In World War II, thousands of Japanese American soldiers served their country as translators in the Pacific Theater. Bruce Henderson’s new book examines this little-known story about the Nisei—first-generation Americans born of Japanese parents—who fought against their ancestral homeland. Bridge to the Sun: The Secret Role of the Japanese Americans Who Fought in the Pacific in World War II details the experiences of some of these soldiers. Henderson, a New York Times bestselling author of several histories about World War II, talked with World War II about the book.

Why did you decide to write this book?

I came to it in a serendipitous way. I was researching my last book on the Ritchie Boys—Sons and Soldiers: The Untold Story of the Jews Who Escaped the Nazis and Returned with the U.S. Army to Fight Hitler—and I came across information about the Japanese Americans who fought in Europe. I knew about that. But then I read there were several thousand Japanese American soldiers who trained for the Pacific Theater. I’ve written World War II books and I didn’t know that. I figured most people probably didn’t know it, either.

I circled back when I finished the Ritchie Boys and found that there were strong parallels between them. Both were trained in secret for identical missions, only in opposite theaters of war. And each endured their own brand of prejudice and distrust. Many of the Ritchie Boys were Jewish Germans with accents. Of course, the Nisei and their families were rounded up and put in camps because they were not trusted. Both had to overcome those barriers to become valuable assets for the U.S. military. They knew the language, culture, and customs of our country’s enemies better than anyone and could gather valuable intelligence.

In your book, you focus on a select cadre of soldiers. Why?

I tell a bigger story through the lives of a few. I want readers to get to know these men. I want readers to know what they’re thinking, feeling, and fearing. I feature the Kibei, who are Nisei educated in Japan. It was not uncommon then for immigrant parents to send their sons back to the homeland. These boys were as American as anybody. But when the war broke out with Japan, our government didn’t trust them as ethnic Japanese. Over 60 percent of folks in the internment camps were American citizens. Then, four or five months into the war, the army realizes they need this language skill in the Pacific.

Many Nisei raised by immigrant parents could speak a little Japanese but were not fluent in reading and writing. However, the Kibei were. Suddenly they went from being the most distrusted to being the most desired by the army. Even though they’re in the internment camps, the great majority of these young men were ready to prove their loyalty.

