven rounds. The shorter and younger Sharkey, then 23 and nicknamed “the Sailor” (the native of Ireland was once a cabin boy on an oceangoing vessel and in 1892 joined the U.S. Navy), was no match for the heavy-punching Fitz. In the eighth round, Ruby Bob nailed Sharkey with a left to the chin. He followed with a crushing body blow, his famed solar plexus punch, an uppercut that stole his opponent’s wind. Sharkey collapsed to the canvas with his hands over his groin.

One of Sharkey’s trainers rushed into the ring crying foul. Fitzsimmons only grinned as he walked to his corner, pointing “toward Sharkey, as if insinuating the Sailor was trying to make it appear that he had not been struck fair,” according to The Examiner. With police in the ring to keep the crowd back, Earp coolly walked to Sharkey’s corner and proclaimed him the winner.

The decision and the punch that precipitated it stunned the audience, says Inventing Wyatt Earp author Allen Barra, because prior to Fitzsimmons, few fighters had made such an art of knocking a man down with a body blow. It was new to the crowd.

Also new were the guidelines governing the match—the Marquis of Queensbury rules. They introduced a different way of boxing, including a provision for low blows, intended to move the fight game away from anything-goes brawls. But the Queensbury rules had only been in effect a short time. They were new to Earp and most of the crowd. Barra says no one expected this long-awaited fight to end suddenly on a foul many never saw.

Examiner writer W.W. Naughton, for one, believed Sharkey was indeed hurt. “If he were not in agony,” Naughton wrote, “all I can say is that he must be a consummate actor and must have rehearsed that particular scene many a time and often.” But Fitzsimmons and his corner men screamed fix, and their voices grew louder after Sharkey was carried away “limp as a dishrag” but then refused to allow the athletic club’s physician to examine him.

Sharkey did allow Dr. D.D. Lustig to see him at a hotel 18 hours later, and the doctor described the encounter in a letter to The Examiner. It only made the fight’s outcome seem even more suspicious. Lustig did indeed see swelling and discoloration on Sharkey but wrote that if it were caused by a blow from Fitzsimmons, it “would be far greater than it is at present.” He also wondered why Sharkey, if he were suffering such severe pain, wouldn’t allow physicians to examine him right after the fight.

Sharkey’s unusual behavior bolstered Fitzsimmons’ charge that he was robbed of the $10,000 purse. “What is more,” Fitzsimmons told reporters, “I knew I was going to be robbed before I entered the ring.” He alleged that several men had approached his manager on fight day with a warning not to accept Earp as referee, “because he agreed to throw the fight to Sharkey, for a good sum of money.”

The Call trumpeted this angle under insulting headlines: THE CORNISHMAN WAS WARNED AGAINST ACCEPTING THE EX-FARODEALING SHARP! For his part, Earp said his only regret was not handing the fight to Sharkey earlier, given Fitzsimmons’ dirty tactics. He was unambiguous in calling the allegations against him rubbish. “I felt that I did what was right and honorable, and feeling so, I care nothing for the opinion of anybody,” he told The Examiner. “I saw the foul blow struck as plainly as I see you, and that is all there is to it.” If he were going to favor anybody, he added, it would be Fitzsimmons, because Bat Masterson, “the best friend I have on earth…had every dollar he could raise on Fitzsimmons.” But Earp’s actions following the bout would tarnish his claim to purity.

The morning after the fight, Earp went to the Ingleside racetrack, where he man- aged horses, apparently unaware the police were looking for him. When they caught up to him at a restaurant that night, Earp went willingly to the station. Captain Wittman arrested him there on the charge of carrying a concealed weapon. “I did not expect to be arrested, or I would have surrendered myself,” he said.

“I would have arrested you at the fight,” said Wittman, “but fearing trouble, I concluded to wait until today.”

“You did not think I would run away?” Earp asked.

“I knew where to get you,” answered Wittman. “You could not have avoided us very long.”

Earp paid a $50 fine, but many still wanted to know why he carried a gun into a boxing ring? Earp said he simply forgot it was in his pocket. He always carried a gun because of late nights at the track. He also needed it because of his work as a lawman. “My life is constantly in danger from people I have sent to state’s prison from Arizona, New Mexico and Colorado, who have threatened to kill me when their terms expire, and some are expiring now,” he said. “If these men knew I had no weapon with me, there would be a general onslaught upon me.” But skeptics wondered how he could forget that a Colt .45 with an 8-inch barrel was in his coat.

When Fitzsimmons brought his claim of a fix before a judge, hoping to deny Sharkey the $10,000 purse, Earp again came off badly. Although subpoenaed to testify, he earned another arrest warrant by failing to show up. Finally appearing, he spoke to the judge in a barely audible voice, apologizing and saying he put the subpoena in his pocket and “clean forgot about it.” Even though the judge accepted his apology, it looked as if the famous lawman had been dodging the law.

But by this time, the party was on, as newspapers printed cartoon after cartoon and reporters hunted through Wyatt’s frontier past for episodes to retell, especially those in which he came off looking bad. The Chronicle delighted in noting the difficulty many in court had pronouncing Earp’s name: “The bailiffs call, ‘Wah Yah,’ Colonel Kowalsky addresses the referee as ‘Wat Yirrup,’ while witness Smith mentions him as ‘White Hurp.’ General Barnes with no regard whatsoever for the gentleman’s feelings invariably refers to him as ‘Wart Up.’” Even the judge punted on the pronunciation, at one point saying, “Now, witness, where did you first see —er, this—er, this man who officiated at the fight?”

