Like the barrage balloon and the assault glider, the torpedo bomber is a weapon we will never see again. Its fate had been sealed nearly four decades earlier, but the brief 1982 Falklands War showed that ship-killing missiles such as the Exocet could achieve more than an entire air wing of World War II torpedo bombers. And they could accomplish their mission at near-supersonic speeds from stand-off range. Today, nobody needs airplanes launching submersible motorboats while flying at the speed of a fast car.

The ultimate torpedo bomber

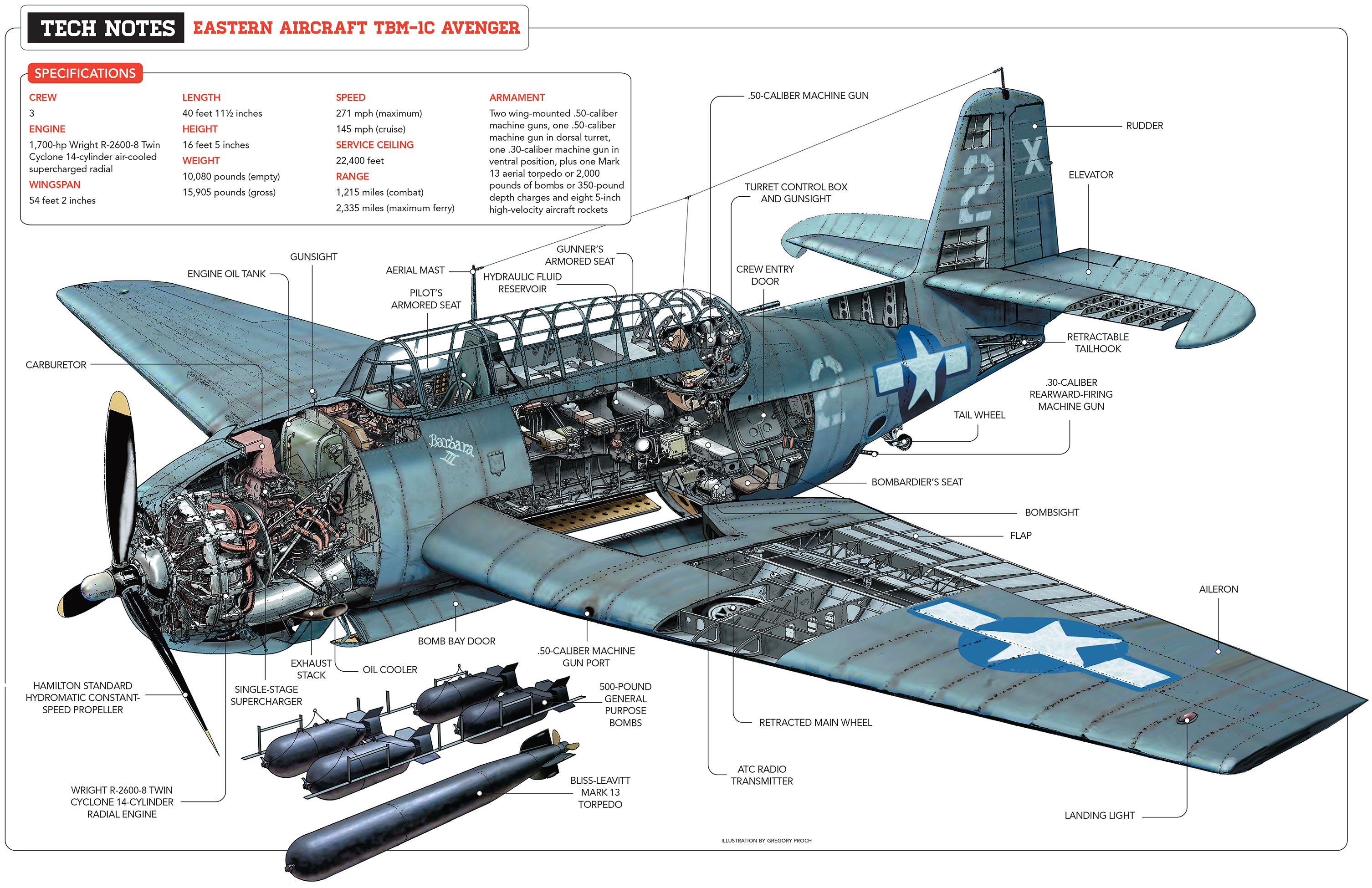

The torpedo bomber’s glory days, when German capital ships and entire Italian fleets were being torpedoed in the European theater while the Japanese lost their precious aircraft carriers in the Pacific, lasted from 1940 to late ’42. Yet the Grumman TBF Avenger, the finest torpedo bomber to fly in any war, lived on far beyond its star turn. As surface ship targets disappeared, Avengers began dropping more bombs than torpedoes, and the airplane developed new roles as WWII progressed: