AS CHRISTMAS APPROACHED in 1942, a young cryptographer named Leo Marks sat in an office on Baker Street in London, trying to understand what was bothering him. Marks worked for the Special Operations Executive (SOE), the clandestine outfit Prime Minister Winston Churchill had ordered to “set Europe ablaze” with sabotage operations. His job was to improve the security of communications with agents behind enemy lines who transmitted and received encrypted messages in Morse code via portable radio sets.

There were plenty of things to trouble the 22-year-old: he seemed to be on the point of being fired for insubordination, he couldn’t get a girlfriend, and his neighbors believed his lack of a uniform meant he was a coward. But it wasn’t any of those things that were on his mind. It was something about the messages SOE was getting from its agents in the Netherlands.

For a start, some weren’t using their security checks. Agents were given secret signals—often a deliberate spelling mistake—to include in a message to show that they weren’t “controlled”: that they hadn’t been captured and forced to transmit at gunpoint. Typically agents would be given two such checks: one they could confess to under torture and one they were supposed to keep secret. One Dutch agent had never used any of his checks; another had started out doing so and then stopped. That ought to have been a red flag, but when Marks asked the Dutch section’s controllers about it, he was told not to worry.

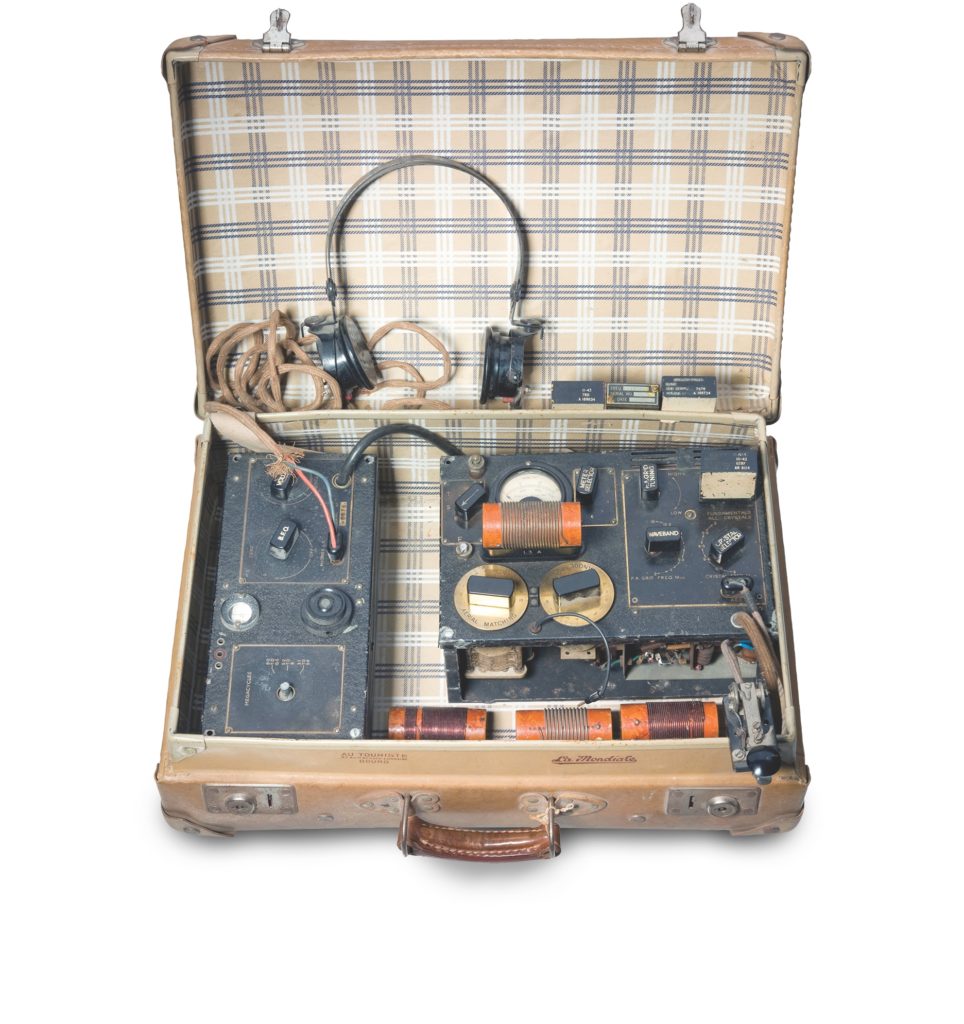

Part of the trouble was that all of SOE’s communications security was lax. Marks had been horrified, on joining earlier that year, at how easy the organization’s ciphers were to break. That made the main part of his job particularly important: ensuring that the agents spent as little time as possible on the air. Once an agent