President Franklin D. Roosevelt famously declared Japan’s December 7, 1941, bombing of Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, “a date that will live in infamy.” For those of Japanese ancestry in America, the date even more deeply seared into memory is February 19, 1942. That day, Roosevelt ordered the mass removal from the West Coast of “all persons deemed a threat to national security.” In practice, Order 9066 applied exclusively to American Japanese, 120,000 of them. Of those ordered from their homes, 70 percent were American citizens.

Wholesale evacuation took months to gestate but arrests began immediately after Pearl Harbor. Using newly compiled lists of “suspect enemy aliens,” the FBI detained 1,000 German and Italian immigrants and 1,200 prominent Japanese Americans. The latter were nearly all male, most living on the West Coast or in the U.S. territory of Hawaii.

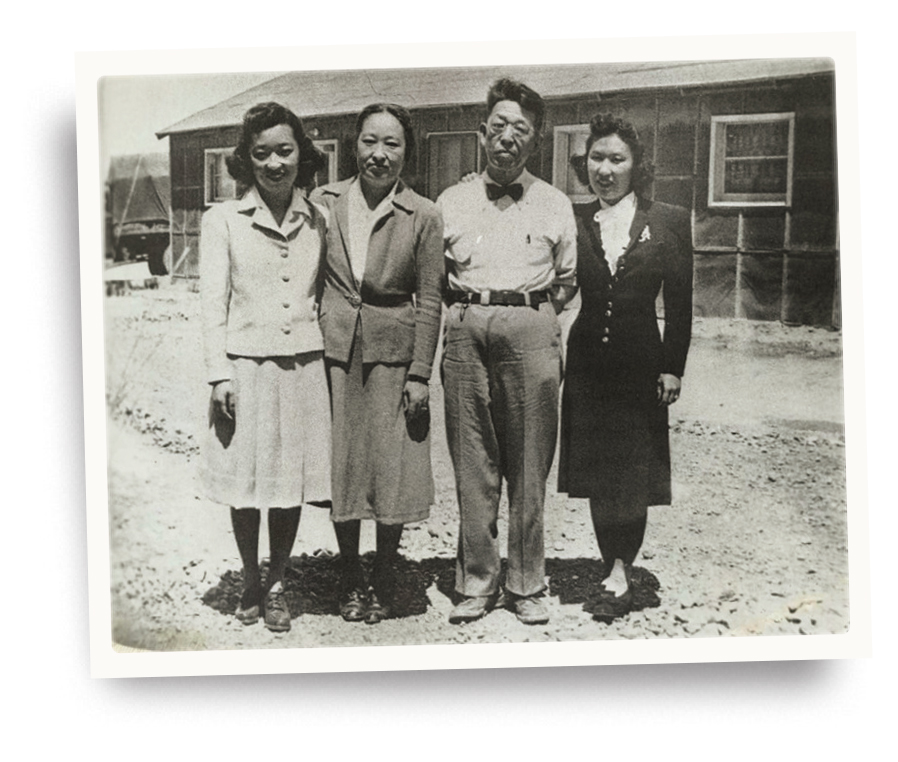

UC Berkeley student Yoshiko Uchida returned from the campus library that December 7 to find an FBI agent searching her parents’ Berkeley home, demanding to know the whereabouts of Yoshiko’s father, an executive with a Japanese-owned export firm. Dwight Uchida was soon arrested and confined with other suspects at the Presidio army base before being sent to a federal prison in Missoula, Montana.