anti-submarine hunter-killer, convoy guardian, close air support attack aircraft, radar platform, airborne early-warning sentry, long-range reconnaissance patroller and ultimately that most utilitarian of roles, carrier onboard delivery truck. The big Grumman had the substantial bomb bay, unusually spacious interior, multiple seats and excellent performance to get away with it.

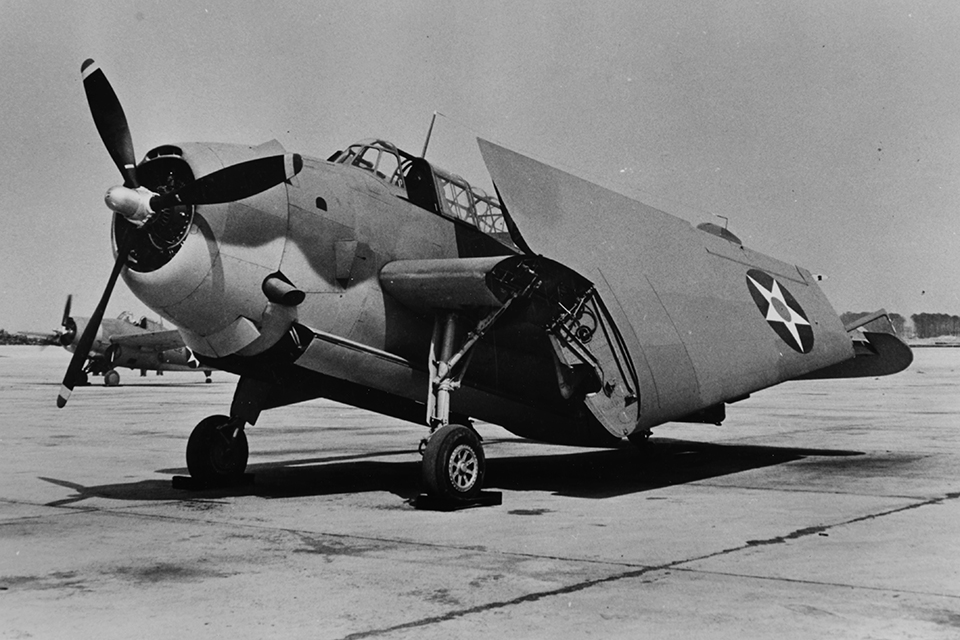

Though it may not be obvious, this beast of an airplane was a supersized version of the F4F Wildcat. Both were midwing, barrel-bodied, hell for stout warplanes with surprising performance even though they were often characterized as underpowered. The Avenger introduced carrier aviation to Grumman’s remarkable Sto-Wing system, enabling an airplane to fold its wings alongside its body like a bird. Sto-Wings were quickly fitted on the Wildcat as well, beginning with the F4F-4 version. On the Avenger they narrowed the wingspan from 54 feet 2 inches to just over 18 feet and eliminated the need for extra overhead room on a carrier’s hangar deck.

