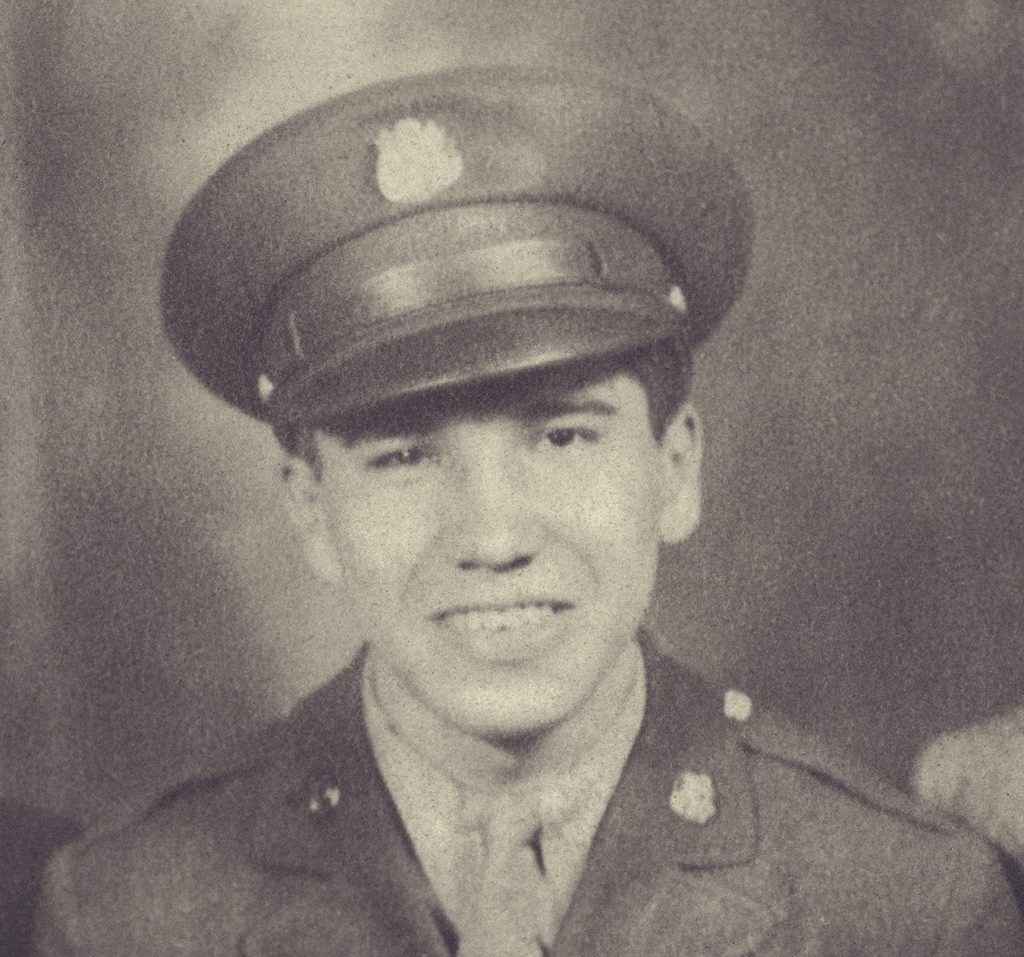

BORN IN 1924 in Bristol, Connecticut, Charles Norman Shay is a tribal elder with the Penobscot Nation and grew up on the reservation on Indian Island, Maine. Drafted as a medic into the 16th Infantry Regiment, 1st Infantry Division, in 1943, Shay’s introduction to combat came when he landed in the first wave at Omaha Beach on June 6, 1944. He was awarded a Silver Star for his courage that day in rescuing wounded men from drowning and went on to see action at the Battle of Hürtgen Forest and the Battle of the Bulge. He remained in the military after the war; served with distinction in Korea, earning three Bronze Stars; and has spent decades living in Europe. Since 2018 Shay, now 97, has made Normandy his home, living 20 miles from Omaha Beach. At 6:30 a.m. each June 6 he performs a traditional Penobscot ceremony by the sea to honor his comrades who never returned home.

You were born in 1924—the year Congress enacted the Indian Citizenship Act, which granted citizenship to all Native Americans born in the United States.

Yet the right to vote was governed by state law—and Maine refused to give us that right [until 1954]. My mother was an activist who campaigned throughout her life for more rights for Native Americans; this was one of the things she was fighting for. She had four sons, but she did not think they should serve in the U.S. military if they could not vote.

But you and your brothers all served.

Yes. I was the only one of the four to serve in the army. I was drafted in Boston and sent to Camp Pickett, Virginia, for basic training. Once I got into military service, the White men knew that I was a Native American and accepted me as such. I was told at that time that I was going to be a medic. I did not choose myself; they told me what I was going to do.

How did you come to join the 1st Infantry Division—the Big Red One?

I arrived in England in November 1943, and I was sent to Bridport [on the south coast], where the 1st Infantry Division’s 16th Regiment was stationed. I was selected to be a combat medic with the regiment’s F Company, 2nd Battalion.

