A stubby little U.S. Navy fighter did yeoman duty when times were toughest early in World War II.

‘It was not as you remember it, Saburo. I don’t know how many Wildcats there were, but they seemed to come out of the sun in an endless stream. We never had a chance….Every time we went out we lost more and more planes. Guadalcanal was completely under the enemy’s control….Of all the men who returned with me, only Captain Aito, [Lt. Cmdr. Tadashi] Nakajima and less than six of the other pilots who were in our original group of 80 men survived.’

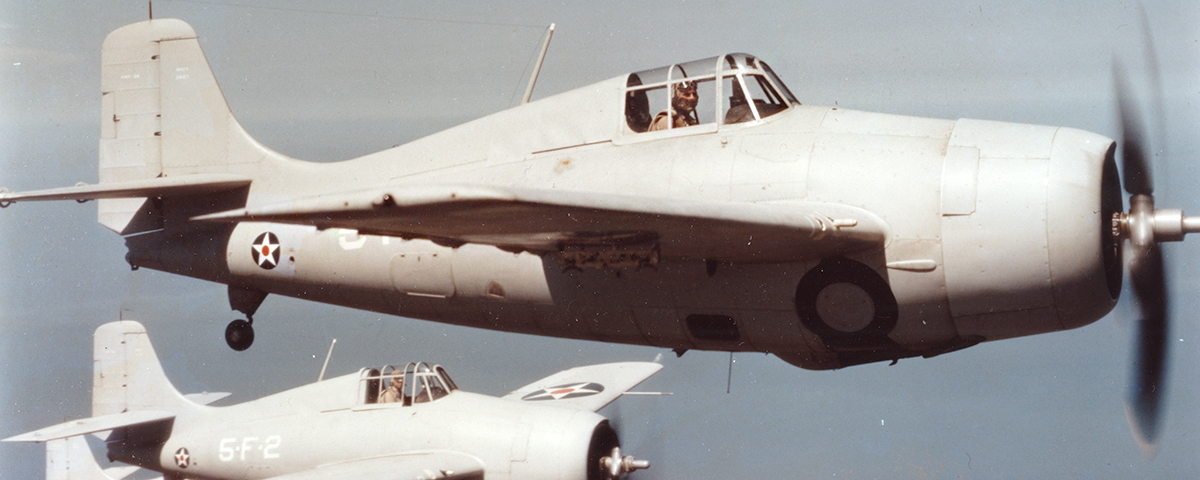

Those words of top Japanese ace Hiroyoshi Nishizawa, part of a November 1942 conversation that was reported in fighter pilot Saburo Sakai’s autobiography, Samurai, might be the best tribute ever paid to the Grumman F4F Wildcat. While the newer Vought F4U Corsairs and F6F Hellcats grabbed the spotlight, it was the Wildcat that served as the U.S. Navy’s front-line fighter throughout the early World War II crises of 1942 and early 1943.

The Wildcat is unique among World War II aircraft in that it was originally conceived as a biplane. By 1936, the Navy had drawn up specifications for its next generation of shipboard fighters. Although presented with ample evidence that the era of the biplane was over, a strong traditionalist faction within the Navy still felt the monoplane was unsuitable for aircraft carrier use.

As a result, on March 2, 1936, Grumman was ordered to develop yet another single-seat biplane, the G-16, to replace the successful F3F biplane series. The design, the XF4F-1, was ordered both to placate the traditionalists and to be a backup for the Navy’s first monoplane, the Brewster F2A Buffalo. Grumman engineers, however, showed that the installation of a larger engine in the F3F would result in performance comparable to that expected from the new design, and began work on a parallel monoplane project, the G-18 (or XF4F-2). The Navy finally saw the logic of Grumman’s actions and officially sanctioned them.

Although redesigned as a monoplane, the XF4F-2 that rolled out of Grumman’s Bethpage, Long Island, assembly shed on September 2, 1937, showed a strong family resemblance to the F3F family with narrow-track landing gear that retracted upward and inward into the barrel-shaped fuselage. That, in combination with the placement of the cockpit high on the fuselage to give good vision, helped give the Wildcat its distinctive, pugnacious appearance.

