At around noon on May 2, 1972, two SR-71 Blackbirds dropped to 75,000 feet and flew separate Mach 2.5 passes over Hanoi, delivering two sonic booms within 15 seconds of each other. Their mission was vital and their timing critical. A third SR-71 had orbited offshore as a spare in case something forced one of the others to abort. The planes’ pilots and crew didn’t know the mission’s purpose, but executed it perfectly. The mission was repeated two days later.

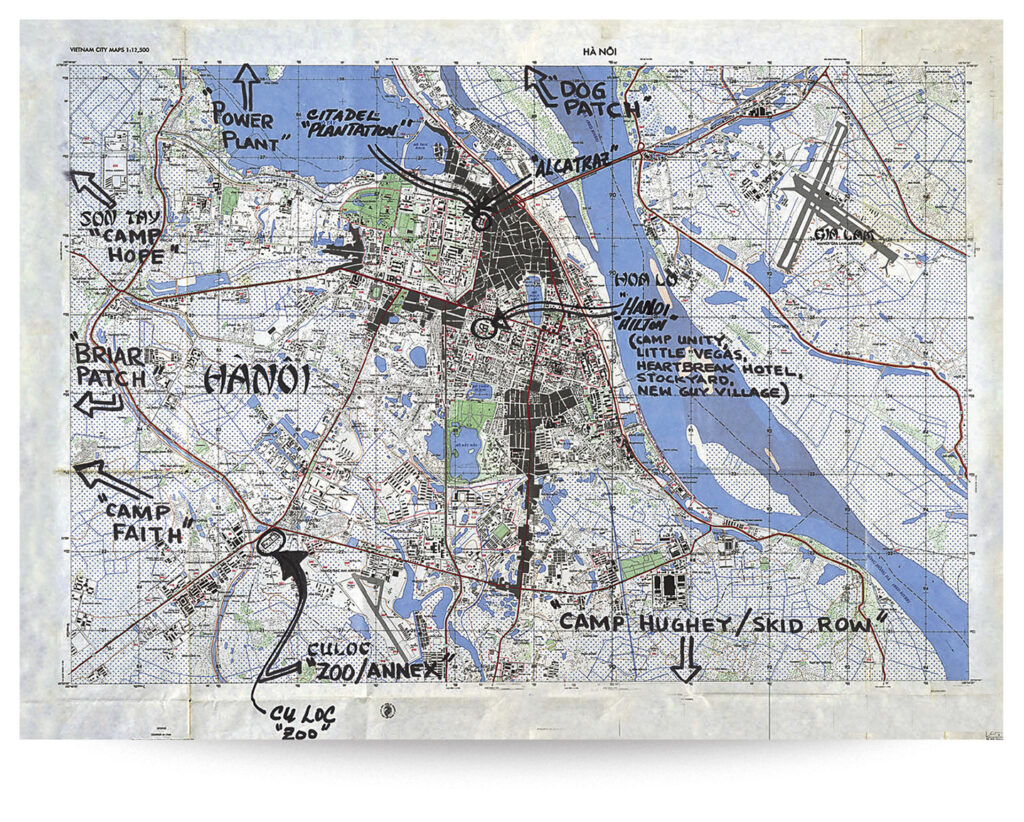

The SR-71s had flown through the world’s most densely defended air space to deliver a message from America’s National Command Authority to a group of U.S. prisoners-of-war (POWs) held inside North Vietnam’s Hoa Lo Prison, better known as the “Hanoi Hilton.” The message consisted of two dots for the letter “I” in Morse code, telling them to “initiate” their escape plan. Thus began the final stages of Operations Diamond and Thunderhead, the Vietnam War’s last POW escape and rescue plan.

