ON JUNE 6, 1944, THE UNITED STATES, BRITAIN, AND CANADA launched the largest force of warships in history across the English Channel. It escorted the largest concentration of troop transport vessels ever assembled, covered by the largest force of fighter and bomber aircraft ever brought together, preceded by a fleet of air transports that had carried tens of thousands of paratroopers and glider-borne troops to Normandy.

Not one German submarine, not one small boat, not one airplane, not one radar set, not one German anywhere detected this movement. As General Walter Warlimont, deputy head of operations of the German Supreme Headquarters, later confessed, on the eve of Overlord, the Wehrmacht leaders “had not the slightest idea that the decisive event of the war was upon them.”

IN WORLD WAR I, SURPRISE ON A GRAND SCALE WAS SELDOM ATTEMPTED and rarely achieved. In World War II, it was always sought and sometimes achieved—as with the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor and the German invasion of Russia, both in 1941, and the German attack in the Ardennes in 1940 and again in 1944. One reason for this difference between the wars was that World War II commanders judged surprise to be more critical to victory than a pre-attack artillery bombardment. In the age of machine guns, other rapid-fire artillery, and land mines, the defenders could make almost any position virtually impregnable, no matter how heavy the pre-attack bombardment. Another reason for the increased emphasis on surprise was that the much greater mobility of World War II armed forces made surprise more feasible and more effective. Because of improvements in and more imaginative use of the internal-combustion engine (especially in tanks and trucks), the geographic area in which the conflict fought was much larger in World War II. The pre-invasion bombardment for Overlord, carried out by aircraft, was spread all across France and Belgium. It may have wasted a lot of bombs, but it also kept the Germans from discerning a pattern that would indicate the invasion site.

Recommended for you

None of the surprises achieved in World War II was more complex, more difficult, more important, or more successful than Overlord. To fool Hitler and his generals in the battle of wits that preceded the attack, the Allies had to convince them not only that it was coming where it was not, but also that the real thing was a feint. The first objective could be achieved by attacking in an unexpected, indeed illogical, place, and by maintaining total security about the plan. The second required convincing Hitler that the Allied invasion force was about twice as powerful as it actually was.

allies relied on surprise

That there would be landings in France in the late spring of 1944 was universally known. Exactly where and when were the questions. To learn those secrets, the Germans maintained a huge intelligence organization that included spies inside Britain, air reconnaissance, monitoring of the British press and BBC, radio intercept stations, decoding experts, interrogation of Allied airmen shot down in Germany, research on Allied economies, and more.

The importance of surprise was obvious. In World War I, it was judged that to have any chance at success, the attacking force had to outnumber the defenders by at least three to one. But in Overlord, the attacking force of 175,000 men would he outnumbered by the Wehrmacht, even at the point of attack, and the overall figures (German troops in Western Europe versus Allied troops in the United Kingdom) showed a two-to-one German advantage. Doctrine in the German army was to meet an attack with an immediate counterattack.

In this case, the Germans could move reinforcements to the battle much faster than the Allies, because they could bring them in by train, by truck, and on foot, while the Allies had to bring them in by ship. The Germans had storage and supply dumps all over France; the Allies had to bring every shell, every bullet, every drop of gasoline, every bandage across the Channel.

Allied intelligence worked up precise tables on the Germans’ ability to move reinforcements into the battle area. The conclusion was that if the Germans correctly gauged Overlord as the main assault and marched immediately, within a month they could concentrate 31 divisions in the battle area, including nine panzer divisions. The Allies could not match that buildup rate.

In the face of these obstacles, the Allies managed to maintain a deception about their true intentions even after the battle began. How they did so is a remarkable story.

the art of the double-cross

Thousands of men and women were involved, but perhaps the most important, and certainly the most dramatic, were the dozen or so members of BI(a), the counterespionage arm of MI-5, the British internal-security agency. Using a variety of sources, such as code breaking and interrogation of captured agents, the British caught German spies as they parachuted into England or Scotland. Sir John Masterman, head of BI(a), evaluated each spy. Those he considered unsuitable were executed or imprisoned. The others were “turned”—that is, made into double agents, who sent messages to German intelligence, the Abwehr, via radio, using Morse code. (Each spy had his own distinctive “signature” in the way he used the code’s dots and dashes, which was immediately recognizable by the German spy master receiving the message.) The British kept the double agents tap-tap-tapping, but only what they were told to send out.

