Navy Lieutenant junior grade Edward H. “Butch” O’Hare first experienced the often deadly phenomenon known as “friendly fire” right after he shot down five Japanese bombers in less than five minutes February 20, 1942, to become the Navy’s first fighter ace of World War II. Coming in for a landing on the carrier Lexington, which he had just saved from possible destruction, O’Hare came under fire from a nervous machine-gunner on the ship’s catwalk. He survived unscathed because the young sailor’s aim was no better than his judgement.

But his luck would run out 21 months later during the bloody Tarawa campaign in the Central Pacific. O’Hare disappeared without a trace during an experimental night-fighter operation on November 27, 1943 (November 26 in the United States). Many naval historians—including Clark Reynolds, author of The Fast Carriers and Edward P. Stafford, author of The Big E—believe he was the victim of friendly fire from another Navy aircraft.

The mystery of O’Hare’s death is similar in many ways to that surrounding the murder of his father in November 1939. The senior O’Hare died in a hail of gunfire on a Chicago street. Some believe his death was retribution for informing on Al Capone and helping the federal government send him to prison for tax fraud. But the case was never solved, nor were the killers ever indentified.

The Navy’s official announcement of O’Hare’s February 20, 1942, triumph over the five bombers was made on March 3, and he was erroneously credited with six victories. Numbers aside, it was just about the best war news the demoralized American public had heard since the disaster at Pearl Harbor three months earlier. In a scant five minutes of action, the St. Louis native had destroyed the growing myth of Japanese invincibility and restored the nation’s confidence in its fighting men.

No slouch when it came to shaping public opinion, President Franklin D. Roosevelt made the most of this opportunity to boost moral. When Lexington returned to Hawaii, he had the nation’s newest hero flown to Washington so he personally could present him with the Medal of Honor at White House ceremonies. Flashing the famous FDR grin, the commander in chief also informed O’Hare that he had been jumped two ranks to lieutenant commander. The citation for the medal credited O’Hare with saving Lexington from serious damage by single-handedly taking on none twin-engined Japanese bombers, shooting down five of them and severely damaging a sixth through “extremely skillful marksmanship.” Sparing no superlatives, it called the aerial battle “one of the most daring, if not the most daring single action in the history of combat aviation.”

O’Hare’s own description of the battle was somewhat more prosaic. He told reporters: “We had 10 planes in the air. The first crowd of our fellows was working the first bunch of Japs to come over, and we had the second bunch all to ourselves. I was leading a second section of two planes and my wingman had gun trouble for about five minutes, and by the time he got his guns fixed it was all over.”

Recommended for you

After the Washington ceremony, O’Hare made a series of public appearances around the country to boost home-front spirits and inspire war-plant workers to even greater efforts. His first stop was the Grumman plant in Bethpage, New York, N.Y., which made the F4F-3 Wildcat he had used to score his five victories. The it was on to St. Louis, where he was given a triumphant parade through the city and hailed by the mayor as “Eddie O’Hare, the St. Louis boy who has come home to the rolling thunder of worldwide applause.”

The handsome 28-year-old Naval Academy graduate wore the victor’s laurels well, if somewhat uneasily. Syndicated columnist Inez Robb noted that O’Hare was the “model hero—modest, inarticulate, humorous, terribly nice and more than a little embarrassed by the whole thing.”

Out of respect, perhaps, no one mentioned O’Hare’s father, who had been the president of Chicago’s Sportsman’s Park racetrack and a close associate of Al Capone. The elder O’Hare’s exact role in the Capone syndicate long has been a matter of dispute. Some called him a fringe player who restricted himself to legitimate racing activities; others depicted whims a “one-man brain trust in the mob.”

It is not clear how much Butch O’Hare knew about his father’s shady business connections. Probably it was not a great deal, since his parents had separated when he was still a boy, and later divorced. Moreover, when his father moved to Chicago, the young O’Hare remained with his mother and two sisters in St. Louis until he left home to attend military prep school in Alton, Ill. But he remained the apple of his father’s eye, and the two were extremely close. In fact, young Eddie may have been the reason the senior O’Hare decided to turn on Capone and help the government build its case against the Chicago crime czar.