The United States had attempted POW rescues before, with the Son Tay Raid of Nov. 21, 1970, being the best known. But Operation Thunderhead was different. This time the plan originated within the POW camp itself. The primary authors of the plan were Captains John Dramesi and George C. McKnight of the U.S. Air Force and then-Lt. j.g. George T. Coker of the U.S. Navy. The men called their escape plan Operation Diamond.

All three had attempted to escape before, only to be recaptured within 36 hours. Coker and McKnight had escaped from a POW compound northwest of Hanoi in 1967, while Dramesi had made two previous attempts, the second one from the Hanoi Hilton. He had been moved there following his first escape attempt from a camp farther up the Red River. The men suffered weeks of torture as punishment for their actions. In fact, Dramesi’s partner in his second breakout, USAF Capt. Edwin L. Atterberry, died on May 18, 1969, ostensibly from an infection while under torture just eight days after their recapture.

The Escape Plan

Undaunted, Dramesi refused to give up on escape. One challenge he faced was opposition from the majority of his fellow POWs. The prisoners had heard Dramesi’s and Atterberry’s screams as the guards beat them, and they knew that their comrades had managed to gain only a few hours of freedom. The POWs would not betray Dramesi but a standing order from the Senior Ranking Officer (SRO) in the Hilton’s “Unity” compound, Lt. Col. Robinson “Robbie” Risner of the U.S. Air Force, required that no escape would be attempted without outside assistance. However, Risner approved the formation of a six-man escape planning committee led by Lt. Col. Hervey Stockman. Coker, Dramesi, and McKnight were joined by Maj. James H. Kasler and Capt. “Bud” Day, both USAF.

The POWs started work on their escape plan immediately, gathering all the information they could about guard patterns, the prison layout, and the surrounding community. One of the many things Dramesi had learned from his last attempt was that their “camp” was located a few miles east of the Red River, not north of it as they had believed when they went over the wall on May 8, 1969. Gathering food supplies was a challenge since the Vietnamese provided little to the prisoners, leaving little to spare.

The greatest impediment to progress was the constant shuffling of the prisoners and senior officers. Day, Stockman, and Risner were transferred out of Unity by December 1970. Risner’s replacement as SRO came in from the “Zoo,” another section of the Hanoi Hilton, where he had vehemently opposed any attempt to escape. He and several others had been tortured and beaten after Dramesi’s last escape attempt. Although Risner had allowed the planning to go forward, the new SRO kept changing conditions and requirements for his approval. Despite his skeptical response, the team continued planning with August 1971 as the “launch date.”

To stand out less after their escape, the three prisoners developed a dye to darken their skin and made civilian-looking clothing by knitting and hand-sewing threads from the blankets and sweaters the guards provided, and by scrounging rags and other discarded materials from around the compound. They also made a map of the compound and surrounding area, along with a compass and simple time piece. All the materials except a tactical radio were ready by June.