began transmitting, Nazis using direction-finding equipment would start hunting for the signal’s source. If caught, the agent faced torture and death. One cause of extra transmissions was when an agent made an encoding error, meaning that the message couldn’t be decoded at the other end. Until Marks arrived, SOE had tended to ask agents to send their message again. But Marks viewed that as an unnecessary risk. He set about teaching SOE’s signals staff how to work out where the agent had gone wrong and decode their messages so they didn’t have to retransmit.

Although, when Marks thought about it, this was one problem the Dutch agents didn’t have. Their messages were always perfectly encrypted. It would be several weeks before he realized the significance of that.

SOE agents (in Greece, top) communicated with their handlers via encrypted messages sent on portable radio sets (below)—an act that put them at risk. The longer an agent was on the air, the more likely it was the Nazis could find the signal’s source. ( © Private Collection (HU 102108) )

double-crossed

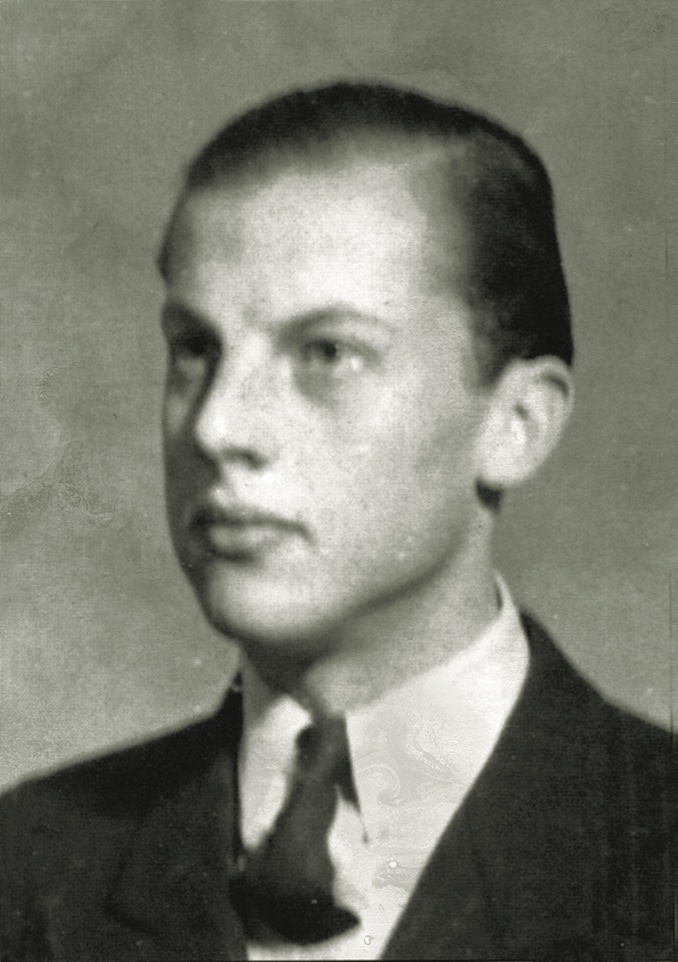

OVER IN HOLLAND that Christmas, another young man had no doubt at all that there was a problem with SOE’s operation. His name was Johan Ubbink, a 21-year-old SOE radio operator, and he was in a German-controlled prison.

Ubbink—codenamed “Chive” by SOE, which gave many of its Dutch operatives vegetable code names—had already had a lively war, starting out as a Dutch naval officer before making his way to England via Sweden, Russia, Iran, and India. In Britain, he’d been recruited as an agent, and at the end of November 1942 he and a fellow Dutchman

had parachuted into the Netherlands on a mission to organize local resistance to the Nazi invaders into a “secret army” ready to support Allied plans to liberate the Continent.