According to one popular version of this classic double-cross, the senior O’Hare wanted to “square” himself with the government in order to improve his son’s chances of acceptance at the Naval Academy. It makes a nice story. And, if true, it means that the Bureau of Internal Revenue got Capone while the Navy got Butch O’Hare as part of a package deal.

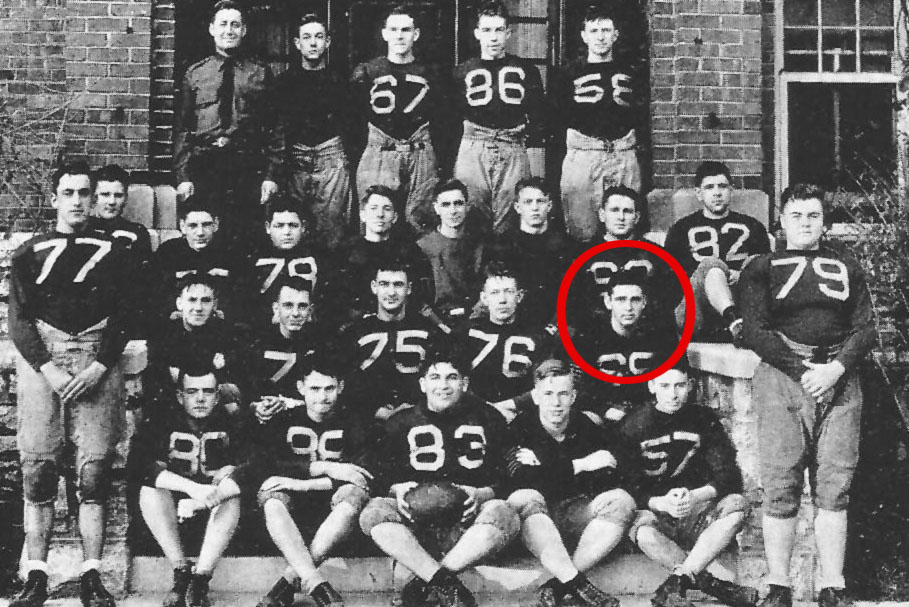

Fortunately, none of the father’s sins rubbed off on his son. Young Eddie O’Hare grew up to be the proverbial straight arrow. He prepped at Western Military Academy, where he consistently earned good grades. He played guard on the football team and was captain of the rifle team. One of O’Hare’s friends was another young man who also would make a name for himself in World War II—Paul Tibbets, who piloted Enola Gay, the Boeing B-29 Superfortress that dropped the first atomic bomb on Japan.

In 1933, O’Hare realized a long-cherished dream of winning an appointment to the U.S. Naval Academy in Annapolis, Md. Some writers have suggested that Frank Wilson, who directed the federal investigation of Capone, pulled strings to have him accepted. But Wilson, who became chief of the Secret Service in 1936, never made any such claim in his writings. Indeed, O’Hare failed on his first try for the Academy and had to return to school in St. Louis in order to improve his math skills.

O’Hare graduated from the academy with the Class of 1937 after a more or less routine four years, during which he picked up two nicknames—”Butch” which stuck, and “Nero,” which did not. His yearbook noted that he had the traits of a good officer and future leader: “a winning personality … no trouble in making lasting friendships … always ready with a pat on the back when you need it most.”

O’Hare set his sights on a career in naval aviation following graduation, but he first was required to serve two years in the fleet. In June 1939, after a tour on the USS New Mexico, he was reassigned to the Pensacola Naval Air Station in Florida for flight training; he earned his gold Navy wings a year later. He then was sent to Fighting Squadron Three (VF-3) under the legendary John S. “Jimmy” Thach, who developed the team fighting tactic (the “Thach Weave”) that allowed the slow but sturdy F4F Wildcats to hold their own against the more nimble Mitsubishi A6M Zeros.

