That 1942 was the turning point of World War II is one of those “facts” that everyone knows. Like much of the received wisdom on the war, however, the concept of its “turning point” requires a certain amount of nuance. This conflict, more than any other before it, was a vast and sprawling set of interlocking campaigns on land, sea, and air. It involved hundreds of millions of human beings, from the freezing cold of the Arctic to the sweltering heat of the Burmese jungle, and the notion that there was a single discrete moment that “turned” it is problematic, to say the least.

Still, it is clear that something important happened in 1942. It was, after all, the year of El Alamein in the African theater, and of Midway and Guadalcanal in the Pacific. To paraphrase Winston Churchill, before 1942 the Allies never won a victory, and after 1942 they never suffered a defeat. But for that year to live up to its billing as the “hinge of fate,” in Churchill’s memorable phrase, a fatal blow had to be dealt to the German armed forces, the Wehrmacht. Could the Allies, even with their sheer superiority in materiel and men, pull it off?

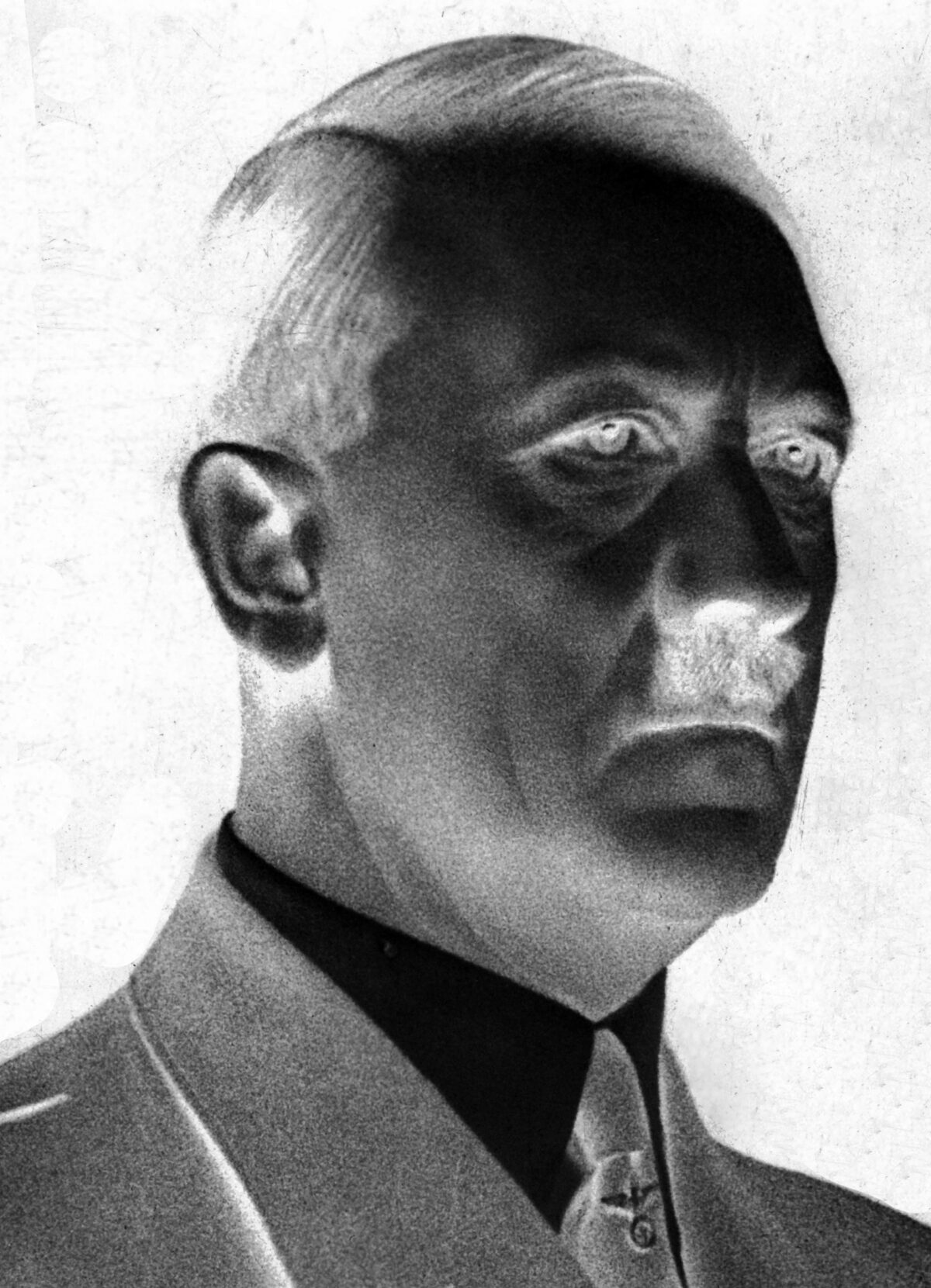

The Reich had been locked in a conflict with Great Britain since September 1939, one that it tried half-heartedly to end in the summer and fall of 1940. Since mid-1941, it had done nothing but add enemies. On June 22, with Britain still unconquered, the German führer, Adolf Hitler, had launched an invasion of the Soviet Union, Operation Barbarossa. In its early weeks, the Wehrmacht had smashed one Soviet army after another: at Bialystok, at Minsk, at Smolensk, and especially at Kiev. As summer turned to fall, Barbarossa evolved into Operation Typhoon, a drive on Moscow. The Germans were within sight of the Soviet capital by December 6, when the Red Army launched a great counteroffensive that drove them back in confusion, inflicting punishing losses on an army that had been largely untouched by the first two years of the war. The very next day, the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor, and five days later Hitler declared war on the United States.

Earlier in the year, Germany had been at war with Britain alone. Six short months later, it was at war with an immense and wealthy enemy coalition, which Churchill, with a nod to his great ancestor the Duke of Marlborough, dubbed the “Grand Alliance.” The alliance controlled the vast majority of the world’s resources. It included the preeminent naval and colonial power (Britain), the largest land power (the Soviet Union), and the globe’s financial and industrial giant (the United States): more than enough potential power to smash Germany. But Germany’s situation, being ringed and vastly outnumbered by an alliance of powerful enemies, was nothing particularly new in Prusso-German military history.