On the ground, Ubbink and his companion had been met, as planned, by a local “reception committee” of six Dutchmen. They wanted him to hand over his pistol, as it would be impossible to explain if he were stopped by a German patrol. With some reluctance, Ubbink agreed. After an exchange of gossip, he was told it was time to set off for their hideout. “Then we were suddenly seized from behind,” he said later. The reception committee was in fact a group of Dutch policemen working for the Nazis.

When the Germans interrogated him, the experience was friendlier than Ubbink expected. He was given coffee and cigarettes. At first, he refused to give more than his name, age, and place of birth. But his interrogator replied that they already knew everything, offering a detailed rundown of the sites where Ubbink had been trained, his instructors, and his fellow students. Every agent sent to Holland had been captured, the interrogator said. It was at this point that Ubbink cracked: what was the point of holding out against people who knew so much? Over the next few days, deprived of sleep, he gave up most of what he knew, including his radio code.

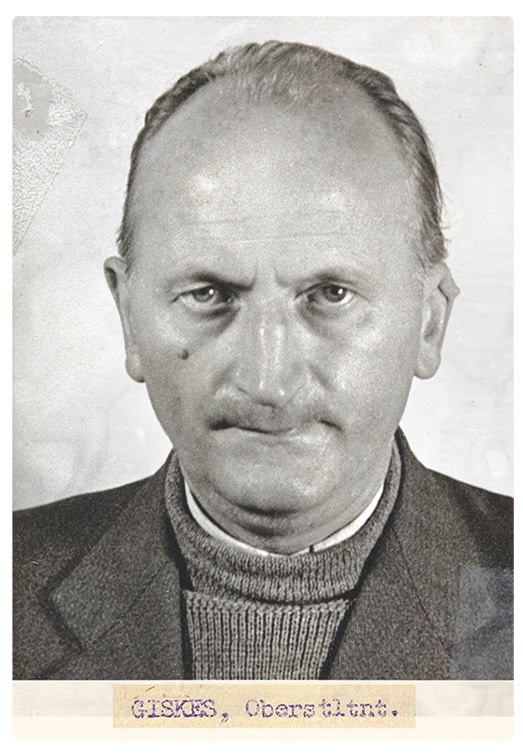

Ubbink’s interrogator wasn’t bluffing when he said that the entire Dutch SOE operation was in Nazi hands. It had been for months. Hermann Giskes—a 46-year-old veteran of the Great War who had spent many of the years since in his family’s tobacco business—was the top operative in Holland for Germany’s military intelligence organization, the Abwehr. In late 1941 Giskes’s subordinates told him about an informant who had reported that the British were sending supplies to the Dutch resistance. He was initially skeptical: “Go to the North Pole with your stories,” he scoffed. But Giskes’s men persuaded him the source was right, and the ensuing operation—christened “North Pole”—saw them capture two SOE agents in March 1942, one of them a Dutch radio operator named Hubertus Lauwers.