Folding wings and paper clips

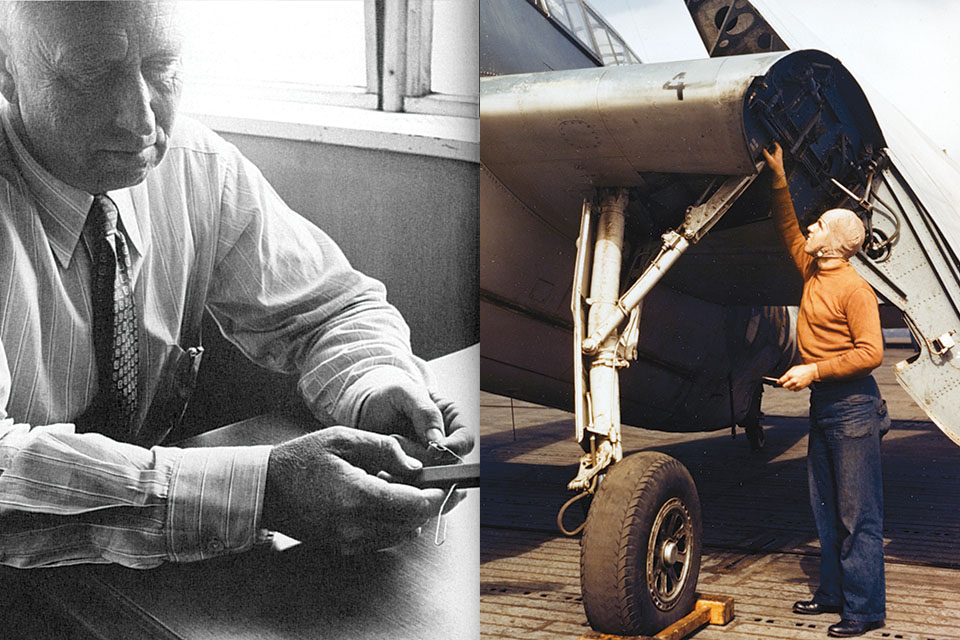

Leroy Grumman came up with the Sto-Wing by fiddling with a draftsman’s eraser to represent a fuselage and paper clips stuck into it as wings. He hit on what’s called a skewed axis—a fixed pivot point on the wing root that allowed the Avenger’s wings to simultaneously rotate and fold. The Sto-Wing remained a feature of many Grumman aircraft right up to the E-2 Hawkeye.

Though it’s clear who invented the Sto-Wing, naming the designer of the Avenger is more difficult. Some say it was Roy Grumman, others vote for company cofounder and chief engineer William Schwendler. But the man in the trenches seems to have been engineer Robert Hall, a former air racer and designer of several of the Granville Brothers Gee Bees. An all-rounder, Hall also made the Avenger’s first flight on August 7, 1941.

With a maximum takeoff weight of 17,893 pounds, the Avenger was the biggest single-engine airplane produced during WWII by any combatant. It outlifted the heaviest P-47 Thunderbolt by just shy of 400 pounds. The Avenger’s bomb-bay load was a neat ton: a 2,000-pound torpedo or four 500-pound bombs.

Among pilots, the corny joke about the Avenger was that it was so heavy it could fall faster than it could fly. Certainly during takeoffs from escort carriers this often felt true. Bombed-up Avengers had to be catapulted, but an escort carrier’s catapult was only 45 feet long and the best the ship could do into the wind was 19 knots. “We would come off the catapult at 90 knots—barely flying speed,” recalled turret gunner James Gander. “We would dip down when we left the deck until we got our speed up.” The airplane’s ponderous performance in comparison to the Wildcat led escort carrier crews to nickname it the “Turkey.”

The Avenger had no underwing ordnance hardpoints, but it did soon get launch rails for HVARs—high-velocity aircraft rockets, four under each wing. They were potent missiles, providing the airplane with the firepower of a destroyer’s broadside. In fact the rockets often had heavy, solid-metal warheads, designed to punch through a submarine’s hull simply with the power of inertia. Despite the rockets being unguided, Avenger pilots quickly became adept at drilling explosive HVARs deep into Japanese caves.

The most common myth about the Avenger is that it made its first public appearance on December 7, 1941, and was that day immediately given its retaliatory name. In fact the airplane had been named in early October, two months before anybody planned on avenging Pearl Harbor. The first production Avenger came off the line on January 3, 1942—the first new American aircraft design to enter the war.