In fact, the Reich’s next, and what was to be its last, major campaign—drives to capture Stalingrad and the oil fields of the Caucasus—seemed to offer another textbook opportunity for the Germans to demonstrate that sound maneuver tactics and strategy grounded in more than a century of experience—and including the modern mechanized variant, blitzkrieg—could best even the massive forces arrayed against them.

Until the war’s end, on the eastern front and elsewhere, Germany sought to land a resounding blow against one of its enemies, one hard enough to shatter the enemy coalition, or at least to demonstrate the high price that the Allies would have to pay for victory. The strategy certainly did its share of damage in those last four years, and the Allies and most historians play down how frighteningly close it came to succeeding.

While the German strategy for winning the war failed—and did so spectacularly in 1942—no one at the time or since has been able to come up with a better solution to Germany’s strategic conundrum. Was it a war-winning gambit? Not in this case, obviously. Was it the best strategy under the circumstances? Perhaps, perhaps not. Was it an operational posture in complete continuity with German military history and tradition as it had unfolded over the centuries? Absolutely.

In 1942 the Wehrmacht provided a characteristic answer to the question, “What do you do when the Blitzkrieg fails?” It launched another— indeed, a whole series of them. The centerpiece of 1942 would be another grand offensive in the east. Operation Blue (Unternehmen Blau) objectives would include a lunge over the mighty Don River to the Volga, the seizure of the great industrial city of Stalingrad, and, finally, a wheel south into the Soviet Caucasus, home to some of the world’s richest oil fields. With the final Operation Blue objectives more than a thousand miles from the start line, no one can accuse Hitler and the high command of thinking small.

Yet what might have seemed a reach for another country’s army appeared achievable by the Wehrmacht, steeped as it was in a winner-takes-all tradition. Since the earliest days of the German state, a unique military culture had evolved, one that we can call a “Ger man way of war.” Its birthplace was the kingdom of Prussia. Starting in the 17th century with Friedrich Wilhelm, the Great Elector, Prussia’s rulers recognized that their small, impoverished state on the European periphery had to fight wars that were kurz und vives (short and lively). Crammed into a tight spot in the middle of Europe, surrounded by states that vastly outweighed it in both manpower and resources, Prussia could not win long, drawn-out wars of attrition. Instead, it had to fight short, sharp wars that ended in rapid, decisive battlefield victories. Its conflicts had to be front-loaded, unleashing a storm against the enemy, pounding him fast and hard, and making him see reason as soon as possible.