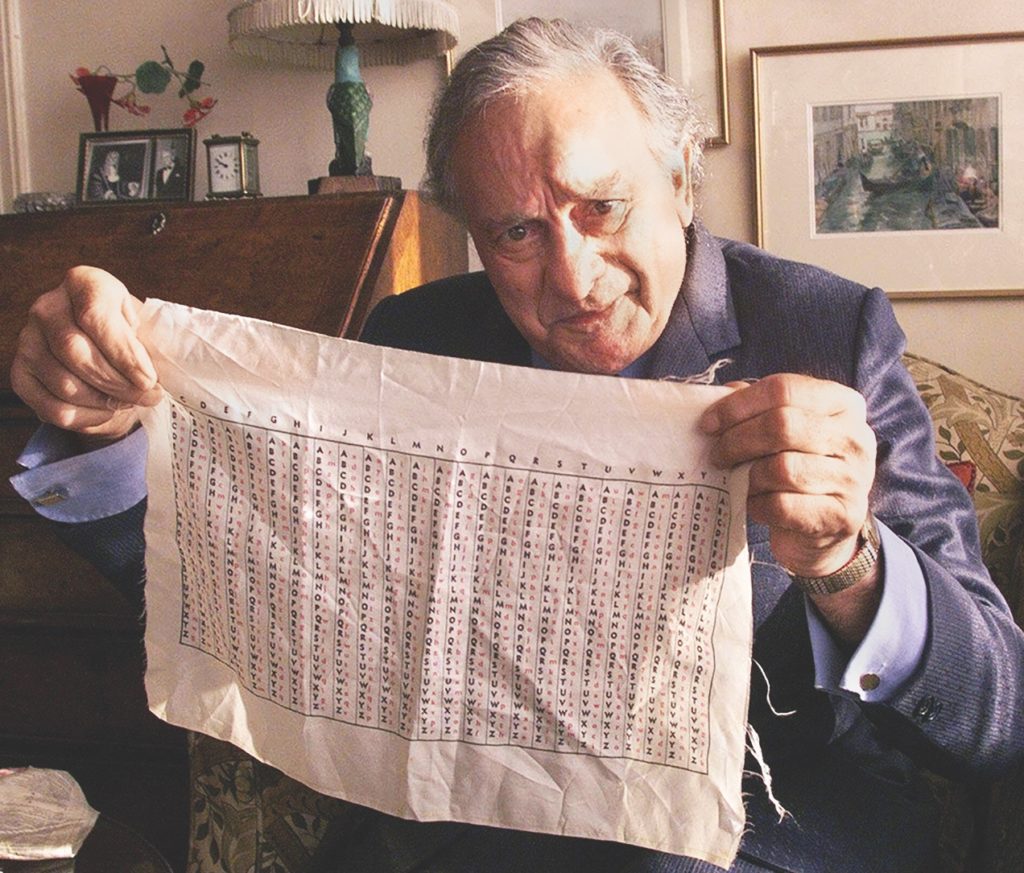

Lauwers, a bespectacled 26-year-old who’d been working on a rubber plantation in Singapore before the war, had been in Holland for four months before then, signaling faithfully and using security checks, as he had been trained. Giskes told Lauwers that he could save his and his fellow agent’s life by acting as if nothing was wrong and transmitting messages to London drafted by the Abwehr. To the Dutchman’s alarm, Giskes asked him what security checks he used, but Lauwers managed to come up with a plausible lie. He went on air confident that SOE would see that the genuine checks were missing and treat his messages with appropriate suspicion.

This, unfortunately, was putting more faith in Lauwers’s British masters than they deserved. His signals, when they came in, were flagged “BLUFF CHECK OMITTED, TRUE CHECK OMITTED”—both security checks missing—but this was ignored. It was one of the things Marks had questioned when he joined SOE a few months later, only to be told not to worry.

Dutch radio operator Hubertus Lauwers repeatedly tried to signal his British handlers that he’d been captured—but all his efforts were in vain. And while the British didn’t notice the warnings, the Germans did, and replaced him. (The National Archives, UK)

That directive wasn’t entirely unjustified: the radio signals at that range were faint, and it was possible that the messages had been mistranscribed. But the main reason Baker Street ignored the red flags was that the controllers chose to. While SOE’s French and Polish sections seemed to have plenty to report, the Dutch section had struggled to recruit agents and get them into the country. It had only three active agents at the start of March 1942. It was preferable to believe they were all safe and starting to get results.

Errors compounded on errors. Eight more agents were sent into Holland in the next two months. One was so badly injured on landing that he took the cyanide pill every agent was supplied with. The Abwehr, working with the Gestapo, picked up the other seven after SOE sent Lauwers—then under German control—a message about how to get in touch with one of them. That left a single SOE agent at large, Georgius Dessing—codename “Carrot.” He went to a rendezvous with one of his colleagues, unaware that the man had already been captured and was accompanied by an undercover Nazi escort. Fortunately the contact managed to whisper the word “Gestapo” to Dessing in time for him to slip away. Dessing had been dropped without a radio operator; the meeting had been his chance to link up with one through SOE colleagues. With no way to contact London, he spent a few more months in Amsterdam, and then decided Holland was too hot and made for Switzerland.

After that, SOE dropped all its agents to what it believed were Dutch resistance reception committees. By the end of 1942 there had been 25 of them, including Ubbink, all arrested on landing.