Admiral Thach later recalled in an interview that O’Hare had all the attributes of a true fighter pilot. In addition to being a fine athlete, he had “a sense of timing and relative motion that he may have been born with.” Even more important perhaps, he possessed “that competitive spirit” that quickly separates winners from losers in the air. O’Hare flew like a veteran right from the start. “He just picked it up much faster than anyone else I’ve ever seen.” Thach said. “He got the most out of his airplane. He didn’t try to horse it around.”

He did particularly well in practice dogfights with the squadron’s “humiliation team.” These were exercises designed to deflate the egos of newly arrived pilots, but the tactic did not work with O’Hare. He usually came out on top, and even defeated Thach. “It wasn’t long after that,” Thach continued, “that we made him a member of the humiliation team, because he had passed the graduation test so quickly.”

The squadron got its first taste of action in February 1942 in a planned carrier strike against the Japanese-held port of Rabaul on the South Pacific island of New Britain. It was intended as a surprise attack, but the carrier task force was sighted by Japanese patrol planes before reaching the launch point and soon became the target of land-based bombers.

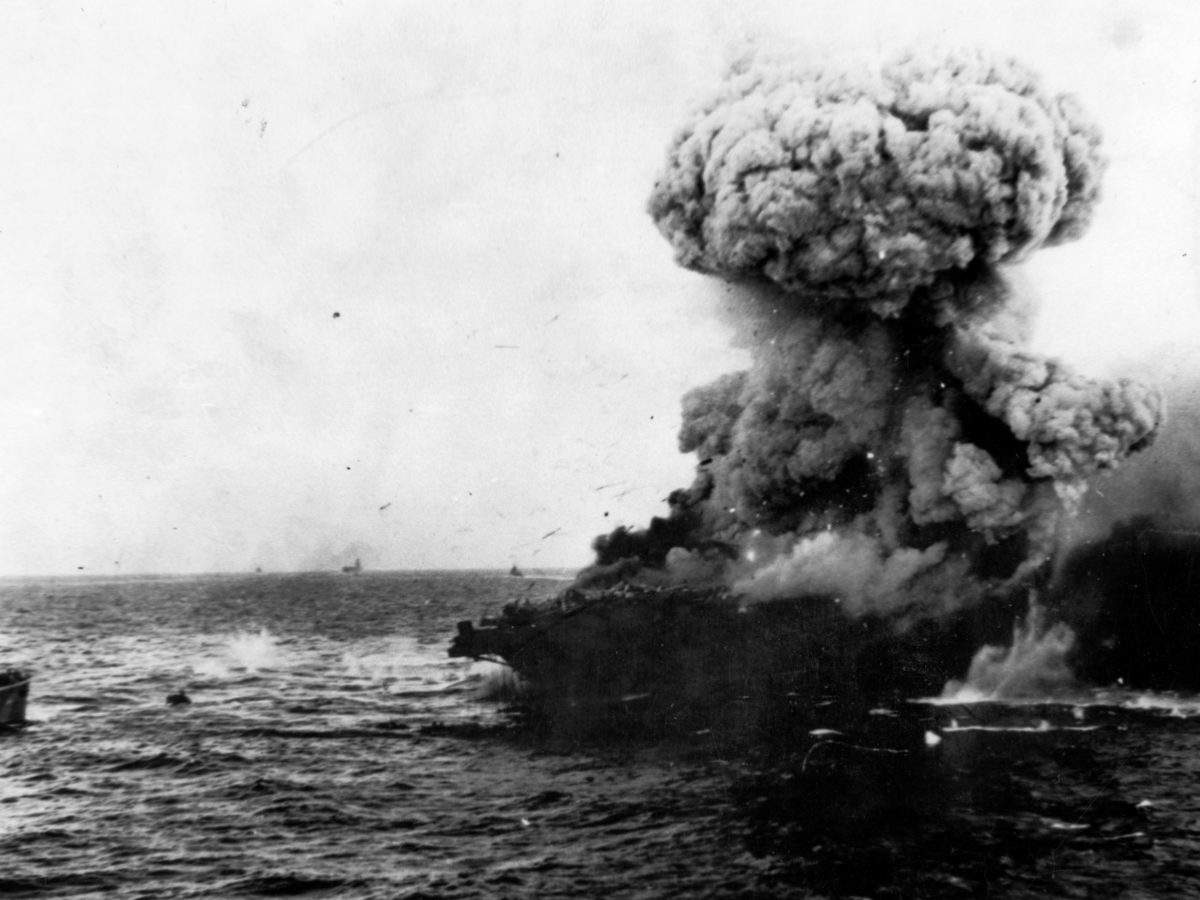

The first wave of nine twin-engined Mitsubishi G4M1 “Betty” bombers was picked up by Lexington’s radar in the mid afternoon on February 20. The six wildcats of VF-3 flying combat air patrol ripped through the formation, bringing down three Japanese planes on the first pass. Other VF-3 Wildcats then joined the fray, and the Japanese ended up losing eight of their nine aircraft without scoring a single bomb hit on the task force. The lone bomber to escape was shot down on the way home during a running fight with a Douglas SBD Dauntless dive bomber.

Meanwhile, a very frustrated Butch O’Hare was flying top cover over the fleet with his wingman, Lieutenant Marion W. Dufilho. Then Lexington’s radar picked up a second wave of “Bettys” flying in a large V formation composed of three smaller V’s and closing fast on the task force from the east. With the other Wildcat pilots still pursuing the remnants of the Japanese first wave, O’Hare and Dufilho were all that stood between the incoming bombers and the American carrier.

O’Hare and Dufilho met the enemy formation some 12-15 miles out from the task force, flying at an altitude of 11,000 feet. They flew straight at the lead section, climbing above the formation and then rolling their Wildcats for a rear attack on the trailing aircraft on the right side of the V.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