This solution to Prussia’s strategic problem was something the Germans called Bewegungskrieg— the war of movement. It was a way of war that stressed maneuver on the operational level. It was not simply tactical maneuverability or a faster march rate but the rapid movement of large units—divisions, corps, and armies. Prussian commanders sought to maneuver their formations in such a way that they could strike the mass of the enemy army a sharp, even annihilating, blow as rapidly as possible. It might involve a surprise assault against an unprotected flank, or against both flanks. On several notable occasions, as in the Great Elector’s winter campaign against the Swedes in 1678–79 and Field Marshal Helmuth von Moltke’s signal triumph over the French at Sedan in 1870, it even resulted in entire Prussian or German armies getting into their enemy’s rear, the dream scenario of any general.

The desired end was something called the Kesselschlacht: literally, a “cauldron battle,” but more specifically a battle of encirclement, one that hemmed in the enemy on all sides before destroying him through a series of “concentric operations.” This vibrant operational posture imposed certain requirements on German armies: an extremely high level of battlefield aggression and an officer corps that tended to launch attacks no matter what the odds, to give just two examples.

The Germans also found over the years that conducting an operational-level war of movement required a flexible system of command, one that left a great deal of initiative in the hands of lower-ranking commanders. It is customary today to refer to this command system as Auftragstaktik (mission tactics): the higher commander devised a general mission (Auftrag) and then left the means of achieving it to the officer on the spot. It is more accurate, however, to speak, as the Germans themselves did, of the “independence of the lower commander” (Selbständigkeit der Unterführer). A commander’s ability to size up a situation and act on his own was an equalizer for a numerically weaker army, allowing it to grasp opportunities that might be lost if it had to wait for reports and orders to climb up and down the chain of command.

While this way of war had served Germany well up to 1941, it had clearly come up short during Operation Barbarossa, and it would be easy to view Operation Blue as doomed from the start. The near-collapse of the previous winter had left scars that had not yet healed, and there is for the connoisseur a smorgasbord of unhappy statistics from which to choose.

For some, it might be the 1,073,066 casualties that the Wehrmacht suffered in its first nine months in the Soviet Union. For others, it might be the General Staff’s estimated replacement deficit of 280,000 men by October 1942, a minimum figure that was valid only if things went well and operations succeeded with relatively light casualties. The one hundred seventy-nine thousand horses lost in the Soviet Union in the first year were not going to be replaced anytime soon, and the loss figures for motor transport were equally dismal. An Oberkommando des Heeres (OKH) report in May found the figure at only 85 percent of the trucks required for the army’s mobile divisions of the spearhead. A report from the Army Organization Section warned that it was closer to 80 percent and those at the sharp end thought the situation was a great deal worse.

Gen. Walter Warlimont, deputy chief of operations for the high command (Oberkommando der Wehrmacht, or OKW), warned that the army’s mobility was going to be “considerably affected,” adding that “a measure of demotorization” was inevitable—dire words indeed for an army that lived and died by operational-level maneuver. Although historians often speak of the Germans scraping the bottom of the manpower barrel in 1944–45, they had already started that process in 1942. The class of 1923 had already been drafted in April 1941, eighteen months ahead of time, and raw 18- and 19-year-old recruits would play a key role in filling out the rosters of the new divisions being formed for Blue.

Perhaps the best indicator of Germany’s new military economy of scarcity is this: of the forty-one new divisions slated for Case Blue, fully twenty-one of them would be non-German: ten Hungarian, six Italian, and five Romanian. It was a sure sign that the Germans were having difficulty with the enormity of the front, which by now stretched some seventeen hundred miles from Murmansk in the north to Taganrog in the south.

There were other problems. The German emphasis on maneuver usually meant they devoted less time and effort to vital areas like logistics and intelligence. Like so many great German military operations, this one would be based on an abysmally inaccurate portrait of enemy strength. The Germans estimated available Soviet aircraft at 6,600 planes; the reality was 21,681; they estimated they were facing 6,000 tanks; the actual number was 24,446; the German estimate of Soviet artillery (7,800 guns) was also off by a factor of four (the actual number was 33,111). All in all, the intelligence failure of 1942 was one of the worst in German history, rivaled only by the failure of these same agencies during the run-up to Operation Barbarossa.

