Standing on the waterfront in Portsmouth, with the choppy waters of the harbor sparkling like crumpled aluminum foil in front of me, it’s difficult to make sense of the scathing comments of previous visitors about the English seaside city. American novelist Henry James once labeled Portsmouth “dirty” and “dull.” Jane Austen claimed “its vile sea breezes” were “the ruin of beauty and health.” Current British prime minister Boris Johnson famously quipped it was “full of drugs, obesity, and underachievement.”

Yet while Portsmouth might lack the dreaming spires of Oxford or the cosmopolitan buzz of London, the city has played an epoch-defining role in global history. Its fabled dockyard was once home to the world’s greatest naval port. Here, in the 18th and 19th centuries, intrepid explorers and admirals sallied forth from the heavily fortified waterfront on their way to the empire’s distant shores. But Portsmouth’s biggest test came in 1944, when it took center stage as the operational nexus and launchpad for D-Day, the largest seaborne invasion in history.

In preparation for the landings, top Allied commanders, including Generals Dwight D. Eisenhower and Bernard L. Montgomery, converted Portsmouth into their military headquarters. Pieces of Mulberry Harbors—portable piers later towed across the English Channel and reassembled in France—were secretly built at nearby Hayling Island and, starting on June 6 and continuing through the summer of 1944, over 170,000 troops and an estimated 43,000 tanks and military vehicles embarked for Normandy from the city’s wharves and quays.

Not coincidentally, World War II history is the reason I’m here today. Returning to my native UK from Canada for the first time since the COVID-19 pandemic began, I’m keen to reconnect with the sights and sounds of the region I once called home. I grew up near Portsmouth in a small town in northwest Hampshire in the 1980s. My father—who passed away in the early weeks of the pandemic, aged 95—joined the Royal Air Force the day after D-Day. While he didn’t play any direct part in the Normandy landings, he and his generation were indelibly shaped by the tumultuous events of Operation Overlord and its aftermath. By visiting Portsmouth, I hope to get a better picture of what living through those uncertain times was really like.

It’s sunny and warm as I thread my way through the redeveloped shops and restaurants of Gunwharf Quays in a city craving for normalcy after the ravages of the pandemic. The strict lockdowns of 2020-21 weren’t Portsmouth’s first containment. In 1943, during secret preparations for D-Day, the British military declared the city’s seafront a restricted zone. Rules were tightened in April 1944 when a 10-mile strip running along England’s entire south coast was closed off to visitors. For several months, civilians outside the zone couldn’t enter, while those on the inside were forbidden from leaving.

By this point, Portsmouth had already endured numerous air raids. The city was hit over 60 times between 1940 and 1944 by German bombers, destroying approximately 10 percent of homes and killing nearly 1,000 people. Like many postwar British cities, the landscape that re-emerged in the 1950s and ’60s was haphazard and not always pretty.

Recent building projects—many of them new to my eyes—have been more inspiring. The sail-shaped Spinnaker Tower, a 558-foot-tall observation spire on the harborfront, could have been shipped over from ultramodern Dubai. The Anglican cathedral, extended in the 1990s, is an encouraging example of how to successfully brighten up a dark 12th-century church without wrecking its historic integrity. I pay a brief visit to the cathedral’s hushed interior to admire the D-Day memorial window installed in 1956 that depicts action scenes from Dunkirk and Normandy in vivid stained glass. Backlit by the morning sun, it reflects bright kaleidoscopic patterns onto the surrounding walls and pillars.

Ten minutes later, while navigating my way along the coast toward the grassy expanses of Southsea Common, I stumble upon the Royal Garrison Church, Portsmouth’s most poignant monument to the Blitz. During a 1941 firebombing raid, the building suffered extensive damage, losing the roof of its nave. The roof was never replaced, but the adjacent chancel survived intact and today displays stained glass from the 1980s honoring wartime troops from the Royal Artillery and British Eighth Army.

Almost every town and village in the United Kingdom has a war memorial, but I’ve rarely seen one as magnificent as the one in Portsmouth. Drawing me like a guiding beacon across Southsea Common as I head south, I fixate on its tall classical obelisk guarded by four lions and enclosed by low walls inscribed with the names of around 15,000 naval seamen lost at sea in World War II. Bookended by two barrel-shaped pavilions and fronted by a well-manicured lawn, it looks grand without being ostentatious. Aside from myself, the only other visitors are two murmuring ladies who stroll sedately past the endless names, searching perhaps for an uncle, a father, or a grandfather.

Beyond the memorial lies Portsmouth’s biggest lure, the D-Day Story, the only museum in the UK dedicated to the Normandy landings. Inaugurated in 1984 but significantly upgraded in 2018, the museum’s most conspicuous sight—a giant landing craft called LCT 7074—was parked permanently outside the unassuming redbricked façade in August 2020. The vessel, which successfully delivered nine tanks to Gold Beach during Operation Overlord, is the last surviving landing craft from D-Day. After the war it enjoyed a less illustrious second career as a floating nightclub in Liverpool before being rescued and restored.

Inside, the museum is split into three sections—“Preparation,” “Battle,” and “Legacy.” Newsreel images, dramatic photos, and audio of soldiers who fought on the frontlines add emotion and individual testimony to the invasion’s well-known facts. As a modern-day observer, I find it impossible not to be moved by these men’s palpable sense of fear mixed with bravery and heroism.