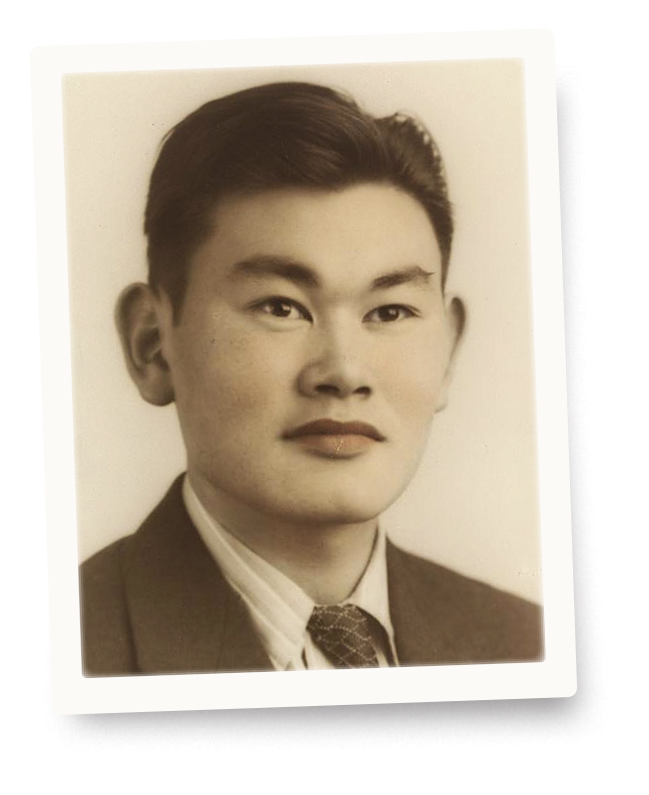

After ransacking Japanese farmers’ homes in Oregon’s Hood River Valley, FBI agents arrested community leaders, including Tomeshichi Akiyama, president of a local cultural group, the Japanese Society. Akiyama’s son George was among 3,000 Nisei, or second-generation Japanese Americans, then serving in the U.S. military. Some Nisei in uniform were peremptorily discharged; in addition, the Selective Service stopped accepting Japanese Americans who were trying to enlist. Once the services realized the utility of having Japanese speakers in the ranks and the need for trained combat personnel, officialdom shipped most Nisei servicemen inland to Minnesota and Wisconsin for intelligence training and readiness drills.