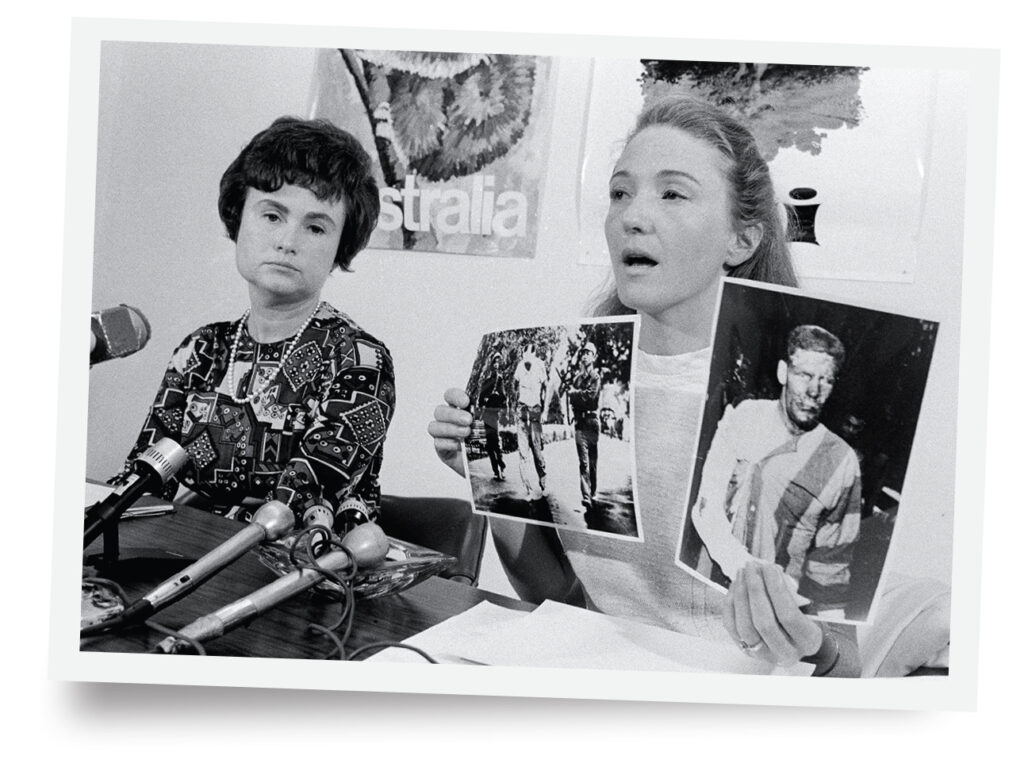

League of Wives

However, the SRO rejected their plan, stating the escape had to have a 90% probability of success as well as approval from higher up in the chain of command. Communicating their plan to higher U.S. authorities seemed impossible. Letters were allowed out on an almost random basis and the prison authorities reviewed them closely. Prisoners were punished severely if the “censors” found anything suspicious in the letters.

Nonetheless, one of the committee members took the chance and incorporated a carefully worded message in a letter home. The League of Wives of Vietnam Prisoners of War delivered it to Secretary of Defense Melvin Laird in late February/early March 1972. The details were slim by necessity but the letter stated a group of POWs were going to escape from the Hanoi Hilton in June 1972 by stealing a boat and making their way to the Gulf of Tonkin via the Red River. It sought official U.S. approval and support of their plan. The number of POWs was not mentioned and the tentative dates were the first two weeks of June. It also wasn’t made clear if the stolen craft would signal with a yellow or red flag. It wasn’t much information to go on and little is known about whom Laird contacted first. However, it is clear that he had either delegated the authorization decision to Adm. Thomas Moorer, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs, by March 31, 1972, or ordered him to launch the rescue.

Moorer wanted to move the planning outside of Washington, D.C. He was very concerned about leaks, which had become a major problem over the previous two years. He directed that all early communications were by courier or face-to-face meetings. Neither known nor suspected leakers were informed. Moorer sent an intelligence officer, Lt. Cdr. Earle Smith, to inform Commander-in-Chief of the Pacific Fleet Adm. Bernard Clarey at his headquarters in Pearl Harbor and Vice Adm. James Holloway, Commander of the 7th Fleet, aboard his flagship the USS Oklahoma City (CLG 5) in Yokosuka, Japan. Lt. Cdr. Edwin L. Towers was appointed officer-in-charge of Operation Thunderhead and given 48 hours to develop the plan.

Enter Special Forces

The forces Towers was given included the nuclear-powered cruiser USS Long Beach (CGN-9), the Frigate USS Harold E. Holt (FF-1074), and Det 110 HC-7, a Combat Search and Rescue Detachment from the USS Midway (CVA-41). Its SH-3 helicopters had infrared sensors, precision navigation systems, and carried a 7.62mm minigun and two M-60 machine guns. Towers knew he needed Special Forces and a means of delivering them. Operations security remained paramount.