Noted novelist Alfred Henry Lewis joined in, calling Earp “crooked as a dog’s hind leg.” Lewis was merciless, writing: “If there are any honest hairs in his head, they have not grown since he left Arizona. He is exactly the sort of man to referee a prize fight if a steal is meditated and a job is put up to make the wrong man win.” But amid the ridicule, and for all these decades afterward, no one has produced evidence of Earp’s complicity. Most view it in the context of the Tombstone saga: Those who believe Earp behaved badly in Arizona Territory tend to think he was involved in a San Francisco fix.

“It seems so shady,” says Steve Gatto, author of eight books of Western history. “A man is winning a fight, then a foul is called, and the fight is handed to the clear loser. My gut feeling is Wyatt had something to do with a fixed fight.”

About the gun in Earp’s pocket, Gatto offered an interesting insight. “It’s ironic that Wyatt was heeled that night in San Francisco but not the night Fred White was killed in Tombstone. That night he had to borrow a gun. Maybe he carried a gun into the ring because he was involved in some shenanigans.”

Barra had always assumed the fight was fixed, until he talked it over with boxing expert Bert Sugar, former editor and publisher of the magazine The Ring. Sugar explained that if someone wants to fix a match, the fighter simply takes a dive. The effort rarely involves the referee. More important, Sugar told Barra, if there were a fix, why would Sharkey wait until the eighth round to go down? After all, he was going against a stronger puncher who could’ve put Sharkey on the canvas, unconscious, at any time.

Based on his talks with Sugar, Barra, who covers sports for The Wall Street Journal, now suspects Sharkey’s corner might’ve used Earp in a plot to win the fight without Earp’s foreknowledge. “I think Sharkey had a choice,” says Barra. “He could stand there and keep getting punched out by Fitzsimmons, or take a dive and walk away with the $10,000. What would you do? Sharkey’s corner, wanting someone as inexperienced as Earp to referee, tells me they had something planned.”

Lee Silva, author of Wyatt Earp: A Biography of the Legend, doesn’t believe the Earp-fix allegation either, and not because Wyatt had such high morals. He says Earp was a “totally addicted gambler” and would have zero interest in a predetermined outcome. “He wouldn’t be attracted to a sure thing,” says Silva. “It would’ve taken the gamble out of gambling, and that wasn’t his style.” And the gun shouldn’t shock anyone. “Everybody I interviewed who knew Wyatt said he never went anywhere without a pistol,” says Silva.

The San Francisco judge who heard the case against Earp gave him a victory of sorts, letting Wyatt’s ruling stand on the basis that prizefighting was illegal. But that murky ending only guaranteed the controversy would persist.

It flared to life 13 years later in New York City when Bob Edgren, sports editor for The Evening World, wrote a column again asserting Earp’s guilt in the matter. Edgren threw in a few swipes at Bat Masterson, then a writer for a rival paper, and some nonsense about Wyatt notching his pistols to count up his murder victims. Telling of the episode, Masterson’s best biographer, Robert DeArment, wrote that Earp responded with a letter blasting the columnist, saying he’d “like to cut 12 neatly carved notches on Bob Edgren’s lying tongue.”

A few years after that, writer Eugene Cunningham interviewed Sharkey and asked about the fight. Cunningham said Sharkey looked at the ceiling, seemingly embarrassed. He muttered that there was “more to it than folks knew about,” and he saw “no use talking about it.” Troubling as it sounds, for the pro-Earp side, the encounter has to be judged in light of Cunningham’s notoriously anti-Earp views.

On it goes. In the early 1980s, San Francisco’s Court of Historical Review, a group that meets to reconsider historical disputes, held a mock trial on the Earp matter. Into a modern courtroom came history fans, retired boxers and even descendants of the Earp family, all eager to hear expert witnesses on both sides. As is usual for anything Earp related, the seats were filled, and when the verdict was read, according to one account, the standing-room-only crowd broke into applause at the news Wyatt had been cleared.

Such interest seems appropriate for a matter that clouded the remainder of Wyatt’s life. In 1897 he followed a lifelong pattern and joined the gold rush to Alaska, far from the journalistic Chihuahuas nipping at his heels. He wanted to flee to a remote place and forget. But the fight followed him, a haunting shadow that darkened his name and made it difficult to find work. Except for meaningless jackpot bouts, he didn’t work as a referee again. And except for brief success in the saloon business in far-off Alaska, he lived his last years in poverty, this, too, partly a residue of San Francisco, 1896.

Another aftershock was Wyatt’s decision to refuse virtually all press interviews in the decades following the match. He called notoriety the bane of his life. “I detest it,” he wrote bitterly in a 1925 letter. Wyatt’s long winter out of public view raises several questions: How would his life have changed if he’d said no when the National Athletic Club asked him to referee the fight? Would history’s view of Earp be different if he’d talked to newspapermen over those 30 years, rather than shunning them? What more might we know about the O.K. Corral, his vendetta afterward and his relationships with his life companion Josie and his gambling pal Doc Holliday?

We can’t say. But we do know the San Francisco fiasco, so perfectly captured by that demeaning cartoon, left a stain on his honor that proved tougher to fight than any outlaw.

Leo W. Banks writes from Arizona. Recommended: The Earp Decision, by Jack DeMattos; Inventing Wyatt Earp, by Allen Barra; and Wyatt Earp: The Life Behind the Legend, by Casey Tefertiller.

Originally published in the August 2010 issue of Wild West.