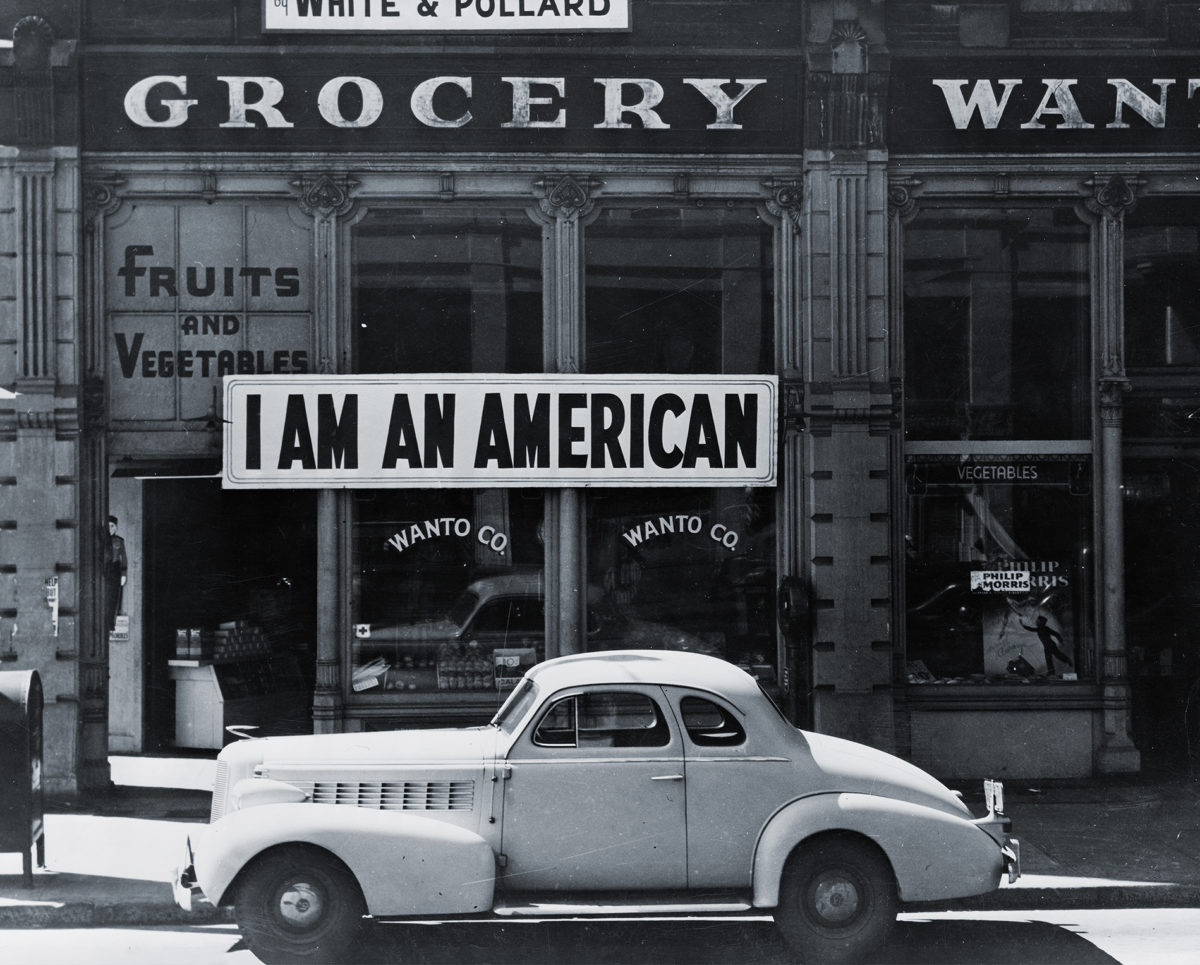

Japanese Americans pushed back. The president of the vigorously patriotic Japanese American Citizens League, Saburo Kido, telegraphed FDR: “We are ready and prepared to extend every effort to repel this invasion together with our fellow Americans.”

Rafu Shimpo, the largest stateside Japanese-language newspaper, editorialized in English that Japan had started the war and America must end it: “Fellow Americans, give us a chance to do our share.”

White American animus toward Japanese immigrants was nothing new. Naturalization laws enacted in 1790 and 1894 denied Japanese U.S. citizenship. Increasing numbers of Japanese immigrant farmers motivated a 1913 California ballot measure proscribing Japanese ownership of land. Even though Japan had stood with the Allies during World War I, the 1924 Johnson-Reed Act cut off all immigration from Japan.

The Depression and Japan’s 1936 alliance with Germany and Italy intensified suspicions in America of Japanese aliens, as well as of non-citizens of German and Italian ancestry. FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover already had presidential approval for secret domestic intelligence-gathering. After Germany invaded Poland on September 1, 1939, Hoover directed every FBI field office to document individuals who during wartime “would constitute a menace to the public peace and safety of the United States Government,” especially those warranting detention. The “ABC list” rated leaders of ethnic organizations as As; many Cs simply supported cultural societies.

The Alien Enemies Act of 1918 allowed detention of non-citizens deemed dangerous—a step explicitly reserved for wartime. As Americans nervously watched fighting erupt in Asia and Europe, Congress buttressed Hoover’s secret work. The Alien Registration Act of June 1940 ordered all non-citizens photographed and fingerprinted. By January 1941, almost five million individuals had registered nationwide, including 90,000 Japanese. Hoover publicly stoked fear, warning of fifth-column intrigues by “the vilifying Communist and the espouser of alien philosophies.” The Justice Department, trying to rein in Hoover, divvied up responsibilities for a potential roundup and detention campaign with the War Department.

Between December 7, 1941, and mid-March 1942, FBI agents arrested 6,700 “alien enemies.” Detainees included several hundred operatives implicated in a Japanese spy circle run out of that nation’s consulate in Los Angeles; those arrested were deported. A dozen members of a German American Bund chapter were exonerated of charges that they provided privileged defense information to the Axis. Most of those charged in the weeks after Pearl Harbor were guilty only of their ancestry.

An eventual sweeping program of evacuation and internment rolled up only American Japanese. Besides being Caucasian, German and Italian immigrants and their descendants were too familiar, too numerous, and too strongly supported by fellow citizens. No one wanted Joe DiMaggio’s mother arrested. Only when authorities had hard evidence did they move against individuals of European ancestry. But distrust of Japanese in general was pronounced and deep-seated.

By early 1942, California politicians were aligning with the Elks, Townsend Clubs, and other grass-roots groups demanding swift action against Japanese living on the West Coast. California Attorney General Earl Warren had first counseled moderation; now he was invoking a “repetition of Pearl Harbor.” Governor Culbert Olson, eyeing Warren as a November 1942 election opponent, told Congress, “I believe in the wholesale evacuation of the Japanese people.” Los Angeles Mayor Fletcher Bowron fired all city workers of Japanese descent.