Yet this campaign did not appear to be at all hopeless to Hitler, to Josef Stalin, or to their respective staffs. Indeed, the preliminaries to Blue showed that the Wehrmacht still brought to the table some formidable operational skills: May 1942 saw Field Marshal Erich von Manstein’s decisive victory at Kerch in the Crimea, an equally impressive win at Kharkov in the Ukraine, and finally Gen. Erwin Rommel’s decisive victory over the British at Gazala in the Western Desert. Kerch, Kharkov, and Gazala were all classic examples of the “war of movement,” operational-level battles of annihilation marked by high mobility, a freewheeling and aggressive officer corps, and successful attempts to surround and destroy the enemy.

Rommel would punctuate his victory by storming Tobruk in June, invading Egypt, and driving for Suez; that same month, Manstein placed an exclamation point on his Crimean campaign by taking the great fortress of Sevastopol. In the course of these five big wins, the Wehrmacht smashed every enemy army it met and took six hundred thousand prisoners; its own losses were almost nonexistent aside from Sevastopol, which had been a bloody affair. For all its manpower and equipment shortages, it is hard to disagree with historian Alan Clark when he described 1942 as “the Wehrmacht at high tide.”

Nor did the opening of Operation Blue disappoint. The Red Army had also been seriously blooded in the past year’s fighting, and its initial response to Blue was nothing less than a full speed, helter-skelter retreat. It seems to have been ordered by Stalin and Gen. Georgi K. Zhukov as a classic maneuver to trade space for time, traditional in Russian wars. On the lower levels, however, it was carried out ineptly, with huge stretches of territory abandoned without a fight, a great deal of equipment lost, and a conspicuous absence of command and control.

For the last time in this war, it was full steam ahead for the Wehrmacht. The Germans and their Hungarian allies rapidly closed up to the Don River, with Fourth Panzer Army (Colonel General Hermann Hoth) seizing the great city of Voronezh in the north on day ten of the offensive, and then wheeling south toward the Don bend, skirting the river on its left. To Hoth’s right, Sixth Army (Field Marshal Friedrich Paulus) crossed the starting line against sporadic Soviet opposition, lunged fifty miles ahead within the first forty-eight hours, and linked up with Fourth Panzer at Stary Oskol. No wonder Hitler actually looked at his situation map at the time and exulted that “the Russian is finished.”

Even as Hitler was speaking these happy words, however, the operational wheels were falling off of Blue. The initial operational plan (Directive 41) had called for a very complex set of maneuvers designed to produce small but airtight encirclements quite close to the start line. Such clearly defined plans were necessary, Hitler felt, in order to give the young soldiers in his army an early taste of victory. He and his chief of the general staff, Colonel General Franz Halder, were also anxious to avoid the kind of operational chaos that had manifested itself during the drive on Moscow in 1941, when it seemed as if every German commander was fighting his own private war. Modern historians have a love affair with Auftragstaktik, but clearly it has its dangers, and both Hitler and Halder were determined to run a tighter ship this time.

Unfortunately for them, the Soviet retreat, chaos and all, had knocked the air out of this idea from the start. The outcome of one army tethered to the tight plans of its high command and the other fleeing from the scene was a pair of what the Germans called Luftstossen—blows into the air—great German pincer movements that closed on nothing much in particular. It happened at Millerovo on July 15, and then again at Rostov on July 23. The amount of ground covered had been impressive; Hoth’s Fourth Panzer Army, in particular, had driven from Voronezh all the way down to Rostov in a single month. In the end, however, the Wehrmacht had achieved little beyond eating through its already limited pile of supplies.

Hitler’s response turned this puzzling misfire into an absolute catastrophe. “Directive 45” was a fundamental reworking of Operation Blue. The original timetable had called for smashing all the Soviet armies in the Don bend, taking Stalingrad as a northern flank guard for the army’s drive into the Caucasus, and only then launching the drive into the oil fields. Now, less than a month into the operation, Hitler ordered the Wehrmacht to secure Stalingrad and the Caucasus at the same time. Historians usually identify this decision to launch a “dual offensive” as the great blunder of the campaign, with an army already running low on manpower and equipment trying to do everything at once, and it is hard to argue with the common wisdom.