Although the new ship was not a true ‘aerobatic’ performer, it was stable and easy to fly and displayed excellent deck-handling qualities. One problem that would remain with the F4F throughout its life, however, was its manual landing gear retraction mechanism. The gear required 30 turns with a hand crank to retract, and a slip of the hand off the crank could result in a serious wrist injury.

The prototype F4F had to best two competitors during spring 1938 trials before its acceptance by the U.S. Navy–the prototype F2A and a naval version of the Seversky P-35. Although the F2A was judged the winner because of teething problems encountered with the F4F, the Navy saw enough potential in the design to order continued development incorporating a newly designed Pratt & Whitney R-1830 radial engine with a two-speed supercharger.

The resulting redesign, the XF4F-3, differed from the original in several respects. Longer-span wings with squared tips–later a Grumman trademark–were added, and the armament of four .50-caliber machine guns was concentrated in the wings. Weight, however, had crept up to 3 tons. First flight for the new machine was February 1939, about two months after the first flight of the Mitsubishi A6M1 Zero prototype in Japan.

International tensions were rising, and the Navy awarded Grumman a contract for 600 Wildcats by the close of 1940. Enough of them were received to begin operations from the carriers Ranger and Wasp by February 1941.

First combat for the F4F was not with the U.S. Navy but with Britain’s Royal Navy, and its first victim was German. The British had shown great interest in the Wildcat as a replacement for the Gloster Sea Gladiator, and the first were delivered in late 1940. On Christmas Day 1940, one of them intercepted and shot down a Junkers Ju-88 bomber over the big Scapa Flow naval base. The Martlet, as the British also called it, saw further action when 30 originally bound for Greece were diverted to the Royal Navy following the collapse of Greece and were used in a ground attack role in the North African Desert throughout 1941.

The Wildcat’s American combat career got off to a more inauspicious start. Eleven of them were caught on the ground during the December 7, 1941, Pearl Harbor attack, and nearly all were destroyed. It was with Marine squadron VMF-211 at Wake Island that the Wildcat first displayed the tenacity that would bedevil the Japanese again and again. As at Pearl Harbor, the initial Japanese attacks left seven of 12 F4F3s wrecked on the field. But the survivors fought on for nearly two weeks, and on December 11, Captain Henry Elrod bombed and sank the destroyer Kisaragi and helped repel the Japanese invasion force. Only two Wildcats were left on December 23, but the pair managed to shoot down a Zero and a bomber before being overwhelmed.

Carrier-based F4F3s engaged the enemy soon after. On February 20, 1942, Lexington came under attack from a large force of Mitsubishi G4M1 Betty bombers while approaching the Japanese base at Rabaul. The F4F fighter screen swarmed over the unescorted bombers, and Lieutenant Edward H. ‘Butch’ O’Hare shot down five of them. He was awarded the Medal of Honor and became the first Wildcat ace.

During the Coral Sea battle in May, F4Fs from the carriers Lexington and Yorktown inflicted heavy losses on the air groups from Shokaku, Zuikaku and Shoho but could not prevent the sinking of Lexington. While the air battles were by no means one-sided, they were clearly a shock to many Zero pilots, who had faced little serious opposition up to that time.

By the time of the Midway engagement in June, the fixed-wing F4F-3 had been replaced by the folding-wing F4F-4. Although the new wings enabled the carriers to increase their fighter complement from 18 to 27, the F4F-4’s folding mechanism, coupled with the addition of two more machine guns, raised its weight by nearly 800 pounds and caused a falloff in climb and maneuverability.

Nearly 85 Wildcats flew from Yorktown, Enterprise and Hornet during Midway, but it was the Douglas SBD Dauntless dive bomber that was destined to be the hero of the battle, sinking the carriers Akagi, Kaga, Hiryu and Soryu, and dealing the Imperial Navy a disastrous defeat.

When news of the U.S. invasion of Guadalcanal reached the Japanese on August 7, 1942, they launched airstrikes from Rabaul. Flying escort was the elite Tainan Kokutai (air group), which counted among its pilots Sakai (64 victories), Nishizawa (credited with 87 before his death in October 1944) and other leading aces. But over Guadalcanal, the Zeros were off-balance from the start. Their first glimpse of the new enemy came when Wildcats of Saratoga‘s VF-5 dived into their formation and scattered it.

Sakai and Nishizawa recovered and claimed eight Wildcats and a Dauntless between them, but they were the only pilots to score. The Navy F4Fs, in return, brought down 14 bombers and two Zeros.