The cover story given to the ships’ captains and helicopter detachment commander was that they would be recovering North Vietnamese defectors. Seventh Fleet planned to launch air strikes and naval gunfire attacks on coastal radar stations and sites to draw Hanoi’s attention. Moorer classified the operation as “top secret” and all communications had the added “special category” caveat to further restrict distribution. Only those directly involved in Operation Thunderhead were given access to the reports.

The SEALS’ Mission

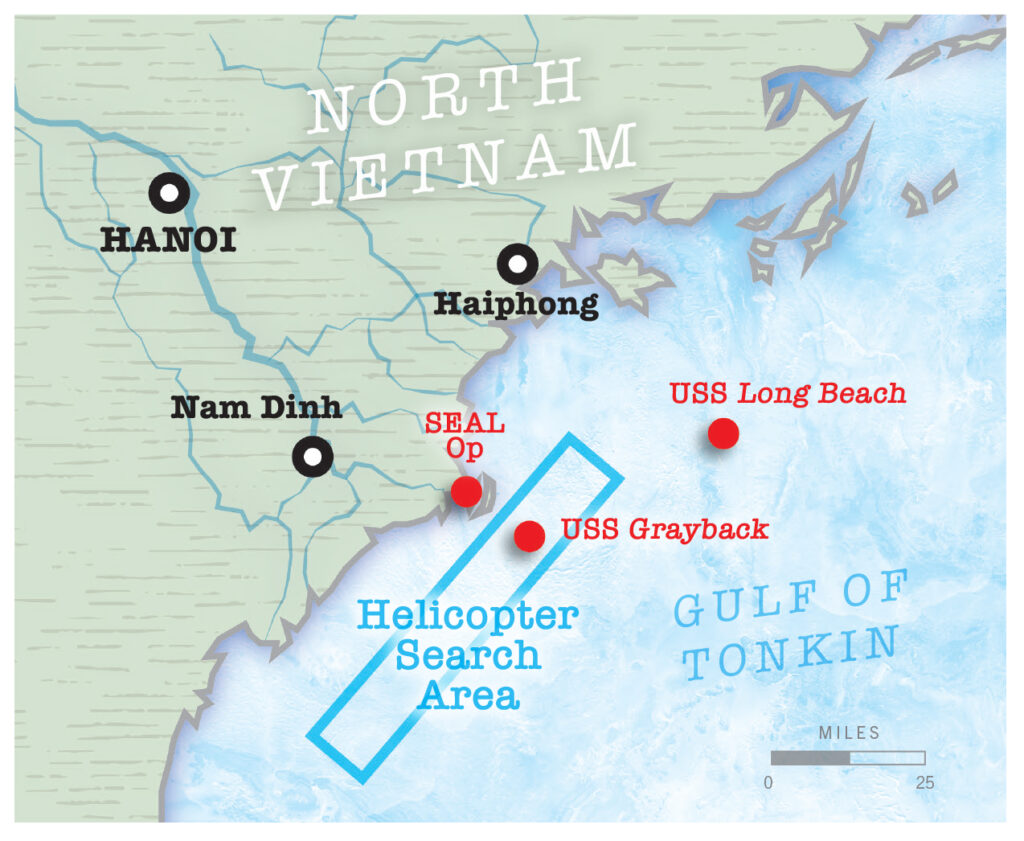

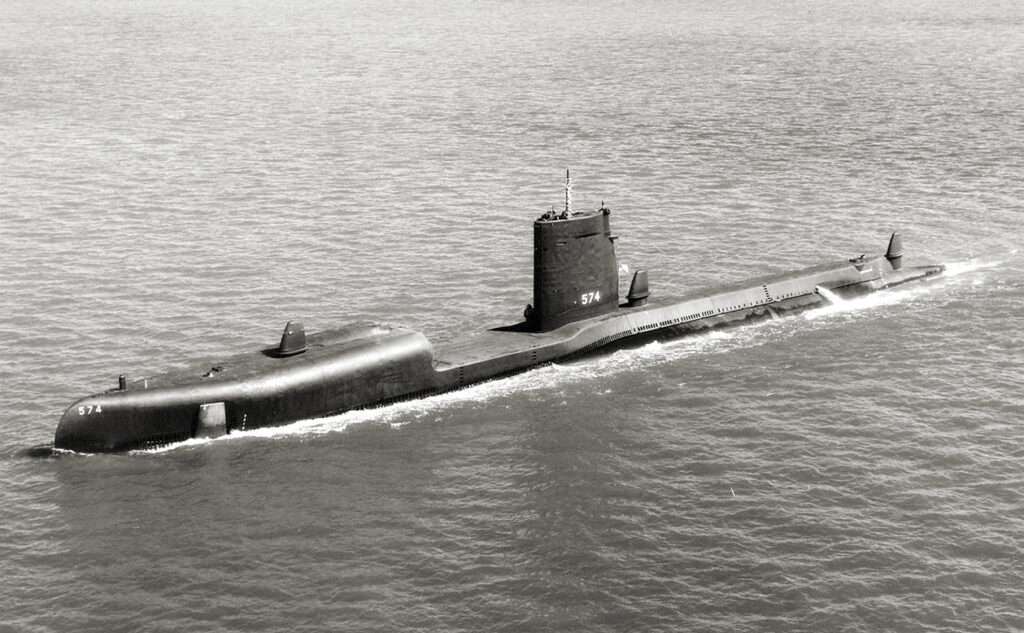

Towers had little to go on but was aware of SEAL Team 1’s Alpha platoon stationed at White Beach, Okinawa, and the USS Grayback’s (APSS/LPSS-574) involvement in special operations. The Grayback picked up a squad from Alpha platoon on April 10 and transported them to Subic Bay in the Philippines by the 13th. Towers flew there to brief the submarine’s skipper, Cdr. John Chamberlain, USN, and then the SEALs and Underwater Demolition Team (UDT) led by Lt. Melvin Spencer “Spence” Dry and Lt. jg. John Lutz, respectively.

Towers told the skipper, UDT, and SEAL leaders that the coming mission was to attack the North Vietnamese radar site that had directed coastal artillery fire against the guided missile destroyer USS Buchanan (DDG-14) earlier that month. The SEALs were to go ashore in Z-birds (high speed inflatable boats powered by an outboard engine).