The agents’ interrogators quickly found that the best way to break them was to tell them they had been betrayed by someone in London. Most believed this—something had, after all, obviously gone badly wrong—and many immediately started talking. Even those who, like Ubbink, tried to hold important details back ended up helping with future interrogations. Trivial facts—the style of mustache worn by a training officer, say, or the color of a door at another site—were still useful in persuading future prisoners that the Germans knew everything there was to know because they had someone on the inside.

It wasn’t just people that Giskes and his crew captured: there was equipment, including new types of communications apparatus, and substantial amounts of money. The Germans also learned the identities of suggested contacts in the Netherlands, leading to round-ups of possible resistance and opposition figures. Trying to take credit for the successful operation, the Gestapo referred to it not by the Abwehr’s “North Pole” designation, but by a new name: “Das Englandspiel”—“The England Game.”

concerns of compromise

HUBERTUS LAUWERS continued sending signals the Abwehr had drafted for him. Giskes had deliberately not replaced him: radio men had distinctive ways of tapping out Morse, and Giskes feared the British would notice if Lauwers were replaced and his style—his “fist”—changed suddenly.

Concerned that SOE apparently hadn’t detected the absence of his security checks, Lauwers tried other ways to warn them. He was supposed to close his messages “QRU”—a common radio term meaning “I have nothing further”—but instead began sending “CAU.” And when he wanted to change frequency, he was supposed to send “QSY,” but instead sent “GHT”—hoping someone in England would realize that he was spelling out “CAUGHT.” Allowed to send random letters at the beginning and end of his messages, he tried to include the phrase “Worked BY JERRY SINCE MARCH SIX”—but the Abwehr, perhaps fearing a move like this, forbade him from using vowels. In any case, London didn’t notice. The only people who spotted Lauwers’s attempts were his captors, who finally replaced him with a German who could imitate his fist. No one in Britain noticed the change.

It was early 1943 when Marks had a sudden insight into the troubling nature of the Dutch signals. Every other section’s agents made mistakes in coding, so why didn’t the Dutch? There was no evidence from their training that they were especially skilled. He began investigating and discovered something else. Alone of SOE’s agents, the Dutch never asked London to repeat a transmission because of interference. It was almost as though the Dutch agents were working with better equipment, and without the stress and fear of being caught that caused others to make mistakes. And the reason for that could be that they had already been caught.

Marks was convinced—but a lack of mistakes was a thin basis for suggesting that an agent was compromised. His bosses were doubtful. Like their colleagues in the Dutch section, they had an incentive to believe everything was fine. They were engaged in a bureaucratic war with Britain’s intelligence agency, the Secret Intelligence Service—known as MI6. MI6 had resented SOE from the start, arguing that the Nazi crackdowns that had followed SOE’s sabotage operations put its own agents at risk. A disaster on the scale Marks was suggesting might see SOE closed down.

And so the SOE’s response to Marks’s warnings was to urge him to say nothing and to do nothing themselves. Meanwhile, agents continued to drop into Holland: eight more in February 1943 and another three in March.

a narrow escape

ONE OF THOSE THREE was Pieter Dourlein, 24, a former policeman and sailor. “When in a normal mood, he is most reasonable, quiet, almost shy,” his SOE trainers reported. “But when angered he seems to lose some of his self control.” It was in such a temper that he had, in 1941, killed a Dutch Nazi, which was the reason he’d fled to Britain, stealing a lifeboat to make the journey. Having lived in Holland under occupation and managed to make his escape, he was a strong recruit for SOE. His codename was “Sprout.”

Dourlein and his team had the same experience as the rest of the agents SOE had dropped into Holland: a friendly greeting—on this occasion with English cigarettes and a nip of whisky—a few questions about who they were supposed to meet next, and then a grab from behind and handcuffs.