Ignoring heavy fire from the well-armed Bettys, O’Hare closed to 100 yards and sighted his guns on the starboard engines of the last two aircraft. Two quick bursts, and both engines seemed literally to jump out of their mountings, O’Hare pulled up, dodging debris from the stricken aircraft, and crossed to the other side of the formation. He then realized for the first time that his wingman was not with him. Dufilho had dropped out of the fight when his guns jammed. Unperturbed, O’Hare moved up the line, shooting down two more airplanes. Then, on his third pass, he went after the lead bomber with the master bombardier on board and sent it down in flames. He also damaged a sixth aircraft, but ran out of ammunition before he could claim another victory.

This traditional account of the engagement is somewhat disputed, however, by John B. Lundstrum’s book The First Team, a well-documented history of the Pacific campaign from Pearl Harbor to Midway. Drawing on material from Japanese sources, Lundstrom asserts that the second wave of bombers included only eight aircraft and that one of the planes shot out of the formation by O’Hare actually managed to limp back to Rabaul. O’Hare was still officially credited with five victories that day, which made him the Navy’s first ace of World War II. afterward, with characteristic modesty, he made it all sound like a simple training exercise. “It seems as if all you need to do is put some of these .50-caliber slugs into the Japanese engines and they come all apart and tear themselves right out of the ships,” he said.

The Lexington’s crew cheered as the Japanese bombers fell from the sky. Those below decks heard a play-by-play account over the ship’s loudspeaker system, being broadcast by a United Press reporter. Fellow pilots later marveled at O’Hare’s gunnery, noting that he used only about 60 rounds to shoot down each bomber.

The strike against Rabaul had to be canceled because the element of surprise had been lost, but it was a great day for naval aviation. The Navy claimed that 16 of the 18 attacking aircraft had been “splashed,” along with two four-engined patrol planes. U.S. forces lost two F4Fs but only one pilot, and the task force was undamaged. For his part, O’Hare didn’t seem to mind that he had been the target of a jumpy Navy machine-gunners he returned to the carrier. According to Thach, he walked over to the trigger-happy sailor and said gently”Son, if you don’t stop shooting at me when I’ve got my wheels down, I’m going to have to report you to the gunnery officer.” Later O’Hare expressed a certain degree of annoyance about the incident. “I don’t mind him shooting at me when I don’t have my wheels down,” he said, “but it might make me have to take a wave-off, and I don’t like to take wave-offs.”