This so-called Double-Cross operation, which had come into being in the dark days of 1940, managed to locate and turn every German spy in the United Kingdom, some two dozen in all. From the beginning the British had decided to aim it exclusively toward the moment when the Allies returned to France. Building up this asset over the years required feeding the Abwehr information through the spies that was authentic, new, and interesting, but either relatively valueless or something the Germans were bound to learn anyway. The idea was to make the agents trustworthy and valuable in the eyes of the Germans, then spring the trap on D-Day, when the double agents would flood the Abwehr with false information.

The first part of the trap was to make the Germans think the attack was coming at the Pas de Calais. Since the Germans already anticipated that this was where the Allies would come ashore, it was necessary only to reinforce their preconceptions. The Pas de Calais was indeed the obvious choice. It was on the direct London—Ruhr—Berlin line. It was close to Antwerp, Europe’s best port. Inland the terrain was flat, with few natural obstacles. At the Pas de Calais the Channel was at its narrowest, giving ships the shortest trip and British-based fighter aircraft much more time over the invasion area.

Because the Pas de Calais was the obvious choice, the Germans had their strongest fixed defenses there, backed up by the Fifteenth Army and a majority of the panzer divisions in France. Whether or not they succeeded in making the position impregnable we will never know, because the supreme Allied commander, Dwight D. Eisenhower, decided not to find out. He chose Normandy instead. Normandy had certain advantages, including the port of Cherbourg, the narrowness of the Cotentin Peninsula, access to the major road network at Caen, and proximity to the English ports of Southampton and Portsmouth. Normandy’s greatest advantage, however, was that the Germans were certain to consider an attack there highly unlikely, because it would be an attack in the wrong direction: Instead of heading east, toward the German heartland, the Allies would be heading south into central France.

The second part of the trap was to make the Germans think, even after the attack began, that Normandy was a feint. Geography reinforced Eisenhower’s choice of Normandy in meeting this requirement, too: If there were major Allied landings at the Pas de Calais, Hitler would not keep troops in Normandy for fear of their being cut off from Germany—but he might be persuaded to keep troops in the Pas de Calais following a landing in Normandy, as they would still stand between the Allied forces and Germany.

The deception plan, code-named Fortitude, was a joint venture, with British and American teams working together; it made full use of the Double-Cross system, dummy armies, fake radio traffic, and elaborate security precautions. In terms of the time, resources, and energy devoted to it, Fortitude was a tremendous undertaking. It had many elements, designed to make the Germans think the attack might come at the Biscay coast or in the Marseilles region or even in the Balkans. Most important were Fortitude North, which set up Norway as a target (the site of Hitler’s U-boat bases, essential to his offensive operations), and Fortitude South, with the Pas de Calais as the target.

To get the Germans to look toward Norway, the Allies first had to convince them that Eisenhower had enough resources for a diversion or secondary attack. This was doubly difficult because of Ike’s acute shortage of landing craft—it was touch and go as to whether there would be enough craft to carry five divisions ashore at Normandy as planned, much less spares for another attack. To make the Germans believe otherwise, the Allies had to create fictitious divisions and landing craft on a grand scale. This was done chiefly with the Double-Cross system and through Allied radio signals.

The British Fourth Army, for example, stationed in Scotland and scheduled to invade Norway in mid-July, existed only on the airwaves. Early in 1944 some two dozen overage British officers were sent to northernmost Scotland, where they spent the next months exchanging radio messages. They filled the air with an exact duplicate of the wireless traffic that accompanies the assembly of a real army, communicating in low-level and thus easily broken cipher. Together the messages created an impression of corps and division headquarters scattered all across Scotland: “80 Div. request 1,800 pairs of crampons, 1,800 pairs of ski bindings,” they read, or “7 Corps requests the promised demonstrators in the Bilgeri method of climbing rock faces.” There was no 80th Division, no VII Corps.

The turned German spies meanwhile sent encoded radio messages to Hamburg and Berlin describing heavy train traffic in Scotland, new division patches seen on the streets of Edinburgh, and rumors among the troops about going to Norway. Wooden twin-engine “bombers” began to appear on Scottish airfields. British commandos made some raids on the coast of Norway, pinpointing radar sites, picking up soil samples (ostensibly to test the suitability of beaches to support a landing), and in general trying to look like a pre-invasion force.

hitler fortifies norway

The payoff was spectacular. By late spring, Hitler had 13 army divisions in Norway (about 130,000 men under the German military system) along with 90,000 naval and 60,000 Luftwaffe personnel. In late May, Field Marshal Erwin Rommel finally persuaded Hitler to move five infantry divisions from Norway to France. They had started to load up and move out when the Abwehr passed on to Hitler another set of “intercepted” messages about the threat to Norway. He canceled the movement order.

To paraphrase Winston Churchill, never in the history of warfare have so many been immobilized by so few.