Although exact Japanese losses over Guadalcanal are not known, they lost approximately 650 aircraft between August and November 1942–and an irreplaceable number of trained, veteran airmen. It is certain that the F4Fs were responsible for most of those losses. During the Battle of Santa Cruz on October 26, 1942, Stanley W. ‘Swede’ Vejtasa of VF-10 from the carrier Enterprise downed seven Japanese planes in one fight. Marine pilot Joe Foss racked up 23 of his 26 kills over Guadalcanal; John L. Smith was close behind with 19; and Marion Carl, Richard Galer and Joe Bauer were among other top Marine aces.

A large part of the Wildcat success was tactics. The agile Zero, like most Japanese army and navy fighter craft, had been designed to excel in slow-speed maneuvers. U.S. Navy aviators realized early on that the Zero’s controls became heavy at high speeds and were less effective in high-speed rolls and dives. Navy tacticians like James Flatley and James Thach preached that the important thing was to maintain speed–whenever possible–no matter what the Zero did. Although the Wildcat was not especially fast, its two-speed supercharger enabled it to perform well at high altitudes, something that the Bell P-39 and Curtiss P-40 could not do.

The F4F was so rugged that terminal dive airspeed was not redlined. The A6M2’s 7.7mm cowl guns and slow-firing 20mm cannons were effective against an F4F only at point-blank range. But F4F pilots reported that hits from their .50-caliber wing guns usually caused complete disintegration of a Zero.

The Zero and Wildcat shared one serious liability, though. Neither could be modified successfully to keep pace with wartime fighter development. It was determined that the F4F airframe could not accommodate a larger engine without an almost complete redesign, which ultimately did take shape as the new 2,000-hp F6F Hellcat.

The Wildcat’s air combat role began to wane when the Chance-Vought F4U Corsair arrived at Guadalcanal in February 1943. Nevertheless, the stalwart F4F was still the front-line fighter when Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto launched Operation I-Go against Allied forces in the Solomons in April, and Marine Lieutenant James Swett shot down seven (and possibly eight) Aichi D3A1 Val dive bombers in a single combat.

As 1943 wore on, the Wildcat gradually was relegated to a support role as the F6F replaced it aboard fleet carriers. The F4F’s small size, ruggedness and range–enhanced by two 58-gallon drop tanks–continued to make it ideal for use off small escort carrier decks. The little warrior–in both U.S. and Royal Navy markings–contributed to eliminating the U-boat menace in the Atlantic.

A General Motors built version of the F4F received a marginal boost when a Wright 1,350-hp single-row radial was installed in place of the 1,200-hp Pratt & Whitney. The first production models of the new variant, designated the FM-2, arrived in late 1943. The FM-2’s new engine, coupled with a 350-pound weight reduction, produced improvements in performance over the F4F. In fact, postwar tests revealed the late-model A6M5 Zero to be only 13 mph faster.

FM-2s were normally teamed with TBF Avengers in so-called VC ‘composite’ squadrons on small escort carriers. During the Battle of Samar on October 25, 1944, FM-2s and Avengers from several ‘baby flattops’ aided destroyers in disrupting an overwhelming Japanese battleship task force that surprised the American invasion fleet off the Philippines. The aircraft, although handicapped by a lack of anti-shipping ordnance, so demoralized the Japanese that a potential American disaster was averted.

Although opportunities for air combat were few, FM-2s notched a respectable 422 kills–many of them kamikaze aircraft–by the end of the war. On August 5, 1945, a VC-98 FM-2 from USS Lunga Point shot down a Yokosuka P1Y1 Frances recon bomber to score the last Wildcat kill of the war.

In terms of sheer numbers, the F4F’s kill tally was less than the Corsair and much less than the Hellcat. But the Hellcat did not appear until the really critical combats were long over; it was the underdog F4F, flown by highly skilled U.S. Navy and Marine pilots, that provided the few sparks of victory early in the war, when the Japanese onslaught in the Pacific seemed overwhelming.

Many aircraft achieved greatness during World War II, but few could be called heroic. The F4F Wildcat, usually outnumbered and outclassed by its opponents, was a heroic airplane.

Written by Bruce L. Crawford, this article was originally published in the May 1996 issue of Aviation History. For more great stories subscribe to Aviation History today!