It would be more than a year before anyone—friend or foe—would shoot at O’Hare again. By returning to Washington for the decoration ceremonies, he missed both the Battle of the Coral Sea in early May, during which the Lexington was sunk, and the pivotal battle of Midway one month later.

In June, with his public relations assignment completed, O’Hare was given command of his old squadron (redesignated VF-6). But by then most of his old squadron mates were gone, and his job was one of training new pilots rather than fighting the enemy.

As a training officer, “O’Hare preached the Bible according to Thach,” Barrett Tillman wrote in Hellcat. “Teamwork and marksmanship were the virtues he stressed.” And, like Thach, he was all business where flying was concerned. Once, when several squadron pilots wanted to try out some Army Curtiss P-40s at a nearby airfield in Hawaii, he hauled them over the coals, saying it was more important to gain experience in the new Grumman F6F-3 Hellcats that were replacing their Wildcats.

Finally, in late August 1943, O’Hare’s squadron took part in an assault by the new generation of fast carriers against Marcus Island in the Central Pacific. The American raiders achieved such complete surprise that no Japanese planes even got off the ground. However, O’Hare was awarded a Distinguished Flying Cross (DFC) for disregarding “Tremendous anti-aircraft fire” in leading his squadron “in persistent and vigorous strafing raids against hostile establishments on the island.

The squadron took part in a carrier raid on Wake Island five weeks later. The Hellcat pilots finally got to test their machines against the legendary “Zero.” O’Hare shot down one, his first kill since he bagged five in one day in February 1942. On the way home, he spotted a Betty and also sent that crashing into the sea for his seventh victory. His day’s work earned him a gold star in lieu of a second DFC.

Next came the campaign against the Gilbert Islands and the bloody Marine invasion of Tarawa. By now, O’Hare was an air group commander assigned to Enterprise. Edward P. Stafford, who wrote the ship’s history, The Big E, noted: “O’Hare was unchallengeably the best shot and the best pilot in his command. His men stood in Awe of him for the hero he was. They respected him for his warmth, his enthusiasm and his courage.

Enterprise was part of Task Group 50.2, which also included two light carriers, Belleau Wood and Monterey, three fast battleships and six destroyers. The group’s mission was to secure the airspace over Makin Atoll at the northern end of the Gilberts, destroy the island’s defense installations, support invasion forces on November 20, and then stand by to repel any Japanese counterstrike.

Resistance on both Makin and Tarawa had been crushed by November 23 (with the Marines taking more than 3,000 casualties on Tarawa). But the American Fifth Fleet of Vice Admiral Raymond Spruance was coming under increasing attack from Japanese land-based torpedo planes and submarines. On the morning of November 25, the escort carrier Liscome Bay was sunk by a Japanese submarine I-175, 20 miles southeast of Makin, with the loss of some 650 crew members. That night, a Japanese twin-engined bomber, looking for a target, crossed the deck of Enterprise at an altitude of approximately 400 feet but never saw the ship.

Now O’Hare’s top priority was to stop the Japanese torpedo planes that appeared on the ship’s radar just after sunset, dropping parachute flairs and searching for targets. “The Maps can’t attack us by day and make it profitable anymore,” he told a writer for the Saturday Evening Post. “Our Hellcats and AA [anti-aircraft] guns are too much for them …. The Maps have got the word …the only time to sock their fish home is at night when they can avoid our fighters.”