Fortitude South was larger and more elaborate. It was based on the First U.S. Army Group (FUSAG), stationed in and around Dover and threatening the Pas de Calais. It included radio traffic; inadequately camouflaged dummy landing craft in the ports of Ramsgate, Dover, and Hastings; fields packed with paper-maché tanks; and full use of the Double-Cross setup. The spies reported intense activity in and around Dover, including construction, troop movements, increased train traffic, and the like. They said that the phony oil dock at Dover, built by stagehands from Hollywood and the British film industry, was open and operating.

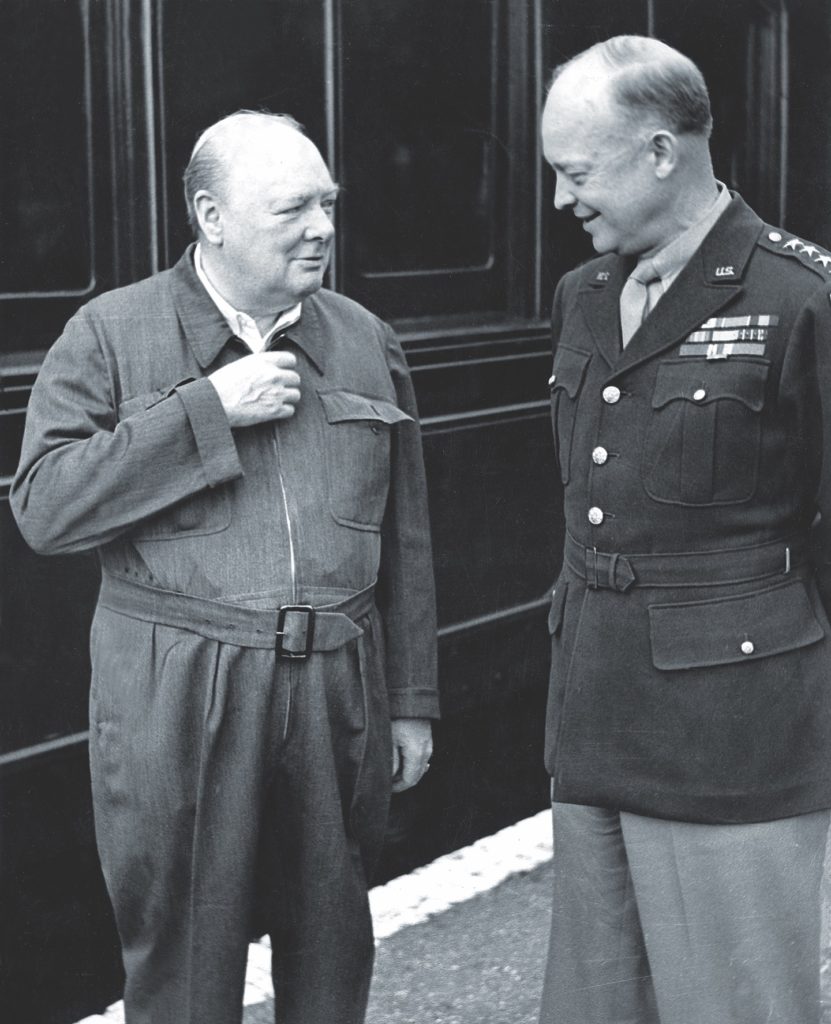

The capstone to Fortitude South was Ike’s selection of General George S. Patton to command FUSAG. The Germans thought Patton the best commander in the Allied camp (a judgment with which Patton hilly agreed, but which Eisenhower, unbeknownst to the Germans, did not) and expected him to lead the assault. Eisenhower, who was saving Patton for the exploitation phase of the campaign, used Patton’s reputation and visibility to strengthen Fortitude South. The spies reported his arrival in England and his movements. FUSAG radio signals told the Germans of Patton’s comings and goings and showed that he had taken a firm grip on his new command.

FUSAG contained real as well as notional divisions, corps, and armies. The FUSAG order of battle included the U.S. Third Army, which was real but still in the United States; the British Fourth Army, which was imaginary; and the Canadian First Army, which was real and based in England. There were, in addition, supposedly fifty follow-up divisions in the United States, organized as the U.S. Fourteenth Army—which was notional—awaiting shipment to the Pas de Calais after FUSAG established its beachhead. Many of the divisions in the Fourteenth Army were real and were actually assigned to General Omar Bradley’s U.S. First Army in southwest England.