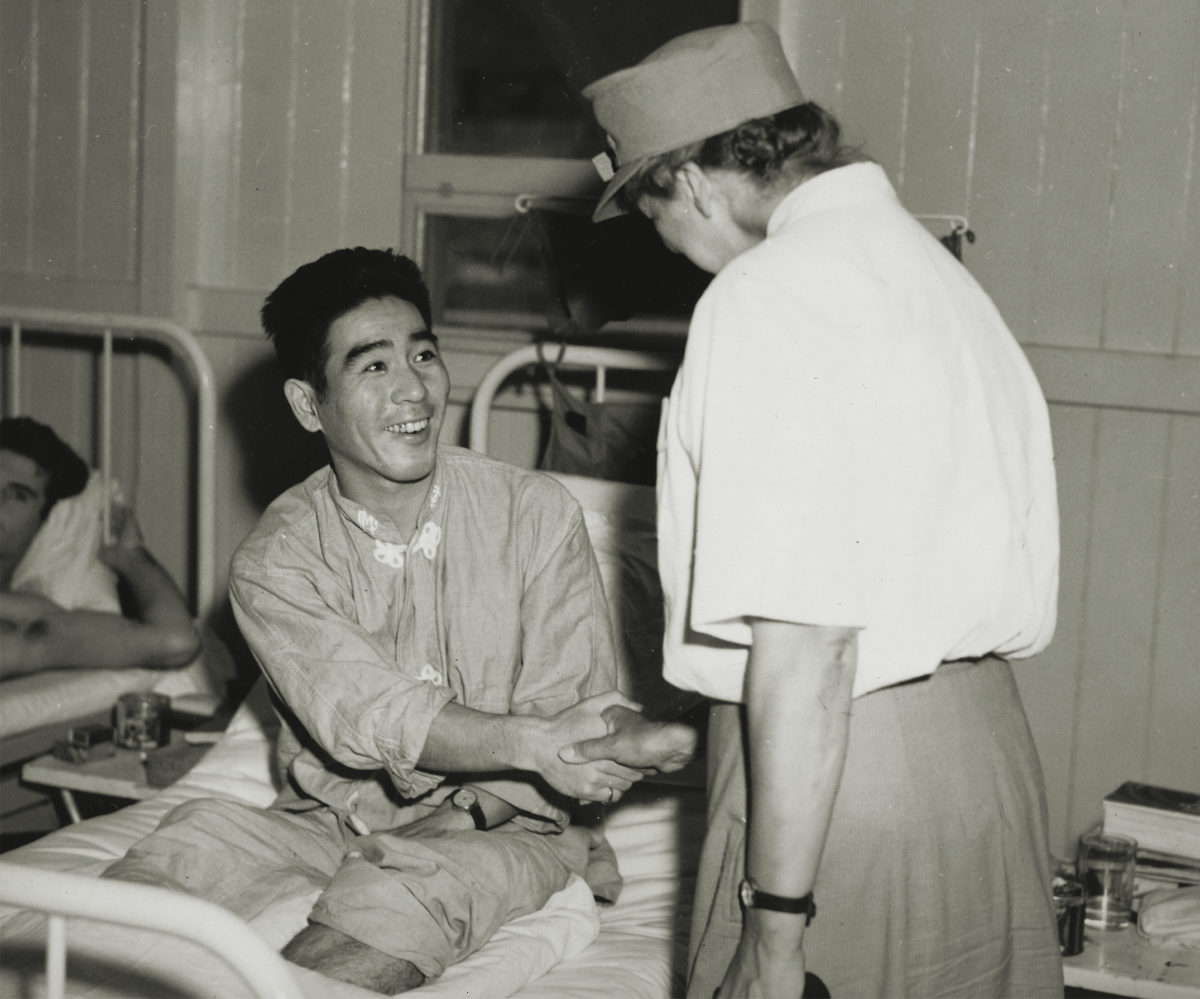

Kazuo Komoto was the first Nisei wounded in the war. He was shot in the knee in July 1943 at New Georgia Island in the Solomons and ends up in his hospital in Fiji. Who comes by his bed? Eleanor Roosevelt! We actually found a picture of that moment. He told the president’s wife how unfair it was that his family was behind barbed wire while he was being shot at. Later, he admitted to feeling guilty about challenging the president’s wife but, by God, he wanted to let her know how he felt.

What kind of bigotry did these men have to endure?

Komoto was still recovering when he left the hospital, so he went to visit his family in Arizona. He stopped at a store because he heard the interned didn’t have fresh meat. The butcher looks at him and says, “I don’t sell to Japs.” Komoto, who is in his uniform with his ribbons, answers, “I’m not a Jap. I’m an American.” The butcher looked him over said, “Well, what do you want?” Here is this guy who’s fighting for his country and this is what he faces his first time back.

That’s why I thought it was time for this story. We’re in a country where anti-immigrant sentiments are still prevalent. Too often, America still prejudges based on race, ethnicity, country of origin. Bridge to the Sun is a timeless message of what true patriotism is all about.

Why don’t we know this story?

For starters, it was highly secret during the war. We didn’t want the Japanese to know we had teams in the Pacific with these skills. The Japanese were arrogant about their language. They felt Westerners, even if they could hold a conversation, weren’t going to be able to read or write it. In Burma, Roy Matsumoto of Merrill’s Marauders climbed up a tree and listened on a telephone line as Japanese soldiers spoke without using a code. They are at an ammunition dump and Roy figures out the coordinates so they can destroy it. That’s why it was so secret.