Baptism by fire … and disaster

Its combat debut was a disaster. Six TBF-1s of torpedo squadron VT-8, relayed from the carrier Hornet to Midway Atoll, attacked the Japanese fleet on June 4, 1942. Only one returned, shot to pieces, its turret gunner dead and radioman wounded. The Navy began having second thoughts about its new torpedo plane.

But the big Avenger recovered quickly as its pilots gained experience. Three months later, in the Battles of the Eastern Solomon Islands and Guadalcanal, Avengers sank the light carrier Ryujo and the battleship Hiei. Ultimately, Avengers were involved in the sinking of 12 carriers, six battleships (including the superships Yamato and Musashi), 19 cruisers, 25 destroyers and 30 submarines in the Pacific and Atlantic.

Most Avengers were manufactured by General Motors, not Grumman. GM had established a division called Eastern Aircraft using five empty car factories in the Northeast. It took over Avenger production when Grumman found itself overwhelmed by the need to crank out the new F6F Hellcat. Grumman built almost 3,000 TBFs; GM’s 7,500-some were designated TBMs. (Think M for Motors and you’ll never confuse the two.)

“What followed was the clash of two worlds,” wrote David Doyle in his book TBF/TBM Avenger. “GM started out with the idea that it would show…Grumman how to mass produce airplanes. Grumman started out with the idea that GM would be lucky if it managed to produce one airplane. GM was more wrong than right. Grumman was more right than wrong.”

Automobiles and airplanes are both complex machines, but they have vastly different production requirements. Cars could be churned out by the thousands on ceaseless production lines, while airplanes were produced through a stop-and-go method. Weight didn’t matter much with pre-EPA cars but was crucial for airplanes. Aircraft tolerances were tight, cars could deal with quarter-inch panel gaps. Modifications during production were common with airplanes, rare with cars.

Grumman facilitated the process by delivering to Eastern the “P-K airplane”—a TBF assembled entirely with sheet-metal screws made by the Parker-Kalon Corporation, so the airplane could be disassembled and reassembled until GM’s operators got it right.

The Avenger was unique in having an electrically operated gun turret designed by Grumman rather than one bought from Sperry, Bendix, Erco or other specialists. Such turrets were mechanically or hydraulically operated and were less than precise in movement. The Grumman turret was designed by the company’s sole electrical engineer, Oscar Olsen, who came up with the idea of using amplidynes—electromechanical amplifiers commonly used to rotate huge naval gun turrets. Miniaturized by GE at Olsen’s request, amplidynes turned out to be excellent at providing rapid and consistent movement for the Avenger’s big “goldfish bowl,” as gunners called it. When Olsen told Bill Schwendler of his idea, Schwendler said he hoped it worked, since they would otherwise have a four-foot hole in the airplane with nothing to fit into it.

![A TBF-1C of VT-6 catches a wire aboard Intrepid during operations in the central Pacific. (PF-[Aircraft]/Alamy)](https://www.historynet.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/Avenger-Trap-960_640.jpg)

An Avenger turret gunner didn’t hammer away at the enemy behind a set of spade grips, comic-book style. He sat alongside his .50-caliber machine gun, its breech next to his left ear, controlling the turret’s motion and the gun’s firing with a pistol-grip handle.

Actor Paul Newman, who joined the Navy intending to be a pilot but flunked the preflight physical because of color blindness, ended up as a radioman and gunner in Avengers. How Newman later achieved international fame as an automobile racer, in a sport that depends heavily on colored signal lights and flags, is a question that flight surgeons have never answered. Though often described as a turret gunner, Newman controlled the single ventral .30-caliber stinger mount from his station in the rear fuselage.

It has been variously written that the stinger gunner fired from a standing position, or while kneeling or laying prone. We asked the curator of Long Island’s Cradle of Aviation Museum, 10 minutes’ drive from the site of the original TBF factory, to climb into the museum’s restored Avenger and see what he thought. “The gunner would have sat with his legs straddling the gun, or possibly kneeling,” replied Joshua Stoff. “He definitely couldn’t have stood, and if lying down, I don’t see how he could have elevated and depressed the gun. Either way, visibility for the gunner was poor—only down and to the rear. But the belly is pretty roomy for one person, even with all the radio equipment installed.”