The problems were evident early. The German drive into the Caucasus (Operation Edelweiss) received priority in terms of supply and transport, and was thus able to explode out of the box, lunging forward hundreds of miles and seizing one of the USSR’s three great oil cities, Maikop; but the drive on Stalingrad (Operation Fischreiher, or “Heron”) was a tough grind from the start. This imbalance led, within a week, to another reversal of priorities. Stalingrad was now the primary target. Edelweiss lost supply, air cover, and an entire panzer army, with Hoth motoring north to join Paulus. The entire Caucasus campaign was left in the hands of just two Ger – man armies, First Panzer on the left and Seventeenth on the right, with the Romanian Third Army holding the extreme right wing.

This was the moment that both halves of the dual campaign— the drive east to Stalingrad and the drive south to the Caucasus— came to a screeching halt. In German parlance, the freewheeling war of movement (Bewegungskrieg) suddenly turned into the static war of position (Stellungskrieg), just the sort of grinding attritional struggle that the Wehrmacht knew it could not win.

In the south, the Germans got stuck on the approaches to the high mountains, their two armies facing a solid wall of eight Soviet armies comprising the Transcaucasus Front (further divided into a “Black Sea Group” and a “North Group” of four armies apiece). In the north, Sixth Army reached Stalingrad at the end of September, its arrival punctuated by a Luftwaffe raid on the city that reduced much of it to rubble; Fourth Panzer Army joined it on September 2, and the Luftwaffe announced the coming of Hoth by smashing the city a second time, churning up a great deal of rubble, killing thousands more civilians, and nearly bagging the Soviet commander in Stalingrad, General Vasili I. Chuikov of the Sixty-second Army.

The two German armies had met and reestablished a continuous front directly in front of Stalingrad. Now was a time for decisions. In front of the Germans lay a great city, with a population of some six hundred thousand and a large heavy-industry base. Just a few months earlier, the Wehrmacht had suffered some seventy-five thousand casualties reducing the much smaller city of Sevastopol, the bloodiest encounter of the spring by a considerable margin. Stalingrad, moreover, presented an unusual set of geographical problems. Rather than a collection of neighborhoods radiating out of some central point, the city was one long urbanized area stretching along the right bank of the Volga for nearly thirty miles, as straight as a railroad tie.

In operational terms, therefore, it was not so much a city as a long, fortified bridgehead on the western bank of the river. The Germans could never put it under siege. Behind it flowed a great river, behind the river a huge mass of artillery that could intervene in the battle at will, and behind the artillery a vast, secure, and rapidly industrializing Soviet hinterland.

Not for the first time in this war, the Wehrmacht had conquered its way into an impasse. It could not go forward without sinking into a morass of urban fighting. Every German officer knew what a city fight would mean. The preferred way of war, Bewegungskrieg, would inevitably degenerate into Stellungskrieg. Indeed, Hitler and the General Staff had designed the entire convoluted operational sequence in 1942 for the very purpose of avoiding this prospect. At the same time, however, it could not simply go around Stalingrad, and there was no possibility of staying put, not with Paulus and Hoth both sitting out on the end of a very long and vulnerable limb.

Given a choice of three unpalatable alternatives, the Ger man army made the only decision consonant with its history and traditions, dating back to Frederick the Great, Field Marshal Gebhard Leberecht von Blücher, and Moltke. On September 5, the big guns roared, the panzers stormed forward, and the Stukas screamed overhead. The assault on Stalingrad had begun.

Every student of the war knows what happened next—how the fighting broke down into battles for the crumbling buildings and rubble-strewn streets of the dying city. Both sides incurred huge losses. The Germans, as usual, kept attacking, driving ever closer to the Volga riverbank that was their operational objective. Their last shot (Operation Hubertus, in November) would take them just a few hundred yards away from it. The Soviets were managing to hold on, just barely, to an ever-narrowing strip along the river.

In operational terms, the “dual offensive” was now firmly stuck in neutral, and this at a moment when Rommel, too, had come to a dead stop in the desert. His own last shot—the offensive at Alam Halfa, August 30 to September 7—had also broken down against a revived British Eighth Army. The Wehrmacht was in deep trouble, shorn of its own ability to maneuver and seemingly helpless against enemy strength that was waxing on all fronts.