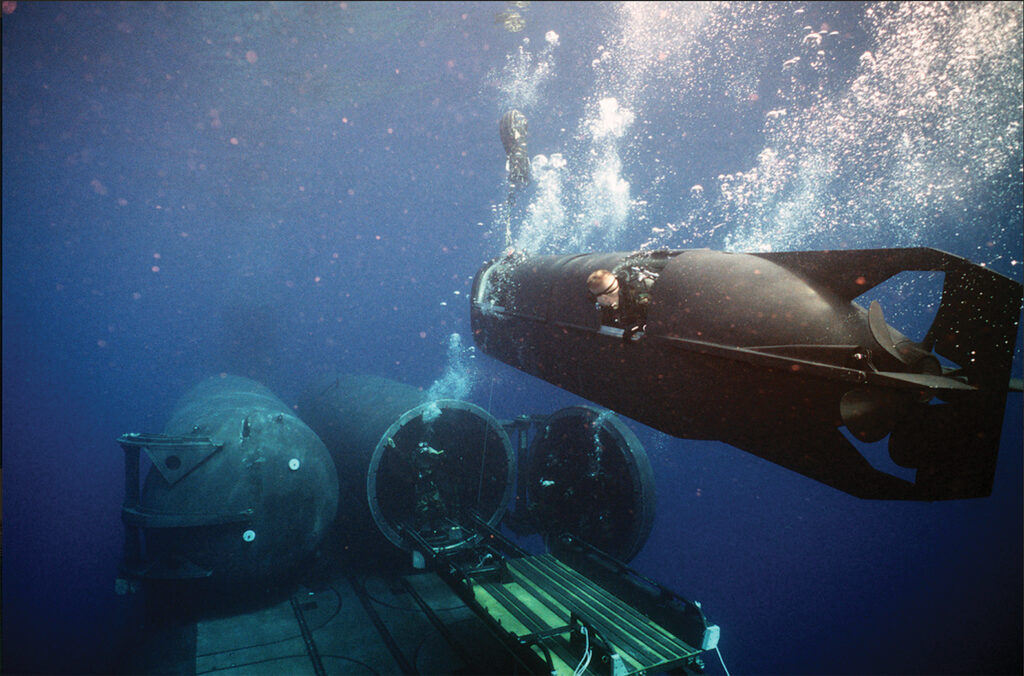

UDT Detachment 11 (UDT 11) was not included in the early briefings, being told only they “might be needed.” The UDT trained on the “new” Mark VII Mod 6 Swimmer Delivery Vehicles (SDVs), or “Six Boats,” while the SEALs conducted night infiltration, demolition, and small unit tactics. The 2-ton SDVs required two UDT operators and carried two fully equipped SEALs or UDT personnel for delivery. The submersibles were roomier than the earlier models and had an onboard air supply the crew and passengers would use while in transit to their release area.

Pleased with the progress, Towers notified 7th Fleet they would be ready in time and departed for Yokosuka. There he briefed Holloway. Towers was to embark on the Long Beach and take station 50 nautical miles off the North Vietnamese coast by May 19. He was ordered to transmit a daily top secret SPECAT situation report to the Commander Seventh Fleet, Commander-in-Chief Pacific Fleet, and the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs. HC-7’s Det 110 began its surveillance patrols off the Red River Delta on May 19, and would continue them until June 19.

To North Vietnam

The Grayback departed Subic 18 days after the SR-71s delivered their first “midnight message.” Once at sea, the SEALs and UDT personnel were told the direct-action mission was a ruse. Their “real mission” was to rendezvous with North Vietnamese defectors and protect them until they could be picked up by helicopter. The SDVs were to deliver two SEALs to an island in the Red River mouth to monitor for small craft carrying a red or yellow flag. A second team was to be inserted two days later and the first team withdrawn back to the Grayback.

The SEALs were to use their best judgment in identifying the defectors’ craft. Once they had the “defectors in hand” they were to signal Towers for helicopter pick up. They were not told the real mission even though they were at sea with no outside contact. The embarked intelligence officer had been told that if a SEAL was captured, there was a risk any un-rescued POWs would be executed or “worse.”

The SEALs adjusted accordingly. Dry walked his people and the UDT personnel through the plan as the submarine made its way to station. They worked daily and watched a lot of movies but Dry was not certain about the intelligence material. The SEALs had operated in the area and were familiar with the tide and currents at and near the surface. This would be their first time using SDVs and other than a brief walk-through in Subic, his people had never used them. He trusted the UDT operators but he would have liked to have trained with them before the submarine got underway.

Meanwhile, POWs Dramesi, Coker, and Mc-Knight finalized plans for their escape. They expected heavy rains in June and noticed power outages often accompanied the storms. They would wait for power failure and then move to the river and either swim or steal a boat as the situation required. The Red River in that area consisted of a complex series of tributaries, streams, and dikes. The three men intended to follow the right branch of any fork in the river that they encountered to reduce the SEALs’ search area. They found little enthusiasm among their fellow prisoners, but no direct opposition. Whatever the other POWs thought about the escape, they would do nothing to impede it. Communicating was a challenge with the North Vietnamese watching almost their every move. Also, the Vietnamese often moved the senior officers around to complicate communication efforts. The guards hoped they were inhibiting the American leaders’ ability to command their subordinates in the camp. The SRO in Dramesi’s cell block rejected the plan in late May but offered to take it to the next most senior SRO. That meeting took several days to arrange.