Roomy indeed. Some Avengers were used as squadron hacks, often flown between naval air stations and nearby party towns. A “designated driver” named Wellington Smith holds the record for cramming 17 pilots, plus himself, into a TBM for a flight from Holtville, Calif., back to nearby Naval Air Facility El Centro.

Late in the war, as Avengers increasingly attacked ground targets, radiomen/gunners were dropped from flight crews. Trapped in the unarmored belly, they were vulnerable to even rifle fire from the ground, and the death and injury rate for radiomen soared.

The turret was entered from below, the gunner climbing up into the fishbowl from the radioman’s compartment while facing forward, then squirming around to face aft in the seat while maneuvering a heavy plate of armor. Bailing out meant reversing the process, the gunner then finding his parachute in the compartment below and clipping it onto his harness, forcing the big entry door open against the slipstream and, along with the radioman, jumping out. Neither crewman had the space to otherwise wear a chute, though the pilot did. Not surprisingly, pilots usually survived a bailout while crewmen went down with the ship. Many Avenger crewmen say they have never heard of a turret gunner successfully bailing out.

Early Avengers had a seat between the cockpit and the turret, a few of them fitted with basic flight controls, but it was rarely occupied in combat unless a photographer or observer was along for the ride. The seat was soon gone, the space taken up by bulky 1940s radios and radar electronics, though most restored Avengers have reverted to the third seat for passengers.

A Presidential connection

History’s most famous Avenger pilot was future president George H.W. Bush. Barely 18 and a high school graduate (he would attend Yale only after the war), the 6-foot-2 Bush was one of the tallest pilots in the Navy and for a long time assumed to be its youngest aviator, an honor that actually accrued to one Charles Downey.

Bush was by all accounts an excellent pilot. He logged 1,228 hours of Avenger time, flew 58 combat missions and made 126 traps, all of them successful, aboard the short-decked light carrier San Jacinto. WWII carriers all had straight decks, so once an Avenger pilot committed to landing he either caught a wire—there were only three on San Jacinto—or ran into the crash barrier near the bow. Relying on that heavy-duty net often involved crashing into aircraft parked just beyond it. There was no such thing as a bolter, or go-around, as there is aboard a modern, angled-deck carrier.

On small carriers, picking up the no. 2 wire—the safest procedure—banged an Avenger down atop the aft elevator, which, according to author Barrett Tillman, “tilted the elevator forward and resulted in a four- or five-inch ‘curb’ for the wheels to hit.” The result often was a blown tire or two.

Bush went through three TBMs: Barbara, Barbara II and Barbara III. He safely ditched the first one after losing oil pressure during a catapult launch and being denied permission to re-land by a landing signal officer busy retrieving other Avengers. On September 2, 1944, while bombing a well-defended radio installation on the tiny island of Chichi Jima, he bailed out after Barbara II’s engine was hit and caught fire. This time he lost his crew, a fact that tortured him the rest of his life.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

The British enthusiastically adopted the Avenger for its Fleet Air Arm early in 1943, giving legendary Royal Navy test pilot Eric “Winkle” Brown the opportunity to fly it frequently. Brown found that the Avenger’s one aeronautical failing was that it spun rapidly and dangerously if anti-spin controls weren’t immediately exerted. (The airplane was placarded against intentional spins.)

Bombing with an Avenger required a steep glide-bomb approach. Brown noted the pullout was “a two-handed, somewhat frenetic affair, one hand pulling [the stick] with all its strength and the other retrimming frantically.” But the Avenger “stabilized almost immediately, a characteristic that was crucially important if a clean and accurate drop was to be achieved.” Brown also considered carrier landings out of a very stable 78-knot approach, with good visibility over the nose, “extremely easy…about as easy as that difficult art is ever likely to be.”