And yet, modern war—and the peculiar Ger- man variant of it, Bewegungskrieg, remained unpredictable. Even in extremis, with a balance of forces that had gone bad and a logistical situation that edged ever closer to disaster, the Wehrmacht could still show occasional flashes of the old fire. Take the Caucasus. As the summer turned into fall, with the Black Sea front frozen in place, the focus of the campaign shifted to the east, along the Terek. The last of the major rivers in the region, it was deep and swiftly flowing, with steep, rocky banks that sheltered a number of key targets: the cities of Grozny and Ordzhoni kidze (modern Vladi kavkaz), as well as the Ossetian and Georgian military roads. These roads were the only two routes through the mountains capable of bearing motor traffic, and taking them would give the Wehrmacht effective control of the Caucasus. The Georgian Road was the key. Running from Ordzhoni kidze down to Tbilisi, it would give the Germans the potential for a high-speed drive through the mountains to the Caspian Sea and the rich oil fields around Baku, the greatest potential prize of the entire campaign.

By October, First Panzer Army had concentrated what was left of its fighting strength along the Terek. Col. Gen. Eberhard von Mackensen’s III Panzer Corps was on the right, LII Corps in the center, and XXXX Panzer Corps on the left, at Mozdok. On October 25, Mackensen’s corps staged the last great set-piece assault of the Caucasus campaign, aiming for an envelopment of the Soviet Thirty-seventh Army near Nalchik. Mackensen had the Romanian 2nd Mountain Division on his right, and much of his corps’ muscle (13th and 23rd Panzer Divisions) on his left. The Romanians would lead off and punch a hole in the Soviet defenses, fixing the Thirty-seventh Army’s attention to its front. The next day, two panzer divisions would blast into the Soviet right, encircling the defenders and ripping open a hole in the front. Once that was done, the entire corps would wheel to the left (east), heading toward Ordzhonikidze.

It went off like clockwork. The Romanians opened the attack on October 25th, along with a German battalion (the 1st of the 99th Alpenjäger Regiment). Together they smashed into Soviet forces along the Baksan River and penetrated the front of the Thirty-seventh Army, driving toward Nalchik across three swiftly flowing rivers, the Baksan, Chegem, and Urvan.

Ju 87 Stukas supported the attack, achieving one of the war’s great victories by destroying the Thirty-seventh Army’s headquarters near Nalchik, a blow that left the Soviet army leaderless in the first few crucial hours of the attack.

The next evening, the two panzer divisions attacked by moonlight, crossing the Terek and achieving complete surprise. Soon they had blocked the roads out of Nalchik, and the Wehrmacht had achieved one of its few Kesselschlachts in the entire Caucasus campaign. Some survivors of the Thirty-seventh Army limped back toward Ordzhonikidze; others apparently threw off discipline and fled to the mountains directly to the south.

Now the Panzer divisions wheeled left, heading due east, with the mountains forming a wall directly on their right. With 23rd Panzer on the right and 13th on the left, it was an operational spearhead reminiscent of the glory days of 1941. On October 27 and 28, the panzers crossed one river after the other, the Lesken, the Urukh, the Chikola, with the Soviets either unwilling or unable to form a cohesive defense in front of them. By October 29, they had reached the Ardon River, at the head of the Ossetian Military Road; on November 1, the 23rd Panzer Division took Alagir, closing the Ossetian road and offering the Wehrmacht the possibility of access to the southwestern Caucasus through Kutais to Batum. At the same time, the 13th Panzer Division was driving toward the corps’ main objectives: Ordzhonikidze and the Georgian Military Road.

Kleist now ordered the division to take the city on the run. That evening, 13th Panzer’s advance guard was less than ten miles from Ordzhonikidze. It had been through some tough fighting, and just the day before, its commander (Lt. Gen. Traugott Herr) had suffered a severe head wound. Under a new commander, Lt. Gen. Helmut von der Chevallerie, it ground forward over the next week against increasingly stiff Soviet opposition; indeed, so heavy was Soviet fire that the new general had to use a tank to reach his new command post.

On November 2, 13th Panzer took Gizel, just five miles away from Ordzhonikidze. The defenders, elements of the Thirty-seventh Army, heavily reinforced with a Guards rifle corps, two tank brigades, and five antitank regiments, knew what was at stake here and were stalwart in the defense. Mackensen rode his panzer divisions like a jockey, first deploying the 23rd Panzer Division on the right of the 13th, then shifting it to the left, constantly looking for an opening. Closer and closer to Ordzhonikidze they came. There was severe resistance every step of the way, with the 13th Panzer Division’s supply roads under direct fire from Soviet artillery positions in the mountains, heavy losses in the rear as well as the front.