Fortitude’s success was measured by the German estimate of Allied strength. By June 1, the Germans believed that Eisenhower’s entire command included 89 divisions (of about 15,000 men each), when in fact he had 47. They also thought he had sufficient landing craft to bring 20 divisions ashore in the first wave, when he would be lucky to manage five. Partly because they credited Ike with so much strength, and partly because it made such good military sense, the Germans believed that the real invasion would be preceded or followed by diversionary attacks and feints.

ike presses churchill

SECURITY FOR OVERLORD WAS AS IMPORTANT AS DECEPTION. As Ike declared, “Success or failure of coming operations depends upon whether the enemy can obtain advance information of an accurate nature.” To maintain security, in February he asked Churchill to move all civilians out of southernmost England. He feared there might be an undiscovered spy who could report the truth to the Abwehr. Churchill refused; he felt it was too much to ask of a war-weary population. A British officer on Ike’s staff said it was all politics, and growled, “If we fail, there won’t be any more politics.”

Ike sent Churchill an eloquent plea, warning that it “would go hard with our consciences if we were to feel, in later years, that by neglecting any security precaution we had compromised the success of these vital operations.” In late March, Churchill gave in; the civilians were put out of all coastal and training areas and kept out until months after D-Day.

Eisenhower also persuaded a reluctant Churchill to impose a ban on privileged diplomatic communications from the United Kingdom. Ike said he regarded diplomatic pouches as “the gravest risk to the security of our operations and to the lives of our sailors, soldiers, and airmen.” When Churchill imposed the ban, on April 17 , foreign governments protested vigorously. This gave Hitler a useful clue to the timing of Overlord. He remarked in early May that “the English have taken measures that they can sustain for only six to eight weeks.” When a West Point classmate of Ike’s declared at the bar in Claridge’s Hotel that D-Day would be before June 15, and offered to take bets when challenged, Ike reduced him in rank and sent him home in disgrace. There was another flap a week later when a U.S. Navy officer got drunk and revealed details of impending operations, including areas, strength, and dates. Ike wrote Chief of Staff George C. Marshall, “I get so angry at the occurrence of such needless and additional hazards that I could cheerfully shoot the offender myself.” Instead, Ike sent the officer back to the States.

TO CHECK ON HOW WELL SECURITY AND DECEPTION WERE WORKING, SHAEF (Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force) had another asset, the Ultra system. This involved breaking the German code, Enigma, enabling SHAEF to read German radio signals. Thanks to Ultra, the British Joint Intelligence Committee was able to put together weekly summaries of “German Appreciation of Allied Intentions in the West,” one- or two-page overviews of where, when, and in what strength the Germans expected the attack. Week after week, the summaries gave Ike exactly the news he wanted to read: that the Germans were anticipating an attack on Norway, diversions in the south of France and in Normandy or the Bay of Biscay, and the main assault, with twenty or more divisions, against the Pas de Calais.

But Fortitude was an edifice built so delicately, precisely, and intricately that the removal of just one supporting column would bring the whole thing crashing down. On May 29, with D-Day only about a week away, the summary included a chilling sentence: “The recent trend of movement of German land forces towards the Cherbourg area tends to support the view that the Le Havre—Cherbourg area is regarded as a likely, and perhaps even the main, point of assault.”

Had there been a slip? Had the Germans somehow penetrated Fortitude?

The news got worse. The Germans, in fact, were increasing their defenses everywhere along the French coast. In mid-May, the mighty Panzer Lehr Division began moving toward the Cotentin Peninsula, while the 21st Panzer Division, which had been with Rommel in North Africa and was his favorite, moved from Brittany to the Caen area—exactly the site where the British Second Army would be landing. More alarming, Ultra revealed that the German 91st Division, specialists in fighting paratroopers, and the German 6th Parachute Regiment had moved on May 29 into exactly the areas where the American airborne divisions were to land. And the German 352nd Division moved forward from Saint-Lo to the coast, taking up a position overlooking Omaha Beach, where the U.S. 1st Division was going to land.

Ike’s air commander, British Air Chief Marshal Sir Trafford Leigh-Mallory, was so upset by this news that he recommended to Ike that the airdrops be canceled. Ike refused, but the German movements and Leigh-Mallory’s reaction badly stretched his nerves.

Garbo gives the word

Eisenhower did not, however, give up on Fortitude. At about midnight on June 5—6, even as Allied transport planes and ships began crossing the Channel for Normandy, the supreme commander played the ultimate note in the Fortitude concert: He had the spy the Germans trusted most, code-named Garbo—actually a resourceful spy for the British from the start—send a message in Morse code to the Abwehr giving away the secret. Garbo reported that Overlord was on the way, named some of the divisions involved, indicated when they had left Portsmouth, and predicted they would come ashore in Normandy at dawn.