You participated in Operation Tiger in April 1944, when German E-boats attacked a D-Day rehearsal in the English Channel, killing 750 Americans.

I was there, but my ship was not involved with what happened that day. We were all told not to talk about it or discuss it with anybody. The U.S. military did not want the American public to know about it.

Were you apprehensive that your nerve might falter when under fire for the first time?

No: I was told what my job was. I was thereto treat the wounded and do what I could do to save them. This kept my mind occupied. I had no fear. I knew I could do my job because I had been trained for it.

How was the weather on the voyage across the Channel?

Very bad. The landing craft were on the side of our troopship, the USS Henrico, and they were going up and down with the waves. Crewmen threw rope ladders over the side, and we had to crawl down. The men who had made it into the craft gave advice to those coming afterward, telling us when to jump because there was the danger that if you landed at the wrong time you’d break your legs, or you could miss the landing craft and be drowned or crushed to death.

What was it like exiting the landing craft at Omaha Beach?

The Germans had put up underwater obstacles in the sea. The coxswain in charge of our landing craft announced over his intercom system: “Prepare to disembark because I am marooned on an underwater obstacle, and I cannot move.” He dropped the ramp, and of course we were under constant machine gun, rifle, artillery, and mortar fire. Of the men standing at the front of the craft when the ramp went down, many were hit immediately, and some were killed. Others were overloaded, and when they jumped into the sea they drowned because they were weighed down with machine guns, bazookas, and ammunition.

As a medic I had only my two satchels and a life vest. When I left the landing craft I landed in water about up to my chest. I made my way to the obstacles the Germans had put up. I was using these for protection. Most of the men who had landed were doing the same thing. I was able to make a dash for the beach, got there, and started treating the wounded.

One of whom was your best friend.

Yes: another medic, Private Edward Morozewicz. He received a stomach wound and had a large opening in his abdomen. It was a wound I could not treat. I knew he was dying, and he knew he was dying. I stayed with him and tried to console him and prepare him for his departure into the future world. While I was talking with him, he died.

Were you surprised at your composure given your age and inexperience?

Yes, because I had never been in such situations before. I was able to treat the wounded and see men die. I don’t know how I was able to do it, but I was.

How did you cope with all the wounded?

I was not concerned with the degree of the wound; I just did all I could. Some of the men, of course, there was no help for them, but I treated them anyway and bandaged their wounds. Perhaps later they died, but I did not stay around.

Describe the action for which you were awarded a Silver Star.

When I landed, I found an area far up the beach where the seas had come up over a couple of hundred years and washed up all this debris. I selected that spot to treat the wounded because it was protected. I happened to glance back out to the sea and saw there were many wounded men lying near the shore. The tide was coming in very fast. I dropped what I was doing and ran to help them. Many of the wounded were much bigger than I was, so I rolled them onto their backs so they could breathe; I reached under the arms of the others and pulled them to the high-water mark and left them there. I did this until I became exhausted and had to take a break. Then I continued.

Did you come to the attention of the Germans?

This man in bunker WN 62 [Heinrich Severloh, who claimed to have killed hundreds of Americans from his perch overlooking Omaha Beach]—he saw me. He started shooting and I could see the bullets hitting the sand around my feet, but he did not hit me.

How did the rest of D-Day pan out?

In treating the wounded, I became separated from my company. So I attached myself to the 26th Infantry Regiment [which had landed at 7:30 p.m.] and followed them inland toward Colleville-sur-Mer. I was completely exhausted, laid down behind a bush, and went to sleep. When I woke, it was very early in the morning. I looked around where I was sleeping and there was nothing but dead Americans and Germans.

Did you find your company?

Yes—but my company had taken heavy casualties and was not a combat unit anymore. We had to stay and get replacements so we could be an effective unit again.

You faced another blow at the Battle of Hürtgen Forest in fall 1944.

I lost another friend there: an artillery shell exploded in the top of a tree and shrapnel showered down and hit him. He called for me. I saw that he was seriously wounded and was going to die. Back at the command post, I broke down. I started crying and could not stop. I was sent to the battalion medical aid station to recuperate. A few days later I returned to F Company.

How did your war end?

I was captured in March 1945 near the German village of Auel not long after I’d crossed the river Sieg—a tributary of the Rhine—as part of a reconnaissance squad. I was held in Stalag VI-G, close to Bonn. The Germans treated us good. They knew they had lost the war, and I was liberated in April.

Have you watched Saving Private Ryan?

No. I never watched any of those type of films. My parents invited me to the movies one evening not long after I’d come home [in the summer of 1945]. The news came up and the first item was about the war. I got up and walked out. It continues to this day. But I read a lot of books, particularly about the 1st Infantry Division.

You came through the war without a scratch, as you did the Korean War. Were you born under a lucky star?

I could never understand why I was never wounded either from shrapnel or machine gun fire. I have always said that I survived only through my mother’s prayers. ✯

This article was published in the February 2022 issue of World War II.