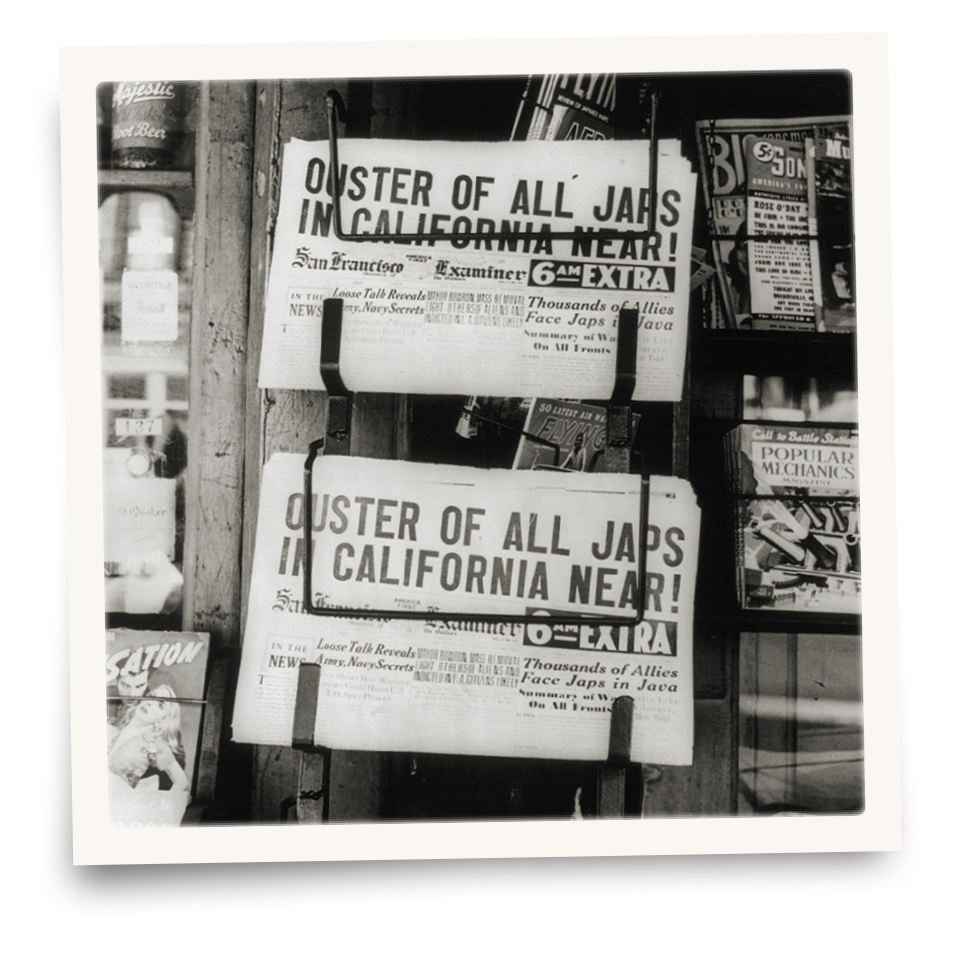

Newspapers large and small had long fueled anti-Japanese prejudice. The San Francisco Chronicle accused Japanese in Hawaii of aiding the Pearl Harbor attack. Sacramento Bee editors insisted, “The possibility of a Japanese attack on the coast has loomed ever larger.” Radio pundit John B. Hughes claimed 99 percent of the Japanese in America would “die joyously for the honor of Japan.” Speaking in Pullman, Washington, CBS correspondent Edward R. Murrow remarked, “I think it’s probable that, if Seattle ever does get bombed, you will be able to look up and see some University of Washington sweaters on the boys doing the bombing.”

In Washington, DC, some power brokers doubted the need for a forced relocation. Eleanor Roosevelt publicly warned against “foolish prejudices about other races.” She privately urged her husband and other officials to counter the prevailing winds. Attorney General Francis Biddle and other Justice Department higher-ups argued against removal of Japanese Americans. Even the rabid Hoover agreed. “The necessity for mass evacuation is based primarily upon public and political pressure,” the FBI chief wrote in February 1942.

The most knowledgeable military officials agreed. Lieutenant Commander Kenneth Ringle, a naval intelligence officer who had served in the American embassy in Tokyo and later on western naval bases, spoke Japanese; his extensive network exposed the Japanese consulate spy ring. Ringle said he felt that “the entire ‘Japanese Problem’ has been magnified . . . largely because of the physical characteristics of the people.” Army deputy chief of staff General Mark Clark, who had long served in Hawaii, thought evacuation unnecessary.