The report had to be deciphered, read, evaluated, re-ciphered, and transmitted to Hitler. Then Hitler’s lackeys had to decide whether to wake him with the news. They did, but then the whole encoding and deciphering operation had to be reversed to get the word to the German forces in Normandy. By the time it arrived, the defenders could see for themselves—there were 6,000 planes overhead and 5,000 ships off the coast, and the first wave of troops was coming ashore.

In short, Garbo’s report, the most accurate and important of the entire war, arrived too late to help the Germans. But it surely raised their opinion of Garbo—and this was vital. For now that Fortitude had helped the Allies get ashore, the question was, could the deception be kept alive long enough to let the Allies win the battle of the buildup that would follow?

Garbo was the key. On June 9 he sent a message to his spy master in Hamburg with a request that it be submitted urgently to the German high command. “The present operation, though a large-scale assault, is diversionary in character,” Garbo stated flatly. “Its object is to establish a strong bridgehead in order to draw the maximum of our [German] reserves into the area of the assault and to retain them there so as to leave another area exposed where the enemy could then attack with some prospect of success.” Citing the Allied order of battle as the Germans understood it, Garbo pointed out that Eisenhower had committed only a small number of his divisions and landing craft. He added that no FUSAG unit had taken part in the Normandy attack, nor was Patton there. Furthermore, “the constant aerial bombardment which the sector of the Pas de Calais has been undergoing and the disposition of the enemy forces would indicate the imminence of the assault in this region which offers the shortest route to the final objective of the Anglo-Americans, Berlin.”

Within half a day, Garbo’s message was in Hitler’s hands. On the basis of it, the führer made a momentous decision, possibly the most important of the war. Rommel had persuaded Hitler to send two Fifteenth Army panzer divisions to Normandy. The tanks had started their engines, the men were ready to go, when Hitler canceled the order. He wanted the armored units held in the Pas de Calais to defend against the main invasion. He also awarded the Iron Cross (second class) to Garbo. (Garbo, a young Spaniard whom the British, secretly, also honored, ended a long silence about his elaborate and risky activities only in 1985, with the book Operation Garbo.)

The deception went on. On June 13, another spy warned that an attack would take place in two or three days at Dieppe or Abbeville. A third spy reported that airborne divisions (wholly fictitious) would soon drop around Amiens. In late June a fourth agent, code-named Tate, said he had obtained the railway schedule for moving the FUSAG forces from their concentration areas to the embarkation ports, thus reinforcing from a new angle the imminence of the threat to the Pas de Calais. One Abwehr officer considered Tate’s report so important that he said it “could even decide the outcome of the war.” He was not far wrong.

The weekly intelligence summary on June 19 read: “The Germans still believe the Allies capable of launching another amphibious operation. The Pas de Calais remains the expected area of attack. Fears of landings in Norway have been maintained.”

July 10: “The enemy’s fear of large-scale landings between the Seine and the Pas de Calais has not diminished. The second half of July is given as the probable time for this operation.”

July 24: “There has been no considerable transfer of German forces from the Pas de Calais, which remains strongly garrisoned.”

By August 3, when Patton came onto the Continent with his U.S. Third Army, most German officers realized that Normandy was the real thing. By then, of course, it was too late. The Germans had kept hundreds of their best tanks and thousands of their finest fighting men (a total of 15 divisions in France) out of this crucial battle in order to meet a threat that had always been imaginary.

german conceits exploited

THERE WERE DELICIOUS IRONIES AT THE HEART OF FORTITUDE’S SUCCESS. Surprise in war often depends on the defenders underestimating the strength of the attacking force, but in Overlord that was reversed: Fortitude made the Germans overestimate Eisenhower’s strength. Surprise also usually depends on exploiting the defenders’ weaknesses, but this, too, got turned around: As in jujitsu, Eisenhower employed German strength to German disadvantage.

The Germans in 1944 held three major conceits as articles of faith. The first was that their spies in the United Kingdom were the best in the world. The second was that their Enigma was the best encoding machine ever developed, literally unbreakable. The third was that their own code breakers were the best available. Fortitude used these German conceits to do the Germans in.

Twenty-two years after the event, in 1966, when the author was interviewing Eisenhower on the subject of Fortitude, the supreme commander explained various parts of the operation, then gave one of his big, gutsy laughs, slapped his knee, and exclaimed, “By God, we really fooled them, didn’t we?”

STEPHEN E. AMBROSE, was a professor of history at the University of New Orleans. He is the author of several books on military history and was a frequent contributor to MHQ.

This article originally appeared in the Summer 1989 issue (Vol. 1, No. 4) of MHQ—The Quarterly Journal of Military History.