The image of two punch-drunk fighters is one of the oldest clichés in military history, but perfectly de- scribes what was happening. It was a question of re- serves, physical and mental: Who would better stand the strain in one of the century’s great mano a mano engagements? It had it all: bitter cold, swirling snowstorms, and a majestic wall of mountains and glaciers standing watch in the background. The road network failed both sides, so columns had to crowd onto branch roads where they were easy prey for enemy fighter-bombers. Rarely have Stukas and Sturmoviks had a more productive set of targets, and the losses on both sides were terrible.

By November 3, the 13th Panzer Division had fought its way over the highlands and was a mere two kilometers from Ordzhonikidze. By now, a handful of battalions was carrying the fight to the enemy, bearing the entire weight of the German campaign in the Caucasus. For the record, they were the 2nd of the 66th Regiment (II/66th) on the left, II/93rd on the right, with I/66th echeloned to the left rear. Deployed behind the assault elements were the I/99th Alpenjäger, the 203rd Assault Gun Battalion, and the 627th Engineer Battalion. The engineers’ mission was crucial: to rush forward and open the Georgian Military Road the moment Ordzhonikidze fell.

Over the next few days, German gains were measured in hundreds of meters: six hundred on November 4, a few hundred more on November 5. By now, it had become a battle of bunker-busting, with the German assault formations having to chew their way through dense lines of fortifications, bunkers, and pillboxes. Progress was slow, excruciatingly so, but then again the attackers didn’t have all that far to go. Overhead the Luftwaffe thundered, waves of aircraft wreaking havoc on the Soviet front line and rear, and pounding the city itself. Mackensen’s reserves were spent, used up a week earlier, in fact. It must have been inconceivable to him that the Soviets were not suffering as badly or worse.

But Mackensen was wrong. On November 6, the Soviets launched a counterattack, their first real concentrated blow of the entire Terek campaign, against the 13th Panzer’s overextended spearhead. Mixed groups of infantry and T-34 tanks easily smashed through the paper-thin German flank guards and began to close in behind the mass of the division itself, in the process scattering much of its transport and cutting off its combat elements from their supply lines. Supporting attacks against the German left tied up the 23rd Panzer Division and the Romanian 2nd Mountain Division just long enough to keep them from coming to 13th Panzer’s assistance. There were no German reserves, and for the next three days, heavy snowstorms kept the Luftwaffe on the ground. Indeed, the 13th Panzer only had the strength for one last blow—to the west, as it turned out—to break out of the threatened encirclement. After some shifting of units, including the deployment of the 5th SS-Panzer Division Wiking in support, the order went out on November 9. The first convoy out of the pocket used tanks to punch a hole, followed by a convoy of trucks filled with the wounded. Within two days, a badly mauled 13th Panzer was back on the German side of the lines. The drive on Ordzhonikidze had failed, as had the drive on the oil fields of Grozny, and, indeed, the Caucasus campaign itself.

But how close it had been! Consider the numbers. Take a German army group of five armies and reduce it to three, and then to two. Give it an absurd assignment, say a 700-mile drive at the end of a 1,200-mile supply chain, against a force of eight enemy armies, in the worst terrain in the world. Wear down its divisions to less than 50 percent of their strength, both in men and tanks. Then make it 33 percent. Feed them a hot meal perhaps once a week. Remove them from the control of their professional officer corps and put them into the hands of a lone amateur strategist. Throw them into sub-zero temperatures and two feet of snow.

Add it all up, and what do you get? Not, surprisingly, an inevitable defeat, but a hard-driving panzer corps, stopped but still churning its legs, less than two kilometers from its strategic objective. Karl von Clausewitz was right about one thing: war is, indeed, “the realm of uncertainty.”

Dramatically, in May 1942 the Wehrmacht began the campaigning season with some of the greatest operational victories in the entire history of German arms: Kerch, Kharkov, and Gazala. All of them took place within weeks of one another. Then, in the summer, the Wehrmacht brought down the curtain on this very successful season with the reduction of Tobruk and Sevastopol. After providing all the participants with enough terrifying moments to last several lifetimes, the year’s fighting ended improbably but with equal drama just six months later, with the Germans suffering two of the most decisive reversals of all time: El Alamein and Stalingrad.

Again, these two signal events took place within weeks of one another. Field Marshal Erwin Rommel’s Panzerarmee Afrika was still streaming across North Africa in some disarray—ignoring Hitler’s last-second order to stand fast—at the very moment that the Soviets were launching Operation Uranus, which encircled the German Sixth Army in Stalingrad.