The situation looked different to the Army’s head of Western Command. From his headquarters at the Presidio in San Francisco, Lieutenant General John DeWitt argued for removal. “Racial affinities are not severed by migration,” Dewitt wrote the secretary of war. “The Japanese race is an enemy race.” DeWitt’s office repeatedly issued alerts of non-existent raids and attacks. In a recommendation to the president DeWitt nonsensically declared, “The very fact that no sabotage has taken place to date is a disturbing and confirming indication that such action will be taken.”

Ultimately, the decision rested with the commander-in-chief. Urged on by Secretary of War Henry Stimson, FDR signed Executive Order 9066 on February 19, 1942. Attorney General Biddle reckoned that the president was either unduly swayed by hysteria or simply chose expedience. Roosevelt got the politics right: a national poll found that more than 90 percent of respondents endorsed evacuation of Issei—Japanese-born immigrants. Seventy-five percent also favored removal of Nisei—children of Issei, American citizens by birthright.

(Mark Kauffman/Getty Images)

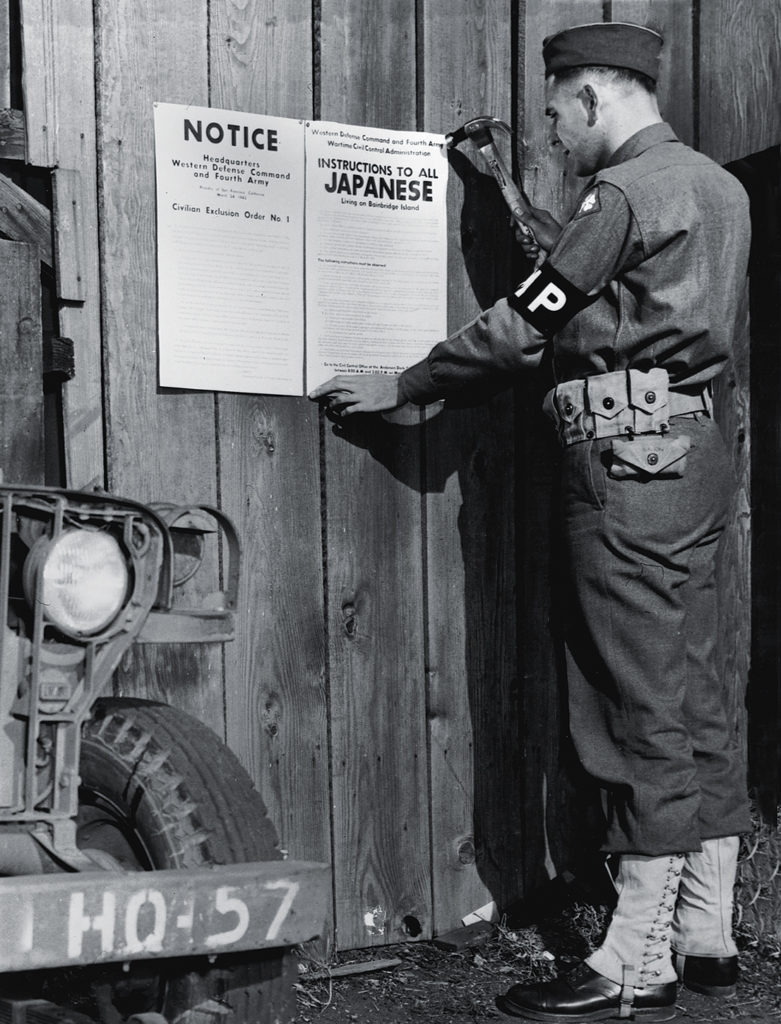

An exclusion zone was quickly defined and a War Relocation Authority (WRA) organized to coordinate mass removal to “relocation centers.” Any person of 1/16th or more Japanese ancestry was to register for evacuation. The exclusion zone encompassed Western Washington and Oregon, California, and southern Arizona—the region where most Japanese in America lived. The other large concentration was on Hawaii, where a blanket expulsion of Japanese residents would devastate the economy. Only Hawaiian residents of Japanese descent on one of the FBI’s lists were detained.

The army issued orders to evacuate by area, beginning March 24. The 300 Issei and Nisei who lived on Bainbridge Island off Seattle got six days’ notice. They could take only what they could carry. Farmers abandoned crops, college students walked away from campuses, owners frantically negotiated sales of businesses and residences. A fortunate few had friends or neighbors willing to store cherished possessions or adopt small businesses. No one knew whether their area of the exclusion zone would be next. “What had I, or . . . what had the rest of us done, to be thrown in camp, away from familiar surroundings and familiar faces?” a Nisei wondered. “It is your contribution to the war effort,” the official reply went. “You should be glad to make the sacrifice to prove your loyalty.”