There weren’t a whole lot of men who served over there. Only about 4,000 made it to the Pacific, compared to something like 20,000 Japanese Americans who fought in Europe. They served in small 10- to 12-man teams, so there wasn’t a lot of camaraderie like the bigger units. After the war, they got busy living their lives, going to school, working, raising families. They just didn’t talk about it. Some families tell me they didn’t realize the stuff their dads did. It wasn’t something these men freely shared.

Considering what the Nisei experienced, where did their fighting spirit come from?

These guys had several motivations. There was anger because they went from being 1A to 4C for the draft, meaning they couldn’t serve at first. They were not good enough to defend their country. They also wanted out of the detention camps. They wanted to win the war in the Pacific so they could get their families out of the camps.

All they wanted to do was serve their country. One Japanese mother told her Nisei son, “This is America. It’s your country. It’s not my country, nor your father’s country. You must defend it and make us proud.” Those boys went to war with that message ringing in their ears.

Tell us more about Roy Matsumoto.

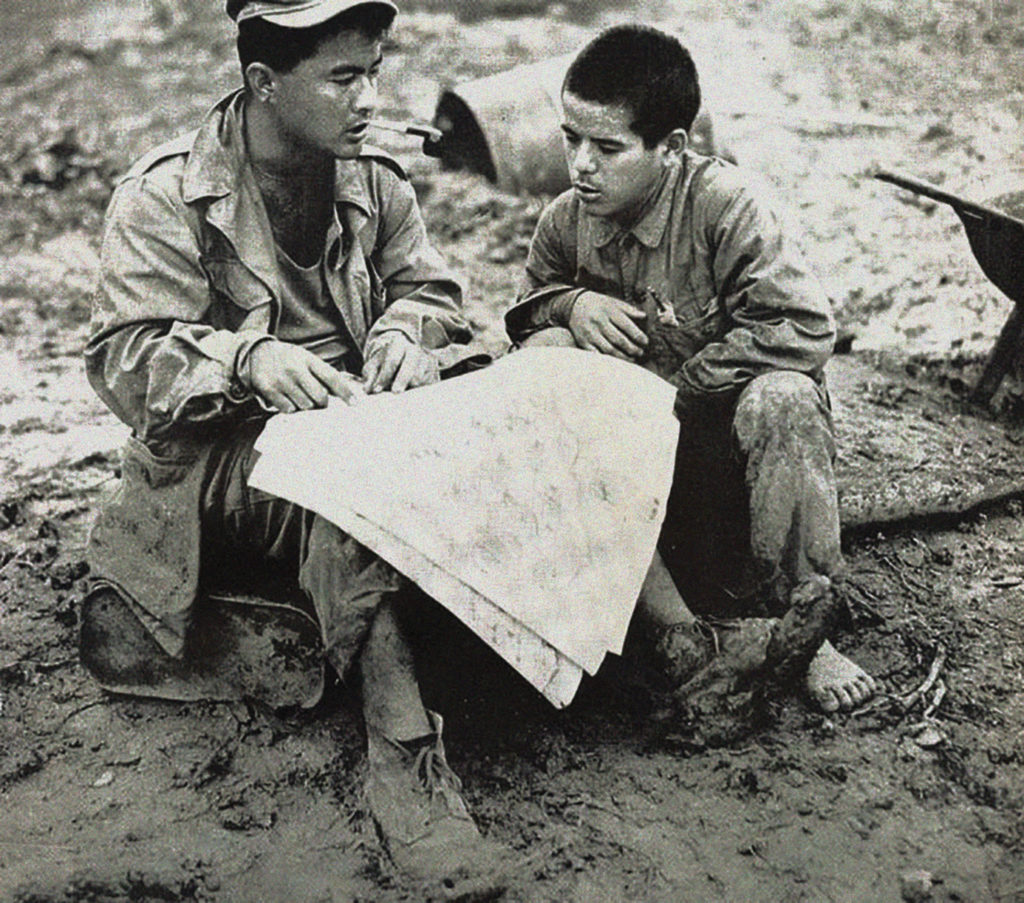

Roy was born in California and went to school in Japan. He was ready to come home when his parents moved back to Japan, so he lived there with them. Roy went back to America and was living in L.A. with his sister when the war broke out. He was highly agitated when he found out he could not join the army. Then he and other Japanese Americans were rounded up and sent to a camp in Arizona. Recruiters were looking for these fellows who could speak, read, and write Japanese. Roy signed up and went to Camp Savage [U.S. Military Intelligence’s language school in Minnesota]. Then he volunteered for Merrill’s Marauders. He was one of 12 with that team. They were translators but they were in combat in Burma, fighting alongside the riflemen. Roy became a true hero when his battalion was surrounded on a mountaintop and were in danger of being overrun. At night, he crawled through the brush and got close enough where he hears Japanese soldiers talking about the next day’s battle. Before heading out, Roy leaves his helmet and gun behind and takes two hand grenades with him. His lieutenant asked him why. Roy said, “One is for them and one is for me.”

Roy comes back and tells his superiors where the Japanese are going to attack. The Americans rig the area with explosives and set up fields of fire. When the first wave attacked, the Japanese were mowed down. The second wave hesitated when they saw all the dead bodies. Roy stood up and yelled in Japanese, “Charge, charge, charge!” The second wave was annihilated, too. Something like 60 or 70 Japanese soldiers were killed but not a single American died. When Merrill’s Marauders started having reunions, Roy was always honored as the hero of the Second Battalion for what he did that day in Burma.