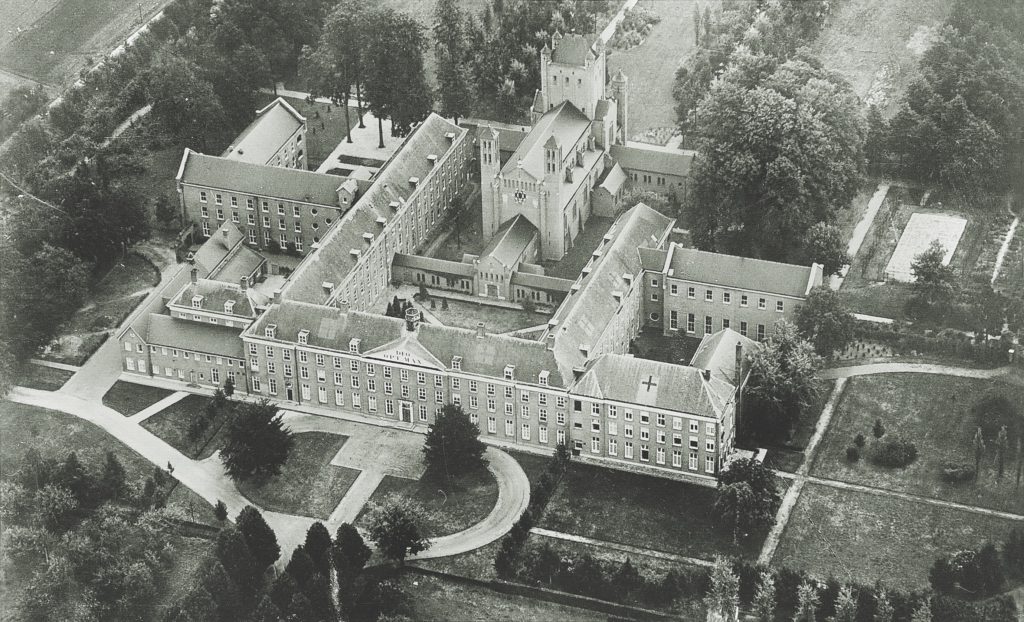

The agents were taken to a converted seminary in Haaren, in the south of the country. Dourlein was disappointed to find that most of his fellow prisoners had little interest in escaping. It seemed impossible and, in any case, a little pointless: SOE was apparently compromised, and their captors were treating them well and had promised they would not be killed so long as they cooperated. He tried to get a message back to SOE via some Dutch civilians in the prison who were in contact with MI6, but his warning became garbled as it was passed from contact to contact, and SOE didn’t know what to make of it when it arrived. This is an insufficient excuse: enough of the message was clear to alert SOE that parachutists, including Dourlein, had been arrested. And MI6 could have helped interpret the rest, had it wanted to. Instead, it delayed passing the warning on for two weeks.

It was the uncooperative approach of another section of the British military that saved SOE from sending still more agents into German hands. In May 1943, the Royal Air Force informed SOE it would no longer make transport runs over Holland. This was Giskes’s fault. He’d gotten into the habit of alerting the Luftwaffe whenever a drop was coming, with the understanding that the British planes would only be attacked on the return trip. The result was that Dutch runs were unusually dangerous for RAF pilots. This, again, should have been a warning to SOE that something was wrong—but it was, again, ignored.

Over in Haaren, Dourlein didn’t believe the Nazi promises that he would be kept alive. The prisoners could communicate with neighboring cells by tapping out Morse on their radiator pipes, and he discovered that Ubbink, in the cell next to him, was also interested in escape. They dug a tiny hole in the wall between them and began to whisper plans.

Above each of their cell doors was a barred window. SOE agents had received briefings on escape techniques before they set off—often from British prisoners of war who had escaped during World War I. One of the tips he remembered was that prison bars were often far enough apart to squeeze through. Using a piece of thread, he measured his, and reckoned he could do it. He and Ubbink cut up their bedsheets to make a rope—both men were sailors and knew their knots—and then waited for their moment. They chose a moonless Sunday at the end of August 1943.

That evening, the pair waited in their cells for the dinner trolley to come round. One of Dourlein’s cellmates begged him to call the escape off—“They’ll only shoot you”—but he was determined to go. Their cell door was flung open, and plates of food shoved in. When Dourlein heard the trolley turn the corner in the corridor outside their cell, he knocked on the wall, the signal to go. He stealthily opened the window above his cell door and stuck his head out between the bars. From the next cell, he could see Ubbink doing the same. It was the first time they had laid eyes on each other. The coast was clear, and they squeezed through the bars and scurried to the end of the corridor, where they knew there was an empty cell.

There, they waited for the dinner trolley to return from its rounds and then crept along behind it to a bathroom used by the guards, where they planned to hide until midnight. For six hours they sat, occasionally speaking in whispers and hoping no guards noticed that one stall was permanently occupied. Outdoors there was a thunderstorm: good weather for a jailbreak.