In those brief six months, an entire way of war that dated back centuries had come to an end. The German tradition of maneuver-based Bewegungskrieg, the notion that “war is an art, a free and creative activity,” the belief in the independence of the subordinate commander: each of these bedrock beliefs had taken a pounding in the past six months, and in fact had revealed themselves as no longer valid. The war of movement as practiced by the German army had failed in the wide-open spaces of the Soviet Union; the southern front especially presented challenges that it was not designed to handle.

The notion of war as an art was difficult to maintain in the face of what had happened in North Africa and on the Volga. Here, enemy armies looked on calmly as the Wehrmacht went through its ornate repertoire of maneuver, then smashed it with overwhelming materiel superiority: hordes of tanks, skies filled with aircraft, seventy artillery gun tubes per kilometer. German defeat in both theaters looked far less like an art than an exercise in a butcher’s shop: helpless raw materials being torn to shreds in a meat grinder.

The German pattern of making war, grounded in handiwork and tradition and old-world craftsmanship, had met a new pattern, one that had emerged from a matrix of industrial mass production and boundless confidence in technology. At El Alamein and Stalingrad, the German way of war found itself trapped in the grip of the machine.

Another aspect of Bewegungskrieg, independent command, also died in 1942. The new communications technology, an essential ingredient in the Wehrmacht’s earlier victories, now showed its dark side. Radio gave the high command a precise, real-time picture of even the most rapid and far-flung operations. It also allowed staff and political leaders alike to intervene in the most detailed and, from the perspective of field commanders, the most obnoxious way possible. The new face of German command, 1942-style, was evident in the absurd Haltbefehl to Rommel in the desert and the incessant debates between Hitler and Field Marshal Wilhelm List about how to seize the relatively minor Black Sea port of Tuapse.

At the height of the battle of Zorndorf in 1758, Frederick the Great ordered his cavalry commander, Friedrich Wilhelm von Seydlitz, to launch an immediate counterstroke on the left of the hard-pressed Prussian infantry. When it seemed late in coming, the king sent a messenger to Seydlitz with orders to march immediately, and with threats if he did not do so.

Seydlitz, however, was a commander who only moved when he judged the moment ripe. His response was part of the mental lexicon of every Ger man commander in the field in 1942: “Tell the king that after the battle my head is at his disposal,” he told the king’s messenger, “but meantime, I hope he will permit me to exercise it in his service.”

Those days were evidently long gone by 1942. Hitler symbolically took a number of heads in this campaign while the fight was still raging: Bock, List, Halder, and many others were retired. The new dispensation was most evident in the attenuated struggle within the Stalingrad Kessel. Paulus may have been cut off from supply, but he certainly wasn’t cut off from communication. From Hitler’s first intervention (his orders of November 22 that “Sixth Army will hedgehog itself and await further orders”) to the last (the January 24 refusal of permission to surrender), the Führer had been the de facto commander of the Stalingrad pocket.

This is not to exculpate Paulus’s pedestrian leadership before the disaster and his curious mixture of fatalism and submission to the Führer once he had been encircled. Indeed, Paulus may have welcomed Hitler’s interventions as a way of evading his own responsibility for the disaster. But Hitler did not kill the concept of flexible command. Radio did.

Like any deep-rooted historical phenomenon, Bewegungskrieg died hard. It resisted both the foibles of Hitler’s personality and the more complex systemic factors working against it. Those haunting arrows on the situation maps will remain fixed permanently to our historical consciousness as a reminder of what a near-run thing it was: the 13th Panzer Division, operating under a brand new commander, just a mile outside Ordzhonikidze and still driving forward; German pioneers in Operation Hubertus, bristling with flamethrowers and satchel charges, blasting one Soviet defensive position after another and driving grimly for the Volga riverbank just a few hundred yards away; Rommel’s right wing at Alam Halfa, a mere half-hour’s ride by armored car from Alexandria. Rarely have the advance guards of a subsequently defeated army ever come so tantalizingly close to their strategic objectives.

In the end, the most shocking aspect of 1942 is how absurdly close the Wehrmacht came to taking not one but all of its objectives for 1942: splitting the British Empire in two at Suez and paving the way for a drive into the Middle East, while seizing the Soviet Union’s principal oil fields, its most productive farmland, and a major share of its industries.

Originally published in the Autumn 2008 issue of Military History Quarterly. To subscribe, click here.