Who are some of the other heroes?

Takejiro Higa was born in Hawaii to Okinawan parents. He was taken to Okinawa when he was 2, staying until he was 17. Then he joined his sister in Hawaii, finishing school there. When he was recruited, Higa’s biggest fear was that he might have to fight on Okinawa. All of these guys felt that way. Matsumoto had three brothers in Japan and he worried he was going to see them on the other side of the battleline. Would they have done their duty? Of course, but can you imagine what they went through?

Higa went with a team in a division that was preparing for the invasion of Okinawa. Once he gets to the island, he does everything he can to help civilians. He never fired his rifle. He went to the caves to convince the Okinawans not to kill themselves. They had been brainwashed into believing the Americans were going to torture them and figured it was better to die with their family in a cave. Higa convinced them not to. He went from one cave to the next, always saying the same thing: “I’m Okinawan, but I am in the U.S. Army. We will care for you. We will feed you.” Fifty years later, he went back to Okinawa and met someone he had talked out of a cave. That guy thanked him. At that moment, Higa really felt that he had done his duty for America by saving lives on Okinawa.

Tom Sakamoto is an amazing guy. I joke he was my Forrest Gump because he was everywhere, including on the USS Missouri when the Japanese surrendered. He was the first Nisei officer to go into Hiroshima after the bombing, escorting Western correspondents.

Then you have people like Grant Hirabayashi and his cousin Gordon. They grew up together and each makes a totally opposite choice when the war breaks out. Grant joins the army and serves with Merrill’s Marauders. At the same time, Gordon protests the treatment of Japanese Americans, refuses to register for the draft, and is arrested. His case goes to the Supreme Court. Yet both men respect the decision made by the other. Grant, a true war hero, does not think any less of his cousin for the choice he made.

What do you want readers to take away from the book?

It’s a dramatic and inspirational story at a time when it’s sorely needed in this country. Japanese Americans with ancestral ties to a nation we were at war with were distrusted. But they stepped forward as Americans and became huge assets to our military because they knew the enemy better than anyone. They were highly motivated to see America win the war.

With the anti-immigrant sentiment in this country today, we need to be reminded that we all came from somewhere. We prejudge way too often on the basis of race, ethnicity, and countries of origin. For me, that’s the takeaway. I just shake my head in awe when I think about what these men accomplished.