The Untold Story of the Jews Who Escaped the Nazis and Returned with the U.S. Army to Fight Hitler

By Bruce Henderson. 448pp. William Morrow, 2017. $28.99.

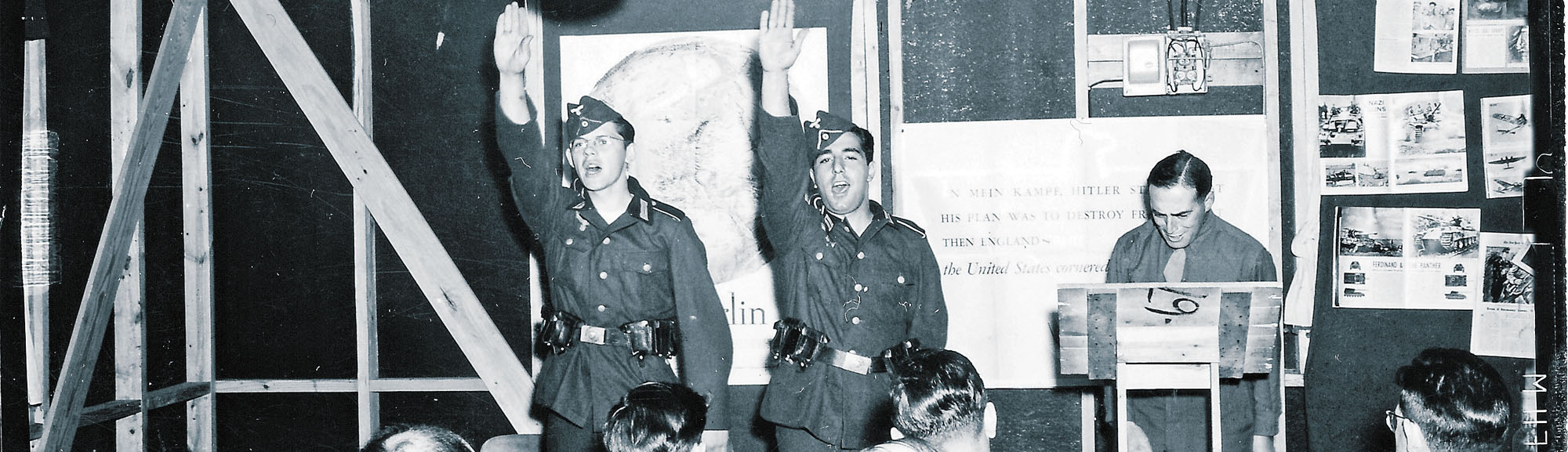

AFTER WORLD WAR II, the U.S. Army carried out a study called “The Military Intelligence Service in the European Theater of Operations.” The dry-sounding report revealed the efficacy of specialists who were trained at Camp Ritchie in Maryland and concluded that they were “extremely valuable to all commands to which they were attached.” Some of the most remarkable of the intelligence specialists known as the Ritchie Boys were the 1,985 German-born Jewish soldiers who had trained at the camp. These men played a key role in returning to their former homeland to take the fight directly to the Nazis.

In Sons and Soldiers, Bruce Henderson gives an impressive account of these men. Using research gathered through numerous interviews with surviving veterans as well as archival information, Henderson expertly delineates the lives and valor of the Ritchie Boys, from growing up in Germany to battling Nazis.

War planners in the Pentagon quickly realized that German-born Jews already in American uniform could form a crack force. The Ritchie Boys were attached to frontline units, parachuting in on D-Day and racing with General George S. Patton’s tanks across Europe. According to Henderson, they “took part in every major battle and campaign of the war in Europe, collecting valuable tactical intelligence about enemy strength, troop movements, and defensive positions as well as enemy morale.” After the war, they interrogated tens of thousands of former Third Reich soldiers.

As Jews, the Ritchie Boys faced an extra set of dangers while battling the Nazis: not only did they risk being killed by their former compatriots in battle, but also, if captured, they would face certain execution. As a result, Henderson notes that many Ritchie Boys altered their German or Jewish names before heading overseas and were careful to destroy “clues to their past such as addresses, photographs, and letters, which could not be found on them should they become POWs.” Indeed, they did not speak to each other in German.

However, even when the Ritchie Boys conquered those dangers, the effects of war never left them. When the men triumphantly returned to Germany as liberators, the experience of witnessing the hellish aftermath of the concentration camps proved traumatizing to many. Take, for example, Guy Stern, whose parents had shipped him off to the United States in 1937 to live with his aunt. Stern had always hoped he would see his family again, but what “he saw at Buchenwald ripped at his heart and took away what hope remained,” Henderson writes. Several years later Stern would learn that his family had perished at the Treblinka concentration camp.

That horror, among other reasons, drove the men to see that justice was done after the war. Henderson recounts their effort to ensure that one German officer who had ordered the murder of two Ritchie Boys ended up being executed by firing squad in June 1945.

In all, Sons and Soldiers is filled with gripping stories that carry us into a greater understanding of how the Ritchie Boys risked much to confront the evils of the Third Reich. —Jacob Heilbrunn is editor of the foreign policy magazine the National Interest, and author of They Knew They Were Right: The Rise of the Neocons (2008).