Trouble Underwater

As the escape team awaited a final decision, the Grayback stalked silently beneath the Seventh Fleet and arrived on station about four nautical miles from the Red River mouth late in the evening on June 3. The sub settled on the bottom of the Gulf in approximately 80 feet of water. Later that evening, Dry decided to conduct a reconnaissance of the island. Departing the Grayback at 2 a.m., he and newly promoted Warrant Officer Philip L. “Moki” Martin boarded the “Six Boat” piloted by Lt. jg. John Lutz and Petty Officer 1st Class Thomas Edwards.

They had launched at “slack tide,” the period between the end of waters receding from low tide and the beginning of high tide. The intention was to have the incoming tide negate the river current. However, North Vietnam’s heavy rains and the minus tide—a low tide much lower than normal—had combined to create a nearly 4 knot current. The SDVs maximum speed was five knots. Making less than 50 yards a minute, the SDV’s batteries burned out more than 1,000 yards from shore.

Recognizing that the currents rendered the plan impractical, Dry decided to contact Towers for helicopter pick up. He transmitted “Briarpatch Tango,” the code words for Thunderhead personnel in trouble. Towers immediately sent an SH-3. Dry needed to return to the Grayback and inform the skipper and his team of the current. Dry and Martin helped the UDT swim the SDV farther out to scuttle it in deeper water but they lacked the means to do. Towers dispatched a helicopter from the Long Beach that sank the SDV with a minigun and returned the four men to the cruiser.

They had no way to contact the Grayback until the scheduled broadcast time later that evening. Dry briefed Towers and the captain of the Long Beach on what he had discovered. Towers agreed that they needed to get word to the Grayback right away. Unfortunately, communications technology of the time limited their options. It would take nearly a day.

That day passed with Grayback being unaware of Dry’s difficulties. Dry’s Deputy Lt. Robert Conger went ahead with the plan, embarking on an SDV for the island. After he departed, the Grayback received a signal that Dry needed to return to the submarine. Chamberlain moved away from the launch point and agreed to rendezvous the helicopter using an infrared spotlight mounted on the submarine’s periscope.

Tragedy for the SEALs

Dry and Martin briefed the helicopter crew on the “casting procedure” by which they would land in the water and descend onto the submarine operating at periscope depth. Martin emphasized to them that they had to descend below 20 feet and that the combined helicopter and wind speed had to be 20 knots or less. The pilots had never done anything like it before. The wind and seas were higher than normal as well and the sky was overcast. Visibility was almost nil.

Shortly after the helicopter departed Long Beach, Grayback sent an emergency message reporting that a North Vietnamese patrol boat had departed base and was en route to the rendezvous area. Chamberlain ordered the cruiser to abort the delivery. It wasn’t received in time. The helicopter reached the rendezvous area and all onboard struggled to find the Grayback’s beacon. Night-vision equipment was bulky and proved nearly useless but the cockpit crew tried their best.

Twice, the helicopter dipped its tail into the sea, nearly swamping. Neither pilot could spot the infrared beacon. Martin couldn’t see the prop wash that would signal they were low enough to drop. Twice the helicopter approached a red light, only to discover it was a Vietnamese fishing boat. The pilots were getting antsy. They were flying less than six nautical miles offshore, well within North Vietnamese waters. Fuel was running low. The pilot was running out of options. If he didn’t find the sub beacon within the next few minutes, he would have to abort and return to Long Beach.

Then, spotting what they thought was the Grayback’s infrared light, the helicopter crew turned towards it and lowered to drop the four men. Unfortunately, the pilot gave the drop signal when the helicopter was above 20 feet and being pushed by a 20-knot tailwind. Dry was killed on impact with the water. Edwards and Lutz were seriously injured. Martin was uninjured but shaken.