The federal government was by no means prepared to house more than 100,000 people. Thousands on the ABC lists were already jailed at military bases and other facilities. To house displaced Issei and Nisei while more permanent facilities were being built outside the exclusion zone, 17 temporary “assembly centers” were designated. In California racetracks, fairgrounds, and camps were rapidly repurposed.

George Takei was five when his family was sent to Santa Anita Racetrack. “Each family was assigned a horse stall still pungent with the stink of manure,” he later wrote. Young Takei thought it fun to sleep where horses had slept. He didn’t mind the semi-private stalls and communal showers and lavatories. His parents, who had been forced to give up a prosperous dry-cleaning business, were devastated.

Yoshiko Uchida, with her mother and sister, ended up at Tanforan Racetrack near San Francisco, housed in a stable. The utter lack of privacy mortified many women. “I felt degraded, humiliated, and overwhelmed,” Uchida later wrote. “And I saw the unutterable sadness on my mother’s face.” The family spent five months at Tanforan; in time Dwight Uchida, now an “enemy alien on parole,” joined them.

Identifying ten sites for relocation camps proved difficult. “The Japs live like rats, breed like rats,” spit Idaho Governor Chase Clark. He and counterparts in Wyoming and Arizona decried the use of their states as “dumping grounds.” Japanese victories in the Pacific worsened hysteria despite an utter lack of evidence that Japanese Americans were committing sabotage. The WRA eventually won approval for remote internment sites under strict guard, as at a prisoner-of-war camp. Manzanar and Tule Lake in eastern California became the best known, but there were also camps in Idaho, Wyoming, Utah, and Colorado, plus two each in Arizona and Arkansas.

From May through November 1942, thousands of Japanese American families were transported, mostly by trains with window shades drawn, to the hastily constructed camps. The internees arrived under heavy military guard at dusty, bare, and arid sites. Of the camp at Poston, Arizona, a San Diegan said, “No trees, no flowers, no birds singing, not even the sound of an insect.” Arriving at the desolate Topaz, Utah, site, Yoshiko Uchida saw greeters “standing in the burning sun, covered with dust.” Most facilities had been placed amid dust bowls or swamps that made efforts at cleanliness exasperating.

Rolls of barbed wire, watch towers, and armed sentries guarded blocks of pine and tar paper barracks. The quarters lacked plumbing and privacy. Toilets and showers were communal. Each family was assigned a room ranging in area from 8’x20’ to 20’x20’; couples and individuals shared the smaller spaces with strangers. Everyone received a straw mattress and army blanket. One conscientious objector helping evacuees settle in made a point of remaining outside while a family entered. “It was too terrible to witness the pain in people’s faces, too shameful for them to be seen in this degrading situation,” he said.

Many internees endured their situation with little complaint, murmuring “Shikata ga nai,” “It cannot be helped.” Dwight Uchida spent his first morning at Topaz helping clean latrines. Food poisoning raged for lack of refrigeration. Yoshiko Uchida volunteered to help organize housing assignments until she could apply for a camp job.

As the relocation centers became organized, block councils became the most effective self-governing apparatus, though their success varied by camp. The council for each 250-to-300 resident group of barracks included a block manager, elected representatives, and the head chef for the block. Male Nisei and bilingual Issei like George Takei’s father Norman became block managers, who tried to meet the needs of block residents. Block managers and councils took direction from and negotiated with the Caucasian camp staff, helped establish schools, worship spaces, and playing fields. They guided the creation of health clinics and barber shops, as well as community newspapers and gardens. Hiroshi Kashiwagi, a block manager at Tule Lake, felt he had “little or no voice” and was simply a flunky of camp administrators. Norman Takei and others fared better.

Living conditions at the camps reshaped lives and relationships. For instance, block organization undercut family structure. Amid the buzz and clatter of mess hall dining, parents were frustrated in their efforts to teach manners and values during meals; teens often began eating with peers. At Manzanar, Jeanne Wakatsuki’s family, “after three years of mess hall living, collapsed as an integrated unit.” Block council decision-making also stole some parental authority. On the other hand, young people craving more independence found it with peer groups or by securing jobs or college admission away from camp.