As midnight approached, they opened the bathroom window. Outside, a guard was plying his searchlight beam along the prison’s windows. They waited until it had passed them before looping their ropes around a bar on the window, squeezing out, and sliding to the ground. They were out of the building, but there was a barbed-wire fence around the compound. On their stomachs they crawled toward it. A patrolling guard passed them without noticing anything. Ubbink scaled the fence first and Dourlein followed, pulling his sleeves over his hands to protect against the sharp barbs. He got caught on them briefly but pulled himself free and dropped to the ground. They were out and sprinting for freedom.

Getting out of the prison was one thing. Getting out of the country was the next challenge. Their clothes were torn and covered in mud. The Germans would soon discover they were missing. They set out to make pursuit as confusing as possible by walking in loops, changing direction and making their way down the middle of ditches before they headed for a nearby town and threw themselves on the mercy of a Catholic priest. Their luck held: the priest passed them to sympathetic locals who hid them and worked out an escape plan. It was a slow, frustrating process, involving weeks of inactivity interrupted by nerve-wracking journeys between hiding places as they traveled through Belgium to Paris and then on south, but in late November 1943 they crossed the border into neutral Switzerland.

They reported immediately to the British military attaché: SOE’s Dutch networks were fatally compromised.

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.

losing the game

BY NOW, THERE WERE serious rumblings on Baker Street that something had gone wrong. MI6—which thanks to its own networks in the Netherlands had suspected problems for some time—had at last passed along a warning. Georgius Dessing had finally made it back to London and reported his experience. Combined with the other indicators, it was all too much to ignore. But there was still a reluctance to face facts. After Dourlein and Ubbink escaped, Hermann Giskes had an alert sent, ostensibly from another SOE agent, that the pair had been captured by the Gestapo and been turned. As a result, some in London clung to the hope that the two agents’ arrival in Switzerland might be part of a Nazi plan to destabilize SOE, and that the rest of the Dutch networks were solid. Even when the pair made it back to London the following year, they were treated with suspicion and kept under guard until after D-Day.

But SOE could no longer avoid the truth. In January 1944, Winston Churchill was told by his chief military assistant, General Hastings Ismay, the “very disquieting” news that his secret army in Holland had “for many months been penetrated.”

Giskes, too, knew that the game was up. He had sensed from December 1943 that SOE’s messages to the agents in his hands had grown more cautious. He decided to go out with a flourish. On April 1, 1944, he transmitted the following unenciphered message to London:

We understand that you have been endeavouring for some time to do business in Holland without our assistance. We regret this the more since we have acted for so long as your sole representatives in this country, to our mutual satisfaction. Nevertheless we can assure you that, should you be thinking of paying us a visit on the Continent on any extensive scale, we shall give your emissaries the same attention as we have hitherto, and a similarly warm welcome. Hoping to see you.

The joke wasn’t seen as very funny in London—but then it wasn’t meant to be. It was intended as a humiliation. It wasn’t just agents that SOE had lost; it had sent 355,500 guilders to Holland—roughly $130,000, or about $2 million in today’s money. But the human cost was far worse. Between November 1941 and May 1943, SOE had sent 53 agents into Holland. Fifty-one were caught by the Nazis. Of those—despite the promises that they would be protected—47 were killed, almost all by the SS.

Leo Marks took little pleasure in having been proved right, and decades later still fizzed with anger at the waste of brave lives. After the war he became a playwright and screenwriter—although his most lasting contribution to cinema may have come in the movie Carve Her Name with Pride, about SOE agent Violet Szabo, which featured a 1943 poem by Marks, “The Life That I Have,” that she used to encode her messages.

SOE’s failure in Holland was so total that for decades suspicion lingered in the Netherlands that it must have been deliberate, part of an elaborate deception operation. Surely, the argument went, the wizards of British intelligence couldn’t have been so comprehensively fooled. They must have been playing a double game. The destruction of many of the outfit’s records in a fire in London shortly after the war only stoked those rumors.

But files released since 1998 tell a simpler, sadder tale—of the fog of war, of wishful thinking, and of a refusal to see the truth until it was far too late.