A nautical mile away, the second SDV had malfunctioned. It wouldn’t go forward and wouldn’t surface. So Lt. jgs. Conger and Tom McGrath, Petty Officer Sam Birky, and Seaman Steve McConnell had to abandon it submerged and swim to the surface. It was their infrared distress light that the helicopter had spotted, placing Dry and the others close by. Conger, McGrath, and McConnell encountered Martin and Lutz at about 4 a.m. They were less than 2,000 yards from shore and could hear what they believed were North Vietnamese patrol boats in the distance. Dry’s body floated by at around 5 a.m. but Birky was still missing.

Conger was able to contact the Long Beach shortly before sunrise and a helicopter arrived shortly after 7 a.m. It found and picked up Birky along the way. The crews of both SDVs were returned to Long Beach. Dry, Edwards, and Lutz were evacuated to the USS Kitty Hawk (CVA-63), which had a morgue and better medical facilities.

Lessons Learned

The Grayback’s crew knew something had gone wrong with the SDVs but had no information on what or why. The intelligence officer called the senior remaining SEAL, Petty Officer First Class Rick Hetzell, to the wardroom (the officer eating and meeting area). He ordered him to gather a team and prepare for surface insertion using the submarine’s Z-bird. He also wanted him to use the silenced outboard to ensure a covert insertion and tried to put one of the submarine’s Chief Petty Officers in charge of the mission. The “discussion” went back and forth but the chief finally realized he was not value added and opted out.

Upon learning the rescue team survivors were aboard Long Beach, Chamberlain offered to transfer them by Z-bird. He and the SEALs hoped to continue the mission but Typhoon Ora intervened. The Grayback returned to Subic transiting on the surface to save time, only to be engaged briefly by USS Harold E. Holt, whose crew mistook her for an unidentified hostile contact. The helicopters continued their searches until June 19 without ever spotting any POWs in stolen boats.

The Thunderhead team didn’t know it, but the SRO had ordered Dramesi and his mates to stand down. He felt the war was coming to an end and he didn’t want the POWs to suffer the physical abuse and potential fatalities that might follow an escape attempt, even if it succeeded. Operation Homecoming finally started bringing the POWs home on February 13, 1973.

Lt. Melvin S. Dry was the last American SEAL to die in the Vietnam War. Because of its highly classified and compartmentalized nature, Operation Thunderhead remained all but unknown and its participants unrecognized until 2008. Dry was posthumously awarded the Bronze Star with a V for Valor while Moki Martin received the Navy-Marine Corps Medal with a V for Valor. It was America’s last POW rescue attempt and it would have failed even if the SEALs had made it ashore successfully, since the POWs never escaped from the Hanoi Hilton. Despite that, the mission reflected America’s national commitment to bringing “everyone home.”

A thorough investigation followed and most of its lessons learned resonate to this day. Towers did an outstanding job in the planning and execution of Operation Thunderhead but excessive secrecy, the justification for which ended when the Grayback left port, reduced if not eliminated his ability to modify plans in the face of equipment and operational setbacks. The transport delivering Special Operations Forces (SOF) needed to be integral to the SOF unit to ensure mutual familiarity and commitment. The helicopter pilots did their best but were conducting a sensitive and dangerous evolution for the first time in their careers and under very difficult circumstances in enemy territorial waters.

Also, hopefully leaders now recognize that prisoners in remote undeveloped countries have little capability to escape on their own. It is best to go to them once they are located. And there were the equipment failures as well. The Mark VII SDVs shortcomings were addressed by the introduction of the Mark VIII SEAL Delivery Vehicles in 1982.

Capt. Carl O. Schuster, U.S. Navy (Ret.), is a career naval officer who served on many U.S. and allied warships before serving at U.S. Pacific Command’s Joint Intelligence Center. He serves on the advisory board of Vietnam magazine.

This story appeared in the 2024 Winter issue of Vietnam magazine.

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.