Tensions were evident from the first. Each camp’s population of about 10,000 threw together Issei and Nisei, country folk and city dwellers, Buddhists and Christians, bilingual speakers and those who knew little English. “Internal squabbling spread like a disease,” wrote Yoshiko Uchida. Shoddy healthcare meant actual sickness ran rampant. Jobs paid little and erratically at that. The minority of Issei hoping Japan would win resented Norman Takei and fellow American patriots as inu—”dogs,” meaning collaborators. Many Nisei wondered bitterly what American citizenship was worth. Some, particularly the Kibei—Nisei educated in Japan—joined camp gangs.

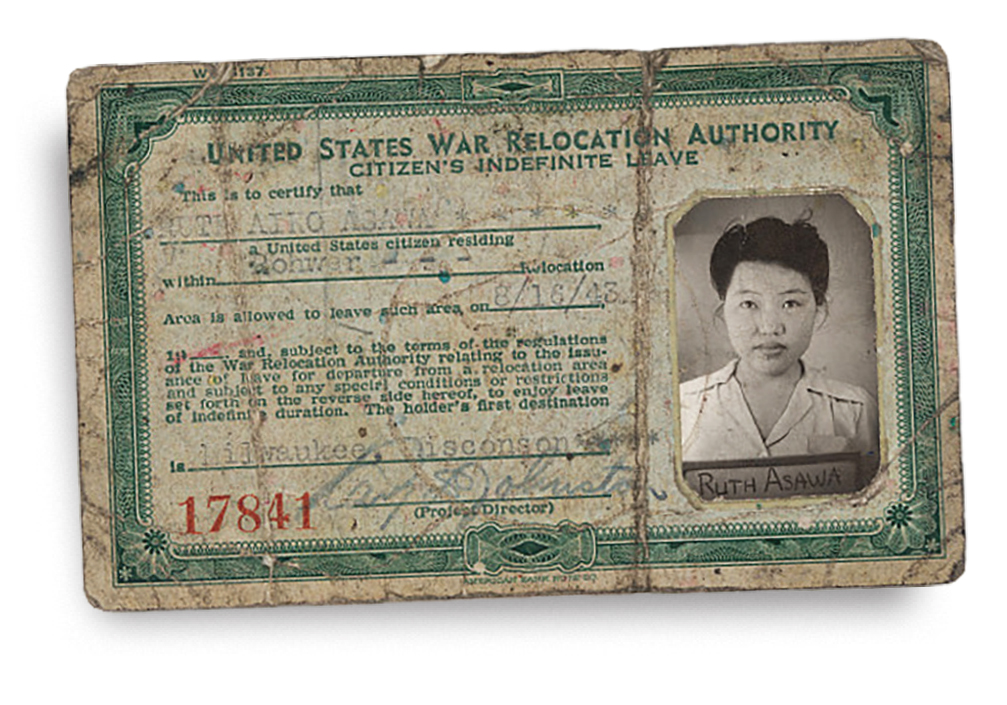

In the fall of 1942, WRA director Dillon Myer toured the barely settled relocation centers to talk about resettlement. Myer had quickly realized that internment “saps the initiative, weakens the instincts of human dignity and freedom, creates, doubts, misgivings and tensions.” Recognizing camp staff and resident concerns as well as labor shortages nationwide, he launched an expansive leave policy. Internees with health issues could apply for short-term leaves. College students could depart camp indefinitely if a midwestern or eastern university accepted them. Yoshiko Uchida soon left Topaz for graduate study at Smith College only to be assailed on the train by a conductor barking, “You’d better not be a Jap!” Despite continuing prejudice, by 1945, 4,300 Nisei had entered or resumed college. “Work leave” allowed internees to work at nearby farms or businesses, earning far more than camp wages. At Minidoka, Idaho, 2,000 internees left to work the fall 1942 harvest. The other Uchida sister, Keiko, left Topaz to take a teaching job in the East.

By 1943, Secretary of War Stimson had convinced FDR to allow Nisei internees to serve in the army. Lieutenant General DeWitt still believed “a Jap is a Jap,” and opinion polls suggested that the American public mostly agreed. Nevertheless, Stimson, WRA staff, and others working with detainees increasingly supported not only resettlement but drafting Nisei. The tailored enlistment process soon morphed into a questionnaire given all internees to answer. Two questions read:

27.

Are you willing to serve in the armed forces of the United States on combat duty or wherever ordered?

28.