Many Avengers carried Norden bombsights, which were soon found to be useless. The Norden was intended for high-altitude, level bombing and it couldn’t handle the slant ranges it was being asked to compute. Bureaucracy and inertia led the Navy to continue supplying Avengers with dead-weight Nordens, and ultimately three-quarters of Norden’s production went to the sea service. The bombsights were linked to an autopilot system called Stabilized Bombing Approach Equipment that Avenger pilots found they could at least use on long flights, bypassing the unpleasantly heavy flight controls.

An Avenger’s multitasking radioman/ventral gunner was also intended to be the airplane’s bombardier. At the forward end of his cramped compartment was a small, slanted window that peered into the dark bomb bay. When the bay doors opened, the window provided a view down and ahead, between the racks of bombs. If a torpedo was in place, there was nothing to see but the top of the tin fish. So torpedo drops were controlled by the pilot, eyeballing his heading, airspeed, altitude and distance to the target, aided by a “torpedo director”—a reflector gunsight—atop the instrument panel.

Only the pilot could control torpedo release, though the crewman in the belly compartment had inflight access to the bomb bay and could change the torpedo’s depth setting. Either the pilot or the bombardier could open the bomb-bay doors, electrically or manually. The torpedo’s release switch was atop the pilot’s joystick. There was also a manual T-handle emergency release.

Bombing, however, was supposed to be in the hands and eyes of the bombardier and his magical Norden, sighting through that aslant window. The bombardier was also responsible for arming the bombs before the drop and for setting the intervalometer—a device that controlled the timing of the four bombs’ release. They could all be dropped at once, but releasing them as a spaced-out stick gave better coverage and a greater chance of at least one bomb hitting a small target.

The Avenger’s most media-worthy moment was the epic of Flight 19, five TBMs that departed on a basic bombing and navigation training flight over the Atlantic on December 5, 1945. The exercise couldn’t have been simpler: take off from Naval Air Station Fort Lauderdale, fly straight east and drop some practice bombs, turn north and fly awhile, turn due west until you hit the U.S. coast, go south and land back at Fort Lauderdale. Three left turns with all of Florida to hit.

The Grummans found themselves over the Bahamas, as they should have been, but for unknown reasons the pilots decided the islands were the Florida Keys. It didn’t help that they were flying a very basic time-speed-distance exercise yet the clocks had been removed from every one of Flight 19’s Avengers—a not uncommon bit of pilferage by people who had access to cockpits, since eight-day aircraft clocks were quickly removable and made nifty souvenirs.

Flight 19 ended up flying northwest from what they thought were the Keys. Five airplanes and 14 crewmen soon disappeared forever into the Atlantic, as did the 13-man crew of a Martin PBM-5 Mariner sent out to search for them. A tanker steaming in the area reported a huge explosion in the distance, so it was assumed the gas-heavy PBM had suffered the consequences of a fuel leak. The cause of the Avengers’ disappearance has never been definitively determined, though they undoubtedly ran out of fuel.

A 1952 Florida magazine article about the loss of Flight 19 suggested they had fallen prey to a mysterious airplane-eating, ship-sinking stretch of ocean that the author dubbed the Bermuda Triangle. Thus the Avenger came to play its part among the world’s more popular conspiracy theories, alien-abduction plots and tinfoil-hat ruminations.

The Navy’s last torpedo bomber was the Douglas A-1 Skyraider—the immortal Spad of Vietnam War fame. On May 2, 1951, early in the Korean War, eight Skyraiders made the world’s last-ever surface torpedo attack, against the Hwacheon Dam. Eight Mark 13 torpedoes were dropped, seven hit the dam and six exploded, crippling the structure for the rest of the war.

It was truly the end of an era.

For further reading, contributing editor Stephan Wilkinson recommends: Avenger at War, by Barrett Tillman; TBF/TBM Avenger, by David Doyle; Flight of the Avenger: George Bush at War, by Joe Hyams; and Looking Backward: Don Banks – One TBF Turret Gunner’s Story, by Stephen A. Banks.

This feature originally appeared in the September 2021 issue of Aviation History. Don’t miss an issue subscribe!

Ready to add this iconic bit of aviation history to your collection? Check out our exclusive modeling column and build your own!