The surprise exhibit comes in the “Legacy” section, which is composed almost entirely of the Overlord Embroidery, a 272-foot-long hand-stitched cloth that illustrates the events of D-Day in perfect detail. With its vivid pictorial storytelling, it draws obvious comparison with the Bayeux Tapestry, the 950-year-old embroidered cloth across the Channel in France made to commemorate Norman king William the Conqueror’s invasion of Britain in 1066 (D-Day in reverse). The question is: will the D-Day embroidery still be around in 950 years’ time for 31st-century visitors to peruse?

After tea and scones in the museum cafe and a quick reconnaissance of Southsea’s seafront, anchored by the South Parade Pier from where dozens of ships set sail in 1944, I backtrack to the dockyard and hop on a four-minute ferry ride to Gosport.

Located on the other side of Portsmouth harbor, Gosport is the former home of HMS Dolphin, a Royal Navy submarine base and shore establishment decommissioned in 1999. Several information boards along the waterside esplanade recall its wartime function. However, the real reason I’ve come here is to visit its sprawling Royal Navy Submarine Museum and digest the story of the X-Craft, D-Day’s forgotten heroes.

X-Craft were midget submarines with five-men crews designed in the early 1940s to infiltrate enemy ports, lay explosives, and chart coastlines undetected by the Germans. In January 1944, the midget sub X-20 got close enough to Omaha Beach to dispatch divers who secretly swam ashore and collected sand samples in—no kidding—condoms.

Four days before D-Day, X-20—along with another sub, X-23—left Hayling Island to act as advance guides for the impending armada. For 96 hours, the crews endured dangerous and cramped conditions to reconnoiter the Normandy coast and lay guiding beacons. At one point, one of the subs got so close to Sword Beach the crew spied German troops playing an impromptu game of soccer through the periscope.

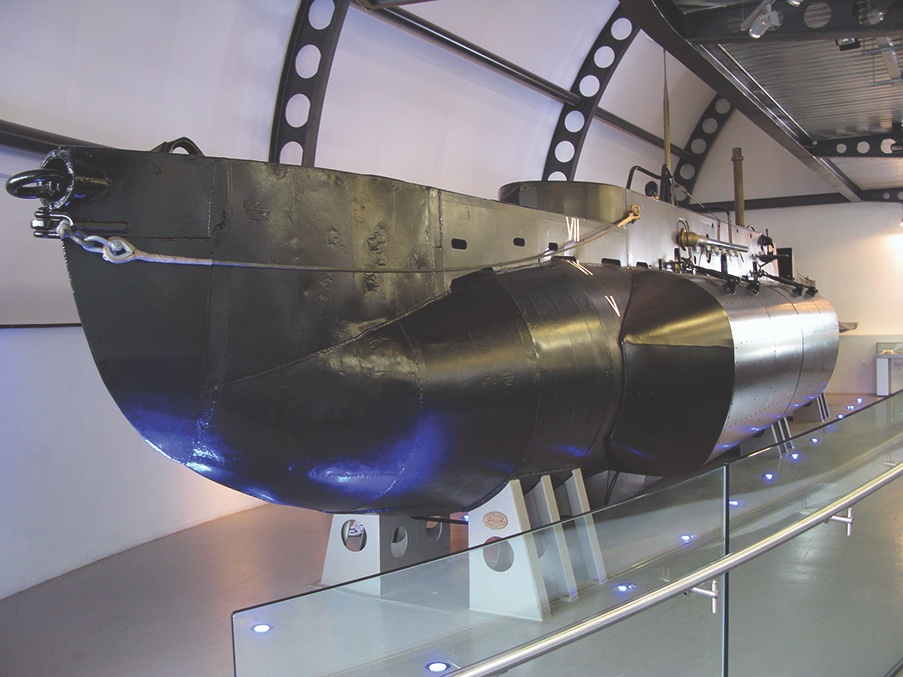

While X-20 and X-23 were scrapped after the war, one X-Craft has survived. Hidden in the museum’s entrails is X-24, a sub that saw active wartime service along the coast of Norway in 1944. Sticking my head momentarily inside its 52-square-foot interior is enough to induce a mild wave of claustrophobia.

Back on Portsmouth’s harborfront, as the late summer sun illuminates a handsome line of taverns that somehow managed to survive the wartime bombs, I take a last look at the cranes, masts, and ferries of this great maritime city and nurture a new appreciation for its wartime heroics. While the battle for France might have been fought on the beaches of Normandy, victory would never have been possible without the steely, behind-the-scenes efforts of my father’s generation and their role in planning D-Day from Britain’s south coast. ✯

WHEN YOU GO

Portsmouth Harbour station is an easy 90-minute journey from London on South Western Railway. The D-Day Story museum and Royal Navy Submarine Museum—across the harbor in Gosport—are both open daily.

Where to Stay and Eat

The Duke of Buckingham offers inn-style accommodations a short walk from Gunwharf Quays. Rooms are small but cozy. The hotel also sports a traditional English pub. Abarbistro, located close to the cathedral, serves interesting small fish plates and Sunday roast dinners.

The Sally Port Inn in Old Portsmouth is a historic pub with connections to World War II frogman and bomb disposal expert Lionel “Buster” Crabb, the supposed model for James Bond.

What Else to See and Do

Along with an X-Craft, the Royal Navy Submarine Museum is home to HMS Alliance, a decommissioned A-class sub laid down at the end of World War II. Also worth a visit is Portsmouth’s historic dockyard, where you can see the remains of King Henry VIII’s warship, the Mary Rose, and climb aboard HMS Victory, the flagship of British admiral Horatio Nelson. The aptly named Victory was crucial in defeating a combined French and Spanish fleet in the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805 during the Napoleonic Wars. ✯