Will you swear unqualified allegiance to the USA and faithfully defend the U.S. from any and all attacks by foreign or domestic forces, and forswear any form of allegiance to the Japanese emperor, to any other foreign government power or organization?

Question 27 presumed that a draft-age man should serve a country that had destroyed his and his family’s lives. Question 28 implied that all Japanese in America worshipped the emperor. And Issei who renounced Japanese citizenship would be stateless.

The two questions outraged internees and exacerbated tensions between Nisei and Issei.

Mitsuo Usui, at the Granada, Colorado, camp, told his parents he wanted to enlist. “We lose everything—the property, the business, our home!” his father shouted. “Now they’re saying come in and shine my shoes!” He kicked Mitsuo out. Some Issei reminded their sons that their own World War I service had failed to gain them citizenship. The fact that the army planned to segregate Japanese American soldiers was no help.

Bureaucrats rewrote Question 28 to be less inflammatory, but grievances remained; 3,000 internees delayed answering by requesting repatriation to Japan. Among those completing the form, nearly 90 percent answered yes to both questions.

Egged on by the U.S. Senate, Lt. General DeWitt, and now-Governor Earl Warren, WRA director Myer moved to separate “loyals” from “disloyals,” though there were still multiple reasons for people’s answers or refusal to answer. For example, knowing that “disloyals” were to be transferred to the Tule Lake, California, camp, 40 percent of original camp residents there, among them George Takei’s parents, answered no-no in order to remain at Tule Lake and avoid further disruption.

During the summer of 1943, the 12,000 internees who either refused to answer or answered “no” to both loyalty questions were transferred to Tule Lake and held under maximum security. A circuit court judge later described the conditions as worse than those in a federal penitentiary. Within a couple months of the transfers, Tule Lake workers went on strike. A few weeks later, hundreds of internees staged a protest around the building where WRA Director Dillon Myer was visiting, demanding better food and worker pay. During the same period, internees suspected of cooperation with camp officials were often beaten by pro-Japan gangs. Martial law was declared, during which hundreds were imprisoned in the camp stockade. Several thousand “no-no’s” at Tule Lake were eventually exchanged for American prisoners of the Japanese.

The no-no turmoil meant that efforts at military recruitment in the camps largely failed. About 1,200 Nisei volunteered from all ten camps. By contrast, Hawaii enlistment offices were swamped with non-interned Hawaiian Nisei. Thousands eventually served in the Army, half of those from Hawaii; 800 lost their lives.

From a high of about 120,000, the interned Japanese American population was down to 90,000 when FDR proclaimed an end to the evacuation in January 1945. Roughly half of those interned never returned to the West Coast, choosing to settle in the Midwest or elsewhere, among them Yoshiko Uchida and her sister. Death claimed 1,900 internees. George Takei’s impoverished family returned to Los Angeles, living first on Skid Row and later in the East L.A. barrio. George grew up to be an actor.

Survivors of internment fought for redress. In 1948, the Japanese Americans Evacuation Claims Act designated $100 million to compensate for lost income and property, distributing $37 million to 26,550 claimants. American citizenship was opened to Japanese immigrants beginning in 1952. In 1980, a federal Commission on Wartime Relocation included one former Tule Lake internee, William Marutani. The Commission estimated losses at $1-2 billion (in 1980 dollars). Three years later, the Commission recommended a formal apology, educational efforts, and reparations of $20,000 each.

After vigorous lobbying by 100-plus survivors, Congress passed the Civil Liberties Act of 1988, affirming that during 1941-45 Japanese Americans had been incarcerated “without adequate security reasons and without any acts of espionage or sabotage.” Internment was “motivated largely by racial prejudice, wartime hysteria, and a failure of political leadership.” Initially reluctant, President Ronald Reagan signed the bill on August 10, 1988. Some 82,000 internees lived to see the moment.

Key Case: Korematsu v. United States

The U.S. Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of internment on December 18, 1944. Dissenting Justice Robert Jackson called the ruling a “legalization of racism.” On that same day, the Supreme Court ruled in Ex parte Endo that the WRA lacked the authority to detain “concededly loyal” citizens; the ruling steered clear of constitutional issues, but was seen as nudging FDR’s announcement of the end of internment. In 1983, Korematsu was overturned, based on proof that the federal government had suppressed evidence that the Japanese in America posed no military threat. (SCOTUS 101, August 2019)

This article appeared in the Winter 2023 issue of American History magazine.

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.