O’Hare and other senior pilots had developed a novel night-fighting tactic. They teamed up two F6F Hellcats with a radar equipped Grumman TBF Avenger torpedo-bomber and sent them out on search-and-destroy missions. First, the ship’s radar would vector the team toward the enemy. Then the TBF radar would lock onto a target and lead the Hellcats in close enough for the pilots to see the exhaust from the enemy planes’ engines and to begin shooting. Up to that point in the war, few, if any, actual combat operations had been attempted in the hours of darkness because of the difficulty in finding the enemy. If approved, O’Hare’s plan would be a naval aviation first.

Still, O’Hare was uneasy about landing his team of fighters on Enterprise after dark. He wanted an alternative. Soon November 26, he flew his Hellcat to the newly captured airfield on Tarawa. The field was still pitted with bomb craters, but he decided that it might be safer landing on a pitching carrier in the dead of night. He returned to the ship more determined than ever to try his experiment.

But first O’Hare had made his point and was given permission to run the night-fighter operation later in the day. Since it was primarily his idea, he characteristically decided to fly the first mission himself with a volunteer, Ensign Warren “Andy” Skon, as his wingman. They took off from the carrier just before sunset, and then were vectored “on a number of courses in search of bogies,” but night overtook them before they could make any contact. They turned their attention to joining up with the TBF-1C Avenger, flown by Lt. Cmdr. John L. Phillips, commander of VT-6, that had followed them off the carrier.

The join-up proved difficult in the darkness despite guidance from Enterprise’s radar controllers. There were also numerous Japanese aircraft buzzing around unseen in the night sky, but the Avenger pilot shot down two of them with the help of his onboard radar. Finally, after more than 30 minutes of searching, the rendezvous was made. The three aircraft turned on low-intensity running lights to avoid losing contact again. O’Hare flew to the starboard and slightly astern of the Avenger, while Skon took up a similar position on the port side.

In an official statement made after the engagement, Skon estimated that O’Hare was about 200 feet to the right of him when the TBF’s turret gunner suddenly opened fire with his .50-caliber machine gun. Skon thought the tracers passed between the two Hellcats, but a few seconds after the first shots, “O’Hare slid out of formation,” and Skon started to follow him down, but O’Hare was moving too fast and “disappeared from sight.” Radio calls to the missing pilot went unanswered. The TBF gunner later stated that he saw a “fourth plane closing in on us,” and was given permission to open fire as soon as it was in range. Although it was very dark and he was blinded by his own tracer fire, he thought he hit his target but couldn’t say if he “shot down the Jap.” The radar officer supported the gunner’s story about a forth aircraft but said nothing about having another target on his scope.

The report filed by the TBF commander raised further doubts about the accuracy of the gunner’s observations. It noted that the “turret gunner was blinded by his own and the enemy tracers and had great difficulty in seeing the target.” In addition, he said, “the field of vision through the electrical turret sight was very limited,” and recommended the use of “auxiliary sights in future night work.”

Ensign Skon, perhaps the only impartial observer, had his own version of O’Hare’s fate. “I at no time sighted a second plane to the starboard and astern of the TBF,” he said. Nor did he “observe a plane pass over the TBF after Lt. Cmdr. O’Hare slid out of formation.” He also stated that he “saw no gunfire other than the TBF turret gunner’s.”

O’Hare was awarded the Navy Cross for his final action. One year later, he was declared officially dead, although his accomplishments continued to serve as an inspiration for Navy fliers throughout the war. In September 1949, the city of Chicago made sure his heroism would never be forgotten. The name of the city’s airport was changed from Orchard Field to O’Hare Airport.

On February 20, 1992, Butch O’Hare’s Medal of Honor was presented to the city of Chicago by his daughter and two sisters during a commemorative ceremony. The event marked the 50th anniversary of what the citation called “one of the most daring, if not the most daring single actions in the history of combat aviation.” It is now part of the O’Hare memorial exhibit at the airport that bears his name.

John G. Leyden is a Navy veteran and retired employee of the Federal Aviation Administration, serving as the news director in the FAA’s Public Affairs Office. For further reading: Queen of the Flat-Tops, by Stanley Johnson; The First Team, by John B. Lundstrom; and The Big E, by Edward P. Stafford.